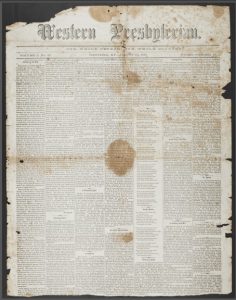

During the early to middle decades of the nineteenth century there was likely not an issue of a western Presbyterian periodical that did not have at least one mention of the name, “Breckinridge.” The August 10, 1865 issue of the Western Presbyterian, shown in the picture, provides a good example of the many occurrences of the name.

During the early to middle decades of the nineteenth century there was likely not an issue of a western Presbyterian periodical that did not have at least one mention of the name, “Breckinridge.” The August 10, 1865 issue of the Western Presbyterian, shown in the picture, provides a good example of the many occurrences of the name.

A considerable portion of the issue was taken up with articles that were in some way related to the recent end of the Civil War. Not only was the often struggling Danville Theological Seminary in Kentucky faced with increased financial difficulties due to the post-war economy, but it also had to fill two faculty positions, one of which had been vacated by R. J. Breckinridge. Despite tight purse strings the seminary’s associate and more stable institution in Danville, Centre College, managed to purchase an advertisement in the Western Presbyterian listing its faculty and its president, W. L. Breckinridge. W. L. Breckinridge appears once again in another article, “Church Property in the South,” which purposed to set the record straight regarding the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America and its relationship to the Southern congregations that had left their assembly in 1861. The relevant resolution was presented as follows.

That this General Assembly direct the Board of Domestic Missions to take prompt and effectual measures to reclaim the Presbyterian churches in the Southern States of the Union, by the appointment and support of prudent and devoted Missionaries.

Breckinridge’s name appeared as one opposing “all interference with the property belonging to the Southern people.” After debate and amendments that included changing the word “churches” to “congregations,” the resolution was adopted with part of it reading as amended, “to take prompt and effectual measures to restore and build up the Presbyterian congregations in the Southern States….” The word “churches” had been understood by some, including W. L. Breckinridge, to mean the property and not the people. Breckinridge opposed all interference with the property belonging to the Southern people. It is distressing as one reads Presbyterian history to see how many times presbyteries, synods, and assemblies became involved in debates, court cases, splits, and feuds over their physical property. The time that was used could have been better spent by officers and members to pursue their primary work as worshippers and workers for the Kingdom, however sometimes conflict must take place for the purity and peach of the church.

In the next two columns on the same page there is a letter from W. L. Breckinridge responding to accusations made against him by R. L. Stanton in regard to a speech of his at the recent General Assembly. Breckinridge’s response is based on some correspondence exchanged through earlier issues of the Western Presbyterian and the subject of the dispute is not clear other than it had to do with the post-war situation and the South. The disagreement may have involved the speech regarding the use of the words churches and congregations. Breckinridge was restrained in his letter, but he was not happy at all with Stanton. It would have been a tense moment for onlookers when the two passed each other on the street, which may have happened often because they are both listed in the assembly minutes directory as residing in Danville.

Thus, the current posts on the homepage of Presbyterians of the Past are all biographies of members of the Breckinridge family. They can be accessed by following the links.

Mary Hopkins (Cabell) Breckinridge, 1769-1858

Robert J. Breckinridge, 1800-1871

William L. Breckinridge, 1803-1876

Samuel M. Breckinridge, 1828-1891

I have found the intricacies and complexities of the Breckinridges interesting. The family has not only had an important place in Presbyterian history, but also in the political and social history of the United States. In these brief biographies, there are three characteristics common among the Breckinridge men—their concern for the church, their defense of confessional doctrine, and their willingness to fight, which in a few cases included not only verbal but physical conflict.

Regading the sources, first, for the source of the image of the Western Presbyterian, see the the end of this article. Secondly, the title of this post is borrowed from Bradley J. Gundlach’s article, “B” Is for Breckinridge: Benjamin B. Warfield, His Maternal Kin, and Princeton Seminary,” in Gary L. W. Johnson’s, B. B. Warfield: Essays in His Life and Thought, P&R, 2007, pages 13-43. Thirdly, one of the most confusing problems faced when reading nineteenth-century church publications is the similarity of periodical names. In the case of Old School publications there is a dissertation that untangles the web of confusion. Peter Wallace’s, “The Bond of Union: The Old School Presbyterian Church and the American Nation, 1837-1861,” Notre Dame, 2004, includes an appendix titled, “Old School Periodicals,” which gives information regarding the years of the periodicals’ runs, the places of publication, the editors, and other information. In the case of the Western Presbyterian, it was first published in Danville, Kentucky, 1865-1866, then Louisville, 1866, and finally Louisville and St. Louis, 1866-1870. The editors for the run included Edward P. Humphrey, Stephen Yerkes, Heman H. Allen, and S. J. Nichols. Over eighty percent of the subscribers were from Kentucky, which prompted Wallace to comment that it might better have been better titled The Kentucky Presbyterian.

Barry Waugh

Sources–The picture of the Western Presbyterian is from the digital collection of the University of Kentucky as accessed through Creative Commons. For information regarding use of the image see, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.