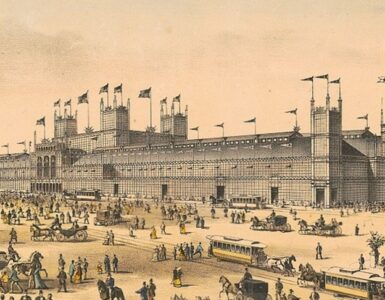

The header image is a drawing of Savannah, Georgia, circa 1870, which was composed by its artist while viewing the city to the south from Hutchinson Island. On the left of the sketch almost in line with the mast near the stern of the ship that has two masts is the faint image of a slender, tiered, and tall structure that is the steeple of Independent Presbyterian Church. Visitors of the era aboard ship entering the harbor from the Atlantic, travelling down the Savannah River from Augusta, or crossing the river from South Carolina would know that at the base of the steeple a church could be found. The steeple continues currently to be visible from various vantage points around and within the city. Independent Church was completely destroyed by fire in 1889 but was reconstructed exactly like the original, so even though the steeple is not the one pictured in the image, it is the same design.

For this article, a “steeple” will be considered to be any structure originally designed for housing and protecting a church bell, which would include simple shelters, cupolas, belfries, spires, and towers. Even though housing a bell is not normally an aspect of their function in newly constructed modern churches, steeples exist today because they were built to house bells.

Steeples are becoming less common for a variety of reasons. They are costly—they are not only expensive to build but they require maintenance and repairs which in days of yore were accomplished by a professional acrophobia-free tradesman called a steeplejack. Another factor working against steeples is if they house a bell or carillon, it is a feature that some communities prohibit because ringing then is considered a nuisance noise. Another reason for the demise of steeples may be that some churches believe investing in a steeple is a poor use of the building fund, which is a reason each church has to consider as it determines how best to use the Lord’s funds.

Steeples and the bells they house are not unique church design elements of Protestant history. Roman Catholic churches had bells that not only called parishioners to mass but were also the means for communicating the occurrence of key events within the parish (remember Quasimodo of Notre Dame). The tolling of the bell for deaths and its ringing for other significant events in the congregation was frowned upon by Protestants due to the Catholic practice of charging a fee for a special ringing of the bell for an event such as a marriage or baptism. It was believed by Protestants that tolling the bell for a funeral would encourage superstition because of its association with Catholicism, but despite a more restrictive view regarding the use of bells, they were still used in the country churches for signaling key events because the church bell was often the news voice of the day.

For the Presbyterians in Scotland, John Knox’s first Buke of Discipline, 1560, specified that a properly fitted church needed “a bell to convocat the people together.” Margo Todd notes that late in the sixteenth century the same bells that “had summoned parishioners to mass before the Reformation were rung three times at half-hour intervals before each sermon.” In the summer the bell rang at 8:30, 9:00, and 9:30 for the service at 9:30, with the same three-ring pattern for the 4:00 afternoon service, but in the winter the three-ring sequence announced the morning service at 10:00 and then they announced the afternoon service at 1:30. The different times in winter were for the shorter period of daylight to allow parishioners from outlying areas to have light for their travel. If a church bell rang six times each Sunday in some modern communities it might raise some protests from their anti-noise citizens.

In Scotland, many bells had been removed from churches during the Reformation because of their association with Roman Catholic practices and there was a shortage of bells. By the seventeenth century, churches were importing their bells from the Low Countries. Belfries had been used on cathedrals, monastic churches, and larger urban churches in the Middle Ages, but in the country churches a more simple gabled structure often protected the bell. Towards the end of the sixteenth century and well into the seventeenth, belfries were often simply constructed with a pyramid-like roof finished off with a finial and sometimes a weathervane.

In Scotland, many bells had been removed from churches during the Reformation because of their association with Roman Catholic practices and there was a shortage of bells. By the seventeenth century, churches were importing their bells from the Low Countries. Belfries had been used on cathedrals, monastic churches, and larger urban churches in the Middle Ages, but in the country churches a more simple gabled structure often protected the bell. Towards the end of the sixteenth century and well into the seventeenth, belfries were often simply constructed with a pyramid-like roof finished off with a finial and sometimes a weathervane.

By the eighteenth century, the design had developed to include arched or rectangular openings for the sound to exit at the sides, a molded cornice, an ogival or double-curved roof design, a finial, and sometimes a weathervane for citizens to view the wind direction. Sometimes the belfry was atop a tower connected to the church, but often they sat like a cupola upon the peak of the roof. Some belfries were constructed on the wall extending above the roof. The city churches of Scotland were fancier and grander due to the greater wealth of their members and they tended towards the greater expense of towers; the country churches were often simpler and used more basic structures due to the limited funds available to their congregations and some churches even had their bells on the roof without shelter.

By the eighteenth century, the design had developed to include arched or rectangular openings for the sound to exit at the sides, a molded cornice, an ogival or double-curved roof design, a finial, and sometimes a weathervane for citizens to view the wind direction. Sometimes the belfry was atop a tower connected to the church, but often they sat like a cupola upon the peak of the roof. Some belfries were constructed on the wall extending above the roof. The city churches of Scotland were fancier and grander due to the greater wealth of their members and they tended towards the greater expense of towers; the country churches were often simpler and used more basic structures due to the limited funds available to their congregations and some churches even had their bells on the roof without shelter.

As the years passed and architectural tastes evolved, the utilitarian design of the early cupola-like bell houses developed into architectural expressions of beauty that not only directed strangers to church doors but pointed the citizens to heaven as they looked to the tip of the spire. Sir Christopher Wren’s more than fifty churches constructed in London following the Great Fire of 1666 influenced church design for generations and towering steeples were a part of his legacy. In urban churches, the city congregations constructed their Episcopal, Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian sanctuaries. It would not have been uncommon to be able to stand on a hill at the edge of a town and see four steeples, each representing one of the four denominations that could trace its history fully or partially to Protestant roots.

Unfortunately, the high price of real estate, the industrialization and commercialization of the nation, the secularization of society, and a failure to grasp the uniqueness of the spiritual ministry of the gospel through the design of a congregation’s physical property have all contributed to the decline of ecclesiastical architecture. Care must always be used to be faithful and judicious stewards of God’s tithes making the best use of the funds available, but through contemplation, care, and consultation with design and construction professionals, the design of a church can still be distinctive in its use of wood, masonry, and aesthetics and say, “This is a church, it is where the gospel is preached, God is worshiped, and Christians are growing in sanctification.”

In conclusion, pictured is a recently completed Presbyterian congregation’s church building. The steeple is a distinctive element of the design and its uniqueness is enhanced by the play of light on its spire. Not only does the steeple signal that it is a church but its illumined entrances provide access for services. The church is located on a prominent hill on the main road where it is visible to visitors and residents entering the business district. Imagine a family on a trip driving into the community for lodging on a Saturday evening and a child in the backseat saying, “Here’s the church; here’s the steeple; open the doors; and there’s all the people,” as hands and fingers are manipulated through the familiar motions associated with the rhyme. The family was able to locate a place to participate in worship on the Lord’s Day and they did it with the help of distinctive church architecture that included a steeple.

Barry Waugh

Sources—The image of circa 1870s Savannah is the author’s. The picture of the church with the illumined steeple was provided by the pastor. Margo Todd, The Culture of Protestantism in Early Modern Scotland, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, pages 29, 340; a thorough, clearly written, and fascinating book. George Hay, The Architecture of Scottish Post-Reformation Churches, 1560-1843, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957, pages 167-168 in particular, but the section of 163-177 covers bells, towers, and steeples. John Knox’s The First Buke of Discipline, 1560, is in, The Works of John Knox; Collected and Edited by David Laing, vol. 2, Edinburgh: The Woodrow Society, 1848, page 252; note that “convocat” in the quote used is the way it is in the original.

Notes—Some congregations that have built churches in recent years have opted for the simpler look of the old country churches of Scotland using masonry, simple windows, and a distinctive door. Maybe a bell in a simple structure could be placed on the roof of such a church even if ringing is not allowed in the community. Just leave the clapper out and lock the bell in place for a more authentic connection to early Presbyterianism. For an interesting picture of a steeplejack who has completed his work on a steeple that is 180 feet high, see, David B. Calhoun, The Glory of the Lord Risen Upon It: First Presbyterian Church, Columbia, South Carolina, 1795-1995, 1994, the picture is in the photo section between pages 237 and 245. The book is available in digital form from the church website at, www.firstprescolumbia.org, but the picture and text quality are better in the hardcopy.