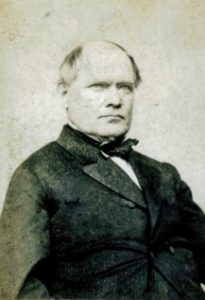

The transcription that follows is the text of a paper originally delivered by Stuart Robinson to the First General Presbyterian Council, which convened in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1877. Robinson had represented the United States churches in the committee that organized the council. Once the council convened, he was the chairman, i.e. moderator, of the morning sessions on Wednesday, July 4, which included papers and addresses by ten presenters under the heading of “Consensus of Reformed Confessions.” Then, that afternoon Dr. W. H. Goold of Edinburgh assumed the chairmanship and a series of papers was presented under the general heading, “Principles of Presbyterianism.” The session opened with Dr. John Cairns of Edinburgh reading his piece titled, “The Principles of Presbyterianism,” then Dr. A. A. Hodge of Princeton Seminary presented his paper with the thought provoking title, “Adaptation of

The transcription that follows is the text of a paper originally delivered by Stuart Robinson to the First General Presbyterian Council, which convened in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1877. Robinson had represented the United States churches in the committee that organized the council. Once the council convened, he was the chairman, i.e. moderator, of the morning sessions on Wednesday, July 4, which included papers and addresses by ten presenters under the heading of “Consensus of Reformed Confessions.” Then, that afternoon Dr. W. H. Goold of Edinburgh assumed the chairmanship and a series of papers was presented under the general heading, “Principles of Presbyterianism.” The session opened with Dr. John Cairns of Edinburgh reading his piece titled, “The Principles of Presbyterianism,” then Dr. A. A. Hodge of Princeton Seminary presented his paper with the thought provoking title, “Adaptation of  Presbyterianism to the Wants and Tendencies of the Day.” Then Stuart Robinson, who had published a book nearly twenty years earlier titled, The Church of God as an Essential Element of the Gospel, showed his continued interest and concern for ecclesiology by reading, “The Churchliness of Calvinism: Presbytery Jure Divino its Logical Outcome.” The last two papers of the afternoon were read by the editor of The New York Observer, Dr. Samuel Irenaeus Prime, whose subject was, “Presbyterianism in the United States of America,” and Dr. James Eells, who had recently become the professor of apologetics and pastoral theology in San Francisco Theological Seminary, read his paper titled, “Presbyterianism as Related to the Tendencies and Wants of our Age.”

Presbyterianism to the Wants and Tendencies of the Day.” Then Stuart Robinson, who had published a book nearly twenty years earlier titled, The Church of God as an Essential Element of the Gospel, showed his continued interest and concern for ecclesiology by reading, “The Churchliness of Calvinism: Presbytery Jure Divino its Logical Outcome.” The last two papers of the afternoon were read by the editor of The New York Observer, Dr. Samuel Irenaeus Prime, whose subject was, “Presbyterianism in the United States of America,” and Dr. James Eells, who had recently become the professor of apologetics and pastoral theology in San Francisco Theological Seminary, read his paper titled, “Presbyterianism as Related to the Tendencies and Wants of our Age.”

The First General Presbyterian Council had originally been scheduled for 1876, but because of the centennial of the United States and its grand exposition in Philadelphia it was decided to postpone the meeting until 1877. It was felt that the centennial celebration would have presented the American commissioners and associates with a difficult decision regarding their allegiances to church and state. Dr. Robinson delivered his paper on July 4, which seems appropriate because his emphasis on elders ruling the church paralleled the republican form of government of his one-hundred-year-old nation. Maybe he had the parallel in mind.

The source for Dr. Robinson’s paper is pages 60-68 of, Report of Proceedings of the First General Presbyterian Council Convened at Edinburgh, July 1877, with Relative Documents Bearing of the Affairs of the Council, and the State of the Presbyterian Churches Throughout the World, which was edited by John Thomson and published in Edinburgh by Thomas and Archibald Constable, Printers to the Queen and the University, 1877. If you would like to learn more about Stuart Robinson on Presbyterians of the Past, then read “Stuart Robinson’, 1814-1881.”

Note that Dr. Robinson’s nearly 7,000 word article has been transcribed and edited by the author of this site, so please read about its use either by pressing the “Copyright and Use” button on the homepage tool bar. The footnotes are at the end of the transcription; the references to those notes have been included in their original locations in the text in [ ]. The paper was originally delivered to a gathering of ministers, college and seminary professors, ruling elders, and informed lay, so it assumes a good bit of prerequisite knowledge of theological subjects–it may be slow going for those without the prerequisite knowledge. The editor has chosen to add italics to the text in some cases for emphasis that likely would have been expressed visually and vocally by Robinson during the delivery. Essentially, the paper is as it was published. Dr. Robinson’s book, The Church of God an Essential Element of the Gospel, 1858, was reprinted, 2009, by the Orthodox Presbyterian Church with added material including Thomas E. Peck’s memorial for the author.

By many accounts, Dr. Robinson was a superlative and enthralling speaker. Unfortunately, his voice, manner, and appearance are lost to history, but with a little imagination maybe his presentation can be recaptured as he lectured from the podium with his rigid right arm, which had been injured as an infant, gesticulating stiffly while he gazed intently into the contemplative faces of his listeners.

Barry Waugh

The Churchliness of Calvinism: Presbytery Jure Divino its Logical Outcome

Stuart Robinson

(edited by Barry Waugh)

The venerable Dr. Charles Hodge of Princeton once related to the writer how on a certain occasion he was pressing Dr. J. Addison Alexander to write a brief treatise on the Church, as he had some time previously promised to do, under the title, “Presbytery tested by Scripture,” that remarkable man responded in his peculiar blunt way, “If you will write the first chapter, and tell me what the Church is, I will finish the book.” Such answer from so profound a scholar and thinker as Dr. Alexander is very significant as indicating that three centuries after the Protestant Reformation the leaders of Protestantism had not yet determined what the Church is, though they had so clearly determined three hundred years ago what it is not, in overthrowing the spiritual corporation which Rome had set up under the pope and declared it to be no Church. The suggestion of the Princeton Professor goes to confirm the observation of the philosophic German thinker, who before had suggested that of the four great departments of revealed truth—Theology, Anthropology, Soteriology, and Ecclesiology—the first three had been developed successively by the labors of Athanasius, the second of Augustine, and the third of Luther and Calvin, leaving the fourth yet to be developed. And it is a noteworthy fact, in confirmation of both suggestions, that while Evangelical Protestantism, or what may be called the original Protestantism, has since the Reformation been in the main a unit in regard to Theology, Anthropology, and Soteriology, and a unit also in the protest against the ecclesiological theory of Rome, but there has been little unity in regard to the question of the visible Church, nor indeed much toward settling the idea, nature, functions, and relations of the Church of Christ on earth. No broad platform of ecclesiology has yet been found upon which all Protestants may stand as substantially agreed.

It is not the purpose of this essay to point out the several causes of the diversities of Protestantism in the matter of the Church organized and visible, nor to inquire particularly as to why the remarkable doctrinal consensus on other great points of theology of the Churches of the Reformation should not long since have led to a like consensus in regard to the doctrine of the Church. Yet it may be proper to refer in passing to certain secondary causes which have tended strongly against such a consensus. Among these may be cited, in chief, the fact that the secular governments of Europe, having themselves first been emancipated from the Papal tyranny, were very jealous of all spiritual power; and very imperfectly comprehending the religious rights of men, would not suffer the organization, within their limits, of the Gospel Church as a “Free Christian Commonwealth,” nor recognize the autonomy of the Church as a “kingdom not of this world.” On the other hand, Protestants, assailed by the Pope with the legions of Caesar at his back, were obliged to take shelter behind their civil governments, and to sacrifice, in consideration of such shelter, the spiritual independence of the Church. They were constrained to admit the authority of the sovereign, to a greater or less extent, in regulating the form and prescribing the functions of the Church. Thus the Protestant Churches became national Churches, modified as to their structure and functions to suit the views of their political protectors. In consequence of this, usages, statutes, and institutions, binding the Church more and more closely to the secular governments, were gathered around these Reformed bodies. These in turn gave rise to civil enactments, Erastian in their spirit, until the standard authorities on public law in Europe came to reason with Emer de Vattel that “a nation ought to be pious, and its rulers should choose for the people the best religion, and prohibit the teaching of any other.” This became the source of most of those diversities and sects which have furnished color for the Papal clamors against the “variations of Protestantism,” and its supposed inherent tendency toward a multitudinous sectarianism.

Yet, while all this is true, it is by no means the whole truth as to the causes of the failure of the Churches of the Reformation to develop fully the doctrine of the one Catholic Church as organized and visible. It will be found, upon a careful examination of the confessions of that era, that though some of the fathers of the Reformation caught glimpses, and others clear views, of the Church visible, as the development in time of the body elect of God in the purpose of redemption—the kingdom not of this world—yet as the conflict waxed hot, and they were driven to shelter behind the secular power, they were restrained from the development of this germinal idea fully and symmetrically in the actual Church. So early a Reformer as John Huss presented, in opposition to the Papal conception of the Church visible, as an incorporated hierarchy for the administration of the grace of God, his conception of the Church invisible as the whole body of the elect of which Christ is the Head. Yet how this invisible body is to become, as to its earthly part, an organized reality he took no steps to expound. Still this conception of the Church, as a communion of believers, whose salvation is by grace through the work of the Holy Ghost sanctifying through the truth, was a long and bold step in advance. Luther, starting with this conception of the Church, declared that “all Christians are a truly spiritual order without any official distinction among them,” and held further, that “the Church visible is the collection of all believers in Christ on earth, the communion of all who live in the true faith and love and hope.” Like Huss, however, he conceived of no means by which this hidden Church is to become manifest as one visible body with visible ordinances. While he conceived that the ministers of the Church must derive their powers from the people, he was soon driven, by the disorders of Anabaptist fanaticism, to accept the idea of the State alliance and of control by the State so far as to preserve outward quiet in the administration of the Church’s affairs. Yet he still insisted that the sovereign held his power in the Church, not as a civil ruler, but only as an evangelical Christian, by a confiding act of conveyance from the Church. He maintained that the clergy have the spiritual power of the keys, while the civil government, through its superintendents, has the control of its external affairs; the result of all which was, that the right of the people to elect their pastors was lost and the Church became a mere appendage of the State.

Zwingli’s conception of the Church was not unlike that of Luther: “All those who live in Christ the Head are the sons of God. This is the Church or communion of saints, the spouse of Christ, the Church Catholic.” And a similar want of completeness in the definition of the visible Church as an organized body on earth will be noticed in all the confessions of the Reformation, which took their tone from the teachings of Luther and Zwingli.[1] They provided for no such outward organization of the “congregation of faithful men in which the Word is purely preached and the sacraments rightly administered” as shall represent the unity of all in some visible organization of the body on earth of which Christ is the Head.

Does not this deficiency in the definition of the Church arise in large part from a deficiency in the structure of the Zwinglian and Lutheran theories of revealed theology? The Papal theory, against which they all protested, like the ancient mythological theory of the physical universe, was constructed in large part out of legends and dreams, and scarce pretended to have any other foundation than mere human fancies, and its general prevalence among men. And just as the Ptolemaic, the Copernican, and the more modern theory of the “Mécanique Céleste,” are successive protests against the astrologic fancies of the old mythological system, and the prejudices of men, and by each of them the fundamental facts of the cosmos had, in some sort, their explanation, but in different degrees of consistency, clearness, and beauty—so with the three Protestant theories of theology. The Zwinglian, taking as its central principle for the construction of a theory of theology the great truth that the Word of God alone can be the authoritative rule to the conscience, constructed a true in opposition to a counterfeit gospel theology. Yet it is a gospel too liable to perversion by reason of its tendency to exalt the reason of man and make that the center of the spiritual system; or at least, by reason of its contractedness of view, to obscure some of the higher truths of the scheme of redemption. The Lutheran theory, taking as its central principle the justification of the sinner by grace alone through faith, after the fashion of Copernicus, exhibited Jesus Christ, “the Sun of Righteousness,” as the real center of the gospel system toward whom the rational man of earth and all his system is attracted, and around whom he revolves. But Calvin, while recognizing the central truths of both Zwingli and Luther as great truths, yet with the still wider vision of La Place and the moderns, conceived that not only the rational man, with the Word of God as the rule of his conscience, revolves around the Mediatorial Sun of Righteousness as his true center, but that this “Sun of Righteousness,” with all his system, revolves again around a still profounder center—even the eternal purpose of God, fixed in the counsels of eternity before the world began.

According to Calvin’s system this eternal purpose of God is the central truth of all revealed theology. Following closely the inspired Paul, and after him Augustine, he conceived that all that has transpired under the reign of grace, and the administration of Providence since time began, is but the gradual manifestation in time of the purpose formed from eternity.[2] Not only is the revelation which God has made of himself in his Word the publication, in time, of the proceedings held in the counsels of eternity; but the revelation of himself, experimentally, in the souls of his people, is but the manifestation of “the love wherewith he loved them before the world began.” According to this theory of theology, every truth of Scripture is to be conceived of as having its significance determined from its relation to the previously existing purpose in the Divine mind. So that the doctrine of the decrees of God is not so much a doctrine of Calvinism—one truth in a system of truth—as a point of view from which to contemplate all the doctrines of the gospel, or as a mode of conceiving and setting forth the truths of the revealed theology. Now, in the peculiar mode of that eternal purpose of salvation is to be found the true basis upon which the Church of God, as organized and visible, rests. For it is a distinguishing feature of the purpose of redemption that it proposes to save not merely myriads of sinners as individuals, but myriads of sinners as constituting a mediatorial body, of which the Mediator is the Head—an organized community of which Jesus Christ is the King—a Church, the Lamb’s Bride, of which he is the Husband, whose beautiful portrait was from eternity “graven upon the palms of his hands,”[3] and so that he may never raise his hand either to strew his mercies upon a sinful world, or to strike with the rod of his wrath, but he shall see that portrait and be reminded of the one great object of his Mediatorial administration.

The mission of Messiah to execute the covenant of eternity was not simply to be a teaching Prophet and an atoning Priest, but a ruling King as well. His work, besides making an atonement, was not, as a Socrates, merely to enunciate certain truths and found a school, but likewise, as the result of all and the reward of all, to be a Solon, founding a community, organizing a government, and administering therein as a perpetual King. Hence, therefore, the Church of God, as organized and visible, is but the actual outworking of the purpose to redeem an organized body of sinners out of the fallen race. It is, therefore, an essential element of the gospel theology. The foundations of the structure are laid in the very depths of the scheme of redemption; and the development, in time, of that scheme to redeem not merely individual souls, but a body of sinners organized under the Mediator, as Head and King, must of necessity develop a Church, visible and organized, as a part of the revelation to man of the counsels of eternity.

It is plain, therefore, that the too current conception of the question of the Church visible as something non-essential or even apart from the gospel, arises from deficient views of the gospel itself. The popular notion which finds expression in the dogma, “preach the gospel to sinners, and let these Church questions alone,” has its root in a defective idea of the gospel. For what if this question of the Church is an important part of the gospel? To preach nothing of the Church is to preach a mutilated gospel. And sinners converted under such preaching that are led to believe they are converted as independent individuals who stand in no churchly relations other than as grains of sand aggregated in the heap, inevitably will prove to be very imperfect Christians. The true gospel preaching will cause sinners to see that when born again they are born into the family of God and into new relations to every other member of that family, to live henceforth not independent and apart, but as entering into citizenship by the communion of saints under a Divinely organized government—“a kingdom not of this world.” And this kingdom, in its perfect development, should recognize no national distinctions, nor divisions of “Barbarian, Scythian, bond, or free,” but instead constitute one visible Church of God.

According to the Calvinistic theory, as the general ideal purpose of God becomes actual and revealed in time, so every part of that purpose has its corresponding manifestation. The Mediator of the ideal covenant becomes Jehovah manifesting himself in various ways as the Angel of the covenant, the King in Zion, the Word made flesh. The ἐκλεκτοί of the eternal covenant become the actual κλητοί (called ones) of the manifested purpose. In as far as they are κλητοί by the Word merely, they are gathered in to constitute the external ἐκκληςία on earth. In as far as they are κλητοί also by the internal κλῆσις of the Spirit, they are gathered to constitute the invisible ἐκκληςία—the full and complete actual of the eternal ideal. On the Calvinistic theory, therefore, the Church visible is, in the logical order of thought, the development, in time, of the ideal body of the eternal covenant of redemption. It is at once the form in which the purpose is manifested, the agency through which the whole counsel of God is revealed, the institute for the calling and training of the elect, and the development of the Church actual according to the eternal “pattern in the heavens.” We must conceive, therefore, of the Church visible as beginning to exist with the first sinners saved, and continuing the same Church in reality, however changing its form while the revelation was in progress, till the last of the elect be gathered in.

It will be found that by this theory of Calvinism the clue is furnished for the clear and consistent interpretation of the Scriptures. And it will especially be found that on this theory the teaching of the Scriptures concerning the idea, nature, and functions of the Church visible are made plain in a degree that they cannot be on any other theory. All that they teach goes to show the existence of a visible Church substantially one and the same in all ages. The very mode of the revelation of God by a series of successive covenants, each a fuller development of the preceding, involves the idea of a distinct body on earth with which these covenants are made, and through which they have their historical development. The very first gospel covenant, “I will put enmity between thy seed and her seed,” divides the whole race, and separates a peculiar people that “call upon the name of Jehovah,” from the body of the race at large. So the covenant with Abraham is in the nature of a great charter, organizing a separate community; it is for this reason that Abraham stands forth so pre-eminently in Scripture, beyond even Adam, the first, and Noah, the second head of the race. We can account for this preeminence only on the ground of the importance in the scheme of redemption of the visible Church as a separate social organization apart from that of the family. With this organization were all subsequent covenants made, and through it all subsequent revelations. To it, says the Apostle, “were committed the oracles of God.” God’s revelation is not primarily to mankind at large, but to his Church, and through his Church to mankind.

Just as in the process of creation, though the light was the result of the first day, yet midway between the beginning and the end stands the work of the fourth day—the sun, the gathered light organized under natural law for the permanent illumination of the earth; so while the elements of the Church visible began to exist from the call of the first sinner to light out of darkness, in the covenant with Abraham, midway between the beginning and the finishing of the work of redemption, the rays, hitherto diffused in the family, were organized into a visible Church, constituted under the law of its being the agent, henceforth, for the diffusion of the divine light over the world. All subsequent covenants, as with the “Church in the wilderness,” at Sinai, and with David establishing the typical throne, are but the further elucidation and confirmation of the great Church covenant with Abraham. And all are for the development of the redemption promised as the founding of a community of which Messiah is to be king. So far from occupying a secondary place, as in much of our modern theology, the doctrine of Messiah as King, ruling over an organized community, is made more prominent in the Scripture than even the doctrine of Messiah as a prophet and an atoning priest. It may be said, indeed, that the doctrine of Christ as King constitutes the last and highest development of the Mediatorship, both in the Old and New Testaments. He is exhibited as the Prophet revealing all, and the Priest redeeming all, in order for him to be the King that rules all. The governmental aspect of the work of redemption has a prominence in Scripture which fully justified the zeal of the Scottish martyrs in testifying to the death for “Christ’s crown and covenant.”

Thus it appears that the very structure of the Scripture implies the existence on earth of a Church visible. Nor is it difficult to show that this Church has been one and the same body in all ages, having the same objective fundamental creed, the same subjective spiritual experience, and the same general principle and form of administration. As to the objective creed of the Church, an inspired Apostle compresses it all in two words, “We preach Christ crucified;” and the Scriptures show that this is the fundamental creed of the Church, whether as preached prophetically through types and symbols, or historically in literal terms. The gospel story opens with Abel’s confession of salvation by substitution, even through an atoning Savior, by the lamb slain, and of Jehovah’s acceptance of him, on the ground of his faith in the substituted victim. In the story of Abraham, two thousand years later, the same truth is held forth in the call for the lamb of the father’s own heart. Four hundred years later again, under Moses, the same gospel is held forth in the lamb whose blood was sprinkled on the door-posts, and in the lamb which ever figured in the gorgeous sacrificial ritual of the tabernacle. In the visions of Isaiah, seven hundred years later, the same truth is held forth in the prophetic view of Messiah as “the lamb led to the slaughter.” Another seven centuries, and John the Baptist announces the opening of the new dispensation with the cry, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world!” And in the final closing of the revelation, John the Evangelist, through the door opened in heaven, catches a glimpse of the glorious Church of the future, having still for the central object of her adoring worship, “the Lamb in the midst of the throne.”

And as the objective creed of the Church varies not from age to age, so the subjective theology in the experience of believers in the Lamb slain, finds expression in the same terms. In the “Church in the wilderness,” Christ was presented in the water from the smitten rock for the thirst of the soul. For, says the Apostle, “that Rock was Christ.” In the era of David, the sole utterance of the believer still was, “My soul longeth, yea thirsteth for God.” In the gospel offer of Isaiah, the invitation is still, “Ho! every one that thirsteth.” As proclaimed by the Word Incarnate, it is still, “If any man thirst, let him come to me and drink.” And as proclaimed under our dispensation from the throne of glory, to which, sixty years before, He had ascended, it is still, “Let him that is athirst come.” And in the vision of the Seer in Patmos appear the waters of the river of life flowing from the throne of God, as the emblem of the thirst of believers quenched forever.

Not only is the creed and the subjective position of the Church for four thousand years the same, evincing it to be one and the same body under all dispensations, but the principles of its government are the same under every variety of dispensation. The invisible King carries out the government of it through visible officers of his own appointment, whom yet the people shall call to the exercise of their offices. The David formally appointed by Jehovah himself must yet struggle on through long years of evil and danger, until the voice first of Judah and then of all Israel shall call him to the exercise of the office to which Jehovah so long before appointed him. And after the same manner all Church rulers are appointed. Even the manner of administration of this government in the visible Church is seen to be the same, viz., never at any time by one man, but always by tribunals of elders, alike in every era. So soon as by the shortening of human life the Church could no longer be embosomed in the family and governed by her patriarchs, or natural elders, and it became needful to organize both Church and State as institutions apart from and over the family institutions, it would seem that, both in State and Church, elders chosen to the office took the place of the patriarchs. For before the national organization under Moses it appears there were elders ruling over the covenant people; and to the Presbytery Moses himself must needs exhibit the evidences of his call of God—the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob —to the work of executing the provisions of the ancient covenant by the deliverance of his people from bondage. Through the elders the ordinance of the Passover was given to the Church. Before the elders, as representatives of the Church, was the rock smitten. To the Church, through her elders, after solemn preparation, were the revelations at Sinai made, and these in form of a solemn covenant between Jehovah and his people. The elders partook with Moses of the solemn sacrificial feast in the Mount preparatory to the reception of the ritual and ecclesiastical law. The elders, with the priests, constituted the ecclesiastical court of appeals of the nation. Even in Israel under the apostasy this form of government remained unchanged among the true people of God—for “Elisha sat in his house and the elders sat with him.” And after the fall of Israel as a nation, the elders assembled with the prophet Ezekiel in their captivity on the river Chebar. So even in the wasted and corrupt Jerusalem, the form of this appointed court, the presbytery, survived the apostasy; for we learn that a corrupt court of priests and elders condemned Jeremiah to death for speaking the warnings of Jehovah. When Messiah “came unto his own, and his own received him not,” even then, at the final apostasy of the Church of the old covenant, the divinely-appointed form of ecclesiastical government is found still surviving, though men “made void the law through their traditions.” Elders ruled in the synagogues, and priests and elders constituted the ecclesiastical council that condemned the Son of God. For though they were apostate in doctrine, the old form of government still stood. Under the dispensation of the Spirit, the elders still occupied the same position toward the Church that they had occupied under the old dispensation, having been appointed by the Holy Ghost to take oversight of the flock. And again in the vision of the Seer in Patmos, he beheld through the door opened in heaven the growing Church of the future—a great congregation still organized as a Church, represented by its elders—four-and-twenty—twelve for the old, and twelve for the new dispensation; these elders are casting their crowns, the symbols of their authority, at the feet of Him whom they unite to acknowledge as the head and source of all authority in the Church of all ages.

Thus the Calvinistic theory of the Church is seen to be in perfect harmony both with the structure and the substance of the Scriptures. The primary and germinal idea of the Church is of that elect body contemplated in the covenant of redemption. As the eternal purpose becomes manifested in time, through external instrumentalities, the ideal ἐκλεκτοί became the ἐκκληςία, the “called out” and separated body of men. By a covenant charter this body is organized into a community in which the Mediator rules, to which he gives ordinances, laws, and officers, and through which he will reveal his will and execute his mission to the race at large. This organized body, in the nature of the case, is perpetual and identical through all ages. It may vary in degrees of purity down to utter apostasy. It may have its seat in one nation and run in the line of natural descent, or it may become the Church of all nations, and treat as one blood all the kindred of men. It may now be conspicuous, or now humble and comparatively hidden. It may vary as to the degree of divine knowledge current in it, and may vary as to the form of its ordinances and instrumentalities for teaching divine truth. But withal, it is essentially the same body of people, organized for the same purposes, administered in by the same Ruler, and under him ministered to by the same sort of ministering servants, and substantially under the same form of government —elders in tribunals.

The Scriptures, in speaking of this Church, bring into view this remarkable peculiarity of it, that in the definition of the Church visible the term may properly be taken in every variety of extent—and this doubtless for the reason that every part of it, as well as the whole of it, is the development in time of the ideal Church of the eternal purpose to redeem a body. So that as it is gravitation—involving the same general idea—whether as embodied in the apple falling from the tree in the sight of the philosopher, or in the earth moving around the sun in its orbit, so this body is the Church of God, whether it be the organization of the little handful in the house of Priscilla, or the church composed of all the saints that are in Philippi, or the church of many congregations at Jerusalem or at Antioch, or the Church at large, which suffered persecution, or the “general assembly and church of the first-born,” embracing all the redeemed. The power of the whole is in every part, so that when the little church that is in the house of Priscilla speaks in Christ’s name, through its tribunal, it is the Church of God that speaks. Yet, at the same time, the power of the whole is over the power of every part, so that when the whole body, as represented in the General Synod at Jerusalem, speaks, saying “It seemed good to the Holy Ghost, and to us,” the power of every part must be exercised in accordance with this deliverance. As every part, in diversity of extent, is the Church, so these various parts must necessarily have tribunals representing them from the tribunal of elders which governs a single congregation upward through tribunals representing various extents of the meaning of the term Church, on to the tribunal of elders which represents the whole body of the Church on earth.

Another point should here be noted, viz., that in all the Scripture there is no instance recorded of an exercise of governmental authority in the Church by individuals, saving and excepting the inspired Prophets and Apostles. It is ever by tribunals. Nor is there named any other order of governmental officers composing these tribunals than the πρεσβύτεροι (elders). However largely the term ἐπίσκοποι may have figured in Church history since the Apostolic age, it is used but four times in the New Testament as descriptive of a church-officer (as against the use of πρεσβύτεροι some seventy times), and then ἐπίσκοπος is used only in speaking of or to Greek Churches, as defining to them the meaning of the common ecclesiastical term πρεσβύτεροι, with which Gentiles could not be familiar. So that from first to last the term that precisely represents the Scriptural form of church-government in every age is the term “Presbyterian.”

Such, then, is the general conception of the Church visible, logically developed from the Calvinistic theology of the eternal purpose of God to redeem a body of sinners out of the fallen race. The only logical outcome is Presbyterianism, and all Church history testifies to the fact that only in connection with a Presbyterian Church government can the Calvinistic doctrines long be preserved pure. A reference to the Calvinistic creeds of the Reformation will show that the theory of the Church here developed was plainly the conception which Calvinists then had, however they may have failed afterward to maintain it fully. Some of them more fully, some less, brought out the conception of the Church visible as the manifestation of the Church ideal of the purpose of redemption.[4] In the Westminster Confession, the Church is defined fully, and as a point of the Calvinistic doctrine. The entire definition extends through three paragraphs, containing in their logical order the three elementary ideas which enter into the conception of the Church as a complete whole, one paragraph being given to each. First is defined the Church ideal of the eternal purpose. Second, this ideal as manifest and actual in the Church visible. Third, this visible Church as an organic body receiving visible officers, laws, and ordinances from her great Head.

It may now be asked why, with this clear conception of the Church, so far in advance of the conception of other than Calvinistic Churches at the Reformation, the Calvinistic Churches have also, in great measure, failed to actualize their ideal. The answer is not difficult. In the first place, such a theory of the Church naturally excited the hostility of the secular governments of the world, because to their Erastian conceptions it seems to set up within their dominions an imperium in imperio, leading their subjects to say, “There is another King, one Jesus.” Hence the peculiar hostility of the civil sovereigns and Erastian jurists against Presbyterianism. And hence the peculiar form of the testimony of the Scottish fathers for Christ’s crown and covenant.

It has been a very current blunder among even men of letters to confound the Scottish Presbyterians, in the contest with the Tudors and the Stuarts, with the English Nonconformists under the common title of Puritans, whereas the Scottish Puritan, if he must be called such, had no sort of ecclesiastical affinity with the English Puritan. For, while the one was inherently a radical and a republican, the other was inherently a conservative and a royalist. Their only affinity was in the common struggle against tyranny and prerogative. The English Puritan fought the Stuarts primarily because they trampled upon his individual rights as a man and his liberty of conscience. The Scottish Puritan fought the Stuarts primarily because they dared to invade Christ’s crown rights in his spiritual kingdom. The one fought as a man for his rights, the other fought as a loyal subject of King Jesus. The key to the entire history of Scotland for two centuries after the Reformation is found in the fact that Scottish Protestantism accepted so fully the Calvinistic theory of theology and its logical outcome, Presbyterianism. And they established their Church on that theory just in so far as their secular government would allow them to do it.

Perhaps another cause of the imperfect development of this theory of the Church has been the mistake of many earnest Presbyterian men, who, failing to perceive the logical connection between Calvinistic theology and the Presbytery for church-government, have supposed that the peace and unity of Christ’s earthly kingdom might be promoted by fusing together with one or other of the two great Protestant antagonists—Independency on the one hand, and Prelacy on the other, more especially the former. It would be supposed that any intelligent Presbyterian would see so clearly the incongruity of Presbytery and Independency as not to fall into the error of seeking to blend them. For Independency in reality recognizes no organic Church visible, and Prelacy conceives of the organic Church visible, of which it makes such parade, as merely the spiritual incorporation of a ministry as the channel through which the grace of God is administered to sinners, and its prelates the authority by which the people are to be ruled. Yet the movement represented by the Westminster Assembly was really an attempt to find a via media between Presbytery and its two antagonists, particularly between Presbytery and Independency. The natural outworking of such an attempt is seen in that where the proposition for Presbytery jure divino was pressed by the Assembly upon the Parliament and rejected, the remonstrances of the indignant Assembly against the treachery of their allies, the Independents, who had the power in Parliament, were silenced by the threat of praemunire. And it is a striking illustration of how error, once submitted to, soon loses its deformity, that the fathers of the American Church, who were free to develop their Presbyterianism with none to molest or make them afraid, instead of going back to the jure divino assertion of Presbytery by the Westminster Assembly, adopted the Parliament’s substitute of Presbytery by expediency, against which their grandfathers had testified so earnestly as dangerous and dishonoring to Christ’s ordinance (see, American Presbyterian Form of Government, chapter 8th).

The very common prejudice against the doctrine of Presbytery by Divine warrant, flowing thus logically from the Calvinistic theology, as “High Churchism,” generating a narrow sectarianism, has its origin in indistinct views of the teaching of Scripture concerning the Church. If it be not narrow sectarianism to hold the doctrine of God’s eternal decree as set forth in chapter third of the Westminster Confession, why shall it be deemed narrow sectarianism to hold and bring out in its fullness the doctrine of the Church as set forth in the twenty-fifth chapter, which is but the logical sequence of the third chapter? If it does not unchurch other bodies of Christians to assert that they err in rejecting the doctrine of the third chapter, why does it unchurch them to assert that they err in not accepting the twenty-fifth chapter?

A clear apprehension of the Divine appointment of all that pertains to the ordinances and government of the Church is the surest guarantee of earnest spiritual views of the ordinances and order of the Church. With such views, not only will the ministry of the Word and Sacraments assume more of its truly spiritual and unworldly character in the minds of both minister and people, under a consciousness of the presence of the Holy Ghost in the ordinances, but the courts of the Church also will assume more of their peculiar sacredness as courts of Jesus Christ, the true source of their authority, by whose Spirit alone they can be guided to right conclusions. With clear views of the nature and functions of the Church visible guiding Church Sessions, Presbyteries, Synods, and General Assemblies, the Church would rise to nobler views of the communion of saints, and more rapid would be the advance toward that era when the unity of the one visible Church as the manifestation of the eternal purpose of redemption shall be represented in one grand Ecumenical Assembly, in which the people of God of all nations and climes shall be represented.

Nothing has been said in this paper of the theories of ecclesiology which trace the visible Church of God no further back than the Apostles, nor of the popular error that because little is said expressly in the writings of the Apostles of the form of church government, therefore it must be a matter of minor importance. It will be seen that, according to the views here presented, the Church of God as a visible organization had already become venerable in the age of the Apostles. They had no commission to establish a Church constitution, but simply to modify the constitution so far as to allow the Church of the one nation to become the Church of all nations, and to modify the ordinances of the Church so as to substitute the forms of worship proper to the worship of Christ as historically incarnate, for the symbols needful for the worship of Christ while his incarnation was yet future. The function of the Apostles was similar to those of the American Conventions called to modify the State constitutions so as to adopt them to the changed circumstances of the people in that rapidly growing country. Hence they had so little to say of church government, and of the ordinance of infant baptism, and of other topics on which they must have spoken fully had the Christian Church then had its first institution.

[1] Thus the Confession of Augsburg: “Ecclesia est congregatio sanctorum in qua evangelium recte docetur et recte administrantur sacramenta. Nec necesse est ubique esse similes traditiones humanas seu ritus aut ceremonias ab hominibus instituta.

So Confessio Anglicana, Art. 19: “Ecclesia Christi visibilis est coetus fidelium, in quo verbum Dei purum praedicatur, et sacramenta, quoad ea quae necessario exiguntur, juxta Christi institutum recte administrantur.”

So the Confessio Basileensis prior: “Credimus sanctam Christianam ecclesiam, id est communionem sanctorum, congregationem Fidelium in spiritu: quae sancta et sponsa Christi est: in qua omnes illi cives sunt qui confitentur Jesum esse Christum Agnum Dei tollentem peccatum mundi atque eandem per opera Charitatis demonstrant.”

[2] Eph. 1:4-12, and 3:9-11; Rom. 8:28-33; John 17:2-5.

[3] Isaiah 49:16.

[4] Thus, Confessio Helvetica Post., Art. 17: “Et cum semper unus modo sit Deus, unus mediator, unus item gregis universi pastor,” etc., “necessario consequitur unam duntaxat esse ecclesiam. Et militans in terris ecclesia semper plurimas habuit particulares ecclesias quae tamen omnes ad unitatem Catholicae ecclesiae referuntur. Haec aliter fuit instituta ante legem inter patriarchas, aliter sub Mose per legem, aliter a Christo per evangelium.”

So Confessio Gallicana: “Itaque affirmamus ex Dei verbo ecclesiam esse fidelium coetum qui in verbo Dei sequendo et pura religione colenda consentiunt.…”

Art. 29: “Credimus veram ecclesiam gubernari debere ea politia sive disciplina quam Dominus noster Jesus Christus sanciavit ita videlicet ut in ea sint Pastores Presbyteri, sive seniores et Diaconi.…”

With this accords exactly the Confessio Belgica, Art. 30.

The Confessio Scoticana more explicitly in Art. 16: “Sic ut in unum Deum, Patrem Filium et Spiritum Sanctum credimus, ita etiam ab initio fuisse et nunc esse unam ecclesiam constanter credimus, id est societatem et multitudinem hominum Deo electorum qui illum recte per veram fidem in Jesum Christum colunt, et amplectuntur, qui ejusdem ecclesiae solus est caput quae etiam, est corpus et sponsa Christi Jesu: quae ecclesiae est Catholica, id est universalis, quia electos omnium seculorum, regnorum, nationum et linguarum continet,” etc.

Eph. 1:22, and verse 33; Col. 1:18; Rev. 7:9.