The following article is about the marriage of Prince William and Catherine Middleton in England. It is the first of some occasional articles that will be posted for the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s posting of his theses in Wittenberg. Even though interest in the wedding in 2011 has passed, one of the ministries provided by pastors is conducting weddings and the following will explain the history of some terminology used not only by Anglicans and Presbyterians, but also other denominations.

The Royal Wedding

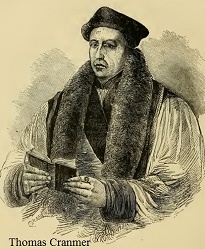

On April 29, 2011, people all over the world were watching the marriage ceremony for Prince William and Catherine Middleton. People were glued to their televisions for sundry reasons—some wanted to see Catherine’s gown, others looked for dignitaries and celebrities entering Westminster to attend the event, some of the older folks wanted to see how Queen Elizabeth II was dressed, but how many were glued to the tele to see two people married in the sight of God is debatable. The presiding clerics were Dr. John Hall, Dean of Westminster, who did the first portion of the service, and then Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England conducted the ceremony, presented the vows, and concluded with a brief sermon. There were some attending and others that watched on television who would have known about the history behind the Anglican wedding ceremony, but it is likely that the great mass did not. Much of the ceremony can trace its words back to another Archbishop of Canterbury that served 1533-1553, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556). Archbishop Cranmer composed The Forme of Solemnization of Matrimonie in his worship book published in 1549 for the Church of England. Thomas Cranmer had served King Henry VIII and continued to serve when his son Edward VI was crowned following Henry’s death. The following will take a look at the history of a portion of the marriage ceremony and how it relates to the Royal Wedding.

On April 29, 2011, people all over the world were watching the marriage ceremony for Prince William and Catherine Middleton. People were glued to their televisions for sundry reasons—some wanted to see Catherine’s gown, others looked for dignitaries and celebrities entering Westminster to attend the event, some of the older folks wanted to see how Queen Elizabeth II was dressed, but how many were glued to the tele to see two people married in the sight of God is debatable. The presiding clerics were Dr. John Hall, Dean of Westminster, who did the first portion of the service, and then Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England conducted the ceremony, presented the vows, and concluded with a brief sermon. There were some attending and others that watched on television who would have known about the history behind the Anglican wedding ceremony, but it is likely that the great mass did not. Much of the ceremony can trace its words back to another Archbishop of Canterbury that served 1533-1553, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556). Archbishop Cranmer composed The Forme of Solemnization of Matrimonie in his worship book published in 1549 for the Church of England. Thomas Cranmer had served King Henry VIII and continued to serve when his son Edward VI was crowned following Henry’s death. The following will take a look at the history of a portion of the marriage ceremony and how it relates to the Royal Wedding.

The historical story begins with the tumultuous reign of England’s King Henry VIII. For years the reign of the obese and pragmatic monarch has entertained reading and viewing audiences with its intrigue, lust, and deception as exemplified in the 1970 television series The Six Wives of Henry VIII and by Allison Weir’s 1991 book with the same title. Marriage increasingly influenced the rule and decisions during Henry’s reign due to his obsession, common to kings, to father a strong, intelligent, and crafty son to succeed him on the throne. However, Henry had a real problem fathering that robust son due to complicating factors with his successive wives. He spent a considerable portion of his rule finagling and maneuvering people and powers to achieve his end—a male heir to the throne.

The historical story begins with the tumultuous reign of England’s King Henry VIII. For years the reign of the obese and pragmatic monarch has entertained reading and viewing audiences with its intrigue, lust, and deception as exemplified in the 1970 television series The Six Wives of Henry VIII and by Allison Weir’s 1991 book with the same title. Marriage increasingly influenced the rule and decisions during Henry’s reign due to his obsession, common to kings, to father a strong, intelligent, and crafty son to succeed him on the throne. However, Henry had a real problem fathering that robust son due to complicating factors with his successive wives. He spent a considerable portion of his rule finagling and maneuvering people and powers to achieve his end—a male heir to the throne.

Henry VIII’s marriage difficulties began with his brother’s wife. In 1502 a marriage was arranged by Henry VII between his eldest son, Arthur, and Catherine of Aragon, who was the daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. In arranging the marriage, Henry VII was doing what royalty often did which was use their children’s marriages to achieve political or military purposes. In this case, the marriage would strengthen England’s ties to Spain as they both opposed France. Arthur was Henry VII’s oldest son, seventeen at the time, and he was one year younger than Catherine. Arthur and Catherine were married and within five months Arthur died. The next in line for the throne was Prince Henry, who was only twelve years old in 1503. With Arthur dead, King Henry VII wanted to arrange for Prince Henry to marry widow Catherine.

But there was a very sticky wicket in the path of Henry VII’s plan for Prince Henry’s marriage. If Henry was to marry Catherine he would be marrying his deceased brother’s wife. Mosaic Law prohibited a man marrying his deceased brother’s wife due to the exclusion of such marriages in Leviticus 18:16, which reads, You shall not uncover the nakedness of your brother’s wife; it is your brother’s nakedness. The enforcer of the Law of God upon monarchs and other church members was the papacy, so Henry needed to find some way to obtain permission from the pope for the near-kin marriage. It is important to note that the use of Leviticus 18:16 to judge the marriage illegitimate was not the issue as much as the marriage was forbidden by Rome’s canon law. For Roman Catholicism, the Word of God is such as it is interpreted by the papacy. Over the centuries, Catholicism had developed a long history of expanding the biblical prohibitions against near-kin marriages so that the church laws exceeded the Law of God. Henry VII was able to convince Pope Julius to grant a document called a “bull” which allowed his son to marry Catherine in June after he had been crowned April 23, 1509. Henry VII had died earlier that year. When they married, Henry VIII was eighteen and Catherine was twenty-four years of age.

But there was a very sticky wicket in the path of Henry VII’s plan for Prince Henry’s marriage. If Henry was to marry Catherine he would be marrying his deceased brother’s wife. Mosaic Law prohibited a man marrying his deceased brother’s wife due to the exclusion of such marriages in Leviticus 18:16, which reads, You shall not uncover the nakedness of your brother’s wife; it is your brother’s nakedness. The enforcer of the Law of God upon monarchs and other church members was the papacy, so Henry needed to find some way to obtain permission from the pope for the near-kin marriage. It is important to note that the use of Leviticus 18:16 to judge the marriage illegitimate was not the issue as much as the marriage was forbidden by Rome’s canon law. For Roman Catholicism, the Word of God is such as it is interpreted by the papacy. Over the centuries, Catholicism had developed a long history of expanding the biblical prohibitions against near-kin marriages so that the church laws exceeded the Law of God. Henry VII was able to convince Pope Julius to grant a document called a “bull” which allowed his son to marry Catherine in June after he had been crowned April 23, 1509. Henry VII had died earlier that year. When they married, Henry VIII was eighteen and Catherine was twenty-four years of age.

By 1514 it was clear to King Henry that he would not have a surviving son from Catherine. She had five conceptions that delivered two miscarriages, two sons who died within a few weeks of birth, but the one surviving child was a girl, Princess Mary. By 1526, Henry was seeking an annulment of his marriage with Catherine as he pursued his interest in Ann Boleyn for his second wife. When Henry married Catherine the marriage had been approved by Pope Julius, but now he had to get an even thornier case past the current pope, Clement VII. King Henry pursued an annulment of his marriage by claiming that Pope Julius’s bull had been in error. He declared that the marriage to his deceased brother’s wife was against God’s Law. The pragmatic king said he had discovered in the Bible that his marriage to Catherine was barren because of the curse at the end of Leviticus 20:21, If a man takes his brother’s wife, it is impurity, He has uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless. Henry pushed his case for an annulment before Pope Clement VII. Catherine countered Henry by appealing to Rome in defense of the legitimacy of her marriage. The disfavored queen was concerned that if the marriage was deemed illegitimate, then Mary would also be considered illegitimate. All of the wrangling with Rome as well as canvassing the universities and scholars for opinions about the marriage came to naught, because after the extended interchange between Henry and Rome the matter was solved through another means. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of England provided the annulment that Rome refused to grant when on May 23, 1533, he announced his decision that the marriage of Henry VIII to Catherine had been invalid from its beginning and therefore was annulled. However, by this time Henry had already married Anne Boleyn in January 1533. Anne was crowned queen in May and Elizabeth, who would become Queen Elizabeth I, was born to her in September. For Henry VIII, the problem of the pope was ultimately resolved in 1533 when via the Act of Supremacy he declared himself the head of the church in England.

By 1514 it was clear to King Henry that he would not have a surviving son from Catherine. She had five conceptions that delivered two miscarriages, two sons who died within a few weeks of birth, but the one surviving child was a girl, Princess Mary. By 1526, Henry was seeking an annulment of his marriage with Catherine as he pursued his interest in Ann Boleyn for his second wife. When Henry married Catherine the marriage had been approved by Pope Julius, but now he had to get an even thornier case past the current pope, Clement VII. King Henry pursued an annulment of his marriage by claiming that Pope Julius’s bull had been in error. He declared that the marriage to his deceased brother’s wife was against God’s Law. The pragmatic king said he had discovered in the Bible that his marriage to Catherine was barren because of the curse at the end of Leviticus 20:21, If a man takes his brother’s wife, it is impurity, He has uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless. Henry pushed his case for an annulment before Pope Clement VII. Catherine countered Henry by appealing to Rome in defense of the legitimacy of her marriage. The disfavored queen was concerned that if the marriage was deemed illegitimate, then Mary would also be considered illegitimate. All of the wrangling with Rome as well as canvassing the universities and scholars for opinions about the marriage came to naught, because after the extended interchange between Henry and Rome the matter was solved through another means. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of England provided the annulment that Rome refused to grant when on May 23, 1533, he announced his decision that the marriage of Henry VIII to Catherine had been invalid from its beginning and therefore was annulled. However, by this time Henry had already married Anne Boleyn in January 1533. Anne was crowned queen in May and Elizabeth, who would become Queen Elizabeth I, was born to her in September. For Henry VIII, the problem of the pope was ultimately resolved in 1533 when via the Act of Supremacy he declared himself the head of the church in England.

Catherine was condemned to live out her days with no power and few friends within the Tudor household. For Henry, Catherine had been weighed in the balance of his favor and been found wanting due to her failure to give birth to a son who could accede to the throne. When Catherine died in 1536, Henry did not attend her funeral. However, Catherine would posthumously obtain a coup de grâce against King Henry when her Roman Catholic daughter Mary acceded to the throne in 1553 after the short Protestant reign of his only son, Edward VI.

Catherine was condemned to live out her days with no power and few friends within the Tudor household. For Henry, Catherine had been weighed in the balance of his favor and been found wanting due to her failure to give birth to a son who could accede to the throne. When Catherine died in 1536, Henry did not attend her funeral. However, Catherine would posthumously obtain a coup de grâce against King Henry when her Roman Catholic daughter Mary acceded to the throne in 1553 after the short Protestant reign of his only son, Edward VI.

It may be wondered at this point what all this history has to do with the Royal Wedding. Thomas Cranmer was the author of the first edition of The booke of the common prayer and administration of the Sacraments, and other rites and ceremonies of the Churche: after the use of the Churche of England, published in London in 1549. Included on page 331 of the digital edition of the book is The Forme of Solemnization of Matrimonie which begins with the following statements prefacing the order for the ceremony itself. The original spellings have been used to reflect the historical sense of the text.

first the bannes must be asked three several Soondaies or holye dayes, in the service tyme the people beeyng presente after the accustomed maner.

And if the persones that woulde bee maried dwel indivers parishes, the bannes must bee asked in bothe parishes, and the curate of thone parish shall not solemnize matrimonie betwixt them, withoute a certificate of the bannes beeyng thrice asked from the curate of thother parishe.

At the daye appointed for Solemnization of Matrimonie, the persones to be maried shal come into the bodie of ye churche, with theyr frendes and neighbours. And there the priest shal thus saye…

Before the couple and their guests gathered for the ceremony, the first step to be taken for marriage was asking the “bannes” (banns) in three previous services of the church, which raises the question, “What are banns?” As was seen in the case of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon there was an impediment to accomplishing the marriage because she was his deceased brother’s wife. Roman Catholicism had a lengthy list of prohibited near-kin relationships which included relationships of consanguinity, blood relations, and affinity, relations established through marriage. The kinship impediments to marriage continued to be enforced by the Church of England and by the time of Archbishop Matthew Parker during the reign of Elizabeth I, the kinship relations banned were listed and posted in each church, they were common knowledge. In asking the banns, the cleric was to question the congregations of both parties seeking marriage to see if anyone knew of any kinship between the man and woman within the prohibited degrees. If so, they were to inform a church official. Not only did the banns address issues of near-kin marriage, but also bigamy, remarriage of those who were divorced, and other impediments.

Following the introductory comments in the order of service, the Tudor era curate in charge would have read from Cranmer’s 1549 book the following words of the ceremony.

Derely beloved frendes, we are gathered together here in the syght of God, and in the face of his congregation, to joyne together this man, and this woman in holy matrimonie, which is an honorable estate instituted of God in paradise, in the time of mannes innocencie, signifying unto us the misticall union that is betwixte Christ and his Churche:…[etc.]

This sixteenth-century text with modernized language and some modifications was used in the ceremony for William and Catherine. However, a sampling of some of the changes to note include—in the 1549 edition it is said that marriage is “commended by Sainct Paule,” but in the current version as read during the Royal Wedding it is “commended by Holy Writ”; another change is that in the 1549 order it is said that marriage is not to be entered “to satisfie mens carnal lustes and appetites, like brute beastes that have no understanding,” which was removed in the Royal Wedding version; and in a final sample modification Cranmer’s version of 1549 reads, “One cause [for marriage] was the procreation of children, to be brought up in the feare and nurture of the Lord, and the prayse of God,” which was presented in the Royal Wedding as, “it was ordained for the increase of mankind according to the will of God and that children might be brought-up in the fear and nurture of the Lord and to the praise of his holy name.” The history and progression of editions between 1549 and the words used in the wedding for William and Catherine is a long one, but despite the changes that have been made, the 2011 ceremony was very much like the one penned by Archbishop Cranmer in 1549.

This sixteenth-century text with modernized language and some modifications was used in the ceremony for William and Catherine. However, a sampling of some of the changes to note include—in the 1549 edition it is said that marriage is “commended by Sainct Paule,” but in the current version as read during the Royal Wedding it is “commended by Holy Writ”; another change is that in the 1549 order it is said that marriage is not to be entered “to satisfie mens carnal lustes and appetites, like brute beastes that have no understanding,” which was removed in the Royal Wedding version; and in a final sample modification Cranmer’s version of 1549 reads, “One cause [for marriage] was the procreation of children, to be brought up in the feare and nurture of the Lord, and the prayse of God,” which was presented in the Royal Wedding as, “it was ordained for the increase of mankind according to the will of God and that children might be brought-up in the fear and nurture of the Lord and to the praise of his holy name.” The history and progression of editions between 1549 and the words used in the wedding for William and Catherine is a long one, but despite the changes that have been made, the 2011 ceremony was very much like the one penned by Archbishop Cranmer in 1549.

Later in Prince William and Catherine Middleton’s ceremony, the order returned to issues of consanguinity, affinity, and the banns. In Cranmer’s order, the banns were presented three worship days in advance of the service, that is, the ceremony could not begin without it being determined that the prospective bride and groom were not related in a degree sufficient to prohibit their becoming one flesh. In the Royal Wedding, the banns, which are no longer called by that name in the ceremony, were presented by Dean of Westminster John Hall in the following sentence.

Therefore, if any man can show any just cause why they may not lawfully be joined together, let him now speak, or else hereafter forever hold his peace.

These words were directed to those assembled for the wedding because they were not only present for personal and social reasons, but also, more importantly, to witness the wedding. It is at this point in the service that anyone assembled for the wedding was to get the curate’s attention and tell of any near-kin relationships or other impediments that might prevent the marriage. The possibility of someone standing in the midst of a crowd of national and international movers and shakers and announcing an impediment was somewhere between slim and none. However, the concern in the order for marriage for determining impediments continued as Dr. Hall was replaced by Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams who read the next portion.

I require and charge you both that you will answer at the dreadful day of judgment when the secrets of all hearts shall be disclosed, that if either of you know any impediment why ye may not be lawfully joined together in matrimony ye do now confess it. For be ye well assured that as many as are coupled together otherwise than God’s Word doth allow are not joined together by God, neither is their matrimony lawful.

At this point, Archbishop Williams has turned from the crowd of witnesses assembled to William and Catherine and instructed them, from their own knowledge as witnesses to their own actions, to publicly tell about any kindred relationships or other impediments to their marriage. If somehow they had been related in a way prohibited, or there was any other impediment, now was the time to make it known–it was their last opportunity. Of course, the Royal Wedding just as other weddings of our day follow historic orders simply out of tradition and not out of conviction of their truth. Even though impediments, near kin relations, and the banns were not present in the Royal Wedding to the degree of the 1549 order for marriage, they were still incorporated in the service.

Conclusion

When sickly young King Edward VI died July 6, 1553, the opportunity for posthumous revenge by Catherine of Aragon became a reality. Lady Jane Grey was presented as the next to accede to the throne and was proclaimed queen on July 9, but then on July 10, Catherine’s daughter, Mary, declared herself queen. So, two women claimed to be the Queen of England. Support for Queen Jane crumbled and Mary entered London on August 7 to begin her rule. Mary not only ruled England politically but she also re-established Roman Catholicism with a vengeance earning the ignominious name “Bloody Mary” due to her execution of Protestants.

When sickly young King Edward VI died July 6, 1553, the opportunity for posthumous revenge by Catherine of Aragon became a reality. Lady Jane Grey was presented as the next to accede to the throne and was proclaimed queen on July 9, but then on July 10, Catherine’s daughter, Mary, declared herself queen. So, two women claimed to be the Queen of England. Support for Queen Jane crumbled and Mary entered London on August 7 to begin her rule. Mary not only ruled England politically but she also re-established Roman Catholicism with a vengeance earning the ignominious name “Bloody Mary” due to her execution of Protestants.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer had contributed to the Protestant influences upon Edward VI during his reign. The Act of Uniformity of 1549 had terminated the Mass and Cranmer’s Booke of the same year had shifted England to a more Protestant worship and celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Given Cranmer’s support of Edward and his position as Archbishop of Canterbury, he was near the top of the list of those to be dealt with by Catholic Mary. Cranmer was suspended from office due to his Protestant sympathies, but he was given the opportunity to return to Catholicism or other actions would be taken. He was persuaded to and did sign a recantation of his Protestant views, but upon further reflection, he withdrew his recantation and was burned at the stake March 21, 1556. Thomas Cranmer thrust his hand that had signed the recantation into the fire first so that his offending member would be the first destroyed.

So, as the Royal Wedding itself was viewed on televisions around the world, the commentators chatted unceasingly about aesthetics, decorations, personalities, architecture, traffic routes, couturiers, the Windsors, some of the most unusual hats ever made, and other social-media trivia rather than the history and significance of the Anglican wedding ceremony and the importance of divinely instituted marriage.

Whether one is a Christian or not, a man and woman unite in marriage because it is a creation ordinance. Adam and Eve were first married and men and women have united in marriage ever since. The wedding ceremony, as Cranmer’s words stated, is performed before God. What is more, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer knew the theological importance of marriage and he ultimately died for the order of marriage included in the prayer book used then and which was used in a modified form in the Royal Wedding.

Barry Waugh

Sources–The header image is from the Westminster Abbey site and other images are available; the church provides interior pictures because photography is not allowed. The BBC has a 68 minute portion of its broadcast of the Royal Wedding available at, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-13244592. There is a lovely digital copy of Cranmer’s 1549 edition of The booke of the common prayer and administration of the Sacraments, and other rites and ceremonies of the Churche: after the use of the Churche of England available on Internet Archive . The picture of Westminster is from New Guide Westminster Abbey, 1916, and the images of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Catherine of Aragon, Mary I, Thomas Cranmer, and Anne Boleyn are from Cassels History England, Vol. 2, [1865], as in digital form on Internet Archive.