The transcription of the article, “A Belligerent D.D.,” that follows this introduction is from the Public Ledger, Memphis, Tennessee, Nov. 14, 1867. The belligerent Doctor of Divinity was Robert J. Breckinridge. The Presbyterian National Union Convention (PNUC) convened in the First Reformed Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 6, 1867. The meeting had been proposed by the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church when it met in New York in May. The commissioners were to include one minister and one ruling elder from each presbytery of each church invited. The convention included 161 commissioners from the PCUSA Old School, 64 from the PCUSA New School, twelve each representing the United Presbyterian Church and Reformed Presbyterian Church, six from the Cumberland Church, and five from the Dutch Protestant Reformed Church. The only man listed as representing the PCUS, the former Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America, was Professor Andrew D. Hepburn of the University of North Carolina who was actually in transition to a new position at Miami University in Ohio. So, the interest in uniting the Presbyterians was defined by political boundaries. It may be the case that Hepburn’s enrollment as a commissioner was intended as a perfunctory nod, or maybe even an insult.

The transcription of the article, “A Belligerent D.D.,” that follows this introduction is from the Public Ledger, Memphis, Tennessee, Nov. 14, 1867. The belligerent Doctor of Divinity was Robert J. Breckinridge. The Presbyterian National Union Convention (PNUC) convened in the First Reformed Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 6, 1867. The meeting had been proposed by the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church when it met in New York in May. The commissioners were to include one minister and one ruling elder from each presbytery of each church invited. The convention included 161 commissioners from the PCUSA Old School, 64 from the PCUSA New School, twelve each representing the United Presbyterian Church and Reformed Presbyterian Church, six from the Cumberland Church, and five from the Dutch Protestant Reformed Church. The only man listed as representing the PCUS, the former Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America, was Professor Andrew D. Hepburn of the University of North Carolina who was actually in transition to a new position at Miami University in Ohio. So, the interest in uniting the Presbyterians was defined by political boundaries. It may be the case that Hepburn’s enrollment as a commissioner was intended as a perfunctory nod, or maybe even an insult.

The story by the Public Ledger was not an in-house production but was instead borrowed from The Cincinnati Commercial. If a more comprehensive account of the PNUC is desired, the events are recorded in Presbyterian National Union Convention, Held in the City of Philadelphia, November 6th, 1867, Minutes and Phonographic Report, Philadelphia: James B. Rodgers, 1868. The PNUC did not progress smoothly and the Old School, as one might expect given that it had over sixty-percent of the commissioners, dominated the proceedings.

The comments in the following news article in brackets were included by the correspondent. There is an account of Breckinridge’s speech in Minutes, but the newspaper account below is likely more accurate. The editor of Minutes prefaced his work commenting that there were three clerks at the PNUC and problems existed in compiling the record for publication. Even though the PNUC was not a Presbyterian church court meeting, bridling his tongue and using temperate language may have helped Breckinridge persuade his listeners in the direction of his views. His grandson, B. B. Warfield (1851-1921), though pointed and direct in his writings, was a beloved professor in Princeton Seminary who does not seem to have had his grandfather’s temper.

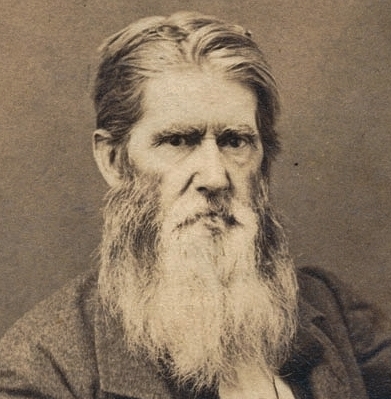

The header image of Dr. Breckinridge was provided by Director Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center.

BY BARRY WAUGH

The Rev. Dr. Eagleson (Old School), of Western Pennsylvania, moved that a committee be appointed to report a basis of union between all the branches of the Presbyterian family for consideration and adoption by them. The motion was seconded, and, being announced, was discussed at length. Dr. Breckinridge took the floor very promptly, and proceeded to say:

“I am decidedly opposed, sir, to this motion, or any effort of the kind—that is proposing any basis for organic union between these bodies. I suppose the Old School Presbyterian Church is the largest body of Presbyterians in the world, and there are sitting down here two or three offshoots from us, the New School and the Cumberland people, but I would be willing, and I suppose all of our churches and our people would be willing, to let the United, Reformed (or whatever you call it) Church prepare and give us a basis for union, provided, only, that they will do it better than we could ourselves. Now, I shall ask that brother there [referring to Dr. Eagleson] to withdraw his motion, though I know he won’t do it, for he is a Presbyterian [laughter], or I shall feel obliged to go on and make some further remarks. Will the brother withdraw his motion?”

Dr. Eagleson replied, through the chairman, that the motion was already the property of the house, and he could not, therefore, withdraw it.

Dr. Breckinridge then proceeded. “The most likely union that can be looked for, sir,” he continued, “is between our church and the other branch, as they have got now to calling it; but, sir, that union will never be consummated [sensation], for they have appointed a committee and so on. No, sir, you will not see that union if you live.” Here, Mr. Stewart, whom he was addressing, said, “I hope I shall, sir.” “Well, sir,” replied the Doctor,” I hope you’ll live a thousand years; but, take my word for it, you will never see that reunion. Not that I do not respect and love my brethren that are on that committee—those of the Old School, I mean—I don’t know anything about the others [laughter], but they won’t accomplish this. Why, sir, there isn’t appointed on the committee of our Assembly, a single man who has any reputation whatever for theological learning.”

Several members rose to call the speaker to order, and the chairman, rapping the desk with his gavel, reminded Dr. Breckinridge that personalities could not be allowed. The Doctor went on, however, along the same line for a moment, but then the chairman again called him to order. The Doctor turned somewhat wrathfully to the chairman, and continued speaking, while Mr. Stewart said: “I have as much respect for Robert J. Breckinridge as any man has, but I cannot permit these remarks on brethren known and respected.”

Dr. Breckinridge demanded to know what was the name of the brother who had called him to order. “He did not mean to offend the feelings of any one, I am responsible,” said he, “to God Almighty and to man for what I say, and I know what I am saying; and if any one doesn’t like what 1 say, he knows where I live.” [Great laughter and sensation.]

Further objection being made to the spirit of the Doctor’s remarks, the chairman again called him to order, where upon Dr. Breckinridge began to descend from the platform, saying something about not being allowed to speak. Many members cried out to him to “go on,” and the chairman most courteously begged him to remain and finish his remarks, but the Doctor, stepping back again, and said: “No, sir, I will not go on—and if you proceed to force this matter through, the curse of God will rest on you!”

The remark was received with cries of “shame!” and not a few hisses from all parts of the house, which were quickly rebuked by the chairman, who reminded the Doctor that he should remember that he was not in his own church courts, but in a general convention. “Well, sir,” said Breckinridge, “I know where 1 am—and this is the first time I ever saw a layman constituted the presiding officer of such a body. It is contrary to all law and precedent.”

With that, the Doctor left the stand and returned to his seat.