The military chaplaincy in the United States began with the presidency of George Washington. However, by the time of The Great War there were a number of non-militarily connected organizations involved in support services. For example, Roman Catholicism was not only represented by chaplains in the military but also by the Knights of Columbus. Other organizations included the mercy, relief, and medical assistance work administered by the Red Cross, as well as the interdenominational Young Men’s Christian Association, YMCA. Even though the YMCA is known currently for its physical fitness and calorie burning facilities, it was founded in 1844 by George Williams in London, England, for the purpose of providing Bible studies and family-like influences for young men relocating to cities for employment. In the early twentieth century the YMCA was a highly influential interdenominational organization with facilities in numerous cities and student organizations on many college and university campuses. When the United States mobilized to enter the war in April 1917, the YMCA kicked into high gear to support the troops. One of those who chose to serve with the YMCA was J. Gresham Machen.

The military chaplaincy in the United States began with the presidency of George Washington. However, by the time of The Great War there were a number of non-militarily connected organizations involved in support services. For example, Roman Catholicism was not only represented by chaplains in the military but also by the Knights of Columbus. Other organizations included the mercy, relief, and medical assistance work administered by the Red Cross, as well as the interdenominational Young Men’s Christian Association, YMCA. Even though the YMCA is known currently for its physical fitness and calorie burning facilities, it was founded in 1844 by George Williams in London, England, for the purpose of providing Bible studies and family-like influences for young men relocating to cities for employment. In the early twentieth century the YMCA was a highly influential interdenominational organization with facilities in numerous cities and student organizations on many college and university campuses. When the United States mobilized to enter the war in April 1917, the YMCA kicked into high gear to support the troops. One of those who chose to serve with the YMCA was J. Gresham Machen.

John Gresham Machen was born July 28, 1881 in Baltimore, Maryland to Arthur Webster and Mary (Minnie) Gresham Machen. His father was a highly-respected attorney and his homemaker mother from Macon, Georgia, did some writing including a book titled, The Bible in Browning. The Machens faithfully—with Gresham and his two brothers—attended the Franklin Street Presbyterian Church in Baltimore. When he went to college he earned his undergraduate degree from Johns Hopkins University, 1901, and then continued as a graduate student, 1901-2. For his theological studies he attended Princeton Theological Seminary where he received the BD in 1905 while also studying in Princeton University to earn a MA in 1904. Following studies in Germany he returned to Princeton Seminary to teach New Testament first as an instructor, 1906-14, and then as an assistant professor of New Testament. In 1929 he resigned from Princeton and founded, along with some of his Princeton colleagues, Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. In 1936, Dr. Machen was the leader of those who founded what would later be named the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. While on a speaking trip in Bismarck, North Dakota, J. Gresham Machen died of pneumonia on January 1, 1937.

In a way, the beginning of The Great War would be anticlimactic for Machen because on June 23, 1914, just five days before Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassinated, he had been ordained for the ministry after his own personal conflict about ordination. But as the war developed he became increasingly interested in the nations involved and the concerns at stake. By August there was increasing participation in the war because Germany declared war on Russia and France, and Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia, and then late in the month Japan declared war on Germany. The number of countries participating in the war was increasing, but President Woodrow Wilson was determined that the United States would maintain neutrality despite a growing number of casualties from his non-combatant citizens.

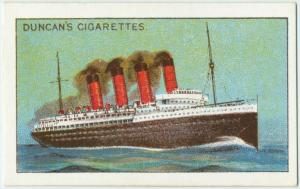

As the war raged in many parts of the world, J. G. Machen was inaugurated an assistant professor at Princeton Seminary on May 3, 1915, which was just four days before the Lusitania would be sunk by a German U-Boat. The sinking of the Lusitania with 128 United States citizens included among the dead increased the calls for the United States to enter the war, but it would take nearly two more years of conflict incidents before President Wilson would declare war. There were more German acts of violence against the United States including the sabotage of a munitions plant in Delaware, unrestricted submarine warfare by the Germans resulting in the sinking of United States ships, Germany’s attempt to encourage Mexico to invade Texas, and other incidents that contributed to Woodrow Wilson asking Congress for a declaration of war which was announced on April 6, 1917.

As the war raged in many parts of the world, J. G. Machen was inaugurated an assistant professor at Princeton Seminary on May 3, 1915, which was just four days before the Lusitania would be sunk by a German U-Boat. The sinking of the Lusitania with 128 United States citizens included among the dead increased the calls for the United States to enter the war, but it would take nearly two more years of conflict incidents before President Wilson would declare war. There were more German acts of violence against the United States including the sabotage of a munitions plant in Delaware, unrestricted submarine warfare by the Germans resulting in the sinking of United States ships, Germany’s attempt to encourage Mexico to invade Texas, and other incidents that contributed to Woodrow Wilson asking Congress for a declaration of war which was announced on April 6, 1917.

As with so many Americans, J. Gresham Machen wanted to help with the war effort but he wanted to do so as a non-combatant. After considering a Presbyterian Church chaplaincy, then rejecting driving an ambulance because they were sometimes used to haul munitions, Machen decided to work with the YMCA. It was not an ideal situation and he had some reservations about the organization, but he hoped to have the opportunity to teach the Bible and minister to the soldiers while he performed whatever duty he was assigned.

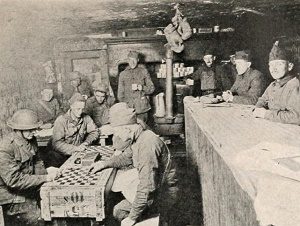

After his training, Rev. Machen boarded ship and headed for France in January 1918. He was initially assigned to be a secretary of a YMCA hut in a cooperative work with a French secretary. The huts provided places for soldiers to relax, write letters, play games, and participate in sports activities. Instead of leading students in seminary through recitations of Greek paradigms, he would instead be serving hot chocolate while selling tobacco products, candies, shaving gear, and snacks to the soldiers. Even though he operated a rest facility for the soldiers, he commented that “there is little rest about it—especially for the Y.M.C.A. men.” Contributing to the lack of down time were frequent alarms for chemical gas attacks at night, to which were added aircraft flying overhead with their loud engines. Sleep, when it could be obtained, was limited to three or four hours each night. He commented further that war life was communal and there was no privacy for anyone. His extended periods of idleness changed into harried and busy days that often stretched from dawn until after nine o’clock at night as the business in his canteen increased.

After his training, Rev. Machen boarded ship and headed for France in January 1918. He was initially assigned to be a secretary of a YMCA hut in a cooperative work with a French secretary. The huts provided places for soldiers to relax, write letters, play games, and participate in sports activities. Instead of leading students in seminary through recitations of Greek paradigms, he would instead be serving hot chocolate while selling tobacco products, candies, shaving gear, and snacks to the soldiers. Even though he operated a rest facility for the soldiers, he commented that “there is little rest about it—especially for the Y.M.C.A. men.” Contributing to the lack of down time were frequent alarms for chemical gas attacks at night, to which were added aircraft flying overhead with their loud engines. Sleep, when it could be obtained, was limited to three or four hours each night. He commented further that war life was communal and there was no privacy for anyone. His extended periods of idleness changed into harried and busy days that often stretched from dawn until after nine o’clock at night as the business in his canteen increased.

As his busy-ness increased so did the dangers associated with his proximity to the front. At one point, he was so close to the advancing enemy that he had to withdraw across a bridge to avoid being trapped in enemy territory—the Germans were near and if they managed to detonate the bridge he would not be able to cross the river. Sometimes ordnance fell close enough to the Princeton professor that he had to dive into shell craters or descend into wet, debris-filled cellars for protection. He had to live continuously in his wet, dirty, wool clothing with limited opportunities to bathe or shave. Some correspondents during the war commented on how bedraggled and unkempt the soldiers appeared, but soldiers did not have the luxury of yielding to the waning influence of the Victorian emphasis on propriety and appearance. As his experience of the horrors of war continued, he described the situation in a letter to his mother saying, “Existence over here is so desperately lonely that it is a comfort to know someone cares.” True to his concern for Scripture and its teaching, he was often frustrated by the great indifference shown by the military to worship and the gospel; he sometimes held Bible studies with as few as two others in attendance.

As his busy-ness increased so did the dangers associated with his proximity to the front. At one point, he was so close to the advancing enemy that he had to withdraw across a bridge to avoid being trapped in enemy territory—the Germans were near and if they managed to detonate the bridge he would not be able to cross the river. Sometimes ordnance fell close enough to the Princeton professor that he had to dive into shell craters or descend into wet, debris-filled cellars for protection. He had to live continuously in his wet, dirty, wool clothing with limited opportunities to bathe or shave. Some correspondents during the war commented on how bedraggled and unkempt the soldiers appeared, but soldiers did not have the luxury of yielding to the waning influence of the Victorian emphasis on propriety and appearance. As his experience of the horrors of war continued, he described the situation in a letter to his mother saying, “Existence over here is so desperately lonely that it is a comfort to know someone cares.” True to his concern for Scripture and its teaching, he was often frustrated by the great indifference shown by the military to worship and the gospel; he sometimes held Bible studies with as few as two others in attendance.

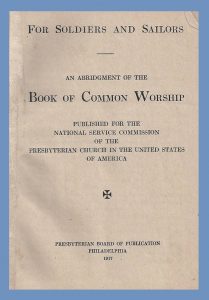

As the Great War neared its end, Dr. Machen surveyed the field following one battle and described the scene of destruction and desolation in pallid grays much like the scenes that would give many a sense of the horror of war in the cinematic production of All Quiet on the Western Front. As the last few days of the war passed, Machen assumed the duties of a stretcher-bearer carrying many mutilated dead and wounded from the field. At this point he may have remembered the prayer for after a battle published in the Presbyterian Church’s book, For Soldiers and Sailors: An Abridgement of the Book of Common Worship.

Almighty God, who in Thy mercy hast covered our heads in the day of battle and saved us from the hands of our enemies; we give Thee remembrance and grateful thanks, and we give our lives anew to Thy service. Because Thou hast been our help, therefore in the shadow of Thy wings will we rejoice. Because Thou hast delivered our souls from death, we will walk before Thee in the land of the living. Continue to us Thy protection, we beseech Thee, and strengthen our trust in Thee as our God and Father in Christ Jesus. Encourage our hearts as we go forward; crown our arms with speedy and decisive victory: and give to the world the blessing of an honorable and lasting peace. For Christ’s sake. Amen.

Almighty God, who in Thy mercy hast covered our heads in the day of battle and saved us from the hands of our enemies; we give Thee remembrance and grateful thanks, and we give our lives anew to Thy service. Because Thou hast been our help, therefore in the shadow of Thy wings will we rejoice. Because Thou hast delivered our souls from death, we will walk before Thee in the land of the living. Continue to us Thy protection, we beseech Thee, and strengthen our trust in Thee as our God and Father in Christ Jesus. Encourage our hearts as we go forward; crown our arms with speedy and decisive victory: and give to the world the blessing of an honorable and lasting peace. For Christ’s sake. Amen.

The war for Machen was, as for so many of the troops and supporting forces, a life-changing event. The Baltimore-born gentleman and scholar had his perspective adjusted by his war experience. He saw the horrible sights and smelled the lingering odor of burnt gunpowder. He experienced the deafening explosive concussions and heard the screams of the wounded and dying. Fear of a chemical gas attack was ever present. The mutilated and dismembered corpses produced by incessant shelling and dense, flesh-shredding machinegun fire deeply saddened him. Even though J. Gresham Machen’s YMCA job was described as non-combatant work, he did experience a small sample of some of the dangers that befell the combatants in the trenches.

Following a trip to rest in his family’s cottage in Seal Harbor, Dr. Machen returned to Princeton Seminary and his duties teaching, but what had been routine before the war was viewed after it with a greater sense of his place in God’s purpose. Before the war Machen had been a studious academic, preacher, and dedicated Christian, but after the war he continued in his calling with a deeper sense of the breadth of what being Christian meant. For example, before the war he had been financially assisting a man named Richard Hodges who had become a Christian but continued to struggle with a reoccurring temptation for alcohol. Before the war, Machen sometimes expressed frustration about how much time he was spending in assisting Hodges because it was keeping him from his studies. After the war he continued to work hard but his labor was tempered by a sense of the need to apply the Bible he studied and taught. Machen’s attitude towards Hodges and his characteristically alcoholic behavior changed following his war experience.

A good many people might think Hodges not worth working for—there is deceitfulness in him as well as his recurrent weakness—but in the providence of God I have been given absolute responsibility (so far as anyone has it) for the welfare of a human soul, and I cannot put the matter out of my mind. Meanwhile my academic work has absolutely gone by the board.

The scholar was still concerned about his studies but now he grasped more fully his responsibility to Richard Hodges; it was not only providential that Machen enjoyed great intellectual abilities but also that God had placed Mr. Hodges along the path of his life. Machen’s ministry to Hodges was now a privilege and a responsibility, while before the war, he saw the aging alcoholic more as a distraction and a responsibility. Several years after these comments to his mother, Machen wrote in “The Claims of Love” that “service is comparatively useless unless it comes from the heart; true service is not a substitute for love, but the expression of love”—could it be that he was thinking of his war-changed perspective on Hodges when he penned these words? As 1921 was drawing to its end, Machen was honored for his service during World War I with the “médaille commémorative de la guerre” by the War Office of France for serving more than six months in the combat zone.

If you are interested in reading more about J. Gresham Machen, the biography by his good friend and seminary colleague, Ned B. Stonehouse, J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Memoir, provides a personal and informed perspective with considerable use of Machen’s correspondence and is available from the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. The standard scholarly but engagingly written book for biographical information with an emphasis on his work during the religious controversies of the 1920s is D. G. Hart’s Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America. If you want less detail and an easier but not simplistic read, including illustrations, see Stephen J. Nichols’s J. Gresham Machen: A Guided Tour of His Life and Thought. For more about Machen and the war see his collection of letters written home, edited by this site’s author, and published in Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I, and for more about his ministry to Richard Hodges see the author of this site’s article, “Mr. Machen’s Protégé,” which was published in the Westminster Theological Journal, vol. 71, 2009, pages 21-51. Biographies on Presbyterians of the Past regarding some of Machen’s family include one for his cousin, LeRoy Gresham, and another for his maternal grandfather, John Jones Gresham. For a history of the YMCA work in World War I, see the set of books edited by former President William Howard Taft and Frederick Harris, Service With Fighting Men. An Account of the Work of the American Young Men’s Christian Associations in the World War, 2 vols., 1922.

BY BARRY WAUGH

Sources–The two images of YMCA huts are from Katherine Mayo’s book, That Dxxx Y, New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1920, as digitized on Internet Archive. Neither of the images are of Machen’s hut, but the battlefield hut image with the checkers and counter would be closest to his first hut, and the second image may be like a later hut he operated. The cigarette card image, date unknown, of the Lusitania is from the Digital Collection of the New York Public Library; cigarette cards were promotional items included in packs of cigarettes like a sports card with bubblegum (Do they do that anymore?). The image of the first page of Psalms is from The Holy Bible, 1595, as on Internet Archive.