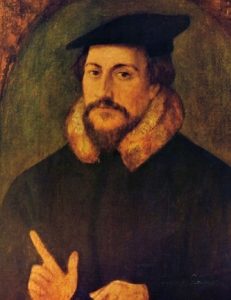

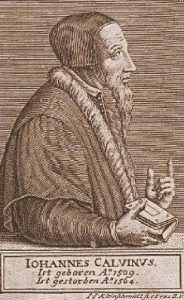

Jean (John) was born July 10, 1509, to Gérard and Jeanne Lefranc Cauvin (Calvin) in Noyon, France. Noyon is about sixty miles northeast of Paris and at the time its cathedral was the seat of the bishop of Noyon, Charles de Hangest. Gérard was a legal advisor to the cathedral and served in other administrative capacities. John’s mother died when he was young and his father remarried, but he did not get along well with his stepmother. Calvin obtained his early schooling privately in the home of the Lord of Montmor, who was the brother of Bishop Charles de Hangest. It was Gérard’s desire that John become a priest and his education was planned for that end. With Calvin’s schooling in the home of a lord came training in nobility, deportment, and the ways of a gentleman. The portrait shows dapper gentleman Jean Cauvin ready for the day with his precisely trimmed beard, a fur collar, and a smart beret.

Jean (John) was born July 10, 1509, to Gérard and Jeanne Lefranc Cauvin (Calvin) in Noyon, France. Noyon is about sixty miles northeast of Paris and at the time its cathedral was the seat of the bishop of Noyon, Charles de Hangest. Gérard was a legal advisor to the cathedral and served in other administrative capacities. John’s mother died when he was young and his father remarried, but he did not get along well with his stepmother. Calvin obtained his early schooling privately in the home of the Lord of Montmor, who was the brother of Bishop Charles de Hangest. It was Gérard’s desire that John become a priest and his education was planned for that end. With Calvin’s schooling in the home of a lord came training in nobility, deportment, and the ways of a gentleman. The portrait shows dapper gentleman Jean Cauvin ready for the day with his precisely trimmed beard, a fur collar, and a smart beret.

In 1523 fourteen-year-old John moved to Paris to study for the priesthood. Education was in transition in Europe because of the Renaissance stress on studying the works of antiquity, particularly classics of the Greeks and Romans. Included among ancient writings is God’s revealed will in the Bible; the Renaissance emphasis on going to the sources, ad fontes, provided the interpretive tools for studying Scripture from the original Greek and Hebrew texts. In Paris, the writings of Martin Luther were influencing students, but his works were officially banned by the church. One follower of Luther, Jean Vallière, was burned at the stake not long before young Calvin arrived. When the Renaissance method of appealing to the sources was applied to sola Scriptura by reformers, it faced opposition because all things theological were controlled by the papacy. Thus, the educational environment regarding theological subjects was tense when Calvin began studies in Paris. He started in the Collège de la Marche but in short order moved to the more respected Collège de Montaigu where he completed both the bachelor’s and master’s degrees by 1528. He was progressing well along the educational track to become a priest until his father changed his mind regarding John’s future. Gérard decided that the prospects for his son making a good income were greater in the practice of law than the priesthood, so Calvin was redirected to the study of law.

Calvin moved about eighty miles south of Paris to Orleans for his law program, but when his father died in 1531 his interest turned to independent studies. Though for a time staying the course with law, he increasingly devoted himself to Scripture and the writings of the church fathers, particularly Augustine. While in Orleans he had contact with his cousin Pierre Robert, called Olivétan, who influenced Calvin greatly regarding the Reformation. Olivétan himself would in a few years make an important contribution to reform by providing the first French translation of the Bible from the original Greek and Hebrew ever published. John was encouraged by his cousin to devote himself to studying the original languages of Scripture, and it is believed that Olivétan was an important instrument used by God for Calvin’s conversion. The exact point in time when Calvin embraced the gospel is not certain, but it is thought to have been sometime around 1532. Several years later Calvin commented in the preface to his Psalms commentary that his conversion had affected his studies.

Calvin moved about eighty miles south of Paris to Orleans for his law program, but when his father died in 1531 his interest turned to independent studies. Though for a time staying the course with law, he increasingly devoted himself to Scripture and the writings of the church fathers, particularly Augustine. While in Orleans he had contact with his cousin Pierre Robert, called Olivétan, who influenced Calvin greatly regarding the Reformation. Olivétan himself would in a few years make an important contribution to reform by providing the first French translation of the Bible from the original Greek and Hebrew ever published. John was encouraged by his cousin to devote himself to studying the original languages of Scripture, and it is believed that Olivétan was an important instrument used by God for Calvin’s conversion. The exact point in time when Calvin embraced the gospel is not certain, but it is thought to have been sometime around 1532. Several years later Calvin commented in the preface to his Psalms commentary that his conversion had affected his studies.

To the study of law I endeavored faithfully to apply myself, in obedience to the will of my father; but God, by the secret guidance of his providence, at length gave a different direction to my course.…God by a sudden conversion subdued and brought my mind to a teachable condition, which was more hardened in such matters than might have been expected of one at my young age. Having thus received some taste and knowledge of true godliness, I was immediately inflamed with so intense a desire to make progress therein, that although I did not altogether leave off other studies, I yet pursued them with less ardor. (xl-xli)

The king of France, Francis I, had ruled since 1515 and Luther’s theses were posted less than two years into his reign. When Francis died in 1547 he left a legacy of many decisions regarding Protestants. A pivotal event that occurred in France in October 1534 was the “Affair of the Placards.” Posters attacking the mass and calling it witchcraft were posted on walls all over Paris as well as in other major cities. One was even posted on the door of King Francis’s bedroom. The king had been tolerant towards the Reformation and had even hoped peace could be achieved between Protestants and Catholics, however the placard incident was interpreted as a personal attack. Francis switched from toleration to persecution and repression. Some Protestants were abused, imprisoned, and several were executed as the placards incident brought subjugation. Many Protestants fled France for refuge in other realms.

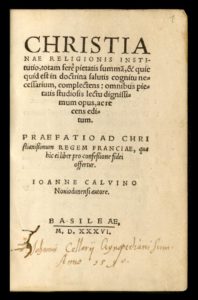

Young Calvin was one of those who fled to escape persecution and continue his work in a location friendlier to reforming ideas. Travelling with an associate, Louis du Tillet, they arrived in Basel early in 1535. Calvin was broke at the time so the wealth of Louis came in handy for paying expenses. The language of the city was German, which Calvin did not know, so he laid low with other French exiles in town and adopted the name Martinus Lucianus. The solitude was really a golden opportunity for him to learn more about the Bible and compose writings from his studies. During the Basel exile he wrote the first edition of Institutes of the Christian Religion and the preface to the French Bible published by Olivétan in 1535. Calvin left Basel for Ferrara, Italy, the spring of 1536, where he met with some individuals interested in reforming the church. One person, the Duchess of Ferrara, Reneé of France, was drawn to Reformation theology but due to her position as a member of the nobility, she tried to maintain the appearance of a faithful Catholic while hoping for reform. Becoming a Protestant was often a dangerous decision for anyone, but could be especially so for nobility.

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) invited John Calvin to Geneva in 1536. The church sorely needed guidance and leadership. Calvin was first described in Geneva civil records as a “lecturer in holy Scripture.” Early in 1537 his collection of articles composed to govern the church of Geneva were presented. Included were instructions concerning the practice of the Lord’s supper and the associated use of excommunication. Other articles included the importance of instructing children, the need for elders, the importance of singing Psalms, and a twenty-one-article confession of faith that all who joined the church had to affirm. Calvin, Farel, and other pastors believed that one could not take the Lord’s Supper without affirming the confession of faith, but the Geneva government disagreed and said all should be able to partake regardless. This tension between the state and the church led to the government ordering Calvin and Farel to leave Geneva in April 1538. The history of the church sometimes shows confusion of church and state, which is exemplified here by the council’s ejection of ministers; when the state and church come into conflict, it is often the state that wins as it wields its sword against the church.

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) invited John Calvin to Geneva in 1536. The church sorely needed guidance and leadership. Calvin was first described in Geneva civil records as a “lecturer in holy Scripture.” Early in 1537 his collection of articles composed to govern the church of Geneva were presented. Included were instructions concerning the practice of the Lord’s supper and the associated use of excommunication. Other articles included the importance of instructing children, the need for elders, the importance of singing Psalms, and a twenty-one-article confession of faith that all who joined the church had to affirm. Calvin, Farel, and other pastors believed that one could not take the Lord’s Supper without affirming the confession of faith, but the Geneva government disagreed and said all should be able to partake regardless. This tension between the state and the church led to the government ordering Calvin and Farel to leave Geneva in April 1538. The history of the church sometimes shows confusion of church and state, which is exemplified here by the council’s ejection of ministers; when the state and church come into conflict, it is often the state that wins as it wields its sword against the church.

Calvin needed to find another place to minister and his first choice was Basel, but a group in Strasbourg under the leadership of Martin Bucer (1491-1551) brought him to their city. Calvin delivered his first sermon as a refugee preacher September 8, 1838. Bucer was senior to Calvin by almost twenty years making for an influence that was much like a father to his son. Bucer had difficulty communicating his ideas clearly and succinctly in writing, so Calvin was able to take his teaching and present it cogently in writing. Martin Luther said of one of Bucer’s works that the “whole thing is too long … I could tell right away that Bucer, the chatterbox, was at work here.” The gift of gab is not an attribute when one writes sometimes complex concepts for precise communication. While in Strasbourg, Calvin married Idelette de Bure who was widowed when her husband died of the plague. She had several children that Calvin adopted as his own. During his three years in Strasbourg the political situation in Geneva changed resulting in Farel imploring him to return, but Calvin did not want to go. However, in the fall of 1540 he gave in saying, “If I had any choice I would rather do anything than give in to you in this matter, but since I remember that I no longer belong to myself, I offer my heart to God as a sacrifice.”

Just a month after his reticent return to Geneva, John Calvin’s ecclesiastical ordinances were adopted by the city government. Included in the document were four church offices—pastor, teacher (or doctor), elder, and deacon. Calvin and the pastors would at times experience a difficult relationship with the councils as the ordinances and other aspects of the church were applied. The government wanted to retain control over the church and its practices, but Calvin believed in the particularly Pauline principle that the state’s ministry is to wield the sword to punish evil doers and protect its citizens, but the church’s ministry is to preach the gospel and apply its grace and discipline spiritually. Calvin and his company of pastors sometimes found themselves differing with the Geneva government regarding issues of leadership and authority.

In April 1549, Pastor Calvin suffered an immeasurable loss. His wife of less than a decade, Idelette, died from an extended illness. Calvin was a man who rarely said anything about his personal life but in this case he confided to mentor and friend Pierre Viret regarding the great loss caused by her passing.

In April 1549, Pastor Calvin suffered an immeasurable loss. His wife of less than a decade, Idelette, died from an extended illness. Calvin was a man who rarely said anything about his personal life but in this case he confided to mentor and friend Pierre Viret regarding the great loss caused by her passing.

Although the death of my wife has been exceedingly painful to me, I subdue my grief as well as I can.… I have been bereaved of the best companion of my life, of one who shared my poverty, but also, if it had been so ordered, would have joined me in death. During her life she was the faithful helper of my ministry. From her I never experienced the slightest hindrance. She was never a burden to me throughout the entire course of her illness.

And to his mentor and friend Guillaume Farel, Calvin also expressed his sorrow.

Intelligence of my wife’s death has perhaps reached you before now. I do what I can to keep myself from being overwhelmed with grief. My friends also leave nothing undone that may administer relief to my mental suffering.… I at present control my sorrow so that my duties may not be interfered with.

A true expression of love and loss by a man who is sometimes described unjustly by social and political historians as a callous and doctrinaire tyrant that hated women. Earlier in their marriage, Idelette had given birth to a child named Jacques, but he died just a few days later. Calvin did not remarry.

Calvin’s ministry in Geneva was not an easy one because he suffered persecution and insults from some citizens. Sometimes one faction would become appeased, then another more virulent one would arise to take its place. He even was a target of biological warfare. In his letters he commented that someone had left what appeared to be bodily fluid on the door handle of his home during the plague with the intention of infecting him. Some unhappy residents of Geneva chose to name their dogs, cows, or other animals “Calvin” as insults. There were also problems during worship. One man took his hunting firearm and dog to church so he could quickly stalk his prey after the service. During a Lord’s Supper service one mentally disturbed woman barked like a dog. A woman used a stool as a weapon to severely injure another woman during an argument over seating in the church, and one woman insisted on sitting near a particular man because she believed God had told her that she would marry him (men and women sat apart in worship in the era). It was not uncommon for congregants to snore loudly, hold conversations, or pass around food during services. Maybe preachers today should be grateful for their attentive, or at least apparently attentive, flocks during the delivery of their sermons.

John Calvin died in 1564 at the age of fifty-four. He was a broken, sickly, and worn out man, as can be seen in his portrait. He suffered from kidney stones, stomach troubles, reoccurring bouts with fever, and constipation, all of which were exacerbated by superstitious remedies and a poorly balanced fat-filled diet. Paris doctors recommended that he ride a horse to help break up and dislodge his kidney stones—the pain must have been excruciating. Theodore Beza, his good friend and biographer, notes that Calvin stipulated he was to be buried in an unmarked grave because he feared his burial site might become an idol as a place of pilgrimage.

John Calvin died in 1564 at the age of fifty-four. He was a broken, sickly, and worn out man, as can be seen in his portrait. He suffered from kidney stones, stomach troubles, reoccurring bouts with fever, and constipation, all of which were exacerbated by superstitious remedies and a poorly balanced fat-filled diet. Paris doctors recommended that he ride a horse to help break up and dislodge his kidney stones—the pain must have been excruciating. Theodore Beza, his good friend and biographer, notes that Calvin stipulated he was to be buried in an unmarked grave because he feared his burial site might become an idol as a place of pilgrimage.

Calvin’s legacy is immense. Much of his teaching became the cornerstone of Reformed theology. Even the United States can trace the organization of its national government to Calvin’s concern for separating church and state. He wrote commentaries on the Bible for much of the New Testament and a considerable portion of the Old, and added to these are innumerable sermons many of which are yet to be translated. Many of his letters have been published in English. His Institutes of the Christian Religion came out in several editions from 1536 to 1560 in either Latin or French, but it was first published in English as translated by Thomas Cranmer’s son in law, Thomas Norton, in 1562. Calvin did not personally publish his sermons, but they were copied by a stenographer as delivered and then compiled for posterity.

On a personal note, whenever I read anything by Calvin I find myself nodding my head in affirmation as I read a particularly helpful comment. The breadth and depth of his knowledge included not only theology, ecclesiology, Bible, and ministry, but also science, politics, world affairs, law, and just about any subject that could be studied in the day. It is incredible how any man, no matter how intellectually gifted, could possibly accomplish all that John Calvin did, but he did it. If the effort is made, the reward from reading Calvin can be considerable. God in his providence has often provided leadership for his church via sprinkling prolific individuals throughout history who produced written wisdom for successive generations, one of those individuals was John Calvin.

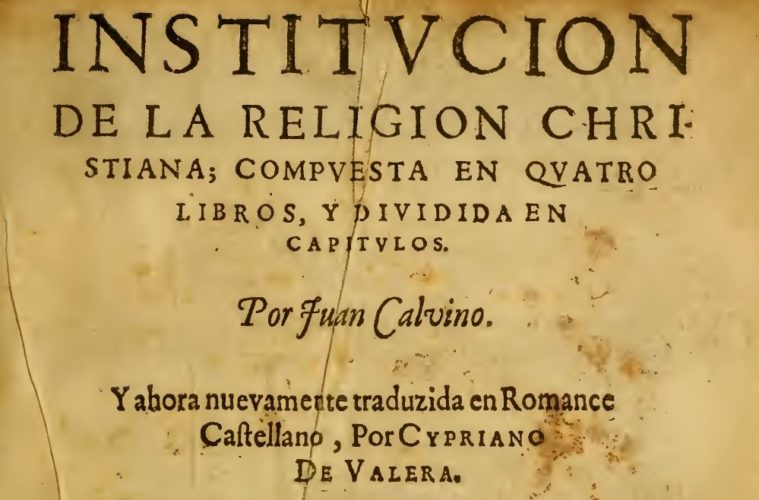

The header shows the title page of Institutes of the Christian Religion in Spanish as translated by Cypriano de Valera in 1597. It is often forgotten that there were and are Protestants in Spain because oppression by the papacy was so effective as exemplified by Valera having to flee to England, then Holland to continue his work. In 1602, de Valera published the Reina-Valera Bible which can be viewed in its second edition on the website of the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC. The description on the Museum of the Bible website says, “In the 1580s, de Valera began revising Casiodoro de Reina’s Bible of 1569, the first complete Spanish translation of the Old Testament, Apocrypha, and New Testament.” The Reina-Valera is to Spanish speakers as the King James Version is to English speakers; both these Bibles continue in print. The copy of the Reina-Valera Bible that the Museum of the Bible has was owned by Maria Cristina (1806-1878), Queen of Spain.

Barry Waugh

Notes—There are differences of opinion regarding aspects of Calvin’s life and I found accounts of his college studies conflicting. Also, several biographers commented that the reason Calvin left theology for law was because his father had a falling out with the church and he wanted his son to abandon pursuing the priesthood. However, Calvin’s introduction to his Psalms commentary mentions that his father wanted him to make more money as a lawyer. If you read French you will find there are many books available about Calvin; he was French and highly important for the Huguenots or French Reformed Church. The title page image of Calvin’s 1536 Institutes is from the University of Basel Library. The image of the memorial in Geneva includes, left to right, Guillaume Farel, John Calvin, Theodore Beza, and John Knox. Regarding Calvin’s health see The Medical History of the Reformers: Luther, Calvin, and Knox, by John Wilkinson, M.D., forward by David F. Wright, Edinburgh, 2001. The letters quoted are available in the Jules Bonnet collection of Calvin’s letters published in the 1850s and reprinted since. Theodore Beza’s brief biography The Life of John Calvin Carefully Written by Theodore Beza Minister of the Church of Geneva was translated into English by Henry Beveridge, published by the Calvin Translation Society in 1844, and it has been reprinted often over the years. A very good biography of Calvin is Robert Godfrey’s John Calvin: Pilgrim and Pastor, Crossway, 2009, which targets a more general readership (i.e. it reads well and does not get bogged down in subjects of academic interest). Available in PDF on Presbyterians of the Past is Thomas C. Johnson’s John Calvin and the Genevan Reformation: A Sketch, Richmond, 1900. An old but good title is Jean Cadier’s, The Man God Mastered, which is an English translation of the French edition. The information about problems during worship in Geneva is from a book reviewed on Presbyterians of the Past—Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609, by S. M. Manetsch, Oxford, 2013. Luther’s comment about Bucer the “chatterbox” is from page 190 of Martin Greschat’s book, Martin Bucer: A Reformer and His Times, 1990, which was translated from the German by Stephen E. Buckwalter for publication by Westminster-John Knox Press in 2004; Greschat said that Bucer “had always lacked an ability to formulate things briefly, to simplify his written trains of thought, and especially to bring matters to a point” (p. 188).