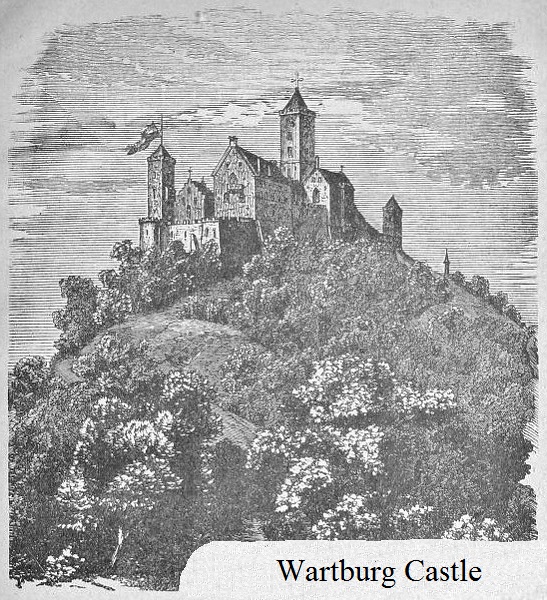

A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing; our helper he amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing are the familiar opening words written by Martin Luther in his great hymn, A Mighty Fortress. It was composed in 1527, which was a particularly difficult year for the Luther household because both Martin and his one-year-old son, Hans, suffered but survived extended illnesses, then when the plague visited town the Luthers opened their home as a hospital. Making it through the challenging year may have reminded Luther of God’s faithfulness in the past when Frederick the Wise hid him in Wartburg Castle in 1521. Luther found the immense fortification to be a bulwark against agents of Emperor Charles V who were looking to arrest him for heresy. Ein’ Feste Berg, the German title, was not Luther’s first nor only hymn. His first composition was A New Song Shall Here Be Begun, which he authored in memory of three Augustinian monks burned at the stake in Antwerp on July 1, 1523. The three were executed for failure to renounce their Protestant beliefs which they had learned primarily from Luther’s writings. In total, Luther composed thirty-eight hymns six of which are included in the Trinity Hymnal, Revised (red cover) used by many Presbyterian congregations. Martin Luther said of music that it “has the natural power of stimulating and arousing the souls of men.”

A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing; our helper he amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing are the familiar opening words written by Martin Luther in his great hymn, A Mighty Fortress. It was composed in 1527, which was a particularly difficult year for the Luther household because both Martin and his one-year-old son, Hans, suffered but survived extended illnesses, then when the plague visited town the Luthers opened their home as a hospital. Making it through the challenging year may have reminded Luther of God’s faithfulness in the past when Frederick the Wise hid him in Wartburg Castle in 1521. Luther found the immense fortification to be a bulwark against agents of Emperor Charles V who were looking to arrest him for heresy. Ein’ Feste Berg, the German title, was not Luther’s first nor only hymn. His first composition was A New Song Shall Here Be Begun, which he authored in memory of three Augustinian monks burned at the stake in Antwerp on July 1, 1523. The three were executed for failure to renounce their Protestant beliefs which they had learned primarily from Luther’s writings. In total, Luther composed thirty-eight hymns six of which are included in the Trinity Hymnal, Revised (red cover) used by many Presbyterian congregations. Martin Luther said of music that it “has the natural power of stimulating and arousing the souls of men.”

Martin Luther’s reforming work in Germany shows the great interest he had in the Bible’s book of Psalms. A Mighty Fortress is based on Psalm 46, his works published in English include five volumes of selected commentaries on the Psalms, and Psalms were often the passages used for his sermons, however, Luther did not believe the Psalms nor the entire Bible contained the only appropriate words for singing in worship. But moving from the German to the French-speaking branch of the Reformation under the leadership of John Calvin, congregational singing was also an important part of worship but the words used were limited to Scripture, almost exclusively from the book of Psalms, and they were sung a capella.

John Calvin and Martin Luther differed regarding what constituted appropriate verbal content for singing in worship, but one thing they agreed upon was an appreciation for Psalm 46. One of Calvin’s nine Psalms adapted for worship is the forty-sixth, so maybe the fortress struck both reformers as the best illustration of God’s care for his sheep, much like Jesus securing his sheep in the sheepcote in John 10. In the sixteenth century the most substantial and intimidating structure for a secure home was a stone-fortified castle on the highest ground. In addition to his use of Psalms for singing, Calvin also adapted the Ten Commandments and the Song of Simeon (Luke 2:29-32). It is believed that the hymn I Greet Thee, Who My Sure Redeemer Art was written by Calvin. It may seem that I Greet Thee contradicts Calvin’s exclusive use of Scripture for singing in worship, but in more casual contexts outside of worship he believed the singing of hymns was acceptable.

Even though Calvin wrote metrical versions of some Psalms and passages of Scripture, he preferred to have musicians working with him adapting additional Psalms and composing music. One of his musicians was Clément Marot who translated several Psalms and composed music for both the Strasbourg and Geneva Psalters. Another contributor to the Geneva Psalter was Louis Bourgeois who composed three of the hymns used in The Trinity Hymnal, Revised. The first selection, All People That On Earth Do Dwell, was authored by William Kethe in English with music originally composed by Bourgeois for the Geneva Psalter.

The Reformation of worship in Geneva was an application of sola Scriptura to the verbal content of musical praise to God. Roman Catholicism almost exclusively used choirs or choruses singing in Latin during Mass, so the idea that worshippers could sing in their native language must have been unsettling or even intimidating to congregations influenced by the Reformation whether they gathered in Luther’s Wittenberg or Calvin’s Geneva. As with so many aspects of Christian worship that were changed by the Reformation, worship in song had not been done that way for centuries. Calvin found himself with a problem getting people to sing but he figured out a solution—the children of the church. The children were taught the tunes used with the Psalms, so just as they memorized their catechism they also memorized the words of the Psalms. One can imagine some of the children at home singing the Psalms while doing their chores or when they were involved in other activities. If the children could learn to sing in worship, then so could their parents, grandparents, and other family members.

The Reformation of worship in Geneva was an application of sola Scriptura to the verbal content of musical praise to God. Roman Catholicism almost exclusively used choirs or choruses singing in Latin during Mass, so the idea that worshippers could sing in their native language must have been unsettling or even intimidating to congregations influenced by the Reformation whether they gathered in Luther’s Wittenberg or Calvin’s Geneva. As with so many aspects of Christian worship that were changed by the Reformation, worship in song had not been done that way for centuries. Calvin found himself with a problem getting people to sing but he figured out a solution—the children of the church. The children were taught the tunes used with the Psalms, so just as they memorized their catechism they also memorized the words of the Psalms. One can imagine some of the children at home singing the Psalms while doing their chores or when they were involved in other activities. If the children could learn to sing in worship, then so could their parents, grandparents, and other family members.

Today, congregational singing is an integral part of Protestant worship. Now five-hundred years since Martin Luther posted his theses and nearly as many years since the Genevan Psalter, many Psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs have been added to the church music library. The importance of sola Scriptura for singing in worship is shown in the Trinity Hymnal, Revised, which includes ninety-one selections from an assortment of Psalters, other Scripture passages adapted for singing, hymns based on Bible topics or themes, and other selections that are consistent with Scripture as interpreted by the Westminster Standards. So, in the words of the Lord spoken in Psalm 98:4-6,

Barry Waugh

Notes—Trinity Hymnal, Revised¸ 1990, is available for purchase, as of today, from its publisher, Great Commission Publications, which is a ministry of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC). A copy was not available to me for this article, but Carl Trueman’s Luther on the Christian Life, Crossway, 2015, may be helpful regarding Luther and worship music; its table of contents can be located online via the usual vendors.

Sources—Luther’s Works, Liturgy and Hymns, vol. 35, edited by Ulrich S. Leupold and Helmut T. Lehman, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1965. Stephen J. Nichols, Martin Luther: A Guided Tour of his Life and Thought, Phillipsburg: P&R, 2002. James M. Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and his Career, Augsburg: Minneapolis, 1986. Herman J. Selderhuis, John Calvin: A Pilgrim’s Life, Downers Grove: IVP, 2009; also, edited by Selderhuis, The Calvin Handbook, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009, translated from the Dutch of 2008. Scott M. Manetsch, Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609, Oxford: OUP, 2013.