William Richmond Smith was born May 10, 1752 in Pequea, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to Rev. Robert Smith and his wife, Elizabeth Blair Smith. He was one of seven children, two of whom died in infancy, two became physicians, and three—Samuel Stanhope, John Blair, and William Richmond became ministers. However, William would not enjoy the same degree of academic and ecclesiastical prominence as his two brothers, but like his brothers, his college preparatory education was in the academy operated by his father. The gospel of Christ was presented to him from the pulpit by his father and at his mother’s knee.

William Richmond Smith was born May 10, 1752 in Pequea, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to Rev. Robert Smith and his wife, Elizabeth Blair Smith. He was one of seven children, two of whom died in infancy, two became physicians, and three—Samuel Stanhope, John Blair, and William Richmond became ministers. However, William would not enjoy the same degree of academic and ecclesiastical prominence as his two brothers, but like his brothers, his college preparatory education was in the academy operated by his father. The gospel of Christ was presented to him from the pulpit by his father and at his mother’s knee.

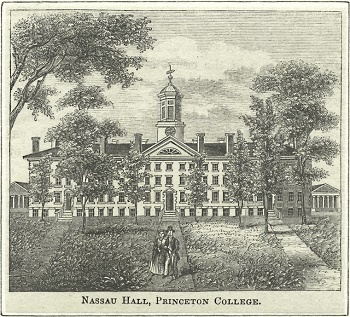

As did other members of the Smith household, William went to Princeton College. Five other members of his Princeton class had been taught by his father in the academy in Pequea. Even though he was four years older than his brother John Blair, the two began their studies together in the fall of 1773. No reason is given for why Will was over twenty when he started his college studies, but he may not have been as studious as his brothers due to his apparent preference for clowning around. William’s parents may have hoped that Will’s matriculation with his studious and steady younger brother would provide both a good bookish example and a watchful eye keeping tabs on Will’s activities.

One of Smith’s friends in Princeton was Philip Vickers Fithian, who graduated one year before Will in 1772 and then moved to Virginia to become a tutor. As William struggled through his studies during his final year, he sent Fithian a few letters that related campus and town news and expressed his fervent anticipation of graduation. One problem often encountered by collegians in the past was the poor-quality food served by the campus steward. For example, when James H. Thornwell was president of South Carolina College the students rioted over their less than palatable food. Smith mentioned in one letter that the Princeton students were so disgusted with the poor-quality butter served in the campus dining room that someone carved an image of Jonathan Baldwin, the steward, from a block of butter and hung it by its slippery neck in the dining room. It was February and the image survived melting due to the frigid conditions of eighteenth-century New Jersey life and the less than efficient sources of heat. Bold William took the effigy down, walked to Baldwin’s table, and handed it to him. Smith’s double-entendre comment to Fithian regarding the event was, “I believe [the butter effigy] does not sit very easy upon his stomach.” Baldwin, not too long after the effigy incident, was replaced.

At the time of Will Smith’s graduation in 1773, Princeton held its annual commencement at the end of September. Likely all graduates were happy when commencement arrived, but in William’s case graduation was the end of a necessary but painful process. William the jokester expressed his thoughts regarding the completion of his program to Fithian saying, “Fe—o—whiraw, whiraw, hi, fal, lal, fal, lal de lal dal a fine song—commencement is over whiraw, I say again whiraw, whiraw,” the meaning of which is unclear but may have been a common ditty sung by Will over a tankard of ale in a Princeton pub. Whatever the source of the ditty, the verse expresses the great relief felt by Will due to his liberation from the toils of study.

William’s graduating class of thirty-one may have been a difficult one for him to get along with due to its staid and studious membership. It included not only his very bright brother, John, but also William Graham—founder of what is currently Washington and Lee University; James F. Armstrong—moderator of the Presbyterian Church general assembly in 1804; Philadelphia physician Hugh Hodge—the father of theologian Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary; Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee—soldier, politician, and the father of Gen. Robert E. Lee; John Witherspoon, Jr.—the son of Princeton President John Witherspoon; and the frontier Pennsylvania Presbyterian known for his punctuality and diligence, Samuel Waugh. Several members of the classes on campus during William’s residency were important for the Revolution, such as Aaron Burr, and they went on to serve in both state and national governmental offices. Maybe Will’s pranks alleviated any intimidation he felt from such a gathering of future movers and shakers while elevating his position as the class comedian.

William’s graduating class of thirty-one may have been a difficult one for him to get along with due to its staid and studious membership. It included not only his very bright brother, John, but also William Graham—founder of what is currently Washington and Lee University; James F. Armstrong—moderator of the Presbyterian Church general assembly in 1804; Philadelphia physician Hugh Hodge—the father of theologian Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary; Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee—soldier, politician, and the father of Gen. Robert E. Lee; John Witherspoon, Jr.—the son of Princeton President John Witherspoon; and the frontier Pennsylvania Presbyterian known for his punctuality and diligence, Samuel Waugh. Several members of the classes on campus during William’s residency were important for the Revolution, such as Aaron Burr, and they went on to serve in both state and national governmental offices. Maybe Will’s pranks alleviated any intimidation he felt from such a gathering of future movers and shakers while elevating his position as the class comedian.

Following his graduation, the comparatively limited pool of information on William R. Smith dwindles to a mere puddle. It is likely that his father tutored him in divinity after college to prepare him for licensure by New Castle Presbytery in 1776 or 1777. Three years later he accepted a call from the Second Presbyterian Church in Wilmington, Delaware, where he was ordained and installed by Newcastle Presbytery. He succeeded a minister named Joseph Smith (no known relationship to the more famous Joseph Smith). As a churchman, he was the moderator of his presbytery in 1784 and attended meetings of the Synod of New York and Philadelphia several times through to 1788. He and his father were commissioners from New Castle Presbytery to the Second General Assembly of the PCUSA in 1790, but then the next year he attended the assembly as a visitor, not a commissioner. Will the pastor served in Wilmington from 1780 into 1795.

William Smith’s next call would not only involve a change in location and flock but also a new denomination. It is not known for certain why, but Pastor Smith left the Presbyterian Church to serve in the Reformed Dutch Church in its Neshanic and Harlingen congregations in New Jersey. For a bit of speculation, why did he change from Presbyterian to Reformed Dutch? His biographer in Princetonians, W. Frank Craven, has theorized that some ministers in the Presbyterian Church and other denominations were so disturbed by the infidelity of the age of Tom Paine—Common Sense, deism, the Enlightenment, rationalism, etc.—that they minimalized their denominational-constitutional distinctives in order to be unified against the rationalist infidels. It is not a bad theory, but William’s reason could have been more practical and not very theological—on February 5, 1795, William married a Dutch woman named Rachel Stidham who was eighteen years his junior.

The Neshanic Reformed Church had been established August 25, 1752 by eleven individuals dismissed for the purpose from a local congregation. Neshanic later separated itself from a group of local churches with which they had been sharing a minister in order to unite with the Harlingen Church. When Neshanic-Harlingen’s pastor, Johannes Martinus van Harlingen, died in 1795, William R. Smith succeeded him. One of the factors the congregations found particularly attractive about Smith was his ability to preach and teach the younger church members in English. The Dutch were concerned for their succeeding generations to have facility with the language of their recently formed new nation and its English constitution. He continued with Neshanic-Harlingen until his death on February 23, 1820. Rachel survived him until her passing on January 8, 1849. His grave inscription reads, “Sacred to the memory of Rev. William Smith for 25 years as one of the ministers of the United Congregations of Shannick [Neshanic] and Harlingen.” The stone Neshanic Church building in which Rev. Smith led worship was completed in 1762 and is still in use.

With regard to honors and publications, Pastor Smith is credited with having published for his presbytery a discourse titled An Address from the Presbytery of New-Castle to the Congregations under their care: Setting forth the declining State of Religion in their bounds; and exciting them to the Duties necessary for a Revival of decayed Piety amongst them, Wilmington, 1785. He was honored by serving for twenty years on the board of trustees of Rutgers College, which at the time was named Queens College. Two of the Smiths’ sons went on to graduate from Queens College.

The building in the accompanying photograph is the Queens College building which had its corner stone set April 27, 1809. The structure took some time to complete because it was not occupied until 1825, possibly due to logistical complications caused by the War of 1812 combined with financial difficulties. The design is very much like Alexander Hall on the Princeton Seminary campus which had its corner stone set in 1815. The Princeton building appears to be quite a bit larger than the similar structure on the Queens campus.

The building in the accompanying photograph is the Queens College building which had its corner stone set April 27, 1809. The structure took some time to complete because it was not occupied until 1825, possibly due to logistical complications caused by the War of 1812 combined with financial difficulties. The design is very much like Alexander Hall on the Princeton Seminary campus which had its corner stone set in 1815. The Princeton building appears to be quite a bit larger than the similar structure on the Queens campus.

There were eight children born to William Richmond and Rachel Stidham Smith that were baptized in the Neshanic Church: Anne Dubois, born September 14, 1795, baptized January 18, 1796; Elizabeth, born October 19, 1796, baptized October 29; Mary Colesberry, born January 3, 1798, baptized July 8; Robert Stidham, born February 19, 1800, baptized April 26; William Richmond, born July 21, 1802, baptized August 22; Jane McCroskrey, born May 15, 1804, baptized July 15; Margaret Van Arsdalen, born April 17, 1806, baptized June 14; and Samuel Stanhope, named for Will’s older brother, born August 8, 1808, baptized September 30. The name of “John Blair,” William’s other minister brother, was not given to one of the sons, so could it be John really did keep tabs on Will at Princeton?

Barry Waugh

Notes , The header showing a scenic setting for a stone church was used because neither an appropriate institution nor portrait could be found. The date of death given on Rachel Smith’s grave marker is said to be 1849 by the Find a Grave contributor, but the 4 looks like a 1 to me in the low resolution picture. The use of “Reformed Dutch Church” instead of “Dutch Reformed Church” is because in the eighteenth century it was the accepted name of the denomination. For more information about the Reformed Dutch Church, see John Henry Livingston, 1746-1825. Sources include: the Smith letters in Philip Vickers Fithian, Journals and Letters, 1767-1774, Student at Princeton College 1770-72, Tutor at Nomini Hall in Virginia 1773-74, edited by John Rogers Williams for the Princeton Historical Association, 1900. The Somerset County Historical Quarterly, 1914, provided the baptismal records of the Neshanic Reformed Church and the birth dates of the children. The information on Smith’s ministry in the Reformed Dutch Church was located in History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches, of its Prominent Men and Pioneers, by James P. Snell, Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881. Information regarding Queen’s College were found in Rutgers College, Founded as Queen’s College, 1766, c. 1883, which also provided the picture of the Queens building, and the biographical catalog titled, Trustees, Faculty, Alumni, and Students of Rutgers, Queens College, 1766-1916, 1916. Information about his Synod of New York and Philadelphia years was found in the Minutes of the Presbyterian Church in America, 1706-1788, which was edited by Guy S. Klett and published by the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, 1976.