Even though the United States did not enter the First World War until 1917, there were several Americans that defied President Wilson’s policy against U.S. involvement and left the country to help in the war effort. One of the many men and women that decided to cross the Atlantic and assist France in its fight against the Germans was Joseph Volney Wilson (no known relationship to President Wilson). Young Wilson was listed in the minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) among the chaplains that died in France. He did die in France, but Lt. Wilson, as it turned out, was not a chaplain even though he had been studying in the States for the ministry. He was instead a pilot who flew at first for the French Lafayette Escadrille and then for the United States.

Even though the United States did not enter the First World War until 1917, there were several Americans that defied President Wilson’s policy against U.S. involvement and left the country to help in the war effort. One of the many men and women that decided to cross the Atlantic and assist France in its fight against the Germans was Joseph Volney Wilson (no known relationship to President Wilson). Young Wilson was listed in the minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) among the chaplains that died in France. He did die in France, but Lt. Wilson, as it turned out, was not a chaplain even though he had been studying in the States for the ministry. He was instead a pilot who flew at first for the French Lafayette Escadrille and then for the United States.

Joseph Volney Wilson, who was known to family and friends as “Volney,” was born to Rev. Gill Irwin and Amanda (Robb) Wilson on September 16, 1895. Rev. G. I. Wilson was a member of the class of 1899 of Western Theological Seminary which was a Presbyterian seminary in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. Western would consolidate with Pittsburgh-Xenia Seminary in 1958 when the PCUSA merged with the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA). Volney’s father went on to serve his years of ministry in western Pennsylvania and West Virginia. At the time of Volney’s birth his father was busy studying to fulfill the educational requirements necessary for the ministry. Volney was the Wilsons’ second son; the first-born son, Gill Robb, was born almost to the day two years before Volney.

In his autobiography, I Walked with Giants, older brother Gill Robb Wilson has provided information about his beloved younger brother and the Wilson household. Rev. Wilson raised his two sons with an interest in the growing field of aviation. Volney and his brother were exposed to aviation through their father’s collection of articles and publications about balloons, gliders, and the many attempts to achieve powered flight. When news of the Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903 was published in the periodicals and scientific journals of the day, it thrilled eight-year-old Volney and ten-year-old Gill Robb as they contemplated soaring through the sky like birds. However, it may have thrilled them too much. Gill Robb told the story of how he and his brother attempted to build a functioning glider. They managed to complete a device that looked something like it might fly. Gill Robb commented that he tried to fly “from the woodshed roof” but “instead plowed up the yard with his face, and broke a shoulder blade” (32-33).

In his autobiography, I Walked with Giants, older brother Gill Robb Wilson has provided information about his beloved younger brother and the Wilson household. Rev. Wilson raised his two sons with an interest in the growing field of aviation. Volney and his brother were exposed to aviation through their father’s collection of articles and publications about balloons, gliders, and the many attempts to achieve powered flight. When news of the Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903 was published in the periodicals and scientific journals of the day, it thrilled eight-year-old Volney and ten-year-old Gill Robb as they contemplated soaring through the sky like birds. However, it may have thrilled them too much. Gill Robb told the story of how he and his brother attempted to build a functioning glider. They managed to complete a device that looked something like it might fly. Gill Robb commented that he tried to fly “from the woodshed roof” but “instead plowed up the yard with his face, and broke a shoulder blade” (32-33).

Volney, like his brother Gill, went to Kiskiminetas Preparatory School in Indiana County, Pennsylvania, to make ready for his studies in Washington and Jefferson College. Most likely, he planned to follow in the footsteps of his father and older brother by attending Western Theological Seminary for his ministerial education. Volney completed his studies at Kiskiminetas and had likely either completed or nearly completed his education at Washington and Jefferson by the time the war began.

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austro-Hungary and his wife Sofie were assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, it kicked off a series of events that mobilized empires to begin The Great War. Volney and his big brother were greatly interested in the aviation aspects of the conflict. Both young men wanted to go to France despite President Wilson’s policy of neutrality. As the war progressed, Volney read a book about some Americans who went to France and enlisted to drive ambulances for the French, which provided them with the way to get their toes in the door to enter flying school and fight in combat. Volney and Gill thought the tactic had merit, so they adopted it for their own. The problem obstructing their grand endeavor was a lack of the money needed to pay their fares to France. The aspiring pilots sold personal possessions and took jobs of all types to raise funds. Volney was the first to sufficiently fill his wallet for the pricey purchase of a ticket for France.

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austro-Hungary and his wife Sofie were assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, it kicked off a series of events that mobilized empires to begin The Great War. Volney and his big brother were greatly interested in the aviation aspects of the conflict. Both young men wanted to go to France despite President Wilson’s policy of neutrality. As the war progressed, Volney read a book about some Americans who went to France and enlisted to drive ambulances for the French, which provided them with the way to get their toes in the door to enter flying school and fight in combat. Volney and Gill thought the tactic had merit, so they adopted it for their own. The problem obstructing their grand endeavor was a lack of the money needed to pay their fares to France. The aspiring pilots sold personal possessions and took jobs of all types to raise funds. Volney was the first to sufficiently fill his wallet for the pricey purchase of a ticket for France.

Hopeful-aviator Volney arrived in France and began his contribution to the war effort serving with the Norton-Harges Ambulances in 1917. His hope to use ambulance driving to enter aviation was realized when he enlisted with the French Lafayette Escadrille, July  21, 1917, and then completed aviator training in November. He served with Escadrille Br. 117. When the United States entered the war Volney was transferred to an American squadron where he was immediately promoted from corporal to first lieutenant. The jump in rank was likely due to his many hours of flying experience with the French and the need for qualified officers to train and command American rookie pilots. Volney had been awarded the Croix de Guerre with star by the French for his “great and remarkable courage” on Feb. 5, 1918, when he “shot down an enemy plane during a bombing run over a distant target.” Volney was an instructor for the Americans from July 1 to September 30, 1918. He returned to the front and flew a few more weeks before he was killed in the line of duty on October 23, 1918. Any death in combat is both tragic and terrifying, but young Volney was killed when he fell out of his airplane and plummeted to the ground during a dog-fight maneuver. Unfortunately, if he could have survived just a few more weeks the war would have ended, but there were, sadly, many that died during those last days of The Great War. Gill Robb had made it to France a few months after his brother and was a pilot in a different area of conflict at the time of Volney’s death. Gill Robb noted that when his brother was killed he had been serving as the senior flight leader of his squadron of De Havilland DH-4 aircraft.

21, 1917, and then completed aviator training in November. He served with Escadrille Br. 117. When the United States entered the war Volney was transferred to an American squadron where he was immediately promoted from corporal to first lieutenant. The jump in rank was likely due to his many hours of flying experience with the French and the need for qualified officers to train and command American rookie pilots. Volney had been awarded the Croix de Guerre with star by the French for his “great and remarkable courage” on Feb. 5, 1918, when he “shot down an enemy plane during a bombing run over a distant target.” Volney was an instructor for the Americans from July 1 to September 30, 1918. He returned to the front and flew a few more weeks before he was killed in the line of duty on October 23, 1918. Any death in combat is both tragic and terrifying, but young Volney was killed when he fell out of his airplane and plummeted to the ground during a dog-fight maneuver. Unfortunately, if he could have survived just a few more weeks the war would have ended, but there were, sadly, many that died during those last days of The Great War. Gill Robb had made it to France a few months after his brother and was a pilot in a different area of conflict at the time of Volney’s death. Gill Robb noted that when his brother was killed he had been serving as the senior flight leader of his squadron of De Havilland DH-4 aircraft.

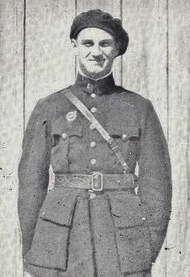

The smiling face of Volney seen in his portrait is similar to the happy faces of many promising young individuals that died in The First World War. Youthful optimism combined with the desire for adventure and excitement led many to defy President Wilson and find a way to contribute to the war effort before the United States declared war in April 1917. Volney had planned to become a missionary in Alaska and use his flying for ministry. His experience as a combat pilot would have provided the required skills for maneuvering the rugged and mountainous terrain of Alaska as he traversed its great distances and used its fields for landing and taking off.

Barry Waugh

Notes–The header image of the Dehaviland is from Wikimedia and it shows a Canadian aircraft, Wilson is not in the picture; the DH-4 was built through most of the war and it had several variations in details. The designation of J. V. Wilson as a chaplain was found in the 1919 edition of the PCUSA General Assembly minutes. Gill Robb Wilson notes that during Volney’s time in France his colleagues called him “Joe,” but I chose to continue calling him Volney. Gill Robb returned to Western Seminary after the war to continue his interrupted education. He went on to be the minister of Fourth Presbyterian Church, Trenton, New Jersey, until about 1930 or 1931 when he became the New Jersey State Director of Aviation, and he was a member of the commission that studied the cause of the Hindenburg disaster, May 6, 1937. Fourth Presbyterian Church in Trenton was the site of a trial in early 1935 when New Brunswick Presbytery brought charges against J. Gresham Machen for his support of the Independent Board of Foreign Missions. G. R. Wilson continued as a member of his presbytery even though it appears he was not an active minister. He was involved in many aspects of aviation during his lifetime including editing Flying Magazine. To read about a chaplain that died in France, see the biography of one in the Presbyterians of the Past article, Centennial U. S. Entry World War I, Chap. T. M. Bulla, 1881-1918, and for more about Presbyterians in the war read, Over There, Presbyterians in the First World War. Also, a series of articles is available on this site regarding the YMCA service of J. Gresham Machen.

Sources–Thank you to Wayne Sparkman of the P.C.A. Historical Center for his searching minutes for information for this article. The information about Volney’s service with the Lafayette Escadrille, was found in vol. 1, of The Lafayette Flying Corps, eds. J. N. Hall, C. B. Nordhoff and E. G. Hamilton, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1920. Volney is also mentioned in The Lafayette Escadrille, by H. M. Mason, Jr., New York: Random House, 1964, page 296. The information about those who flew for the Lafayette Escadrille is sometimes conflicting and terminology about squadrons and their relationship to the French military is not consistent.