One aspect of Presbyterian Church history is that many members of the denomination tended to be professionals such as accountants, doctors, academics, lawyers, and similar vocations. Obviously, there is nothing wrong with Christians working in these professions and they need to worship like anyone else, but Paul’s instruction regarding the variety and individual ministries of the body of Christ and James’s concern to rebuke favoritism to the wealthy combine to encourage churches to minister to all people. This is a difficult task because like tends to draw like, but churches should assess whether their Great Commission ministry is to all the world. Despite the disparity there were many Presbyterians that wore clothes without white collars whether they lived in the country or major cities. One Presbyterian of the past, Wesley Martin, started his working career as a laborer in the textile industry.

One aspect of Presbyterian Church history is that many members of the denomination tended to be professionals such as accountants, doctors, academics, lawyers, and similar vocations. Obviously, there is nothing wrong with Christians working in these professions and they need to worship like anyone else, but Paul’s instruction regarding the variety and individual ministries of the body of Christ and James’s concern to rebuke favoritism to the wealthy combine to encourage churches to minister to all people. This is a difficult task because like tends to draw like, but churches should assess whether their Great Commission ministry is to all the world. Despite the disparity there were many Presbyterians that wore clothes without white collars whether they lived in the country or major cities. One Presbyterian of the past, Wesley Martin, started his working career as a laborer in the textile industry.

Wesley Fletcher Martin was born near Dalton, Georgia, May 3, 1850. He enlisted in the Confederate Army during the last year of the war. Note that he would have been about fourteen years of age at the time he signed on. The regiment’s commander, Major General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, appointed Wesley a courier because of his diminutive stature and feather weight of only sixty pounds. His size made for a lighter load, greater speed, and a smaller target as he sat astride his galloping steed bearing military messages from commander to commander. Several years after the war, Wesley moved to Greenville, South Carolina, and shortly thereafter married Miss Mattie C. Land of Anderson on January 20, 1878.

Martin was an active citizen of Greenville not only in his employment but also in his church and public service work. Greenville’s textile industry was on the move as mills opened in the Upcountry in abundance. Some mills were owned by Presbyterians such as E. A. Smyth who was the son of a minister of Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, Thomas Smyth. The textile industry provided Wesley with twenty years of employment weighing cotton. Along with his paying work, he was an active and respected member of the Greenville Volunteer Fire Department. In 1884, Mr. Martin became captain of Lee Fire Company and twelve years later was elected assistant fire chief serving a tenure of two years. Wesley and Mattie were charter members of Second Presbyterian Church when it was organized on March 17, 1892. The congregation worshipped in the space above what is currently a restaurant at One Augusta Street in the Farmers’ Alliance Cotton Warehouse (built 1890). Some members of the Martins’ church were mill owners and supervisors, so Wesley may have been seated next to his boss for worship.

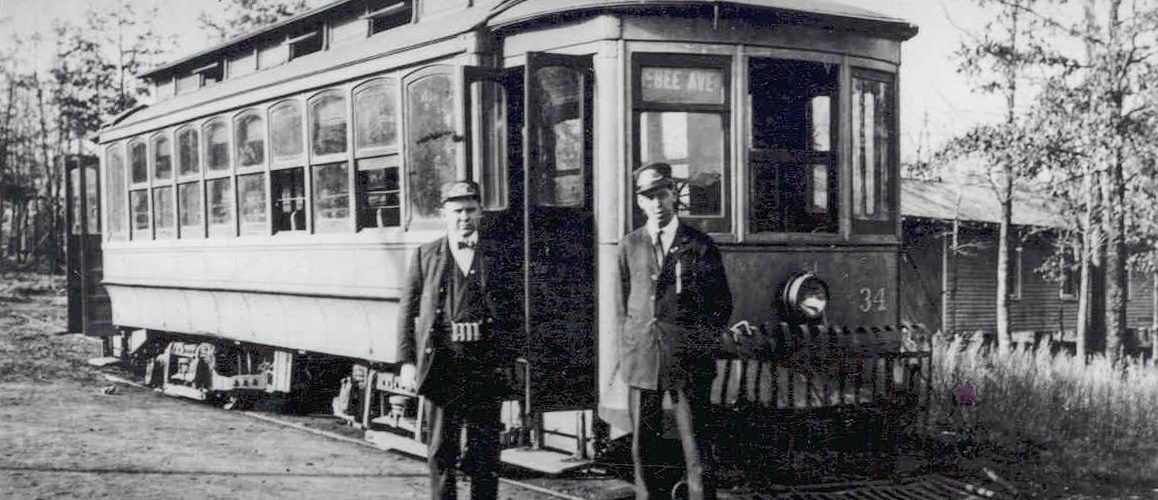

The increasing use of electric driven rail vehicles made its way to Greenville when the first trolley rolled through town in 1901. It left the car barn on Broad Street, then followed the track to Main where it stopped at the Mansion House Hotel to board dignitaries and then continued along the route ending its journey at the Poe Mill. All went well except for a delay caused by the removal of muck from the tracks. The “muck” likely was manure and other stuff which the trolley operator avoided to protect his prominent passengers from having their clothing soiled. Trolleys were seen not only as a means for transportation but also as environmentally friendly devices that would supplant equestrian traffic with its polluting oodles of odious output. When the trolley stopped at Poe Mill it signified that all Greenville routes led to textiles. Unfortunately, Poe Mill has joined the multitude of textile related industries in the South that have closed their doors over the years as manufacturing and its associated employment have been shipped abroad. Currently, portions of the Poe Mill site have been recycled for other uses including a skating park. The first roll down the rails in Greenville in 1901 would be followed by a multitude of others as the commercial district facilitated transportation for economic growth.

The trolley system became particularly important for Wesley Martin when he left the mill to work for Greenville’s street rail company. One occurrence of note during his trolley motorman years had significance for the famous baseball player, Shoeless Joe Jackson. Tim Hornbaker in Fall from Grace recounts that while driving his trolley Captain Martin delivered to Joe Jackson a custom-made bat just completed by a local craftsman. This was the famous bat which came to be named “Black Betsy.” Jackson began his organized baseball playing on the team from the mill which employed him. The bat was a significant part of Jackson’s image. Joe could play without shoes, but he could not play without Black Betsy.

In 1915, the Greenville Daily News published an article concerning the fine record of Captain Martin as a trolley motorman.

The Southern Public Utilities Company started at the first of the year a system of recognition of service on the part of its employees. The company awards one gold stripe for each year’s service up to five years, when a gold star is awarded. Capt. W. F. Martin was given his uniform with two stars and four stripes upon it [see portrait], which signifies that he has been in the employ of the company for fourteen years. Captain Martin ran the first car which moved over the lines of the Greenville Traction Company, nearly fifteen years ago. Ever since that time he has been a faithful and efficient employee of the company and though the management has changed, he was prized by his new employers just as if his long service of fourteen years had been under their management. Captain Martin had the unique distinction of having been a motorman for ten years and having avoided any accident during that time. For the past four years he has been an inspector.

Even though the days of yore are sometimes viewed through naive lenses replete with dancing in the daisies and Judy Garland singing Meet me in St. Louis, there were hazards and troubles as in any era. Transportation using horses had dangers, but mechanically propelled vehicles such as automobiles, trolleys, and trains added speed and mass to the hazard equation. Moses D. Hoge died after a number of painful days due to injuries received when his buggy was hit by a trolley and B. M. Palmer passed away after an accident involving a street car. For Wesley Martin to have achieved ten-accident-free years at the tiller of his trolley was quite an accomplishment. A street car could avoid accidents only by varying speed and using its brakes, neither method was reliably effective. A horse spooked by the trolley, a little child chasing a dog across the rails, or an inattentive teamster not holding his horses could all lead to mishaps or tragedies. Driving a trolley required patience, persistence, even preterition.

Wesley F. Martin died in the morning of October 7, 1915 in his residence on Garlington Street after suffering an illness that lasted for several months. At the time he was taken ill he was employed by the Southern Electric Utilities Company as an inspector of the local street railway system. His funeral service was conducted in the family residence with A. A. Bristow, J. R. Smith, Tandy Walker, Thomas W. Earle, H. Berry Ingram, and J. E. Gwinn serving as pallbearers. Mattie survived Captain Martin by over two decades. After many years as a wife, mother, church member, and homemaker she passed away on January 11, 1936 at the age of 81. The bodies of Wesley and Mattie await the resurrection in Springwood Cemetery. According to the Greenville Daily News obituary for Wesley, the Martins had four girls and one son—Mrs. E. M. Henderson of New York, Mrs. M. E. Garrison of Easley, Mrs. Homer Dillard and Mrs. J. H. Massey of Greenville, and Mr. H. Curtis Martin, of Binghamton, New York.

Wesley F. Martin died in the morning of October 7, 1915 in his residence on Garlington Street after suffering an illness that lasted for several months. At the time he was taken ill he was employed by the Southern Electric Utilities Company as an inspector of the local street railway system. His funeral service was conducted in the family residence with A. A. Bristow, J. R. Smith, Tandy Walker, Thomas W. Earle, H. Berry Ingram, and J. E. Gwinn serving as pallbearers. Mattie survived Captain Martin by over two decades. After many years as a wife, mother, church member, and homemaker she passed away on January 11, 1936 at the age of 81. The bodies of Wesley and Mattie await the resurrection in Springwood Cemetery. According to the Greenville Daily News obituary for Wesley, the Martins had four girls and one son—Mrs. E. M. Henderson of New York, Mrs. M. E. Garrison of Easley, Mrs. Homer Dillard and Mrs. J. H. Massey of Greenville, and Mr. H. Curtis Martin, of Binghamton, New York.

Barry Waugh

Notes–The author remembers reading a newspaper article contemporary to Martin’s earlier years as a trolley man that said someone else drove the first trolley in Greenville which differs with the 1915 account, but the exact paper and date is not remembered, sorry; Hornbaker’s book is Fall from Grace: The Truth and Tragedy of “Shoeless Joe Jackson,” New York: Sports Publishing, 2016, page 5; Firefighting in Greenville County, 1840-1990, by W. D. Browning, Jr., 1991, pages 16, 26; the header showing the McBee Avenue Trolley circa 1920 and the picture of the Augusta Street Trolley are from the Greenville County Library System Digital Collection. The portraits of the Martins are copies of originals used in Second Presbyterian Church Centennial, 1892-1992, published by the church; some of the information regarding the Martins is from Wesley’s obituary in the Greenville Daily News, Friday, Oct. 8, 1915; the date of the block quotation from an earlier issue of the News has not been ascertained other than the year was 1915; and neither an obituary or death notice for Mattie was located.