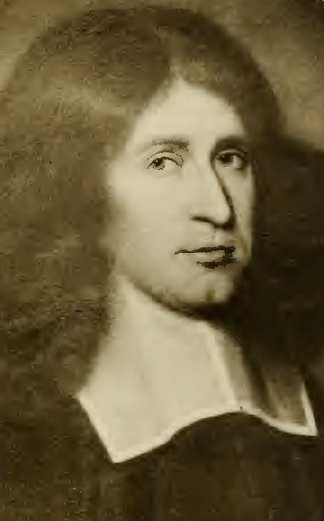

George Gillespie is one of eleven commissioners from Scotland in attendance at the Westminster Assembly and one of the youngest seated. At the time, he was the minister of Greyfriars Church in Edinburgh. No one despised his youth when he spoke to the issues particularly when he defended presbyterian polity against episcopacy. Of particular note in the ecclesiology discussions was his face off with academic, jurist, orientalist, and Member of Parliament, John Selden. Gillespie’s knowledge and oratorical skill resulted in encouragement from the commissioners to make his thoughts known. His works have been reprinted in editions including the two-volume set by Still Waters Revival Books in 1991. The transcription that follows includes some basic information about Gillespie’s brief life and material regarding his friendship with Samuel Rutherford, 1600-1661.

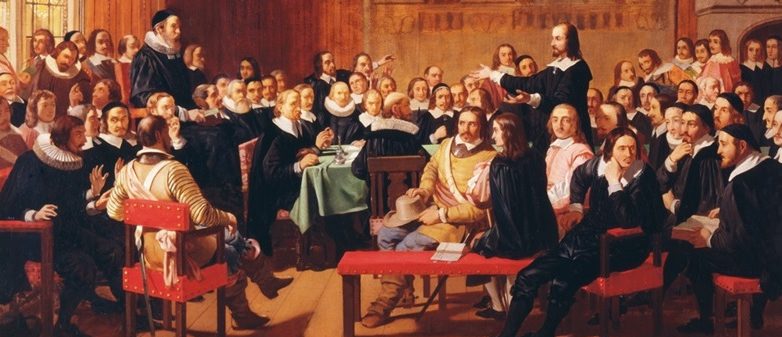

The text is taken from pages 151-160 of Samuel Rutherford and some of His Correspondents: Lectures Delivered in St. George’s Free Church, Edinburgh, by Alexander Whyte, D.D., Edinburgh and London, 1894. Each chapter of the book is Whyte’s lecture about Rutherford’s letter writing experiences with a contemporary. Whyte was a United Free Church of Scotland minister who lived 1836-1921, and he was the principal of New College, Edinburgh. He was moderator of the General Assembly in 1898. He also published Bunyan Characters: Lectures delivered in St. George’s Free Church Edinburgh, 1893. The quote heading Whyte’s lecture, “Our apprehensions are not canonical,” is from Rutherford’s letter to Gillespie, March 13, 1637. An invaluable resource for study of the Westminster Assembly is The Westminster Assembly Project website where the page “Members of the Westminster Assembly and Scottish Commissioners” provides a complete list of those invited while distinguishing the ones present from those who did not attend. The header image of the Westminster Assembly is kindly provided by Reformation Art. For biographies of Gillespie, Rutherford and other Westminster divines, see William S. Barker, Puritan Profiles: 54 Contemporaries of the Westminster Assembly, Christian Focus, 1996. Note Whyte says incorrectly that four Scots attended Westminster.

Barry Waugh

GEORGE GILLESPIE

“Our apprehensions are not canonical.”—Samuel Rutherford

George Gillespie was one of that remarkable band of statesman-like ministers that God gave to Scotland in the seventeenth century. Gillespie died while yet a young man, but before he died, as Rutherford wrote to him on his deathbed, he had done more work for his Master than many a hundred grey-headed and godly ministers. Gillespie and Rutherford became acquainted with one another when Rutherford was beginning his work at Anwoth. In the good providence of God, Gillespie was led to Kenmure Castle to be tutor in the family of Lord and Lady Kenmure, which allowed Rutherford and Gillespie to be continually together. Gillespie was still a probationer. He was ready for ordination and many congregations were eager to have him, but the patriotic and pure-minded youth could not submit to receive ordination at the hands of the bishops of the day, and this kept him out of a church of his own long after he was ready to begin his ministry. But the time was not lost to Gillespie, nor to the Church of Christ in Scotland—the time that brought Rutherford and Gillespie into the same neighborhood, also brought them into close and affectionate friendship. The scholarship of the two men would at once draw them together. They read the same deep books; they reasoned out the same constitutional, ecclesiastical, doctrinal, and experimental problems; till one day, rising from prayer in the woods of Kenmure Castle, the two men took one another by the hand and swore a covenant that all their days and amid all the trials they saw coming upon Scotland and her Church, they would remain fast friends, would often think of one another, would often name one another before God in prayer, and would regularly write to one another not only regarding church questions and the books they were reading, but more especially on the life of God in their own souls. Of the correspondence of those two remarkable men we have only three letters preserved to us, but they are enough to let us see the kind of letters that must have frequently passed between Kenmure Castle and Aberdeen, and between St. Andrews and Edinburgh during the next ten years.

Gillespie was born in the parish manse of Kirkaldy in 1613. He was ordained to the charge of the neighboring congregation of Wemyss in 1638, was translated thence to Edinburgh in 1642, and then became one of the four famous delegates who were sent up from the Church of Scotland to sit and represent her in the Westminster Assembly in 1643. Gillespie’s great ability was well known, his wide learning and his remarkable controversial powers had been already well proved, else such a young man would never have been sent on such a mission; but his appearance in the debates at Westminster astonished those who knew him best, and won for him a name second to none of the oldest and ablest statesmen and scholars who sat in that famous assembly. “That noble youth,” Baillie is continually exclaiming, after each new display of Gillespie’s learning and power of argument, “that singular ornament of our Church; he is one of the best wits of this isle,” and so on. And good John Livingston, in his wise and sober Memorable Characteristics, says that, being sent as a Commissioner from the Church of Scotland to the Assembly of Divines at Westminster, Gillespie “promoted much the work of reformation, and attained to a gift of clear, strong, pressing, and calm debating above any man of his time.”

Many stories were told in Scotland of the debating powers of young Gillespie exhibited on the floor of the Westminster Assembly. Selden was one of the greatest lawyers in England, and he had made a speech one day that both friend and foe felt was unanswerable. One after another of the Constitutional and Evangelical party tried to reply to Selden’s speech, but failed. “Rise, George,” said Rutherford to Gillespie, who was sitting with his pencil and notebook beside him. “Rise, George, defend the Church which Christ purchased with His own blood.” George rose, and when he had sat down, Selden is reported to have said to someone sitting beside him, “That young man has swept away the learning and labor of the years of my life.” Gillespie’s Scottish brethren took his notebook to preserve and send home at least the heads of his magnificent speech, but all they found in his little book were these three words: Da lucem, Domine; Give light, O Lord. Rutherford had foreseen all this from the days when Gillespie and he talked over Aquinas, Calvin, Hooker, William Ames, and Girolamo Zanchi as they took their evening walks together on the sands of the Solway Firth. It is told also that when the Committee of Assembly was engaged composing the Shorter Catechism and came to the question, what is God, like the able men they were, they all shrank from attempting an answer to such an unfathomable question. In their perplexity they asked Gillespie to offer prayer for help, he began his prayer saying, “O God, Thou art a Spirit, infinite, eternal, and unchangeable in Thy being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth.” As soon as he said Amen, his opening words were remembered, taken down, and they stand to this day the most scriptural and most complete answer to that unanswerable question that we have in any creed or catechism of the Christian Church.

As her best tribute to the talents and services of her youngest Commissioner, the Edinburgh Assembly of 1648 appointed Gillespie her Moderator, but his health was fast failing and he died in December of that year in the thirty-sixth year of his age. The inscription on his tombstone at Kirckcaldy ends with these sober and true words, “A man profound in genius, mild in disposition, acute in argument, flowing in eloquence, unconquered in mind. He drew to himself the love of the good, the envy of the bad, and the admiration of all.” Such was the life and work of George Gillespie, one of the most intimate and confidential correspondents of Samuel Rutherford—for it was to him that Rutherford wrote the words now before us, “Our apprehensions are not canonical.”

Every profession in life has its own language, its own peculiar vocabulary that none but its experts and those associated with the profession know. Go up to the Parliament House and you will hear the advocates and judges talking to one another in a speech that the learned layman no more than the ignorant can understand. Our doctors, again, have a shorthand symbolism that only themselves and the chemists understand. And so it is with every business and profession; each trade strikes out a language for itself. And so does divinity, especially experimental divinity, of which Rutherford’s letters are full. We not only need a glossary for the obsolete Scotch, but we need the most simple and everyday expressions of the things of the soul explained to us till once we begin to speak and to write those expressions ourselves. There are judges, advocates, doctors, and specialists of all kinds among us who will only be able to make a far-off guess at the meaning of my text just as I could only make a far-off guess at some of their trade texts. This technical term, “apprehension,” does not once occur in the Bible, and only once or twice in Shakespeare. “Our death is not in apprehension,” says that master of expression; and, again, he says that “we cannot outfly our apprehensions.” And Milton has it once in Samson, who says—

Thoughts, my tormentors, armed with deadly stings,

Mangle my apprehensive tenderest parts.

But, indeed, we all have the thing in us, though we may never have put its proper name upon it. We all know what a forecast of evil is—a secret fear that evil is coming upon us. It lays hold of our heart, or of our conscience, as the case may be, and will not let go its hold. And then the heart and the conscience run out continually and lay hold of the future evil and carry it home to our terrified bosoms. We apprehend the coming evil and feel it long before it comes. We die, like the coward, many times before our death.

Now, Rutherford just takes that well-known word, apprehensions, and applies it to his fears and his sinking heart about his past sins and about the unsettled wages of his sins. His conscience makes him a coward, till he thinks every bush an officer. But then he reasons and remonstrates with himself in his deep and friendly letter to Gillespie and says that these his doubts, terrors, and apprehensions are not canonical. He is writing to a divine and a scholar, as well as to an experienced Christian man, and he uses words that such scholars and such Christian men quite well understand and like to make use of. The canon that he here refers to is the Holy Scriptures; they are the rule of our faith, and they are also the rule of God’s faithfulness. What God has said to us in His word that we must believe and hold by; that, and not our deserts or our apprehensions, must rule and govern our faith and our trust, just as God’s word will be the rule and standard of His dealings with us. His word rules us in our faith and life, and it rules Him also in His dealings with our faith and with our life. God does not deal with us as we deserve; He does not deal with us as we, in our guilty apprehensions, fear He will. He deals with the apprehensive, penitent, believing sinner according to the grace and the truth of His word. His promises are canonical to Him, not our apprehensions.

Thomas Goodwin, that perfect prince of pulpit exegetes, lays down this canon, and continually himself acts upon it, that “the context of a scripture is half its interpretation…if a man would open a place of scripture, he should do it rationally; he should go and consider the words before and the words after.” Now, let us apply this rule to the interpretation of this text out of Rutherford, and look at the context, before and after, out of which it is taken.

Remembering his covenant with young Gillespie in the woods of Kenmure, Rutherford wrote of himself to his friend, and said, “At my first entry on my banishment here my apprehensions worked despairingly upon my cross.” By that he means, and Gillespie would quite well understand his meaning, that his banishment from his work threw him in upon his conscience, and that his conscience whispered to him that he had been banished from his work because of his sins. God is angry with you, his conscience said; He does not love you; He has not forgiven you. But his sanctified good sense, his deep knowledge of God’s word, and of God’s ways with His people, came to his rescue, and he went on to say to Gillespie that our apprehensions are not canonical. No, he says, our apprehensions tell lies of God and of His grace. So, they do in our case also. When any trouble falls upon us, for any reason—and there are many reasons other than His anger why God sends trouble upon us—conscience comes up immediately with her interpretation and explanation of our troubles. This is your wages now, conscience says. God has been slow to wrath, but His patience is exhausted now. As Rutherford says in another letter, our tearful eyes look asquint at Christ and He appears to be angry, when all the time He pities and loves us. Is there any man here tonight whose apprehensions are working upon his cross? Is there any man of God here who has lost hold of God in the thick darkness, and who fears that his cross has come to him because God is angry with him? Let him hear and imitate what Rutherford says when in the same distress: “I will lay inhibitions on my apprehensions,” he says, “I will not let my unbelieving thoughts slander Christ. Let them say to me ‘there is not hope,’ yet I will die saying, it is not so. I shall yet see the salvation of God. I will die if it must be so, under water, but I will die gripping at Christ. Let me go to hell, I will go to hell believing in and loving Christ.” Rutherford’s worst apprehensions, his best-grounded apprehensions, could not survive an assault of faith like that. Imitate him, and improve upon him, and say, that with a thousand times worse apprehensions than ever Rutherford could have, yet, like him, you will make your bed in hell, loving, and adoring, and justifying Jesus Christ. And, if you do that, hell will have none of you; all hell will cast you out, and all heaven will rise up and carry you in.

“Challenges” is another of Rutherford’s technical terms that he constantly uses with his expert correspondents. “I was under great challenges,” he says, in this same letter. In a letter written the same month of March to William Rigg, of Athernie, he says, “Old challenges revive, and cast all down.” Dr. Andrew Bonar, Rutherford’s expert editor, gives this gloss upon these passages: “Charges, self-upbraiding, self-accusations.” Challenges of conscience came to Rutherford like these: “Why are thou writing letters of counsel to other men? Counsel thyself first. Why art thou appealed to and trusted and loved by God’s best people in Scotland, when thou knowest that thou are a Cain in malice and a Judas in treachery, all but the outbreaks? Why art thou taking thy cross so easily, when thou knowest the unsettled controversy the Lord still has with thee?” “Vestibules are slippery,” wrote stern old Knockbrex, challenging his old minister for his too great joy, “Old challenges now and then revive and cast all down again.” That reminds me of a fine passage in that great book of Rutherford’s, Christ Dying, where he shows us how to take out a new charter for all our possessions, and for the salvation of our souls themselves when our salvation, or our possessions and our right to them, is challenged. It is better, he says, to hold your souls and your lands by prayer than by obedience, or conquest, or industry. Have you wisdom, honor, learning, land, eloquence, godliness, grace, a good name, wife, children, a house, peace, ease, pleasure? Challenge yourself how you got them and see that you hold them by an unchallengeable charter, even by prayer, and then by grace. And if you hold these things by any other charter, hasten to get a new conveyance made and a new title drawn out. And thus old, and angry, and threatening challenges will work out a charter that cannot be challenged.

And, then, when George Gillespie was lying on his deathbed in Edinburgh, with his pillow filled with stinging apprehension as is often the case with God’s best servants and ripest saints, hear how his old friend, Rutherford, now professor of divinity in St. Andrews, writes to him—

My reverend and dear brother, look to the east. Die well. Your life of faith is just finishing. Finish it well. Let your last act of faith be your best act. Stand not upon sanctification, but upon justification. Hand all your accounts over to free grace. And if you have any bands of apprehension in your death, recollect that your apprehensions are not canonical.

And the dying man answered—“There is nothing that I have done that can stand the touchstone of God’s justice. Christ is my all, and I am nothing.”