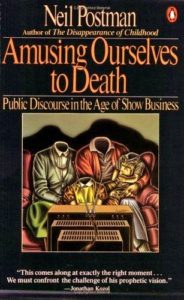

In 1985, Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, which considered the media, its influence on views, and the sound bite world of the time. Dr. Postman taught in the School of Education at New York University until his death in 2003. Following release of the book, it was quoted and referred to by ministers and teachers as they illustrated the problems television, movies, and entertainment in general created to dampen Evangelicalism’s interest in and grasp of theology. With thirty-four years gone by and other titles on similar subjects by Dr. Postman, not only is the media continuing its mortification of theology but now added to show business is the Internet’s social venues. The brevity of social media tends to limit the attention spans of individuals and inhibit their ability to contemplate the nuances of doctrine from which are drawn sound instruction for Christian living. If Dr. Postman were with us today to issue a revised edition of Amusing crafted for the twenty-first century, would it be re-titled Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the age of Social Media?

In 1985, Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, which considered the media, its influence on views, and the sound bite world of the time. Dr. Postman taught in the School of Education at New York University until his death in 2003. Following release of the book, it was quoted and referred to by ministers and teachers as they illustrated the problems television, movies, and entertainment in general created to dampen Evangelicalism’s interest in and grasp of theology. With thirty-four years gone by and other titles on similar subjects by Dr. Postman, not only is the media continuing its mortification of theology but now added to show business is the Internet’s social venues. The brevity of social media tends to limit the attention spans of individuals and inhibit their ability to contemplate the nuances of doctrine from which are drawn sound instruction for Christian living. If Dr. Postman were with us today to issue a revised edition of Amusing crafted for the twenty-first century, would it be re-titled Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the age of Social Media?

In the years after Postman’s book, David Wells touched on insights from Amusing in his copious critique of Evangelicalism’s disregard of doctrine titled, No Place for Truth, or Whatever Happened to Evangelical Theology? Wells’s book is worth a read in a twenty-first century context. His analysis of Evangelicalism in 1993 spotlighted its indifference or antipathy to theological issues. It was hailed by doctrine-sensitive church leaders for its insight, but despite the exposure provided by his analysis, Evangelicalism has increasingly embraced the new at the expense of the confessional and historical. The conveniences of texting and tweeting are not improving the situation. But how can one understand theology, which is in fact understanding Scripture and not an alien science, if literacy is not up to snuff? As Wells noted, page 197, English literacy levels in the United States in his day were in decline, so now over twenty-five years later—have they improved? Does not the brevity of texting, tweeting, and some other Internet venues work against literacy, thought, and cogent communication? School teachers will affirm that the teaching of punctuation and capitalization is more difficult with texting because it encourages abandoning proper forms. For some, writing becomes a continuous lower case collection of misspelled words. But maybe it is not all the writer’s fault because the tedious mechanism for composition on a smart phone is not conducive to good writing. Maybe a revised edition of No Place for Truth would include social media or the Internet in its title.

In the years after Postman’s book, David Wells touched on insights from Amusing in his copious critique of Evangelicalism’s disregard of doctrine titled, No Place for Truth, or Whatever Happened to Evangelical Theology? Wells’s book is worth a read in a twenty-first century context. His analysis of Evangelicalism in 1993 spotlighted its indifference or antipathy to theological issues. It was hailed by doctrine-sensitive church leaders for its insight, but despite the exposure provided by his analysis, Evangelicalism has increasingly embraced the new at the expense of the confessional and historical. The conveniences of texting and tweeting are not improving the situation. But how can one understand theology, which is in fact understanding Scripture and not an alien science, if literacy is not up to snuff? As Wells noted, page 197, English literacy levels in the United States in his day were in decline, so now over twenty-five years later—have they improved? Does not the brevity of texting, tweeting, and some other Internet venues work against literacy, thought, and cogent communication? School teachers will affirm that the teaching of punctuation and capitalization is more difficult with texting because it encourages abandoning proper forms. For some, writing becomes a continuous lower case collection of misspelled words. But maybe it is not all the writer’s fault because the tedious mechanism for composition on a smart phone is not conducive to good writing. Maybe a revised edition of No Place for Truth would include social media or the Internet in its title.

A reading of this post by some will result in the response, “Oh, just another old goat complaining about the new, youth, and change.” The new, youth, and change are sometimes good, but just because something is new, youthful, or a change does not necessarily mean it is good. Theology and the church are based on truth; truth does not change. The Bible is the Word of God and it is the Rock upon which the Christian stands after having been rescued from the miry clay (Psalm 40:2). Even though a lack of concern for historically defined educational curriculum and the negative influences of social media contribute considerably to what Evangelicalism has become, they are merely symptoms of a deeper problem—the confessional anchor line has been cut setting the movement adrift in the sea directed by whatever contemporary current comes along. The Bible is the source of confessions. It contains sixty-six books, hundreds of chapters, thousands of verses, and over three-quarters of a million words. Confessions are summaries of key doctrines in Scripture and subscription to one can keep Christians from following “every wind of doctrine” (Ephesians 4:14) and from failing to follow “sound doctrine” through heaping “to themselves teachers” who turn them “unto fables” (2 Timothy 4:3).

BARRY WAUGH

Notes–The picture of a bibliomaniac’s collection of books crammed into every nook and cranny is courtesy of Pixabay and was located using the search “bookshelf”.