Andrew was born to Nicholas and Mary (Wilson) Flinn in Maryland in 1773. Nicholas was an immigrant from Ireland and it is believed Mary was also. When Andrew was just over a year old the family moved to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. They attended the Sugaw (Sugar) Creek Presbyterian Church which had been established twenty years before their arrival. Nicholas died in 1786 and is buried in the church cemetery. Mary was left with six children and little money, so eleven-year-old Andrew provided some income running errands and doing odd jobs. His mother taught him the basics at home. She came to realize that her boy’s astonishing memory and voracious appetite for knowledge were unique gifts from the Lord, so she obtained the best education for Andrew she could with the household’s limited means.

Andrew was born to Nicholas and Mary (Wilson) Flinn in Maryland in 1773. Nicholas was an immigrant from Ireland and it is believed Mary was also. When Andrew was just over a year old the family moved to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. They attended the Sugaw (Sugar) Creek Presbyterian Church which had been established twenty years before their arrival. Nicholas died in 1786 and is buried in the church cemetery. Mary was left with six children and little money, so eleven-year-old Andrew provided some income running errands and doing odd jobs. His mother taught him the basics at home. She came to realize that her boy’s astonishing memory and voracious appetite for knowledge were unique gifts from the Lord, so she obtained the best education for Andrew she could with the household’s limited means.

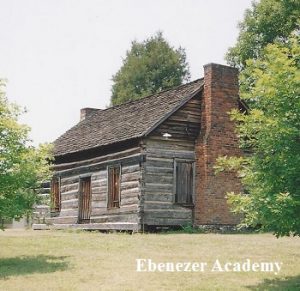

A graduate of the College of New Jersey in Princeton, James Hall, was the minister for Bethany Presbyterian Church near Statesville, North Carolina. He operated Ebenezer Academy in a log building on the church property. Hall was impressed with Andrew and added him to his rustic classroom full of students. Andrew proved to be a star pupil showing considerable abilities in Latin, Greek, and the sciences as he prepared for college. Flinn matriculated at the University of North Carolina as a member of its second class. He was admitted to the Dialectic Society which had adopted the motto “Love of Virtue and Science.” He proved proficient in his studies and became an instructor for the university. During Flinn’s final term in 1799 there was trouble on campus. Professor James S. Gillespie had become, according to some students, a heavy-handed taskmaster who was hearing impaired when it came to appeals from students to lighten the load. Some angry class men united in a general rebellion directing their ire not only at Gillespie but also other faculty, the student instructors, and the rules of the student code of conduct. They turned to violence and beat Professor Gillespie, pummeled and stoned Instructor Murphey, and then turned their violence toward Flinn who fortunately was saved from battery by some brave students who intervened. The unrest went on for several days leaving acting president Joseph Caldwell with his hands full as he tried to resolve the situation and keep both the faculty and trustees happy (sometimes a challenge for presidents of institutions of higher education). In the end peace was restored and Andrew graduated with the class of 1799. Three of the worst offending students were dismissed and Professor Gillespie did not return the next year. Campus unrest might be thought an innovation of the 1960s, but the early decades of the United States saw swords drawn, firearms wielded, horses ridden up staircases in campus buildings, and gunpowder exploded in rebellion at schools including South Carolina College (University of South Carolina) and the College of New Jersey (Princeton University). Graduate Flinn may have been relieved as he left campus to prepare for the ministry which involved spiritual dangers fought with the weapons of Ephesians 6.

A graduate of the College of New Jersey in Princeton, James Hall, was the minister for Bethany Presbyterian Church near Statesville, North Carolina. He operated Ebenezer Academy in a log building on the church property. Hall was impressed with Andrew and added him to his rustic classroom full of students. Andrew proved to be a star pupil showing considerable abilities in Latin, Greek, and the sciences as he prepared for college. Flinn matriculated at the University of North Carolina as a member of its second class. He was admitted to the Dialectic Society which had adopted the motto “Love of Virtue and Science.” He proved proficient in his studies and became an instructor for the university. During Flinn’s final term in 1799 there was trouble on campus. Professor James S. Gillespie had become, according to some students, a heavy-handed taskmaster who was hearing impaired when it came to appeals from students to lighten the load. Some angry class men united in a general rebellion directing their ire not only at Gillespie but also other faculty, the student instructors, and the rules of the student code of conduct. They turned to violence and beat Professor Gillespie, pummeled and stoned Instructor Murphey, and then turned their violence toward Flinn who fortunately was saved from battery by some brave students who intervened. The unrest went on for several days leaving acting president Joseph Caldwell with his hands full as he tried to resolve the situation and keep both the faculty and trustees happy (sometimes a challenge for presidents of institutions of higher education). In the end peace was restored and Andrew graduated with the class of 1799. Three of the worst offending students were dismissed and Professor Gillespie did not return the next year. Campus unrest might be thought an innovation of the 1960s, but the early decades of the United States saw swords drawn, firearms wielded, horses ridden up staircases in campus buildings, and gunpowder exploded in rebellion at schools including South Carolina College (University of South Carolina) and the College of New Jersey (Princeton University). Graduate Flinn may have been relieved as he left campus to prepare for the ministry which involved spiritual dangers fought with the weapons of Ephesians 6.

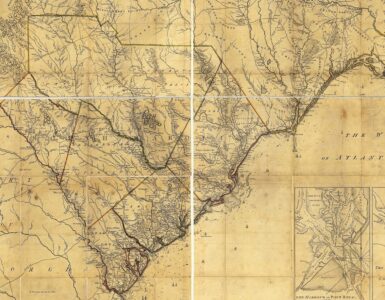

Andrew Flinn’s theological studies were directed by Orange Presbytery which licensed him to test his gifts for ministry, September 23, 1801. At the time, the presbytery included more than half the state of North Carolina. After nearly two years of continued study and pulpit supply in several area churches he was ordained June 2, 1803 and appointed to supply the church in Fayetteville which soon became his first pastoral call. Flinn came to appreciate the load his mentor James Hall carried as both a pastor and teacher because he too not only served a flock but also mastered an academy. It was too much for Flinn, so after a few years he began looking for another ministry. One of the fathers of the Presbyterian Church in the region, Colin McIver, said of Flinn’s Fayetteville years that his preaching had “a good deal of energy and always much pathos.” Flinn’s preaching ability would prove an important aspect of his ministry because he not only ministered the Word to his congregation but several others that were in need.

The next call came from southwest of Fayetteville in Camden, South Carolina, where Presbyterians had been gathering for services since before the Revolution. At the time, the third in the congregation’s series of buildings was under construction and it would be completed during Flinn’s tenure (the current Robert Mills designed church is the fourth building). A congregational meeting held July 6, 1805 issued a pastoral call to him that included a salary of eight-hundred dollars. It was a sizeable sum at a time when there were few ministers available to fill numerous empty pulpits in churches which often had little money to pay. The salary at Camden was to be raised through pew rentals, but if this method fell short, subscriptions would be required to make up the difference. Flinn was examined by First South Carolina Presbytery which scheduled his installation for January 1, 1806, and then the next month the congregation was organized into a particular church with five ruling elders elected. Flinn continued in Camden for a just few years until he moved to the Low Country in 1809 for a new ministry.

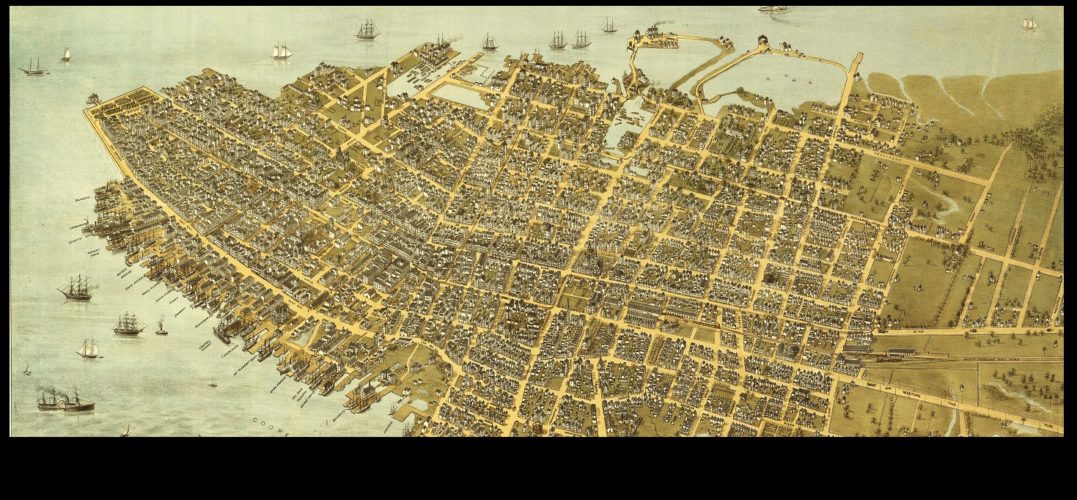

At the time of the American Revolution the Church of England had established two-dozen parishes along the South Carolina coast and it was the church of the British colony with other denominations considered dissenters. The Presbyterians, Huguenots, Methodist-Episcopals, and others needed permits from the Crown to gather for worship. There was only one Presbyterian church in Charleston before, during, and for several years after the Revolution, First Scots Presbyterian Church. It was full to overflowing with congregants and a second church was sorely needed. In 1804 a core group of Presbyterians gathered in the Huguenot Church (currently, the only extant Huguenot Church) where they were led in worship by Irish minister James Malcolmson until he died of yellow fever in September. It would not be till 1809 when the continued lack of seating at First Scots induced action again as fourteen men gathered and purposed to build a second church. Each man subscribed one-hundred dollars toward the salary for the man they hoped would pastor the new flock, Andrew Flinn. At the time he was serving the Williamsburg and Indiantown Churches a hundred miles north of Charleston, but he had filled the First Scots pulpit occasionally giving Charlestonians opportunities to assess his ministerial gifts. Those interested in formation of Second Presbyterian Church gathered in Trinity Methodist-Episcopal Church on April 24, 1809 to take the steps needed to achieve their goal. The group appointed a committee to pursue construction of a church building. Seventy-seven men signed the paper committing themselves to membership in Second Church. Dedication of the new building took place April 3, 1811 with Andrew Flinn delivering his sermon from 2 Chronicles 5:20 bearing the title, “God’s Perpetual Presence in and Constant Watchfulness Over His Church.” Pastor Flinn began what would be a popular, fruitful, and connectional ministry with other Presbyterians, but it was an unfortunately all too brief tenure. Reverend Andrew Flinn, D.D., passed away Thursday, February 24th, 1820. He was survived by his second wife, Eliza Grimball whom he married in 1808. Mary Augusta, the daughter of Flinn and his first wife, Martha H. Walker, also survived. Mary would be married to widower John Dickson, MD, in 1821. John and Mary’s son was named Andrew Flinn Dickson, who, like his name-sake grandfather, became a minister. George Reid delivered the memorial sermon for Dr. Flinn from Proverbs 10:7, “The memory of the just is blessed.” He commented about the deceased and his pastoral work.

He was ever active in works of beneficence. Public and charitable institutions of every kind engaged his heart; and he was always liberal in affording aid in the promotion of their benevolent designs. He was the friend of the poor; he often visited and sympathized with the sick; and in all the sorrows and afflictions of the distressed, he took a lively interest which was felt by them “who weep with those that weep.”

Pastor Flinn appears to be interred inside Second Church but it may be that his gravestone was placed there to protect it.

Andrew Flinn was not only an active pastor of the Second Church flock but also an involved citizen of Charleston and dedicated worker in the church courts. His interest in public education led to membership on the Board of Commissioners for Free Schools in Charleston, 1814-1820, during which tenure he was the chairman, 1815-1818. With regard to the extended church, in 1812, the PCUSA General Assembly gathered in First Church, Philadelphia, and Flinn convened the sessions for retiring Moderator Eliphalet Nott. It is an interesting occurrence because normally, if a moderator cannot convene the next assembly, then the most recent moderator present wielded the gavel. The text for Flinn’s sermon was 1 Corinthians 1:21. When time for election of the moderator came, Flinn was elected and became the second moderator from the southern states with James Hall having been the first. When Pastor Flinn returned to Philadelphia for the 1813 General Assembly he delivered his retiring moderator sermon from John 2:10. His participation that year included appointment to the Bills and Overtures Committee by Moderator Samuel Blatchford, and he was selected to deliver the annual missionary sermon one evening. One of the significant actions of the 1812 meeting involved sending a petition to Congress protesting the carrying and opening of mail on the Sabbath. The petition was delivered to U.S. Representative Langdon Cheves of South Carolina by Flinn, but he reported that “the prayer of the petition was not granted.” Also in 1813, he was appointed to the Assembly’s Standing Committee of Missions and continued on the committee till his death. His seat was filled by Moses Waddel. The 1819 Assembly elected him to the Board of Education for a one-year term. Of all the greater church service he did during his life it seems his work for Princeton Seminary was most important to him and the denomination. He was the agent of his presbytery for soliciting funds and gathering books for the seminary, 1810-1820, and he was a member of the Board of Directors, 1812-1817. A comment in the minutes for 1816 indicates Flinn had written a letter to the Assembly resigning from the seminary Board of Directors, but the Assembly “out of respect to Dr. Flinn, and in consideration of his liberality to the Seminary, did not agree to accept his resignation.” It is a cryptic comment and it begs Flinn’s reasons for wanting to resign. Was it declining health, a sense of inadequacy to the task, an inability to attend meetings, or possibly criticism from some individuals in the greater denomination regarding his views. That same year he subscribed to give 100.00 per year to Princeton. Andrew Flynn was a busy and effective pastor for his brief life. The University of North Carolina honored him with the Doctor of Divinity in 1809.

Andrew Flinn was not only an active pastor of the Second Church flock but also an involved citizen of Charleston and dedicated worker in the church courts. His interest in public education led to membership on the Board of Commissioners for Free Schools in Charleston, 1814-1820, during which tenure he was the chairman, 1815-1818. With regard to the extended church, in 1812, the PCUSA General Assembly gathered in First Church, Philadelphia, and Flinn convened the sessions for retiring Moderator Eliphalet Nott. It is an interesting occurrence because normally, if a moderator cannot convene the next assembly, then the most recent moderator present wielded the gavel. The text for Flinn’s sermon was 1 Corinthians 1:21. When time for election of the moderator came, Flinn was elected and became the second moderator from the southern states with James Hall having been the first. When Pastor Flinn returned to Philadelphia for the 1813 General Assembly he delivered his retiring moderator sermon from John 2:10. His participation that year included appointment to the Bills and Overtures Committee by Moderator Samuel Blatchford, and he was selected to deliver the annual missionary sermon one evening. One of the significant actions of the 1812 meeting involved sending a petition to Congress protesting the carrying and opening of mail on the Sabbath. The petition was delivered to U.S. Representative Langdon Cheves of South Carolina by Flinn, but he reported that “the prayer of the petition was not granted.” Also in 1813, he was appointed to the Assembly’s Standing Committee of Missions and continued on the committee till his death. His seat was filled by Moses Waddel. The 1819 Assembly elected him to the Board of Education for a one-year term. Of all the greater church service he did during his life it seems his work for Princeton Seminary was most important to him and the denomination. He was the agent of his presbytery for soliciting funds and gathering books for the seminary, 1810-1820, and he was a member of the Board of Directors, 1812-1817. A comment in the minutes for 1816 indicates Flinn had written a letter to the Assembly resigning from the seminary Board of Directors, but the Assembly “out of respect to Dr. Flinn, and in consideration of his liberality to the Seminary, did not agree to accept his resignation.” It is a cryptic comment and it begs Flinn’s reasons for wanting to resign. Was it declining health, a sense of inadequacy to the task, an inability to attend meetings, or possibly criticism from some individuals in the greater denomination regarding his views. That same year he subscribed to give 100.00 per year to Princeton. Andrew Flynn was a busy and effective pastor for his brief life. The University of North Carolina honored him with the Doctor of Divinity in 1809.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header image is cropped from a map held in the Library of Congress Digital Collection dated 1872. Information about his early life was informed by Neil R. McGeachy, A History of the Sugaw Creek Presbyterian Church Mecklenburg Presbytery Charlotte, North Carolina, 1954; my copy is a reprint celebrating the 250th anniversary in 2005. Regarding the University of North Carolina see, A Catalogue of the Members of the Dialectic Society, Instituted in the University of North Carolina, June the third, 1795, Raleigh, 1841. Regarding campus violence see volume one of History of the University of North Carolina, by Kemp P. Battle, 1907. See Daniel W. Howe, University of South Carolina: Volume I. South Carolina College in which the author says the walls built around the horseshoe were to keep rowdy students in and not outsiders out (more likely a case of killing two birds with one stone). Concerning the College of New Jersey, see Mark A. Noll’s Princeton and the Republic, 1768-1822, where he relates the student rebellion of 1797 as well as others in the college’s history, one of which included blowing up an outhouse (probably not hard to do with the methane atmosphere). A key source for all things in the Palmetto State that are Presbyterian is History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina, By George Howe, D.D., Professor in the Theological Seminary, Columbia, South Carolina. Prepared by Order of the Synod of South Carolina, vol. 2, Columbia: W. J. Duffie, 1883. McIver’s quote about Flinn’s ministry is in History of the First Presbyterian Church, Fayetteville, North Carolina, by Harriot Sutton Rankin, 1928. Robert H. Stone, A History of the Presbytery of Orange, Greensboro, 1970, is a very helpful book with maps, lists of licensures and ordinations, etc. First South Carolina Presbytery existed from 1800 to 1810 and was then divided to form Harmony Presbytery with the other portion of the division going to Concord Presbytery. There is a difference in the sources regarding when the organizational meeting for Harmony Presbytery occurred and its location, but it appears the record in G. R. Brackett’s An Historic Sketch of the Second Presbyterian Church, of Charleston, S.C. From its Beginning to the Present Time, 1898, is correct; Howe’s account does not make sense unless the Synod of the Carolinas had to postpone the gathering for a year. The dates of Flinn’s ministry in Camden do not sequence correctly and it seems he may have been a supply before being installed. Flinn’s dedication sermon for Second Church was published in Manual, for the Use of the Members of the Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, S.C. Prepared Under the Direction of the Church, edited by Thomas Smyth, 1838, but it was first published in Charleston and then reprinted in 1829 in Colin McIver’s Virginia and North Carolina Presbyterian Preacher; it also is available in volume 5 of The Works of Thomas Smyth, D.D., as edited by J. William Flinn (Andrew’s grand nephew). For the quote by Reid regarding Flinn see, A Sermon, Delivered in the Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, S.C., on the 17th of September, 1829, Commemorative of the Life and Labor of the Reverend Andrew Flinn, D.D., Late Pastor of Said Church, Charleston: J. Hoff, 1820. For a look at the strength of faith of 88 Presbyterian ministers on their death beds see, Alfred Nevin, How They Died; or, Last Words of American Presbyterian Ministers, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1883. John Augustus Dickson, the husband of Flinn’s daughter, taught briefly at the College of Charleston. For a good biography of him see, “Dickson, John Augustus,” by William F. Massengale, on NCPedia.