September 16, 1620, the crew of the Mayflower weighed anchor to leave Plymouth, England. The Pilgrims gathered on board were anticipating a new homeland, better economic opportunities, and freedom to follow God’s commands without interference. The ship held thirty-seven Pilgrims, sixty-five other colonists, thirty crew members, some small-breed livestock, and a few dogs. The ship’s decks were also filled with food, tools (including a blacksmith’s shop), clothing, water, beer, two cannons for defense, multiple firearms, and other items needed for the two-month journey and settlement in the new world.

September 16, 1620, the crew of the Mayflower weighed anchor to leave Plymouth, England. The Pilgrims gathered on board were anticipating a new homeland, better economic opportunities, and freedom to follow God’s commands without interference. The ship held thirty-seven Pilgrims, sixty-five other colonists, thirty crew members, some small-breed livestock, and a few dogs. The ship’s decks were also filled with food, tools (including a blacksmith’s shop), clothing, water, beer, two cannons for defense, multiple firearms, and other items needed for the two-month journey and settlement in the new world.

Everything was crammed onto this three-masted ship which measured ninety by twenty-five feet and weighed 180 tons. Three such ships could be set end to end between the goal lines of an American football field; it was nothing near a cruise ship, yet nevertheless a good vessel, and not unusual in an era acquainted with cramped living conditions.

Before continuing the narrative of the Plymouth Pilgrims, it is necessary to back-track and learn about who they were and what motivated them to leave for America.

The Pilgrims’ congregation began in the village of Scrooby on the River Ryton in North Nottinghamshire in the early 17th century. They gathered for worship in the manor house of one of their leaders, William Brewster, who had adopted Puritan teaching during his studies in Cambridge’s oldest college, Peterhouse.

Theologically, Pilgrims were Puritans. The definition of Puritan has been debated by historical theologians and sociological historians, with the latter often (and mistakenly) emphasizing their political motivations over their theological commitments. Puritans sought to reform (i.e. purify) the doctrine of the Church of England, pressing towards an adoption of Reformed theology and liturgy.

The Puritans have been unjustly caricatured as rough-and-ready factionalists, seeking out minor doctrinal errors in order to disrupt the Church of England. On the contrary, they sought thorough reform in the spirit of the Reformation’s sola Scriptura. Puritans had high regard for God’s universal Church as represented nationally by the Church of England, but they wanted changes that were more true to the teaching of the Bible.

As the years passed, however, growing hostility to change led many Puritans to leave the Church of England as Separatists (i.e. Non-conformists)—and such were the Pilgrims. Theirs was a road little traveled and fraught with peril. Separatists could face harassment, fines, even jail for worshipping freely. And their persecution extended beyond issues of worship. For example, they did not enjoy the same educational opportunities as those in the Church of England. Universities were overseen by the Church of England, and if one separated from its worship, then one also separated from the educational institutions it governed. Separatists were also social outcasts, as participation in England’s Church was a mark of national loyalty and status.

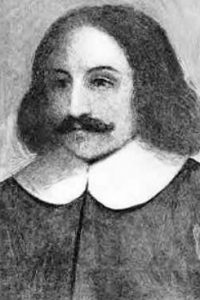

With several factors against them, the Pilgrims’ situation in England went from bad to worse, leading to their decision to leave for the bustling and prosperous trade center of Amsterdam. After meeting some impediments to their departure, they left in 1606 under the leadership of William Brewster, William Bradford, John Robinson, and the former Church of England minister, Richard Clifton.

In Amsterdam the Pilgrims found life among the city’s 100,000 residents a challenging cross-cultural experience. Language proved an obvious challenge but added to this was (despite the legal right to worship) interference with their gatherings by some individuals of the Dutch Reformed Church. Another difficulty was that back in Scrooby the Pilgrims experienced middling-sort respectability and prosperity, but in Amsterdam they were looked down upon and could not get similar jobs. The employment situation for them was so bad they moved to Leiden and worked in trades associated with the booming Dutch fabric industry. William Brewster, possibly the wealthiest of the Pilgrims, set up a printing business with Thomas Brewer and published tracts critical of the Church of England to smuggle into England for distribution.

After twelve years in Leiden, the Pilgrims had become increasingly concerned that their children were growing up Dutch instead of English, so they discussed options for relocation. They wanted a land with less government and more opportunities. Among the places considered were the Canary Islands, some of the Caribbean islands, and Guiana, which were all abandoned in favor of Virginia working with the support of the Virginia Company. In exchange for establishing the Pilgrims in a colony, the investors expected goods such as furs, fish, curiosities, lumber, and other saleable items to be shipped back to England for marketing.

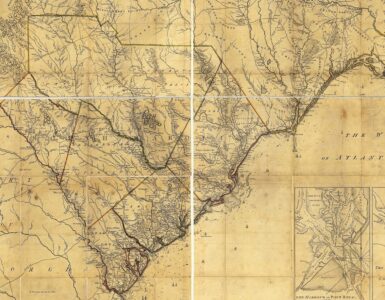

The stipulated destination for the Pilgrims was the northern edge of the Virginia Colony near the mouth of the Hudson River. It was a good plan, the Pilgrims remained concerned about a number of factors, such as the ship sinking, starvation at sea, attacks by pirates, poor sanitation, dread they might fall overboard, and—the bane of many novice ship passengers—sea sickness. Heading to America was a major step involving innumerable decisions and logistics, but the Separatists from Scrooby eventually took up the challenge.

Let’s return now to the port of Plymouth: The Mayflower weighed anchor and departed for the trans-Atlantic journey to America. During the sixty-six days of their crossing, passengers experienced the dangers, excitement, and sorrows of extended transit while living in close quarters. A child was born to Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins and given the seaworthy name Oceanus. The fear of going overboard was realized when John Howland was tossed into the sea as Mayflower rolled in the waves, but he survived by climbing a rope to get back on deck. William Bradford meanwhile noted that “many were afflicted with sea-sickness.”

The relationships between the Pilgrims and others on board did not always go well. One crewman, a “very profane young man,” cursed and condemned the sick Pilgrims every day, saying they should all be thrown overboard. About halfway through the trip the crewman died. Bradford expressed his opinion regarding the deceased crewman saying, “Thus his curses light on his own head; and it was an astonishment to all his fellows, for they noted it to be the just hand of God upon him.” The weather meanwhile was mixed; the Mayflower did encounter some horrible storms, one of which bowed and cracked one of the main beams. Yet considering the length of the journey, interpersonal conflicts, and some violent weather, the trip progressed well.

As land came into view, roaring waves and numerous shoals led the master of the Mayflower to anchor off Cape Cod on November 11, 1620, instead of sailing on to the Hudson River as their contract stipulated. The Pilgrims went ashore and fell on their knees and “blessed God of heaven, who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth.” Initially, the Cape Cod stop was intended to be temporary, but after consideration of their situation and the increasing dangers of sailing during winter, it was decided to remain at Cape Cod and search out the immediate region for a suitable settlement site.

Yet there was a problem: Since the settlers decided not to sail to the Hudson, their contract with the Virginia Company was broken. Some passengers became angry and made speeches, calling for people to join them and establish their own settlement and leave the Pilgrims and others to their own. Order and leadership were desperate needs. How would the mixture of Pilgrims, crew, and a variety of other colonists with varying religious commitments be governed?

The Pilgrims were experienced governing themselves. William Bradford commented that while they lived in Leiden, they never had to resort to the local magistrate because they policed their own people. Their church polity was congregational, which means each congregation shepherded itself with elders and all members were bound together by covenant. The covenant concept was important for those on board the Mayflower as they composed a document to direct their government. John Robinson was the pastor of the Pilgrims while they lived in Leiden and he had remained there with the members who chose not to leave. Well before the Pilgrims departed in July 1620, he sent a letter to John Carver. One paragraph is particularly important for the Pilgrims as they sought to establish civil government:

Whereas you are become a body politic, using amongst yourselves civil government, and are not furnished with any persons of special eminency above the rest, to be chosen into office of government, let your wisdom and godliness appear, not only in choosing such persons as do entirely love and will promote the common good, but also in yielding unto them all due honor and obedience in their lawful administration, not beholding in them the ordinariness of their persons, but God’s ordinance for your good; not being like the foolish multitude who more honor the gay coat than either the virtuous mind of the man, or glorious ordinance of the Lord. But you know better things, and that the image of the Lord’s power and authority which the magistrate beareth, is honorable, in how mean persons so ever. And this duty you both may the more willingly and ought the more conscionably to perform, because you are at least for the present to have only them for your ordinary governors, which yourselves shall make choice of for that work.

Robinson specifically noted that the responsibilities for the Pilgrims included not only governing themselves but also the other colonists as well as the crew until it returned the Mayflower to England. John Calvin’s emaciated remains had been buried in an unmarked grave for over sixty years, but his teaching from Scripture concerning separation of the ministry of the church from the ministry of the state was alive and well in that ship full of sea-weary passengers anchored at Cape Cod. With necessity for order at hand and the advice of John Robinson in mind, the Mayflower Compact was composed and signed:

In the Name of God, Amen.

We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.

Having undertaken, for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honor of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and one another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinance, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Domini 1620.

The Mayflower Compact echoes aspects of Robinson’s letter. Even though the Compact used “general good” instead of Robinson’s “common good,” the great sense of responsibility one to another is seen in their purpose to “Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Civil Body Politic.” The congregationalist Pilgrims covenanted as a church; the Pilgrims and their colonist colleagues covenanted as a state. If the settlement of Plymouth was to be successful, everyone had to work together; it was a matter of survival. Thirty-nine of the approximately seventy-four males on board ship signed the Mayflower Compact. John Carver was the first signatory, and he was the first governor of Plymouth until he died in early spring leaving the responsibility to William Bradford.

The Mayflower was moved from Cape Cod to the harbor accessing the Plymouth site, December 16, 1620. The site appeared to have been a village abandoned by the Wampanoags, which provided the Pilgrims with a clearing and head start for building a village. The first project on their list was building a common house for meetings and worship. Logs were manually dragged to the construction site because the settlers had no draught animals. By the end of January, the common house was completed with a thatched roof and ready for the first worship service which was led by Elder William Brewster.

Fear of the Indians was realized when some were seen at a distance watching progress of the village construction. The two cannons on board ship were transported ashore. In the spring the Pilgrims fears were alleviated when they made contact with the Wampanoag people and discussions led to a treaty with their leader, Massasoit. Settlement of the situation with the Wampanoags helped compensate for the horrors experienced during the winter. Disease and a scanty supply of food took their toll leaving only about fifty colonists alive. The Mayflower returned to England in April with its marketable cargo, but with its crew halved due to deaths from disease. The first months for Plymouth were difficult, but the Pilgrims and other colonists would continue to build their village, develop farms, worship in freedom, and provide goods for selling in England.

The Pilgrims should be remembered four-hundred years hence for their Christian dedication, virtue, persistence, work ethic, and commitment to covenantally govern themselves. The Covenant of Grace bound them redemptively to God and one another, while the political covenant of the Mayflower Compact bound them to their neighbors for the common good as administered by capable and pious leaders. Things did not always go well, but the Compact directed colonists to select civil leaders appropriate for the task of doing the best for all concerned. Working together was essential to survival and harmony in Plymouth.

It is terrible that during this year Plymouth Rock has been vandalized more than once with spray-painted graffiti and obscenities, but such actions are indicative of the fragmented society that is America today. In contrast to the Pilgrims, today we find more the spirit of Israel in the days of the Judges, when “every man did what was right in his own eyes” and cared little for either God or neighbor. Yet even as Israel repeatedly sinned, the Lord graciously sent Judges such as Gideon, Deborah, and Samson to deliver them. May God likewise deliver us from our selfishness, that we may better love Him and our neighbors—just as did the Pilgrims of old.

Barry Waugh

This article was first published on Ref 21, October 19 2020. The manuscript was improved by the editing done by Ben Ciavolella of the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals.

Notes—The header shows the Pilgrims in prayer upon arriving in Cape Cod. The portrait is William Bradford. It is not unusual for events of the past to be recounted in different sources with conflicting information, thus the specific date for the move to the Plymouth site from Cape Cod seems to be up in the air. Maybe this is why Plymouth Rock has engraved on it simply, 1620. It can be said for sure that the landing occurred in December and the sixteenth is believed to be the best day. The editions of William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation used are those edited by Samuel Eliot Morrison, 1993, and the two-volume edition published by the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1912. Due to the quadricentennial there are several websites remembering the Pilgrims’ Plymouth landing, including one for the United Kingdom.