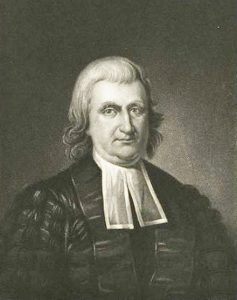

The following sermon was delivered the evening of Sunday May 10, 1789 by John Witherspoon to a sizeable crowd in New York’s Old First Presbyterian Church (founded 1716). John Rodgers was the pastor, and he would go on to edit an edition of Witherspoon’s works. Witherspoon had just passed his second decade in the presidency of the College of New Jersey where he not only molded the minds of a multitude of ministers, public servants, attorneys, and physicians while leading the school as a committed Presbyterian minister unashamed of his confessional Calvinist commitments and Scottish Common Sense Realism presuppositions. It is mindboggling to consider the magnitude of his influence upon the founding decades of the United States. His church work extended beyond pastoral guidance and preaching to his college students, to considerable activity in the judicatories, so much so that on May 21 Witherspoon would be honored as the convenor of the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America when it gathered in Philadelphia. He had been an instrumental part of the American Revolution as the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence, and as he spoke to the crowd in Old Church the United States Constitution was working its way through ratification for completion in 1790. Unfortunately, the reason the subject of educating children was selected is not known, but it may be he believed the foundation of everything he had worked for was in fact education in the home and church with families bound in the Covenant of Grace.

The following sermon was delivered the evening of Sunday May 10, 1789 by John Witherspoon to a sizeable crowd in New York’s Old First Presbyterian Church (founded 1716). John Rodgers was the pastor, and he would go on to edit an edition of Witherspoon’s works. Witherspoon had just passed his second decade in the presidency of the College of New Jersey where he not only molded the minds of a multitude of ministers, public servants, attorneys, and physicians while leading the school as a committed Presbyterian minister unashamed of his confessional Calvinist commitments and Scottish Common Sense Realism presuppositions. It is mindboggling to consider the magnitude of his influence upon the founding decades of the United States. His church work extended beyond pastoral guidance and preaching to his college students, to considerable activity in the judicatories, so much so that on May 21 Witherspoon would be honored as the convenor of the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America when it gathered in Philadelphia. He had been an instrumental part of the American Revolution as the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence, and as he spoke to the crowd in Old Church the United States Constitution was working its way through ratification for completion in 1790. Unfortunately, the reason the subject of educating children was selected is not known, but it may be he believed the foundation of everything he had worked for was in fact education in the home and church with families bound in the Covenant of Grace.

A few things to note are Witherspoon’s use of relative and real instead of non-communing and communing for the church membership of children; his use of the word condescension with respect to God’s gracious work through Christ in salvation and the Covenant; and his observations about the psychology of very young children and their ability to believe and exercise faith (Lutherans such as Norwegian Ole Hallesby in Infant Baptism and Adult Conversion, circa 1924, discuss this).

Witherspoon mentioned Richard Baxter (1615-1691) who is likely known to readers of this site, but likely unknown is “M. Fenelon” who was François de Salignac de la Mothe Fénelon (1651-1715). He was archbishop of Cambrai beginning in 1695 and came under influence of followers of the Quietist Madame Guyon. He wrote Maxims of the Saints. The text has been transcribed as published except for a few comments and clarifications included in [ ]. The enumeration in the original was not properly ordered and it has been changed for clarity (hopefully). The source is volume 2 of John Rodgers’s three-volume set of Witherspoon’s works, 1800. The header is New York circa 1837 (note the steamboat) which is the closest color image I could get to 1790, but it is a nice picture of the city as viewed from Brooklyn Heights. The portrait and header are from the NYPL digital collection.

Barry Waugh

On the Religious

EDUCATION of CHILDREN

A SERMON

Mark x. 13, 14, 15, 16.

And they brought young children unto him that he should touch them and his disciples rebuked those that brought them. But when Jesus saw it, he was much displeased, and said unto them, Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God. Verily I say unto you. Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, he shall not enter therein. And he took them up in his arms, put his hands upon them, and blessed them.

THERE are few things in which petitions of reflection, in general, and especially those who hear God, are more agreed, than the importance of the next generation; or, which is the true meaning of that expression, the importance of the instruction and government of youth.

This is a subject of great extent and may also be taken up in a great variety of lights. I am one of those who think that it may, as well as many others, be, with much advantage, considered doctrinally; and that a clear view of divine truth upon every subject, will have the most powerful and happy influence, not only in directing our sentiments, but in governing our practice.

There is much to be seen of the proper glory of the Redeemer in this passage of scripture. His usefulness—his attention to improve every seemingly accidental occurrence for the purpose of instruction, and his amiable condescension to all who humbly applied to Him, and tender feeling for their wants and weaknesses. It appears from this passage, that the inhabitants about Jordan, where he then was, not only brought their sick to be healed, as they did in most other places, but brought young children “that he should touch them.” In Luke they are called infants; and in the latter end of the passage now read, it is said, “he took them up in his arms, laid his hands on them, and blessed them”; so that it is probable they were all of them of very early age, and some of them, perhaps literally what we call infants who could not yet speak or walk. I see not the least foundation for what some commentators suppose, that they might labor under some disorder, from which the parents supposed he would cure them: If this had been the intention, the disciples would not, probably, have found any fault with it. The probability is, that the parents or relations of the children brought them, expecting that he would lay his hands on them—authoritatively bless them, and pray for them; from which they believed important benefits might be derived to them. The disciples, we are told, “rebuked those that brought them,” supposing, doubtless, that it was an impertinent and unnecessary interruption of their master, and that the children could receive no benefit at that early time of life; and who knows but, like the human wisdom of later times, they might think the attempt superstitious as well as unnecessary; however, our Lord was of a different opinion, and said—”Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not; for of such is the kingdom of God.”

Now the single subject of this discourse shall be to inquire, What is the import of this declaration? and, What we may understand our Savior as affirming, when he says, of young children or infants, “of such is the kingdom of God?” After this, I will give such advices [applications] as the truths that may be established shall suggest, and as they seem to me most proper to enforce.

Let us then confider what we may understand our Savior as affirming when he says, of young children or infants, “of such is the kingdom of God.”

(1.) And, in the first place, we may understand by it, that children may be taken within the bond of God’s covenant; become members of the visible church, and, in consequence, be relatively holy. I do not found the lawfulness of infant baptism on this passage alone, and mean to enter into no controversy on the subject this time; but, as it is clearly established in other passages, it may well be understood here. At any rate, so far as I have affirmed, it is undoubtedly certain, that they may be admitted within the bond of God’s covenant. We know, that under the Old Testament, they received the sign of circumcision, which in the New Testament, is said to be “a seal of the righteousness that is of faith” (Rom, iv. 11.). Many benefits may arise from this. As in the natural constitution of man many advantages and disadvantages are derived from parents upon the offspring, so in the moral constitution of divine grace many blessings, spiritual and temporal, may be inherited from pious parents. Children are the subjects of prayer; and, of consequence, within reach of the promise. The believer may justly hope for his seed dying in infancy, and in after life, many eventual providential mercies may be expected from that God who “Sheweth mercy to thousands of generations of them that love him.”

It was usual in the most ancient times, for aged or holy persons to bless children formally. I do not recollect in ancient history, a more beautiful, or more tender scene, than that we have recorded, Gen. xlviii. 15. of the patriarch Jacob blessing his grand-children, the sons of Joseph, when he was about to die—“And he blessed Joseph and said, God before whom my fathers, Abraham and Isaac, did walk, the God which fed me all my life long to this day, the angel which redeemed me from all evil, bless the lads; and let my name be named upon them, and the name of my fathers, Abraham and Isaac: And let them grow into a multitude in the midst of the earth.” We are told by an ancient writer of the Christian church, that Ignatius, afterwards bishop of Antioch, was one of those children thus brought to Christ for his blessing; and there is no reason, that I know of, to oppose the tradition. For supposing him to have been an infant, or even from 2 to 5 years of age, it would make him only between 70 and 80 at the time of his martyrdom, in the year 108 after the birth of Christ.

(2.) The declaration “of such is the kingdom of God,” may be understood to imply, that children may, even in infancy, be the subjects of regenerating grace, and thereby become really holy. This is plain from the nature of the thing; for if they can carry the corrupt impression of Adam’s nature in their infant state, there can be no doubt, but they may be renewed after the image of him that created them. Almighty power can easily have access to them, and can, in answer to prayers, as well as endeavors, form them for their Maker’s service. See what the prophet Isaiah says, xxviii. 9. “Whom shall he teach knowledge and whom shall he make to understand doctrine? Those that are weaned from the milk and drawn from the breasts.” Samuel was a child of prayer, and dedicated to God from his infant years, and it is said of him, I Sam. ii. 26. “And the child Samuel grew, and was in favor both with the Lord, and also with men.” It is an expression frequently to be found in pious writers, and among them that are far from denying the universal corruption of human nature, that some may be said to be sanctified from the womb—that is, that the time of their renovation may be beyond the reach both of understanding and memory; and this being certainly possible, may justly be considered as the object of desire and the subject of prayer. Few, perhaps, have failed to observe, that some children discover upon the first dawn of reason, an amiable and tractable disposition, and drink in spiritual instruction, with desire and delight; while others discover a frowardness and repugnance that is with much difficulty, if at all, and sometimes never overcome.

(3.) I think this declaration implies, that children are much more early capable of receiving benefit, even by outward means, than is generally supposed. No doubt the reason of the conduct of the disciples was, that they supposed the children could receive no benefit. In this, from our Lord’s answer, it is probable he thought them mistaken. I will not enlarge on some refined remarks of persons as distinguished for learning as piety; some of whom have supposed, that they are capable of receiving impressions of desire and aversion, and even of moral temper, particularly, of love or hatred, in the first year of their lives. I must, however, mention a remark of the justly celebrated M. Fenelon, archbishop of Cambray, because the fact on which it is founded is undeniable, and the deduction from it important. He says, that “before they are thought capable of receiving any instruction, or the least pains are taken with them, they learn a language. Many children at four years of age can speak their mother tongue, though not with the same accuracy or grammatical precision, yet with greater readiness and fullness than most scholars do a foreign language after the study of a whole life.” If I were to enlarge upon this I might say, they not only discover their intellectual powers by connecting the idea with the sign, but acquire many sentiments of good and evil, right and wrong, in that early period of their life. Such is the attention of children, that they often seem to know their parents tempers sooner and better than they know their own, and to avail themselves of that knowledge to obtain their desires.

To apply this to our present subject, or rather the occasion of it, allow me to observe, that the circumstances of solemn transactions are often deeply engraven upon very young minds. It is not impossible that some of those young children might recollect and be affected with the majesty and condescension of Jesus of Nazareth, and the impression be attended with happy fruits. At any rate, as no doubt the parents would often relate the transaction to their children, this would be a kind of secondary memory, and have the same effect upon their sentiments and conduct.

(4.) This declaration implies, that the earliest, in general, is the fittest and best time for instruction. This part of the subject has been treated at full length by many writers in every age, I therefore shall say the less upon it—Only observe, that the importance of early instruction is written upon the whole system of nature, and repeated in every page of the history of Providence. You may bend a young twig and make it receive almost any form; but that which has attained to maturity, and taken its ply, you will never bring into another shape than that which it naturally bears. In the same manner those habits which men contract in early life, and are strengthened by time, it is next to impossible to change. Far be it from me to lay any thing in opposition to the infinite power and absolute sovereignty of God; but let us also beware of considering these as opposed to the natural course of things, or the use and efficacy of means. We have many warnings upon this subject in scripture, where the recovery of an habitual and hardened sinner, is likened to a natural impossibility, Jer. xiii. 23.—“Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots? Then may ye also do good that are accustomed to do evil.” God will reserve to himself his own absolute sovereignty, but it is at every sinner’s own peril if he presumes upon it and abuses it.

(5.) This declaration of our Savior—“Of such is the kingdom of God”—may imply, that, in fact, the real disciples of Christ chiefly consist of those who are called in their earlier years. The visible church of Christ is a numerous and mixed society; but his mystical body, consisting of real believers, I think we are warranted from this passage of scripture and others, as well as the analogy of faith, and the reason and nature of things, to suppose, consists for the most part of those who are called in infancy and youth. This is an important truth, and deeply fraught with instruction to all, of every rank. There are some called after a course of opposition to God, but there are few in comparison; therefore, the apostle Paul styles himself—“One born out of due time.” Perhaps experience and a deliberate view of the state of the world, is sufficient to prove this assertion. The instances of conversion in advanced life, are very rare: and when it seems to happen, it is perhaps most commonly the resurrection of those seeds which were sown in infancy, but had been long stifled by the violence of youthful passions, or the pursuits of ambition and the hurry of an active life. I have known several instances of the instructions long neglected of deceased parents, at last rising up, asserting their authority, and producing the deepest penitence and real reformation. But my experience furnishes me with no example of one brought up in ignorance and security, after a long course of profaneness turning, at the close of life, to the service of the living God. The most common case is, that the deep sleep continues to the last, and, as the saying is, they die as they live; though in some instances, when the sins have been of the grossest kind, conscience awakens at their going off the stage, and they seem, as it were, to begin the torments of hell with the terror of despair.

You will find in some practical writers an opinion, or sentiment, that seems not ill founded to the following purpose, “Some are called at the eleventh hour that none may despair,” and there are few that now may presume. Others make a distinction, not without ground, as it seems founded upon the wisdom and equity of the divine government; That when the gospel comes to a people that had long sitten in darkness, there may be numerous converts of all ages; but when the gospel has been long preached in plenty and purity, and ordinances regularly administered, few but those who are called in early life are ever called at all. A very judicious and pious writer, Mr. Richard Baxter, is of opinion, that in a regular state of the church, and a tolerable measure of faithfulness and purity in its officers; family instruction and government are the usual means of conversion, public ordinances of edification. This seems agreeable to the language of scripture; for we are told God hath set in the church “apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors and teachers,” (not for converting sinners, but) “for perfecting of the saints for the work of the ministry, and the edifying of the body of Christ.” It seems to add further weight to this, that most of those who are recorded in scripture as eminent for piety, were called in early life; and we know not but it may have been the case with others, though not particularly mentioned: Those I have in view, are Abraham, Moses, Samuel, David, Solomon, Josiah, Daniel and the three Children [Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego], in the Old Testament, and in the New, John Baptist and John the beloved disciple; of whom I may just observe, that no other reason has ever been given for the Savior’s distinguishing him by particular affection, but that he was the youngest of the twelve.

(6.) In the last place, this declaration implies that the comparative innocence of children is a lesson to us, and an emblem of the temper and carriage of Christ’s real disciples. This instruction we are not left to infer for ourselves. Our Lord has made the remark in the passage where the text is, “Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child shall not enter therein.” This is directly levelled against the pride of self-sufficiency, and every rough and boisterous passion. It is remarkable that the very same image is made use of in several passages of scripture. Thus, Mat. xviii. 1, 2, 3, 4. “At the same time came the disciples unto Jesus, saying, ‘Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?’ And Jesus called a little child unto him, and set him in the midst of them, and said, ‘verily I say unto you, except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven. Whosoever, therefore shall humble himself as this little child, the same is greatest in the kingdom of heaven’.” So also, the apostle Paul, i Cor. xiv. 20. “Brethren, be not children in understanding: howbeit, in malice be ye children, but in understanding be men:”—And further, I Peter ii. 1, 2. “Wherefore laying aside all malice, and all guile, and hypocrisies, and envies, and all evil speakings—as new-born babes, desire the sincere milk of the word, that ye may grow thereby.” The graces of the spiritual life recommended to us by this beautiful image, are humility, gentleness, teachableness, sincerity, and calmness to be reconciled: all which are remarkable in young persons and are frequently dull or vitiated by growing years.

I come now to make a practical improvement [application] of this subject, which shall be confined to pointing out the duties suggested by the foregoing truths, as they are severally incumbent on, 1. parents; 2. children; 3. every hearer of the gospel.

(1.) Let us consider the duties incumbent on parents. Is it so that of children or infants the Redeemer said, of such is the kingdom of God? Then parents should be thankful. Thankfulness is a happy frame of spirit in itself, and powerfully reconciles the mind to difficult[ies], and animates it to important duties. Be thankful then for the honor that is done you, for the trust that is reposed in you, and for the encouraging promise of God to assist and accept of you in the discharge of it. “Children are the gift of God, and the fruit of the womb is his reward.” I cannot easily figure to myself any greater earthly blessings than to have children to be the objects of your care and diligence while you live, and to inherit your name and substance, when you yourselves must, in the course of nature, go off the stage. And is it a little honor to be entrusted with the care of these rational creatures of God, born for immortality, and whose present peace and future welfare depend so much on your conduct? Are you not called to prepare members for the church of Christ?—“for of such is his kingdom;” and however important the ministry of the gospel is (which I should be the last to detract from) you may know, that it is out of a minister’s power to speak to the understanding of those who are not prepared by previous instruction. But above all, how thankful should you be for the encouragement given you to bring your children to the Savior, and the promise of his blessing. “He took them up in his arms, laid his hands on them and blessed them.” Fathers! Mothers! What ground of praise to the condescending Savior!

(2.) Be early and diligent in instruction. This is the great and substantial evidence you are called to give of your thankfulness for the mercy. You have heard that children are much more early capable of receiving benefit by outward means than is commonly supposed: Let not, therefore, the devil and the world be too far before-hand with you, in possessing their fancy, engaging their affections, and misleading their judgment. Is it a fable, or do I speak truth when I say, many children learn to swear before they learn to pray? It is indeed affecting [discouraging], to a serious mind, to hear children lisping out ill-pronounced oaths, or scurrilous and scolding abuse, or even impurities which they do not understand; so that the first sentiments they form, and the first words they utter, are those of impiety, malice, or obscenity. Nay, I have seen children in their mother’s arms actually taught to scold, by uttering angry sounds, before they could speak one word with distinctness. It is wholly impossible for me here to introduce a system of directions as to the method of early instruction; this must be learned elsewhere and at another time; but I mean to impress your minds with a sense of the importance and necessity of the duty, and I will add the efficacy of it. Remember the connection between the duty and the promise—“Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old, he will not depart from it.” I knew a pious and judicious minister, who affirmed, that we did not give credit to that part of God’s word if we did not believe the certainty of the promise, as well as the obligation of the duty; he was of opinion, that every parent, when he seemed to fail, should conclude that he himself had been undutiful, and not that God had been unfaithful.

(3.) Be circumspect and edifying in your example. All the arguments that press the former exhortation, apply with the same, perhaps I may say, with double force to this. Example is itself the most powerful and successful instruction; and example is necessary to give meaning and influence to all other instruction. This is one of the oldest maxims upon the subject of education;—The Roman satirist says, Ni’l dictu visuve fœdum hæc limina tangat intra quæ puer est—”Let nothing base be seen or heard within these walls in which a child is.” And if children naturally form their sentiments, habits and manners, by imitation of others in general, how much more powerful must be the example of parents, who are every hour in their sight, whom nature teaches them, and whom duty obliges them to love, and when it comes recommended by the continual intercourse [interaction], and the endearing services that flow from that intimate relation.

(4.) Lastly, Parents are taught here perseverance and importunity in prayer. This, indeed, is an important thing upon every subject of our requests to God. Our Savior spoke a parable on purpose to teach men, that they should pray and not faint, Luke xviii. 1. And if we are called to believe, that “if we ask any thing agreeable to his will he heareth us,” what [is] more agreeable to his will than frequent and importunate prayer for the temporal and spiritual happiness of children?—What a support this to the faith of prayer. You ought, at the same time, to remember that, as the prophet Jeremiah says, “it is good for a man to hope and quietly to wait for the salvation of God.” The answer of prayer may come at a much greater distance than we are apt to look for it. There is a remarkable anecdote handed down to us, respecting the famous St. Augustine. He was the son of an eminently pious woman, whose name was Monica, yet he was in his youth very loose and disorderly. One of his fellow citizens, it is said, seeing him pass along the street, reflected upon him with great severity, as a disgrace to society; but another made answer, that he was not without hopes of him after all, for he thought it next to impossible that the son of so many prayers should perish.—And we know, that in fact, he became in due time one of the most eminent champions for evangelical truth. There is not the least doubt that many prayers, and especially of this kind, may have their answer and accomplishment after the believer that offered them has been many years sleeping in the dust.

The truths above illustrated, suggest important advices to children, that is, to such young persons as are able to understand and apply them.

(1.) Preserve a tenderness of heart, and be thankful that you are not yet hardened by habitual guilt, nor sentenced to perpetual barrenness by the judgment of a righteous God. Esteem, embrace, improve the precious but flying season [limited time you have]. Hearken to the instructions of parents; the admonitions of pastors; the lessons of providence; and the dictates of God’s holy spirit speaking by the conscience. Think of the amiableness of early piety in the sight of men; and its acceptableness in the sight of God—“I love them that love me,” says he by his prophet; “and they that seek me early shall find me.”

(2.) Be not satisfied with, or trust in outward privileges. If you are the children of pious parents, who have lived near to God; if you have been favored with early instruction, unless these advantages are improved, they will not plead for, but against you at the great day. This is the dictate both of scripture and reason, “to whomsoever much is given, of them much will be required.” There is a common saying, that is neither agreeable to truth nor experience, and yet sometimes obtains belief in a blinded world, that the children of good people are as bad as any: as if early education, which is of so much influence in learning every thing else, should have no effect in religion. On the contrary, where do we expect to find pious youth, but in pious families, or sober and industrious youth, but in sober and industrious families? I should call that man prudent in the conduct of life, who in the choice of a servant, an apprentice, or a partner in business, would pay almost as much attention to the blood and parentage, as to the person with whom he was to be immediately connected. But if we take notice of what probably gave occasion to the mistake, viz., that the wicked children of pious parents are the worst of any, it is a truth of the utmost moment, and easily accounted for. They burst asunder the strongest ties, they are under the unhappy necessity of mastering conscience by high handed wickedness, and commonly come to speedy and deserved ruin: “He that being often reproved, hardeneth his neck, shall suddenly be destroyed, and that without remedy.”

(3.) Do not satisfy yourselves with a name to live while you are dead. Though some young persons religiously educated, by falling into dissolute society, become open profligates, there are others who retain the form without the life of religion: Therefore, if nature hath given you amiable dispositions; if these have been cultivated by a pious and prudent education; if you feel the restraint of natural conscience; if you are desirous of public praise, or afraid of public shame, do not neglect any of these preservatives from sin; but yet endeavor to obtain, and see that you be governed by a principle superior to them all, the hope of final acceptance with God through Christ. Ask of him to give you a new heart, and a new spirit, to “create you anew in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained, that we should walk in them.”

In the last place, this subject suggests some important instructions to the hearers of the gospel in general.

(1.) Lose no time in providing for your great and best interest. Every argument that tends to shew the importance of early piety, may be applied, with equal or greater force, to shew the danger of delay in more advanced years. What is wise or amiable in youth, is necessary to those who are nearer their journey’s end. But considering myself as speaking to professing Christians, what I would earnestly advise you, is, to apply the principles above laid down, to particular purposes, as well as to your general conduct. If conscience or providence has pointed out to you any thing that you may do to advantage, either for yourselves or others, lose no time in setting about it, because you do not know how little time may be yours: So says the wise man, Ecc. ix. 10. “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might, for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave whither thou goest.”

(2.) Do not forget the improvement of this subject, which our Savior himself has pointed out; imitate the temper of children; learn to be humble and teachable, gentle and easy to be intreated. Both watch and pray against all violent attachments, rude and boisterous passions, and deep-rooted resentment. Observe how the little lambs lay down their resentment and forget their quarrels. Under this particular, it is proper to recommend a decency of deportment, and a contempt of all vanity and affectation, as well as simplicity and sincerity of speech, and a contempt of all artifice [trickery] and refinement. The apostle has given an excellent description of this, 2 Cor. i. 12. “For our rejoicing is this, the testimony of our conscience, that in simplicity and godly sincerity, not with fleshly wisdom, but by the grace of God, we have had our conversation in the world.”

(3.) Set a good example before others in general, but especially young persons. The old rule, Maxima debetur pueris reverentia [great respect is owed your children], ought to be pondered as well as recollected, it is of much importance what our visible conduct is, at all times and in all places, because we continually contribute to form each others tempers and habits; but greater caution is necessary in presence of young persons, both because they are most prone to imitation, and because they have the least judgment to make proper distinctions, or to refuse the evil, and choose the good. Some instances might be given, in which things might be said or done, before persons of full understanding, without injury, that could not be done without injury, or at least without danger, before persons in early life.

(4.) In the last place, be not wanting in your endeavors and prayers for the public interest of religion, and the prosperity of the Redeemer’s kingdom. Support, by your conduct and conversation, the public credit of religion.—What is more powerful over the minds of men and the manners of the age, than public opinion. It is more powerful than the most sanguinary laws. And what is public opinion? It is formed by the sentiments that are most frequently heard, and most approved in conversation. Had we a just sense of the importance of visible religion, what a powerful principle would it be of prudent, watchful, guarded conduct in every state and circumstance of life. Whatever reason there may be to complain of the frequency of hypocrisy, or seeking the applause of men, I am afraid there is no less reason to complain of the want of attention to that precept of the apostle, “Look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others;” or of our Lord himself, Matt. v. 16. “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.” I apprehend that these seemingly opposite faults, are not always separated, but often found in the same persons; that is to say, there may be a strong desire after, and endeavor to obtain public applause by a few splendid and popular actions, and yet but little attention to that prudent and exemplary conduct, which promotes public usefulness. Consider what you have heard, and the Lord give you understanding to improve and apply it, for Christ’s fake. Amen.