In the book review that follows, B. B. Warfield summarized the development of Christmas practices over the centuries and their prominence in his day. Even though his concluding comments are forceful, Warfield was not against Christmas as a seasonal celebration but instead thought it was an unnecessary addition to Scripture’s ecclesiastical calendar which cycles every seven days on the first day of the week. I have seen a Christmas card expressing seasonal sentiments of greeting and good will sent by him to his Princeton Seminary colleague J. Gresham Machen. The illustration on the cover is a snow-covered village. He must have accepted Christmas as a seasonal celebration, possibly as a national holiday of good will or a time to remember friends and family. The closing lines of the review show that marketing and gift giving were as common in Warfield’s day as they are now. He compares Christmas to the Roman holiday Saturnalia which is important because it ocurred in December and merged into the flow of practices that developed into Christmas as the ancient church centuries passed to the medieval.

In the book review that follows, B. B. Warfield summarized the development of Christmas practices over the centuries and their prominence in his day. Even though his concluding comments are forceful, Warfield was not against Christmas as a seasonal celebration but instead thought it was an unnecessary addition to Scripture’s ecclesiastical calendar which cycles every seven days on the first day of the week. I have seen a Christmas card expressing seasonal sentiments of greeting and good will sent by him to his Princeton Seminary colleague J. Gresham Machen. The illustration on the cover is a snow-covered village. He must have accepted Christmas as a seasonal celebration, possibly as a national holiday of good will or a time to remember friends and family. The closing lines of the review show that marketing and gift giving were as common in Warfield’s day as they are now. He compares Christmas to the Roman holiday Saturnalia which is important because it ocurred in December and merged into the flow of practices that developed into Christmas as the ancient church centuries passed to the medieval.

The source is The Princeton Theological Review, 1:3 (October 1903), 489-90. The book’s author, Georg Rietschel (1842-1914), was a professor of theology at Leipzig University and he wrote books on liturgy and the history of organ use in worship. B. B. Warfield studied at Leipzig so possibly they were acquainted; maybe Rietschel gave him the book. The book is written in German but the review is all in English. Warfield often made comments about the quality and aesthetics of books under review, and he does so with the present title. The Germans had developed technology that produced magnificient color prints and their postcards of the era were exceptionally vivid and beautiful as seen in the “Merry Christmas” card in the header. The portrait of Warfield as a boy is used courtesy of Wayne Sparkman from the collection of the PCA Historical Center.

I found the review interesting and thought provoking, but I think Christmas can be remembered conservatively and carefully as do my family and church. However, it is increasingly difficult to think of Christmas as remembrance of Jesus’ birth amidst the gifts and other aspects. The day involves fusing the sacred and secular and such efforts immediately or eventually simply do not work out well because Scripture comes in conflict with the world. I think the world has turned Christians from he who was “veiled in flesh, the Godhead see” to a cute baby that is nothing more than that. If we are to continue Christmas, the emphasis should be the supernatural work of God in the incarnation, God and man in two distinct natures and one person. I suggest you read the Creed of Chalcedon of AD 451 to see a historic confession descriptive of the miracle of the incarnation. You may not understand all the terminology but what you do understand is sufficient to induce awe. Chalcedon is available in Philip Schaff’s second volume of The Creeds of Christendom. [post revised 12-17-20]

Barry Waugh

Weihnachten in Kirche, Kunst und Volksleben, Von Prof. Georg Rietschel. Mit 4 Kunst beilagen und 152 Abbildungen. [Christmas in Church, Art and Popular Life. With 4 art Inserts and 152 Illustrations.]. Large 8vo, pp. 160. Bielefeld und Leipzig: Verlag von Velhagen und Klasing, 1902.

This comprehensive treatise on “Christmas,” beautifully illustrated with a profusion of half-tone and colored plates, is the fifth volume of a Sammlung illustrierter Monographies, herausgegeben in Vergindung mit Anderen von Hanns von Zobelitz [A Collection of Illustrated Monographs, edited by Hanns von Zobelitz in Association with Others]. It is from the very competent pen of Prof. Rietschel of Leipzig and gives a precis of the whole subject, drawn from the best authorities. After a short introduction it treats in turn of the Christmas Festival of the Church, Christmas and Pictorial Art, the Christmas Grotto, Christmas Songs, Christmas Plays, Various Christmas Customs, Christmas Presents and Christmas Markets, and the Christmas Tree. A useful bibliography and an index close the volume. The illustrations are numerous, well chosen and beautifully reproduced; they provide in themselves a pretty full history of Christmas ideas and usages as well as presenting a very rich series of reproductions of masterpieces of Christian art.

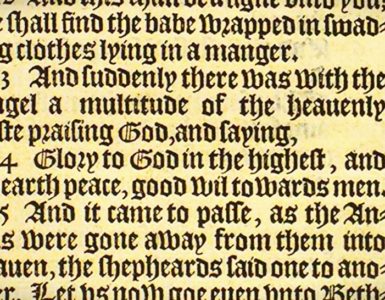

Prof. Rietschel tells us that no other Christian festival has so intimately wedded itself with the family life and the life of the people as Christmas. Nevertheless, for more than three hundred years the Church got along entirely without it. The primitive Church did not even possess a distinctively Christian Easter or Whitsunday. By the middle of the second century we find, however, Easter celebrated and soon afterwards Whitsunday; and by the end of the third century, or the beginning of the fourth, a third festival begins to appear in the East by the side of these. But this third festival was not Christmas but Epiphany; and it was celebrated on the sixth of January, along with which there gradually came to be made remembrance of the birth of Christ also. The idea that Christ was born on the 25th of December seems to appear first early in the third century as the result of a calculation from the 25th of March, the New Year’s day of that time, which had come to be looked upon as the anniversary of the Annunciation. But there is no trace of the celebration of this day until the middle of the fourth century. Prof. Rietschel thinks indeed that we can fix confidently on 354 (or possibly 353) as the exact year of its first celebration. This occurred at Rome; and thence the new festival spread—reaching Constantinople in 379, Cappadocia in 382, Antioch in 388, Egypt in 432; but Palestine not until the seventh century, while the great Armenian Church has resisted the innovation up to our own day.

If the celebration of the twenty-fifth of December as the birthday of the Lord dates thus only from the later Patristic age, the modes of its celebration most common among us are of yet more recent origin. The custom of giving presents upon Christmas Day is of mediaeval invention; the Christmas-tree a modern extension. We first hear of Christmas-presents late in the fourteenth century: and the usage made its way only slowly and against much opposition. It was even made the subject of legal enactments; and as late as 1661 and indeed as 1735 the Saxon “Policey-Ordnung” sought to regulate and provide against the abuses of this custom. The Christmas tree seems to have come in through a confusion of the festival of Christmas with the observance of “the day of Adam and Eve,” which fell on December 24th, and a feature of which was the erection of a “Paradise,” in which were planted the two trees of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and of Life. We appear to hear of our distinctive “Christmas-tree” first at Strassburg, at the opening of the seventeenth century. The “burning Christmas-tree,” that is the Christmas-tree adorned with candles, we meet with first about 1737. It was not until the nineteenth century that it began to spread very widely even in Germany. Neither in the North German States of Holstein, Mecklenburg, Pommerania and the Provinces of Prussia, nor in the Rhine-land in the West, nor in Bavaria in the South, was it in use until towards the middle of the nineteenth century. Outside of Germany it has appeared only as a German importation. Oddly enough the first Christmas-tree was set up in France and England in the same year, 1840, by the Mecklenburg Princess Helen, Duchess of Orleans, in the former, and by the Saxe-Coburg Prince Albert in the latter. “Thus the Christmas-tree,” smilingly remarks Prof. Rietschel, “has held its conquering way over the earth.”

It goes without saying that we have adverted only to a few of the numerous interesting facts brought out in this wide survey of Christmas usages. We have, indeed, confined ourselves to such as furnish a compressed account of the origins of the customs now most common in American families. The book is crammed full of other lines of investigation of equal inherent interest. Even such as we have briefly reported may supply us, however, with some food for thought. There is a certain passionate intensity in the way in which Christmas is now celebrated among us. But after all, what can be said for the customs to which we have committed ourselves. There is no reason to believe that our Lord wished His birthday to be celebrated by His followers. There is no reason to believe that the day on which we are celebrating it is His birthday. There is no reason to believe that the way we currently celebrate it would meet His approval. Are we not in danger of making what we fondly tell ourselves is a celebration of the Advent of our Lord, on the one side something much more like the Saturnalia of old Rome than is becoming in a sober Christian life; and, on the other something much more like a shopkeeper’s carnival than can comport with the dignity of even a sober secular life?

Princeton. Benjamin B. Warfield.