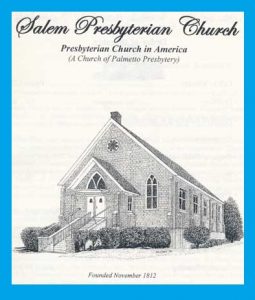

Salem Church in Blair, South Carolina, is one of the oldest congregations in the Presbyterian Church in America (P.C.A.). Harmony Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (P.C.U.S.A.) organized the church in 1812 and provided supply ministers because the congregation did not have sufficient funds to pay a full-time pastor. The records show that during the earliest years the church was most often supplied by Samuel Yongue. Just a few years before accepting the call to Salem and two other churches Yongue had been supplementing his ministerial income working in civil government. He was a court clerk and ordinary (similar to justice of the peace). At the time, he was a member of First Presbytery of South Carolina and the government job was preventing him from attending presbytery meetings. His government work as a minister came before the Synod of the Carolinas by means of an overture adopted by First Presbytery in October 1807. The overture sought the wisdom of synod “respecting the propriety of ministers of the Gospel accepting and holding civil offices which divert their attention from their ministerial duty and bring reproach upon the sacred ministry.” The Synod responded saying “those Presbyteries where such instances are to be found, [are] to … induce such ministers to lay aside such offices and devote themselves wholly to their ministerial duties” (Howe, 2:85). Further, the Synod instructed Yongue to appear before his presbytery regarding the question of continuing to work in the government. The presbytery discussed the situation with him and then sent an overture to the 1808 General Assembly asking if it is “inconsistent with the discipline of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America that ministers of the Gospel hold any civil office under our civil Government?” (2:86). When the case was decided, the Assembly referred the Presbytery “to the decision of the Assembly of 1806, on the same question” (Minutes, 399).

Salem Church in Blair, South Carolina, is one of the oldest congregations in the Presbyterian Church in America (P.C.A.). Harmony Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (P.C.U.S.A.) organized the church in 1812 and provided supply ministers because the congregation did not have sufficient funds to pay a full-time pastor. The records show that during the earliest years the church was most often supplied by Samuel Yongue. Just a few years before accepting the call to Salem and two other churches Yongue had been supplementing his ministerial income working in civil government. He was a court clerk and ordinary (similar to justice of the peace). At the time, he was a member of First Presbytery of South Carolina and the government job was preventing him from attending presbytery meetings. His government work as a minister came before the Synod of the Carolinas by means of an overture adopted by First Presbytery in October 1807. The overture sought the wisdom of synod “respecting the propriety of ministers of the Gospel accepting and holding civil offices which divert their attention from their ministerial duty and bring reproach upon the sacred ministry.” The Synod responded saying “those Presbyteries where such instances are to be found, [are] to … induce such ministers to lay aside such offices and devote themselves wholly to their ministerial duties” (Howe, 2:85). Further, the Synod instructed Yongue to appear before his presbytery regarding the question of continuing to work in the government. The presbytery discussed the situation with him and then sent an overture to the 1808 General Assembly asking if it is “inconsistent with the discipline of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America that ministers of the Gospel hold any civil office under our civil Government?” (2:86). When the case was decided, the Assembly referred the Presbytery “to the decision of the Assembly of 1806, on the same question” (Minutes, 399).

The case in 1806 involved Boyd Mercer of the Presbytery of Ohio, who, due to health problems, could not accomplish “the regular discharge of his public duties as a minister of religion,” so to earn a living he worked as an associate judge (Minutes, 364). One may wonder why Mercer had the stamina to sit on the bench and could not fulfill his ministerial work, but it could have been because early nineteenth century Ohio was at the edge of the frontier, the terrain could be difficult, and there were the hazards of winter combining to impede an invalid minister routinely visiting members and supplying pulpits. A nice warm fire while seated in court was better for the respiratory system and health in general. Despite the similarity of the Mercer case to that of Yongue, the General Assembly found the work acceptable while the Synod of the Carolinas had not. But the Assembly did caution ministers in its decision to beware of “a covetous, ambitious spirit,” that they “not aspire after places of emolument or civil distinction,” and that they as much as possible “avoid temporal avocations.” This was good advice for ministers, but it expanded the resolution of the case from an issue of church and state to one including any secondary work. If Mercer was a part time farrier, cooper, or wheelwright his secondary work may not have become an issue for the Presbytery of Ohio.

Returning to the subject of Salem Church, it united with Zion Church in Winnsboro to call Anthony W. Ross to be their pastor and he served from 1816 to 1822. Following Ross’s resignation and move to a church in Pendleton, Salem called William Brearly. Generally, ministers in South Carolina came from the Georgia and Carolinas area but Brearly was born in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, graduated both the College of New Jersey and Princeton Seminary, and then moved to South Carolina to be ordained and installed pastor of Salem Church in 1826. When he left Salem for his next call the communicant membership totaled thirty-three. By sometime in 1830, Robert Means, was the pastor. He had graduated South Carolina College, studied law, and while in practice was called to the ministry. Epidemics such as cholera, yellow fever, and typhoid were common in the day and Means became a victim of one in 1826 while he was pastor of First Church, Columbia. Whichever disease afflicted him it weakened him such that he could no longer pastor the Columbia congregation. The disease had also blinded one of his eyes. He died January 17, 1836 due to complications from a stroke.

Returning to the subject of Salem Church, it united with Zion Church in Winnsboro to call Anthony W. Ross to be their pastor and he served from 1816 to 1822. Following Ross’s resignation and move to a church in Pendleton, Salem called William Brearly. Generally, ministers in South Carolina came from the Georgia and Carolinas area but Brearly was born in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, graduated both the College of New Jersey and Princeton Seminary, and then moved to South Carolina to be ordained and installed pastor of Salem Church in 1826. When he left Salem for his next call the communicant membership totaled thirty-three. By sometime in 1830, Robert Means, was the pastor. He had graduated South Carolina College, studied law, and while in practice was called to the ministry. Epidemics such as cholera, yellow fever, and typhoid were common in the day and Means became a victim of one in 1826 while he was pastor of First Church, Columbia. Whichever disease afflicted him it weakened him such that he could no longer pastor the Columbia congregation. The disease had also blinded one of his eyes. He died January 17, 1836 due to complications from a stroke.

After Robert Means a succession of ministers served from one to five years. If you have read about other rural churches on this site, you know they often had difficulty finding ministers. Much of the worship leadership in rural locations was led by occasional or short-term supply ministers, or in some cases two or more churches would share a minister, as had Salem, and in some cases ruling elders would preach and lead services. After a year of ministry by Richard S. Gladney, R. C. Ketchum supplied the Salem Church flock for a time before being installed its minister and then serving five years ending in 1844. In conjunction with the Lebanon Church, Salem was served by Edwin Cater for two years ending in 1847, and by the time he left the church it had grown to a membership of 92. From 1850 to 1873 the church was served by ministers T. A. Hoyt (1851), Edward P. Palmer (1852-1857), Theodore E. Smith (1858-1862), and then by David Alonzo Todd, D. C. Boggs, Francis P. Mullally, and William Bell Corbett, M. D. (1869-1872). The church’s longest tenured minister thus far in its history was William W. Mills who began his combined call to Salem, Horeb, and Lebanon congregations in 1873 and continued for eleven years. During the year 1892, the congregation rejoiced in its dedication of a new building but was also saddened by the death of its pastor since 1885, Rev. H. B. S. Gariss. Taking the succession of ministers up to the end of the First World War were W. W. Sadler (1898), R. F. Kirkpatrick (1900-1902), J. R. Millard, (1903-1911), and Fleming D. Vaughan (1913-1918). Vaughan was given a leave of absence to be a military chaplain at Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, during the war, but he was unable to return to Salem because he died of pneumonia November 28, 1918 just a few weeks after the war ended. Possibly, the pneumonia was a result of the influenza pandemic. During Rev. Vaughan’s years at Salem Church the congregation grew to 205 members.

The current brick building is located on spacious grounds in the Fairfield County countryside. Salem is an appropriate name for the church because the setting is peaceful and verdant. As one pulls into the driveway and looks up to the brick sanctuary, the lovely magnolia tree may be seen to the right of the building (as of 2013). Though the state tree of South Carolina is the palmetto, the magnolia is a sentimental favorite of many residents because of its distinctive glossy leaves and large white blossoms. Included on the grounds is a combined administrative-educational building next to the sanctuary, and a large cemetery that extends behind the parking lot and sanctuary containing the remains of generations of Salem’s members.

The current brick building is located on spacious grounds in the Fairfield County countryside. Salem is an appropriate name for the church because the setting is peaceful and verdant. As one pulls into the driveway and looks up to the brick sanctuary, the lovely magnolia tree may be seen to the right of the building (as of 2013). Though the state tree of South Carolina is the palmetto, the magnolia is a sentimental favorite of many residents because of its distinctive glossy leaves and large white blossoms. Included on the grounds is a combined administrative-educational building next to the sanctuary, and a large cemetery that extends behind the parking lot and sanctuary containing the remains of generations of Salem’s members.

Barry Waugh

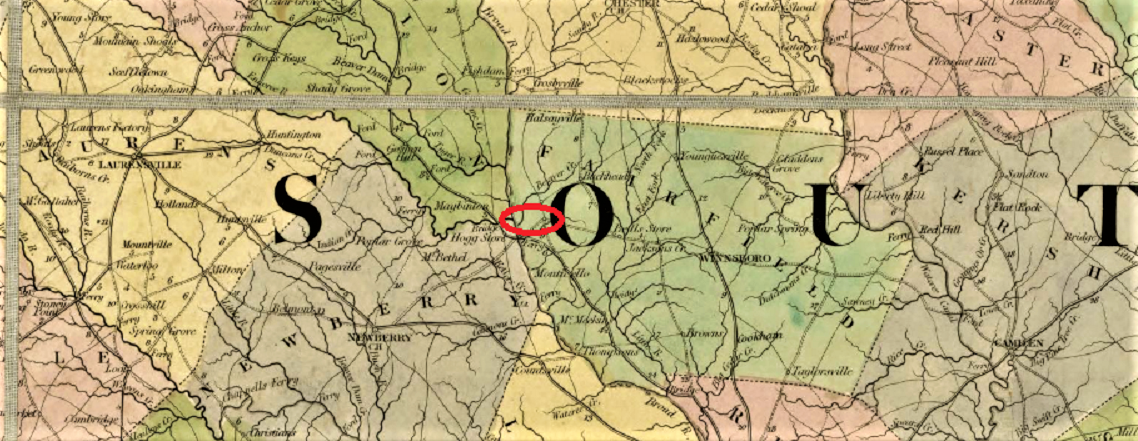

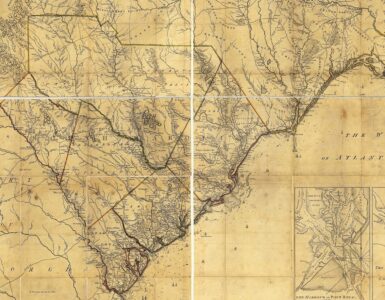

Sources—The header map shows the approximate location of Salem Church on a map from the Library of Congress dated 1839 and published in London; the church is just east of the Broad River and a bit north of SC Highway 34. The photographs were taken in the spring of 2013 by the author. The bulletin cover scan was provided by the P.C.A. Historical Center, Wayne Sparkman, Director. The published sources include: Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its Organization A. D. 1789 to A. D. 1820 Inclusive, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publications, c. 1847; F. D. Jones and W. H. Mills, History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina Since 1850, Columbia: Synod of South Carolina, 1926, pp. 673-75; and George Howe, History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina, 2 vols., Columbia: Duffie & Chapman, 1870; Columbia: W. J. Duffie, 1883, 2:264, 265, 361, 504-506, and 668. For information on First Church in Columbia, see David B. Calhoun’s, The Glory of the Lord Risen Upon It: First Presbyterian Church, Columbia, South Carolina, 1795-1995, pages 21-22.