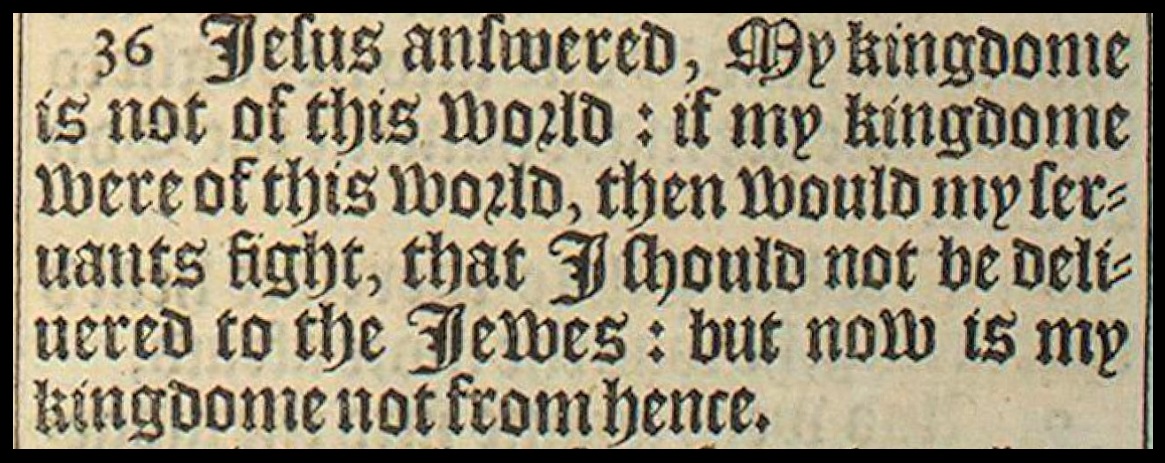

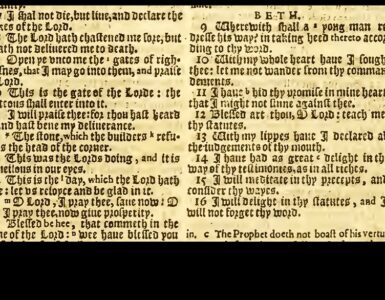

The following sermon was preached by Rev. S. Beach Jones, D. D., 1867. The header image shows the first edition King James Version text for the sermon, John 18:36.

Barry Waugh

It is scarcely necessary to remind you of the occasion on which John 18:36 was uttered. To excite the jealousy and fear of the Roman Governor, and to array his power against Jesus of Nazareth, the Jewish rulers charged him with disloyalty to the civil government; inasmuch as he claimed to be the founder and sovereign of a new kingdom. Upon being asked by the Governor, whether this charge were true, Jesus did not deny his claim to kingship. He was indeed a King; and he had founded a Kingdom; but it was not such a kingdom as earthly potentates need fear. From all kingdoms then existing, or which had ever existed, his was wholly distinct in its nature, and wholly diverse in its form, its mode of administration, and its aims; so distinct and so diverse, that it could occupy the same territory and embrace the same subjects with the kingdoms of this world, without interference, confusion, or collision.

Our Lord did not deem it necessary on this occasion formally to define the precise nature, or ultimate ends, of his Kingdom. He simply announced its unworldly character; leaving it to the Governor to infer, what, under the circumstances, it was most important to know; namely, that there need be no jealousy and no hostility between the civil government and a Kingdom which was not of this world; since between the two there could be no legitimate rivalry.

Without attempting, at this time, to dwell upon the unique character of Christ’s Kingdom, I propose to present for your consideration some of the manifold lessons suggested by the words, “My Kingdom is not of this world.” In doing this, I cannot but evolve the great truths respecting the spiritual nature of this Kingdom, and its exclusive subjection to its Divine King. We shall learn, that while not antagonistic to the kingdoms of this world, Christ’s Kingdom in its essential nature and fundamental characteristics is their very opposite. That what they are, his is not. What his is, they are not; and, from the nature of the case, cannot be. What they aim to do, can never lawfully be the aim of his Kingdom. What his seeks to effect, they can never achieve. Their respective spheres are as different, as is their origin and their duration.

From the great truth announced in our text, both Church and State may learn to circumscribe their respective domains, by limits appropriate to their nature and ultimate ends. It is a significant and most instructive fact, that in laying the foundation of the Christian Church, Christ should have done so, without in any way invoking the aid, or employing the agency of the State. It is not less significant, that his inspired Apostles—whose authority he has taught us to revere equally with his own—did in this respect imitate his example. We look in vain through the records of the New Testament for a single declaration inculcating either the necessity, or expediency, of countenance or co-operation, on the part of the State. The idea is not even implied, either in the acts, or in the teachings of the Apostles. Had the assistance of the State been necessary, or even desirable, for the welfare of his Kingdom, it had been infinitely easy for the Son of God to secure it. He was the Providential Governor of the world, the Supreme Ruler of nations; and, as such, could so have adjusted their affairs and controlled their hearts, that from the very outset, the powers of the world should have allied themselves to his cause, by assuming a fostering care of his Church. In founding the Jewish Church he did unite Church and State so intimately, that it is difficult to define the boundaries of each. Why he did so in this case, I cannot pause to show; though his designs are far from mysterious, or inscrutable. It is enough now to note the simple fact, that while in the one case civil authority and power was enlisted in the service of his Church, in the other it was scrupulously ignored and discarded. All that Christ asked, or authorized his ministers to ask of earthly powers was simple protection from interference and violence; just such protection as States are bound to vouchsafe to all their subjects, who prove obedient to civil laws.

Need I remind you, that so long as the Church continued to prosecute its great mission in strict independence of the State, its most signal triumphs were achieved? Though resisted by Jewish and Pagan powers, though subjected to successive and relentless persecutions, it multiplied its conquests, until at the close of the third century the religion of the despised Nazarenes had become the predominant faith of a large part of the Roman Empire.

Can we reasonably doubt, that one reason why the Head of the Church refused to avail himself of the patronage of the State was to furnish to the world one credential affirming its Divine origin and mission? If, without the aid of civil authority and despite all its opposition and cruel violence, the religion of the Gospel proved sufficient to undermine and supplant the time-honored religions of the most enlightened heathen nations; then, indeed, might men understand that the Church of Christ was “the Kingdom of God;” as they could not have seen and felt this truth, had the State professed a Christian creed, and lent its power to its maintenance and propagation.

But, in addition to his thus furnishing one credential of the divinity of the Gospel, the Head of the Church has taught both Church and State another great lesson, by the Church’s independence of the State for the first three centuries of its history. If with materials so feeble and unpromising as those which constituted the primitive Church, and in the face of opposition such as no other system of doctrine ever encountered, the Christian Church were able steadily to advance in the world; then might the Church in all subsequent ages learn the great lesson, that it needed no patronage from the State. In the inherent power of truth, in the living exemplifications of holiness, and in the spiritual aid of its heavenly King, the Church possessed the surest pledge of her safety and ultimate triumph. The powers of the world, too, might have learned, and should have learned, not only that their hostility to this divine Kingdom must prove unavailing; but that it stood in no need of their co-operation to further its interests.

Unhappily for both Church and State these great lessons were overlooked, or soon forgotten, when Christians discovered that they had become strong enough in power to enlist the aid of the State. From the day when the first Christian Emperor of Rome became the avowed patron and ally of Christ’s Kingdom, the Church’s true glory became in a measure eclipsed. In external splendor and a certain form of power the Church of the fourth century surpassed its earlier renown; and even among evangelical men we find some, who dwell with complacency upon the fact, that under Constantine and his successors, the Kingdom of Christ was by law, established in the Roman Empire. But let anyone, whose views of Christ’s Kingdom have been formed under the light of the New Testament alone, and especially of the doctrine of our text, let anyone carefully study the history of the Church from the days of Constantine to our own, and he will feel, that in seeking, or permitting an alliance with the State, it has been guilty of a grievous defection from the Gospel standard, and has lost far more in spiritual purity and energy, than it has gained in external prosperity and power. Scarcely was the religion of the Gospel espoused by the powers of the State when Christians began to demand the propagation of their doctrines by the forces of the State. They who, while subject to Pagan persecution, had insisted that the weapons of the Church were “not carnal, but spiritual,” now employed the sword of the magistrate to extend the Kingdom of Him who had proclaimed, “My Kingdom is not of this world.” We find Arians persecuting the Orthodox, and Orthodox persecuting Arians. We read of princes compelling heathen tribes to submit to Christian baptism, or suffer the penalty of the sword. And for more than a thousand years the history of Christianized Europe is a history of incessant intermeddling of State with Church, and of Church with State. No small part of the statesmanship of Christian nations was expended in the adjustment of the claims and interests of the Church. No inconsiderable proportion of the wars which desolated European states for twelve centuries have, in one way or another, been prosecuted for the alleged welfare of Christ’s Kingdom. The crusades for the possession of the Holy Sepulcher, and the extirpation of Albigenses and Waldenses, the wars of Spain for the suppression of Protestantism in the Netherlands, and of France against her Huguenot subjects, the “Thirty Years War” in Germany, and some of the most sanguinary conflicts in Great Britain and Ireland, were waged in professed maintenance of that Kingdom, whose Sovereign had announced, “My Kingdom is not of this world; else would my servants fight.” “Put up thy sword into his place; for all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.”

So long had the Church been accustomed to call to its aid the sword of the State; so habituated had Christians become to the pernicious doctrine that States, as States, were bound to defend Christ’s cause, by punishing its enemies; that even the Reformers themselves advocated the punishment of heretics by the civil sword. Without an exception, they had learned in the bosom of the Romish Church and from a perverted interpretation of the Old Testament to treat religious heresies, as if they had been civil offences, and to apply to Christ’s spiritual Kingdom, what was only applicable to the Jewish State, in which Jehovah was as much the Civil Ruler and Lawgiver, as he was their Religious Sovereign.

Nor was it merely in suppressing heresies and punishing heretics that the Church authoritatively claimed the interposition of the State. In endless ways did it presume to prescribe to the State, what policy it should pursue in promoting religion, in advancing civil interests, and even in conducting its affairs with foreign nations.

It seems strange to us, that in all the Reformed Churches of Europe the State should have been allowed, and even invited, to prescribe and legislate for the Church. We shall be no less surprised to discover, that the Church did not scruple to dictate to the State, not only as to matters ecclesiastical, but even as to many strictly political. Even in Scotland, where the work of Reformation was more thorough than in most countries, and where the successors of the Reformers, if not the Reformers themselves, had attained more just views of the distinct provinces and functions of Church and State, even there it is manifest that their wisest and best men possessed but imperfect conceptions on this subject. Whoever reads the history of that Church will be amazed to find, that their Synods and General Assemblies deemed it entirely within their province to pronounce judgment on the political acts of their Parliament, and unasked, to counsel it, as to what course it should pursue, even in such matters as war, and peace, and civil alliances. The Westminster Assembly was not more scrupulous in its policy. We find it petitioning the Parliament of England to employ its powers in suppressing religious errors, and urging it to discountenance the toleration of Dissenters. We see that venerable body endearing its advice to the civil power, as to what course it were best to pursue in the affairs of State. The admonitory lessons and the bitter experience of three centuries have proved inadequate to enforce on Scottish Presbyterians the necessity of an entire separation of Church and State, in order for the highest prosperity of both. The very men who have been constrained by a sense of duty to Christ to withdraw from the Church established by law, insist as strenuously as any and as ever, on the obligation of the State to lend its direct aid to the maintenance and extension of the Church, and on the right of the Church to counsel and advise the State. Warned by the experience of Churches in other lands, and compelled too by imperative necessity, the framers of our Church standards, for the first time in the history of modem Presbyterianism, resolved to realize the great doctrine of the text, “My Kingdom is not of this world.” They erased from the Westminster standards whatever empowered the civil magistrate to interfere in the affairs of the Church, or in matters religious, while they inserted the explicit doctrine, “Synods and Councils are to handle, or conclude, nothing but that which is ecclesiastical; and are not to intermeddle with civil affairs, which concern the Commonwealth, unless by way of humble petition in cases extraordinary, or by way of advice for satisfaction of conscience, it they be thereunto required by the civil magistrate.”

In the practical recognition of this truth the Church of our fathers prosecuted its mission for nearly eighty years, and its external growth, and its internal prosperity, proved to the world that Zion’s King needs not the alliance of earthly potentates; and that his Kingdom will best flourish when its affairs are kept most distinct from mere secular interests. The powers of the State, too, were as little disposed to meddle with the Church, as the Church had been to interfere with the State.

The last six years have witnessed an alarming reaction from what had been deemed the settled policy both of Church and State. In defiance of the explicit prohibition of its standards, the Church has not only undertaken to “handle and conclude questions strictly political,” but so far “to intermeddle with civil affairs,” as to impose upon her members political tests, as terms of communion. She has ventured, unsolicited, to prescribe to the civil government what particular policy it was bound to pursue. She has enjoined on her members, as a sacred duty to Christ, the support of a particular policy, and threatened them with ecclesiastical penalties, if they refuse obedience to her mandates.

After so palpable a repudiation of her own Constitutional doctrine, we need not be surprised to find the State intruding into the province of the Church, by prescribing to Church courts rules for their procedure, and by virtually declaring who are, and who are not qualified to serve Christ in the ministry of the Gospel.

In keeping with these defections from what we had deemed the unalterable principles recognized in our land, are the efforts now made so to amend the Federal Constitution, as to convert it into a Christian document, and so to alter our form of government, that none but Christian men shall fill its offices. The civil Constitution is virtually to become a Christian Confession of Faith, by proclaiming Jesus Christ the rightful Sovereign of this nation, and his Gospel the supreme law of the land.

As we review the history of the Church and of European nations for fifteen hundred years, it is hard to decide, whether Church or State has most suffered by the interference of each with the affairs of the other. States have been ravaged by successive wars, under the pretext of helping the Church. Diplomacy and statesmanship have been employed in settling the affairs of Christ’s Kingdom, when they should have been devoted to the material interests of the State. The Church, in turn, has been more or less secularized in her spirit and aims. Her energies have been divided between secular and spiritual affairs. Her ministers have lost much of that moral power, which can only invest such as are known to be devoted to the sacred interests of a holy and spiritual Kingdom. We can readily discover this in the histories of foreign Churches; not only Romish, but Protestant, not only Prelatical, but Presbyterian. We may not so clearly discover like fruits in our country, because the seeds of evil have scarce had time to produce their fruit. But this we do know, and this we should know, that no small portion of the time spent by the last five General Assemblies of the Church, was devoted to the consideration of matters which their Constitution has declared to be pertinent to the State alone; that, as a result of its political deliverances, the unity of the body has been destroyed, a lamentable schism has been effected, and an alarming disintegration threatened; that by allying itself to a political party, and proclaiming its adhesion to political tenets—as to which the people of the land are nearly equally divided—multitudes within the pale of the Church have become alienated from its ministry, and not a few have withdrawn from its ministrations, while multitudes outside of the Church, who might otherwise have been drawn within its fold, have learned to view with suspicion and dislike a body, which has virtually proclaimed itself an adjunct to a mere political faction.

For so flagrant an apostacy from its own clearly pronounced standards and their former professions, the apologists for this defection have urged various excuses. The most common have been, the precedents furnished by Church History. I will not stop to notice such a defense. Church Councils furnish precedents for any form of error a man may adopt, or any kind of iniquity he may have perpetrated. Even the comparatively pure Church of Scotland furnishes precedents for political intermeddling, which the most ardent of our political Churchmen would shrink from following.

A far more specious apology for the revolutionary course of the Church is, that the Church courts did not presume to settle the political questions involved, but merely a moral question, which, as the great moral Teacher, the Church had a right and was bound to decide for her members. If this be true of the questions adjudicated by our late Assemblies, then we must justify the most flagrant acts of spiritual despotism which disgrace the records of the Church. What but the moral questions involved did the Inquisition pretend to decide, when it pronounced sentence on its hapless victims, and delivered them up to the magistrate to be burnt? What but a moral question did the Popes of Rome pretend to decide, when they urged upon Catholic princes the duty of suppressing heresy with the sword? And have not the former persecutions of Dissenters by the Prelates of England, and of the Romanists by the Presbyterians of Scotland, been justified by a like plea?

This pretext will never abide the test of the Gospel. The example, as well as the recorded declarations of its Divine Author, proves its fallacy. Who can deny, that when “one of the company said unto Jesus, Master, speak to my brother, that he may divide the inheritance with me,” there was a very important moral question involved? One or the other, or it may be both of the brothers, had perpetrated, or was disposed to perpetrate a moral wrong, and who so competent to sit in judgment on a moral question as He, who as God, was the author of the moral law, as well as of the civil and ceremonial law of the Jewish people? Yet, what was his answer to this appeal, which seemingly was so reasonable? “Man, who made me a judge, or a divider over you?” Why this refusal to exercise his authority in the settlement of a moral question? Because that question, though it did involve moral elements, was mainly a civil question, falling properly within the province of the civil law and its officers. Jesus was the minister of another Kingdom, and he would not embarrass himself, or his cause by needless complications with matters foreign to his spiritual work; and herein he designed to teach the officers of his Kingdom to beware of all such insidious entanglements with secular affairs; to maintain a rigid separation between his Kingdom and those of this world.

To minds that have never been familiar with the history of the Church, nor clearly apprehended the spiritual nature of Christ’s kingdom, or who have adopted erroneous interpretations of those prophecies which announce the ultimate subjection of all nations to the scepter of Emmanuel, there is a marvelous seductiveness and fascination in the idea of a State formally professing its allegiance to Christ, and of Kings and Queens, as such, becoming “nursing fathers and mothers” to his Church. Without stopping to show, how all the prophetic predictions of the Church’s final triumphs may be realized, without this fusion and confusion of Church and State, let me advert to undeniable facts. The very States which do most formally, distinctly, and fully profess a Christian creed; the States where religion is most patronized and enforced by “the powers that be,” are of all others the most demoralized, while the Church is most deeply degraded and corrupted. Compare the moral character and material condition of Spain and of the Roman States with our own; compare the religious condition of Spain and of Italy with our own; and what a lesson does it teach, on the subject of so-called “Christian Governments!”

Is it said that the moral and political condition of the State, and the spiritual condition of the Church in these instances, is to be ascribed to the form of religion there professed? Then let us turn to Protestant States. In England, the Church is established by law, and the Protestant faith a part of the civil constitution. Until a period comparatively recent, no man could fill a civil, or military office, without partaking of the Lord’s supper, according to the ritual of the Church of England. Does any evangelical Christian believe, that Christ’s cause, or the best interests of the State, were promoted by such governmental religion?

There was a time when the State of Massachusetts was a virtual theocracy. The State regulated the Church; and the Church the State. No citizen was eligible to office in the State, unless he were first a member of the Church. And what is Massachusetts now? And what is the condition of her churches? In no part of this land have infidelity and soul-destructive heresy so rioted, as in that very commonwealth where the same system was long maintained, which many are now striving to establish over our whole land.

No, no; this is not Christ’s plan for Christianizing a State. He has shewed us a better way; and it is the only sure way. His kingdom, he tells us, is “like leaven, which a woman took and hid in three measures of meal, until the whole was leavened.” Is there no special design in the selection of this simile? How does leaven work on the mass into which it is introduced? Why it gently insinuates its elements until it permeates the whole, and transforms its nature. The State is not to be molded by an external pressure on the part of the Church, but by a process akin to the chemical agencies of nature. The Church is not to manipulate the State, as the potter fashions his vessel. It must labor to imbue all whom it can reach with the spirit of the Gospel; to teach all to regulate their conduct in all the relations of life by the precepts of the Gospel. In this way, and in this alone, can a State become Christianized; and when its subjects have thus become Christians, then will civil laws be framed in harmony with the moral laws of Christ’s kingdom; and then will political measures be such as will best serve both Church and State. The reformation of States, like the reformation of individuals, must commence within, and work outwardly; and not begin without and extend inwardly. Legislation may be professedly Christian, and at the same time flagrantly unchristian in character; and, on the other hand, legislation may make no proclamation of its Christian character, and yet be eminently Christian in its spirit and fruits. A magistrate may loudly proclaim his faith in the Gospel, and his allegiance to Christ, and yet be an arrant hypocrite and a wicked despot; while another may be reticent of his Christianity, and still serve Christ by a policy approved by his Gospel. The State may, and it should, govern its subjects and regulate its affairs in the spirit of the gospel, and in harmony with its moral precepts; but it should show its Christianity by its acts; rather than by religious symbols. It is no part of its functions to profess a Christian creed. This is the appropriate office of the Church. She is to be Christ’s witness before the world. Such is Christ’s own arrangements, and wherever it has been disregarded, and the Divine order reversed, both Church and State have been the sufferers. There may be a greater external display of religion, but there will be less of vital godliness.

We may further learn from our text, that in her organic and official action the Church should be governed by the statutes of her King; and her aims and objects should be exclusively those which he has prescribed.

Nearly every schism which has marred the unity of the Church may be traced to an assumption, on the part of the Church, of a power never delegated by her Divine Head; a claim to legislate, where Christ has not authorized legislation. But for this, we should not see Christendom divided between Catholics and Protestants. But for this, the Dissenters of England would not outnumber the members of the Establishment; nor the Seceders of Scotland its ancient Kirk. But for this, the Presbyterian Church of this country would never have been rent in twain; nor now be threatened with disintegration. The subjects upon which the Church is authorized to legislate are comparatively few. If ministers individually, or as Church Courts collectively, would command the Christian conscience of the people; they must not only plead Christ’s authority; but be able to adduce it, by citing the explicit, or clearly implied, commands of their Lord. The more intelligent Christians become, the more they study and interpret for themselves the oracles of God, the more dangerous will it be for Church courts to legislate beyond the warrant of the Gospel; and the more difficult will it be for preachers to invest the mere “commandments of men” with the sanctity of “the doctrines” of God. This undoubtedly is one great reason why in Scotland, and in our own land, the Presbyterian Church has so often been rent by schism. Presbyterians are too intelligent, too tenacious of the exclusive authority of Christ to legislate for his Church, passively to submit to legislation which transcends the limits of their divine charter. Hence, if there be a Church in the world which is bound to adhere closely to its constitution, that Church is the Presbyterian. Its members will submit to no lawgiver or King, but Jesus. Especially will this hold true when Church courts venture to bind the conscience by deliverances and laws, which their very standards of faith forbid them to enact. A so-called “venerable court” will command our veneration, only so long and so far, as it restricts itself to its appropriate work; and governs itself by divine statutes. The moment an ecclesiastical council resolves itself into a political assembly, that moment it loses its character as a “venerable court;” and is received and treated by right-minded men with even less respect, than a convention of avowed politicians.

The same is true of all ministers, who convert their pulpits into political rostrums. What is it which invests the preacher of the Gospel with sanctity, and his discourses with authority? It is the fact, that he claims to stand before his hearers as an ambassador from the King of Kings; and to deliver a message from Him. So long as his messages are manifestly divine; so long as he can furnish credentials of their divine authority, by the attestations of the Bible itself; so long will he speak with power to all who revere the Gospel. But when, as a minister of the Gospel, he adventures to harangue his hearers on matters political, he ceases to be Christ’s ambassador to them: for he can furnish no warrant from Christ for what he has proclaimed. It is simply his counsel, not Christ’s message; and all men have a right to trust him and his utterances as they would any mere politician, or any newspaper article.

But not only do such men cease to be regarded with the deference rendered to a faithful ambassador of Christ; they do infinite evil to the cause of Christ, and to the sacred office of the ministry. There is enmity enough to the Gospel in every heart, and in every community, without gratuitously provoking it. Yet it is provoked, wherever a minister of “the everlasting Gospel” becomes a political teacher, and takes advantage of his pulpit to propagate his sentiments. A few may be gratified at such a perversion of the divine office because it serves party purposes, but even less will respect the preacher who has thus merged the minister in the politician.

There is perhaps, no Church in our land in which political discourses have been delivered, where fruits of bitterness are not already maturing. There are lines of division, clearly marked, running through thousands of congregations, that have not, as yet, been formally divided. There are multitudes who once were stated attendants at the sanctuary, but who now never enter it. There are multitudes who have forsaken Protestant churches, in the hope of finding quietude in the bosom of the Catholic. Within the past month, fifty-five professed Protestants were by baptism admitted into a single Catholic church in a neighboring city. That the Protestant ministry has been lowered in public esteem and confidence within the last six years, is as certain, as that such a ministry exists, and has busied itself with matters foreign to their sacred functions. What could better exemplify this humiliating truth, than the fact that during the late sectional war the clergy, for the first time in the history of Christian nations, were held liable to the military draft, equally with other citizens? Many years must elapse, and a mighty change be seen in the conduct of the clergy, ere they can recover the commanding position they once occupied.

Every unsophisticated reader of the Gospel learns from its teachings, that if there be one class of men, who, more than all others, should exemplify the spirit of peace, it is the minister of “the Prince of Peace;” that if any agency on earth is under obligation to compose strife in a distracted land, it is that of the kingdom of “righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.” The world itself expects, and has a right to expect, that the official servants of Christ, above all others, will bear in mind their Master’s proclamation: “Blessed are the peacemakers; for they shall be called the children of God.” Is it to be wondered at, then, that the clergy of the land, as a class, have lost much of their moral power over the public mind, when their recent practice is contrasted with the requirements of their religion? Instead of “peacemakers,” many of them have proved the fiercest and most sanguinary advocates of war. Instead of allaying animosities, many courts of the Church have done more than political conventions to irritate, exasperate, and embitter existing feuds. Every discriminating reader of the Gospel discovers, that while Christians, in the capacity of citizens, owe duties to their civil governments; yet to Christ’s kingdom they owe a still more important service. Its interests should be paramount in their affections. Especially does this hold true of that class of Christ’s subjects, who by their very office profess to be wholly consecrated to his service. But where Christian ministers are drawn into the vortex of political turmoil, they are under the strongest temptation to reverse the divine order of things; and to exalt secular above spiritual interests. So, it ever was in days of old, when cardinals and bishops were the prime ministers and chancellors of Kings. So, to some extent, has it been of late in our land. Many a minister has evinced a fervency and intensity of zeal in behalf of civil interests and military movements, which he was never known to discover in matters spiritual and ecclesiastical. Unconsciously to themselves, Church courts have reversed the relative importance of the interests of Christ’s kingdom, and those of the State, by sacrificing the former to secure what they regard as the true interests of the latter. Rather than forego their deliverances on matters political, they resolved to risk the division of a once united church. By this devotion to affairs strictly secular, they have hopelessly rent the Church, by driving off from their communion a body of Christians, who, in point of piety, of self-sacrificing labor, and of attachment to the doctrines and order of the Church, are the peers of any ecclesiastical communion in Christendom. Nor is this all. Having driven off into a justifiable schism those whom they once acknowledged to be the soundest portion of the Presbyterian Church and having done this simply and solely for reasons political; we now see them making overtures for re-union with a body, from which they once separated, because of their alleged defection from the doctrinal and governmental standards of the Church. None who are familiar with the history of this movement can for a moment doubt that its real cause is as purely a political affinity, as the other was a political antagonism. Verily, before the Church can regain her former commanding position, as an institution purely spiritual, a “kingdom not of this world,” she must purge out the political leaven that has so largely pervaded her, repudiate her recent policy, and restrict herself to the work allotted her by her divine Lord.—And, as one of the great lessons taught by history, it must be borne in mind that if the Church adventures to intermeddle with the affairs of State, the State inevitably will invade the province of the Church. One great reason, if not the reason, why both in Scotland and in England the Church’s independence of the State was resisted and refused, is found in the fact, that ministers and church courts were disposed to intermeddle with the affairs of the State. It should not be forgotten that the interference of the civil magistrates, or rather of military officers as their instruments, in the affairs of the Church, did not precede, but followed the Church’s interference with matters political. If, therefore, the Church would enjoy spiritual independence, she must allow the State to maintain an exclusive control over her own affairs.

My limits forbid me to educe and enforce many of the great lessons suggested by our text. Ere I close, however, I may remind you, that if Christ’s Kingdom be not of this world, then we may see how incongruous in such a Kingdom is the carnal policy and finesse, by which worldly kingdoms are sustained and advanced.

As the world begins to feel the leavening influence of the Church, and in a measure to become assimilated to it, the Church itself becomes conformed to the world. Hence the danger of resorting to worldly expedients for promoting its ends. This has been abundantly exemplified of late years in our Church courts, and especially in our supreme Judicatory. Much which was formerly done only in open court, is now contrived and digested in secret caucus. That which in civil legislatures is styled “wire-pulling” and “log-rolling,” has been introduced into the courts of Christ’s house, and to such unhallowed maneuvering and secret management, may not a few of our recent troubles be traced. The temptation to this sin increases, as the wealth of the Church accumulates. Where funds are to be managed and offices to be disposed of, there will be in the Church the same kind of danger to its purity, that all true patriots discover in the State. Nothing can save the Church from contamination, but distinct views and a deep sense of the spiritual, unworldly character of Christ’s Kingdom. In such a Kingdom, all the maxims and measures of a low expediency are out of place, and inimical to its true interests. By the immutable statutes of Christ’s holy Law must the officers of Christ’s House endeavor to manage all its affairs. Ingenuousness, openness, uprightness must characterize the doings of Christian courts, if they would deserve the name of “Venerable courts,” by commanding the veneration of the world, and of the Christian body itself.

And, finally, we may learn, that the Church system which gives most prominence to what is spiritual, and least depends on the mere externals of religion, is most in harmony with the. character of Christ’s Kingdom.

By many minds the power and glory of a Church is measured by what is visible to the senses, and attractive to the natural tastes of men. Hence, we so often hear of the “imposing rites,” the “impressive ceremonials” of certain churches. Hence, too, many imaginative minds find so little aliment in the simple services of our own Church, that they forsake it for such as will minister to their aesthetic enjoyment. Had such persons lived in the days of Christ and his Apostles, there is little doubt that they would have preferred the gorgeous ritual of Judaism, to the simple and more spiritual service of Christ’s house.

Let it never be forgotten by the citizens of Christ’s Kingdom, that when their King was asked, “When the Kingdom of God should come”; his answer was, “The Kingdom of God cometh not with observation; for behold the Kingdom of God is within you.” That Kingdom was not one of outward show or parade. Its splendor was not such as captivates the senses. But it was a Kingdom whose power and glory lay in the graces of the heart, and in the fruits of those graces in the life. Let it never be forgotten that the Apostle, who more than all his fellows, could appreciate what was attractive to a cultivated taste, was the Apostle who announced to the Christians of the Imperial and magnificent city of Rome, “The Kingdom of God is not meat and drink; but righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.” It does not consist in ceremonial observances; its glory is not the glory of gorgeous vestments, or dramatic scenes, or melting music, or awe-inspiring temples, but in the beauty of living piety, “righteousness” towards God, “peace” towards men, and “joy in the Holy Ghost.”

The clearer our conceptions of the meaning of our text, the more fully we apprehend the spiritual nature and the ultimate designs of this divine Kingdom, the less likely shall we be to hanker after those external displays which appeal to the taste, or gratify the imagination, without enlightening the understanding, or purifying and elevating the heart. The more completely Christ’s Kingdom is established within us, the less shall we be imposed upon by “the imposing ceremonies,” which man, and not the Son of God, has introduced into his Church.