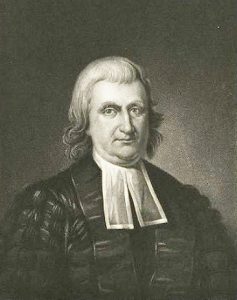

The congregation for this sermon by John Witherspoon may have been students in the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) based on Witherspoon’s comment— “Perhaps, however, there are some circumstances that render it peculiarly proper for this auditory. Young persons are very apt to cherish vast and boundless desires as to outward things; and having not yet experienced the deceitfulness of the world, are apt to entertain excessive and extravagant hopes.” Witherspoon’s works have been published in sets of nine, three, four, and possibly two volumes. He is known primarily for his participation in the American Revolution as the only minister to sign the Declaration of Independence, but he was a respected Presbyterian minister who was selected to open the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America when it convened in 1789. Failing health led to his surrendering the podium to his friend and biographer, John Rodgers. His third area of influence was as president and professor at the College of New Jersey. If he ever wore a tri-cornered hat, the three corners could signify his callings as minister, educator, and founding father.

The congregation for this sermon by John Witherspoon may have been students in the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) based on Witherspoon’s comment— “Perhaps, however, there are some circumstances that render it peculiarly proper for this auditory. Young persons are very apt to cherish vast and boundless desires as to outward things; and having not yet experienced the deceitfulness of the world, are apt to entertain excessive and extravagant hopes.” Witherspoon’s works have been published in sets of nine, three, four, and possibly two volumes. He is known primarily for his participation in the American Revolution as the only minister to sign the Declaration of Independence, but he was a respected Presbyterian minister who was selected to open the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America when it convened in 1789. Failing health led to his surrendering the podium to his friend and biographer, John Rodgers. His third area of influence was as president and professor at the College of New Jersey. If he ever wore a tri-cornered hat, the three corners could signify his callings as minister, educator, and founding father.

The sermon transcribed below comes from pages 345-59 of the second of three volumes titled, The Works of the Rev. John Witherspoon, D.D, LL. D. Late President of the College, at Princeton New-Jersey. To Which is Prefixed an Account of the Author’s Life, in a Sermon occasioned by his Death, by the Rev. Dr. John Rodgers, of New York in Three Volumes, Philadelphia: Printed and Published by William W. Woodward, No. 17, 1800.

Note that the outline is missing some points. Also, there are two biographies on this site about men named John Witherspoon. The second John Witherspoon is the current subject’s grandson.

Barry Waugh

On the PURITY of the HEART.

A SERMON.

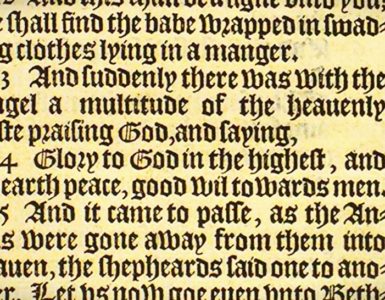

Proverbs 30:7-9

Two things have I required of thee, deny me them not before I die: remove far from me vanity and lies; give me neither poverty nor riches; feed me with food convenient for me, lest I be full and deny thee, and say, who is the Lord? or lest I be poor and steal, and take the name of my God in vain.—

My Brethren,

OUR dependent condition as creatures, and much more our dangerous condition as sinners, exposed to daily temptation, renders prayer a duty of the most absolute necessity. You must all be sensible, how frequent and pressing the exhortations to it are in the holy scriptures. And, indeed, there cannot be a better evidence of a right temper of mind, than a habitual disposition to the exercise of this duty.

But as prayer is a necessary duty, we ought to give the greater attention to the manner in which it is performed. We ought to ask only for such things as are truly safe and useful. We ought also to offer up our prayers with importunity, or reserve, according to the nature and comparative importance of those blessings we desire to obtain. All our wants are perfectly known to God; he is also the best judge of what is fit for us, and therefore, our petitions should be well weighed, and expressed in such terms, as, at the same time that they intimate our desires, leave much to himself, as to the measure and manner of satisfying them.

We have an excellent example of this pious and prudent conduct, in the prayer of the prophet Agur, just read in your hearing. All his requests are summed up in two general heads. These he seems to insist upon, as absolutely necessary to ask, with that humble, holy confidence, which is founded on the divine promise, that if we ask anything agreeable to his will, he heareth us. He seems also to ask them, as what would fully satisfy him, and be sufficient for the comfort of the present life, and the happiness of the life to come. “Two things,” says he, “have I required of thee, deny me them not before,” or, as it ought rather to be translated, “until I die.”

These two requests are conceived in the following terms. “Remove far from me vanity and lies, give me neither poverty nor riches.” The first, viz. “remove far from me vanity and lies,” evidently relates to the temper of his mind, and the state of his soul. The second, viz. “give me neither poverty nor riches,” relates to his outward condition or circumstances in the present life. There are two things in the general structure of this comprehensive prayer, that merit your particular attention. First, the order of his request; beginning with what is of most importance, the temper of his mind, and his hope towards God; and then adding, as but deserving the second place, what related to his present accommodation.

Secondly, The connection of his requests. The choice he makes as to his temporal condition, is in immediate and direct subserviency to his sanctification. This is plain from the arguments with which he presses, or the reasons which he assigns for his second petition, ”Give mc neither poverty nor riches, lest I be full and deny thee, and say, who is the Lord? or lest I be poor and steal, and take the name of my God in vain.”

My brethren, I am persuaded that this subject can hardly be, at any time, unreasonable to a Christian assembly, as our misplaced, excessive, and unreasonable desires are the greatest enemies to our progress in holiness, as well as to our comfort and peace. Perhaps, however, there are some circumstances that render it peculiarly proper for this auditory. Young persons are very apt to cherish vast and boundless desires as to outward things; and having not yet experienced the deceitfulness of the world, are apt to entertain excessive and extravagant hopes. The truth is, rich and poor, young and old, may here receive a lesson of the utmost moment.

Let me therefore intreat your attention, while I endeavor to open and improve this passage of the holy scriptures; beginning, at this time, with the first request—”Remove far from me vanity and lies.”

In discoursing on which, 1 will endeavor,

FIRST. To explain the import of it, or shew at what it chiefly points, and to what it may be supposed to extend.

SECOND. Apply the subject for your instruction and direction.

FIRST. I am to explain the import of the prophet’s prayer, or shew at what it chiefly points, and to what it may be supposed to extend, in the petition, “Remove far from me vanity and lies.” The word vanity, especially when it is joined, as it is frequently in scripture, with lying, or lies, is of a very large and comprehensive signification. The word in the original, translated vanity, properly signifies lightness or emptiness; and lies signify falsehood, in opposition to truth.

I imagine we shall have a clear conception, both of the meaning and force of this phrase, if we make the following remark: God himself is the great fountain of life and experience; the great I AM, as he emphatically styles himself to Moses; the original and the only reality, if I may so speak. All other beings have only a dependent and precarious existence; so that the creation itself, though his own work, compared to him, is vanity. “Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.” Therefore, in a particular manner, the word is often used to denote the folly of all idolatrous worship; or the giving the respect and honor to anything else, which is due to God alone. “They have moved me to jealousy with that which is not God, they have provoked me to anger with their vanities. Are there any among the vanities of the Gentiles, that can cause rain; or can the heavens give flowers, art thou not he, O Lord our God?”

Sometimes it is used to denote the folly or unprofitableness of any vice, and particularly of an ill-founded conceit of ourselves, as well as of all fraud and dissimulation, in word or action. So that this prayer for our souls, short as it appears to be, when considered in its full extent, will be found to contain a great variety of important matter.—This I shall endeavor to give you a brief account of, under the following particulars.

First. We are hereby taught to pray, that we may be preserved by divine grace, from all false and erroneous principles in religion; so as we may neither be deceived by them ourselves, nor any way instrumental in deceiving others. This, by what has been said of the use of the words in scripture, appears to be implied in the request, and it is of more moment than some are willing to allow. The understanding being the leading faculty, an error there, spreads its unhappy influence through the whole temper and life. Whereas, on the contrary, light in the mind, produces fidelity and security in the conscience, and tenderness in the conversation. You may observe, that through the whole history of the Old Testament, idolatry, or a departure from the knowledge and worship of the true God, is the leading sin, and the fruitful source of every other vicious practice. We sometimes, indeed, seem to stand astonished at the excessive proneness of the ancient Jews to this sin. But we need only a little reflection to discover, that an evil heart of unbelief continues the same at bottom, and daily produces the like dangerous effects. How prone have men been in all ages, to depart from the simplicity of the truth! In how many different shapes have they perverted it! One age, or one country, has been polluted by one error; and another by an opposite; impelled by the unstable and irregular fancies of men of corrupt minds. In the last age, the great theme of the carnal reasoner was, to attempt to expose the scripture doctrine of God’s certain knowledge, and precise ordination of all events; and in this, fate and necessity, have become the strong hold of infidelity, and are embraced, or seem to be embraced, by every enemy of true religion without exception. Error, shifting its ground, indeed, is but natural; for lying vanities are innumerable; but the true God is the same “yesterday, today, and forever.”

At this very time, how abounding and prevalent is infidelity, calling in question the most important and fundamental principles, both of natural and revealed religion! And how properly is this described, by the expression in the text, vanity and lies; for it always takes its rise from the pride and vanity of the human heart? Sometimes a pride of understanding, which aspires to pass judgment on things far above its reach, and condemn things long before they are examined and understood. Sometimes, also, from a pride of heart, or self-sufficiency, that is unable to endure the humbling and mortifying view, given us in scripture, of our character and state. Oh how readily do men turn aside from the truth! With what greediness do they drink in the flattering but deceptive poison! Need I point out to you the fatal effect of such principles taking place? It loosens the obligations to obedience, takes off the edge of the reproofs of conscience, and thus removing restraints, leaves men, in the emphatical language of the holy scripture, “to walk in the ways of their own hearts, and in the fight of their own eyes.”

But in this request, “remove far from me vanity and lies,” I would not have you confine your views to the most gross infidelity and avowed opposition to God. Pray also, that you may be preserved from error, or mistake of any kind; but especially such as have the greatest influence on the substance of religion.

A clear apprehension of the holy nature, and righteous government of God—the infinite evil of sin—the foundation of our peace in the blood of the atonement—and the renewing of our natures by the Holy Ghost, seem to me absolutely necessary to true and undefiled religion. And they are the truths, which particularly serve to exalt the Creator, and lay the creature in the dust. When, therefore, we consider how grateful to corrupt nature everything is, that tends to foster pride—to create security, and set the mind at ease, in the indulgence of sin: we must be sensible of how great importance it is, to pray for divine direction, and divine preservation. Nothing is more dangerous to men than confidence and presumption—nothing more useful in faith and practice, than humility and self-denial.

Second. This prayer implies a desire that we may be preserved from setting our affections on such objects, as are but vain and unsatisfying, and will, in the end, disappoint our expectation. I take this to be not only a part, but a very important part of the prophet’s meaning. The world is the great source of temptation; the powerful and unhappy influence of which we may daily see; or rather, all of us daily and sensibly feel. That it possesses the fancy, misleads the judgment, inflames the affections, consumes the time, and ruins the soul, but these present enjoyments, of which the wisest of men, after a full trial of them, hath left us their character vanity of vanities.

I am sensible that I have now entered upon a subject, which is far from being difficult to enlarge upon, and yet perhaps, very difficult to treat with propriety, or in such a manner, as to have the intended effect. There is nothing more easy than, in a bold declamatory way, to draw pictures of the vanity of human life. It hath been done by thousands, when, after all their broken schemes, and disappointed views, they have just suffered shipwreck upon the coast of the enchanted land of hope. But from such men we may expect to hear the language of despair, rather than of experience; and as it is too late for the instruction of the sufferers, so it very rarely has any effect in warning ethers to avoid the danger. What I would, therefore, willingly attempt, is, to consider this matter in a sober scriptural light; if so be, that it may please God to carry conviction to our hearts, and make it truly useful, both to speaker and hearers.

Let me, therefore, my brethren, point out to you, precisely, wherein the vanity of the world lieth. The world, in itself, is the workmanship of God, and everything that is done in it, is by his ordination, or permission of God. As such, it is good, and may be used in subserviency to his honor, and our own peace. But through the corruption of our nature, the creature becomes the rival and competitor of the Creator for our hearts.—When we place our supreme happiness upon it, instead of making it a means of leading us to God, then its inherent vanity immediately appears.—When men allow themselves in the indulgence of vicious pleasures, how justly may they be called vanity and lies? They are smiling and inviting to appearance, but how dreadful and destructive in their effects?

Think on the unhappy consequences, of dishonesty and fraud. ”Bread of deceit is sweet to a man, but afterwards his mouth shall be filled with gravel.”—You may also see, in innumerable passages of scripture, that oppression of others, as it is a sin of the deepest dye, so it is often remarkably overtaken, and punished in the course of Providence, even in the present life. Envy thou not the “oppressor, and choose none of his ways; for the froward is an abomination to the Lord, but his secret is with the righteous. The curse of the Lord is in the house of the wicked, but he blesses the habitation of the just.”

But there is something more in this request, than being preserved from practices directly vicious; for the setting of our hearts upon worldly things, and making them our chief portion and delight, is certainly seeking after vanity and lies. They are far from affording that happiness and peace, which they demand of them, and expect from them. “A little that a righteous man hath, is better than the riches of many wicked.” Can there be anything more conformable to experience, than that strong expression—”Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies, thou anointest my head with oil, my cup runneth over.” You may also find in the word of God, many warnings of the folly of those, who travel in the path of ambition, and put their trust in man. “Surely men of low degree are vanity, and men of high degree are a lie. Put not your trust in princes, nor in the son of man, in whom there is no help. Happy is he that hath the God of Jacob for his help, whose hope is in the Lord his God.” But the most comprehensive remark of all, upon this subject is, that human life itself is so exceedingly precarious, that it must write “vanity and emptiness” on everything, the possession and use of which is confined to the present state. “Behold thou hast made my days as a hand-breadth.” What a striking picture does our Lord draw of the vanity of human happiness, in that parable of the ground of the rich man, which brought forth plentifully? “And he thought within himself, saying, what shall I do, because I have no room where to bestow my fruits?”—And while this man is sedulously employed in making provision for a long and happy life, “God said unto him, thou fool, this night shall thy soul be required of thee, then whose shall those things be, which thou hast provided!”

The whole of the preceding representations may be summed up in this excellent sentence of the wise man: “The wicked worketh a deceitful work; but to him that soweth righteously shall be a sure reward.”

Now, my brethren, need I add, how prone we are to be led astray, in a greater or less degree, by such “vanity and lies?”—I do not insist upon the many victims, which, in every age, have been seen to fall by the destructive hand of vice. How many have been ruined by lust, slain by intemperance, or made beggars by dishonesty! But I intreat you particularly to observe, that when we set our affections inordinately upon any earthly object or enjoyment, or when they are not truly sanctified; how much they disappoint our expectation in possession, and what scenes of distress we prepare for ourselves by their removal.

Third. This request, “remove far from me vanity and lies,” implies that God would graciously preserve us from deceiving ourselves, and thinking our character better, and our state safer than it really is. When we take a view of the state of the world, and the conduct of those who have not yet cast off all belief in eternity and a judgment to come, it is impossible to account for their security, but by a great degree it is self-deceit. We may say of them with the prophet Isaiah, “He feedeth on ashes; a deceived heart hath turned him aside, that he cannot deliver his soul, nor say. Is there not a lie in my right hand?” And from the representations given by our Savior, it is plain, that many shall continue in their mistake, and only be undeceived at the last day. “Not everyone that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter the kingdom of heaven.” How awful a reflection this! How dreadful a disappointment to discover our misery, only when there is no more hope of escaping it! Is there not a possibility of this being the case with many of you, my brethren; and do you not tremble at the thought? I would not wish any, in general, to give way to a spirit of bondage, or slavish fear; but the best of the children of God have often discovered his holy jealousy of themselves. “Who can understand his errors? Cleanse thou me from secret faults. Keep back thy servant also from presumptuous sins; let them not have dominion over me, then shall I be upright, and I shall be innocent from the great transgression.” And again; ”Search me, O God, and know my heart; try me, and know my thoughts; and see if there be any wicked way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting.”

This leads me naturally to add upon this subject, that we ought to pray for preservation from self-deceit, as to particular branches of our character and conduct, as well as our general state.—Many, even upon the whole good men, are occasionally and insensibly brought, for a season, under the direction of sinful passions. They may be indulging themselves without suspicion, in what is, notwithstanding, really provoking to God, injurious or offensive to others, and in this case, hurtful to their own peace. They may be making an enjoyment a talent, a relation an idol, when they think they are keeping within the bounds of duty. They may be indulging a sinful resentment when they think they are promoting the glory of God. Many an excuse for neglecting commanded duty, from prudence or difficulty, satisfies ourselves, which will not stand in the day of trial. What reason for the prophet’s prayer in the sense just now assigned, “Remove far from me vanity and lies.”?

Fourth. In the next place, this request implies a desire to be preserved from pride and self-conceit, upon any subject. There is not anything that affords a stronger evidence of our being unacquainted with ourselves, and our own state, than that propensity to pride and vanity, which is so common to us all. It is thought by many, that pride was the sin of the angels, that cast them down to hell. It is plain, that pride was the main ingredient in the first sin of man. And perhaps it is a just, and proper description of all sin as such, that it is a dethroning of God, and setting up self to be loved, honored, and served in his place. This sin is by no means confined to the worst of men, in whom it hath an absolute dominion; but retains and discovers an unhappy influence in the very best.—Everything may be the fuel of pride: our persons our performances, our relations, our possessions; nay, so pliable, and at the same time so preposterous is this disposition, that men are found sometimes proud of their very vices and defeats. But how poorly do pride and vanity suit such poor mortals as we are, who seem born but to die?—Who after passing through a longer or shorter series of weaknesses, disappointments, and troubles, must, at last, be laid in the silent grave, to molder in the dust. We are dependent creatures, who have nothing, and can have nothing but what we receive from the unmerited favor of God. We are unwise and ignorant creatures, who know nothing fully, and therefore, are liable to continual mistakes in our conduct. Those among us, who have the greatest comprehension of mind, and know most; as it serves to show the comparative ignorance of the bulk of mankind, so it serves to convince themselves how little they do know, and how little they can know after all, compared with what is to them unsearchable.

But above all, we are sinful creatures, who have rendered ourselves, by our guilt, the just objects of divine displeasure. Is there any who dares to plead exemption from this character? And do pride and vanity become those, to whom they manifestly belong? Can anything be more foolish, than indulging such dispositions? There is a very just expression of one of the apocryphal writers: “Pride was not made for man, nor a high look for him that is born of a woman.” Indeed they are so evidently unsuitable to our state and circumstances, that one would think, we should need no higher principle than our own reason and observation to keep us free from them. We do, however, need the most earnest and assiduous addresses to the throne of grace, to have all pride and vanity removed from us.—How hateful is pride to God! We are told, he resisteth the proud.” On the contrary, no disposition is more amiable in his sight, than humility. “He giveth grace to the humble.” And again: “To this man will I look, even to him that is poor and of a contrite spirit, and trembleth at my word. For thus saith the high and lofty One, that inhabiteth eternity, whole name is holy; I dwell in the high and holy place, with him also, that is of a contrite and humble spirit; to revive the spirit of the humble, and to revive the heart of the contrite ones.”

It must, therefore, be the duty, and interest of every good man, not only to resist pride and vanity, but to make it a part of his daily supplication to God, that he may effectually be delivered from both.

Fifth. In the last place: This request implies a desire to be delivered from fraud and dissimulation of every kind. It is one of the glorious attributes of God, that he is a God of truth, who will not, and who cannot lie. He also requires of all his servants, and is delighted with truth in the inward parts. But there seems to be some difficulty in this part of the subject, more than in the others. Some will say, why pray to be delivered from fraud and dissimulation? This might be an exhortation to the sinner, but cannot be the prayer of the penitent. If they are sincere in their prayer, it seems impossible there can be any danger of fraud. Fraud implies deliberation and design; and though it may be concealed from others upon whom it is exercised, it can never be concealed from the person in whom it dwells, and by whom it is contrived. This is the very language of some reasoners, who infer from it, that though there are many other sins to which a man may be liable without knowing it, yet this can never be the case with dissimulation.

But, my brethren, if we consider how apt men are, upon a sudden temptation of fear or shame, or the prospect of some advantage to themselves, to depart from strict veracity, and even to justify to their own minds, some kinds and degrees of deceptions, we shall see the absolute necessity of making this a part of our prayer to God. Nay, perhaps I may go further and say, that we are as ready to deceive ourselves in this point as in any other.

Upon this important subject, there is one consideration to which I earnestly intreat your attention. Thorough sincerity, simplicity, and truth, upon every subject, have, in the world, so much the appearance of weakness; and on the contrary, being able to manage and over-reach others, has so much the appearance of superior wisdom, that men are very liable to temptation from this quarter. It is to be lamented that our language itself, if I may so speak, has received a criminal taint; for in common discourse the expression, a plain well-meaning man is always apprehended to imply, together with sincerity, some degree of weakness; although, indeed, it is a chamber of all others the most noble. In recommendation of this character let me observe, that in this, as in all the particulars mentioned above, “the wicked worketh a deceitful work; but he that walketh uprightly walketh surely.” Supposing a man to have the prudence and discretion not to speak without necessity; I affirm there is no end to which a good man ought to aim at, which may not be more certainly, falsely, and speedily obtained by the strictest and most inviolable sincerity, than by any acts of dissimulation whatever.

But after all, what signify any ends of present convenience, which dissimulation may pretend to answer, compared to the favor of God, which is forfeited by it? Hear what the Psalmist says. “Who shall abide in thy tabernacle, who shall dwell in thy holy hill? He that walketh uprightly and worketh righteousness, and speaketh the truth in his heart.”—Let us, therefore, add this to the other views of the prophet’s comprehensive prayer—”Remove far from me vanity and lies.”

For the improvement of this part of the subject, observe,

First. You may learn from it how to attain, not only a justness and propriety, but a readiness and fulness in the duty of prayer.

Nothing is a greater hinderance, either to the fervency of our affections, or the force of our expressions in prayer, than when the object of our desires is confused and general. But when we perceive clearly what it is that is needful to us, and how much we do need it, this gives us, indeed, the spirit of supplication. Perhaps it is more necessary to attend to this circumstance, in what we ask for our souls than for our bodies. When we want anything that relates to present convenience, it is clearly understood because it is sensibly felt.—There is no difficulty in crying for deliverance from poverty, sickness, reproach, or any other earthly suffering; nay, the difficulty here is not in exciting our desires, but in moderating them; not in producing fervor, but in promoting submission. But in what relates to our souls, because many or most temptations are agreeable to the flesh, we foresee danger less precisely, and even feel it less sensibly; therefore, a close and deliberate attention to our situation and trials, as opened in the preceding discourse, is of the utmost moment, “both to carry us to the throne of grace, and to direct our spirit when we are there.”

Second. What hath been said will serve to excite us to habitual watchfulness, and to direct our daily conversation. The same things that are the subjects of prayer, are also the objects of diligence.—Prayer and diligence are joined by our Savior, and ought never to be separated by his people.—Prayer without watchfulness is not sincere, and watchfulness without prayer will not be successful. The same views of sin and duty—of the strength and frequency of temptation, and the weakness of the tempted lead equally to both. Let me beseech you then, to walk circumspectly, not as fools, but as wise. Maintain a habitual diffidence of yourselves—Attend to the various dangers to which you are exposed. Watchfulness of itself will save you from many temptations, and will give you an inward warrant, and humble confidence, to ask of God support under, and deliverance from such as it is impossible to avoid.

Third. In the last place, since everything comprehended in the petition in the text, is viewed in the light of falsehood and deceit, suffer me, in the most earnest manner, to recommend to my hearers, and particularly to all the young persons under my care, “an invariable adherence to truth, and the most undisguised simplicity and sincerity in the “whole of their conversation and carriage.” I do not know where to begin or end in speaking of the excellency and beauty of sincerity, or the baseness of falsehood. Sincerity is amiable, honorable, and profitable. It is the most winning part of a commendable character, and the most winning apology for any miscarriage or unadvised action. There is scarcely any action in itself so bad, as what is implied in the hardened front of him who covers the truth with a lie; besides, it is always a sign of long practice in wickedness. Any man may be seduced or surprised into a fault, but none but the habitual villain can deny it with steady calmness and obstinacy. In this respect, we unhappily find some who are young offenders, but old sinners.

It is not in religion only, but even among worldly men, that lying is counted the utmost pitch of baseness; and to be called a liar the most insupportable reproach. No wonder, indeed, for it is the very essence of cowardice to dare to do a thing which you have not courage to avow. The very worst of sinners are sensible of it themselves, for they deeply resent the imputation of it; and, if I do not mistake, have never yet arrived at the absurdity of defending it. There is scarcely any other crime, but some are profligate enough to boast of it; but I do not remember ever to have heard of any who made his boast, that he was a liar. To crown all, lying is the most wretched folly. Justly does Solomon say: “A lying tongue is but for a moment.” It is easily discovered. Truth is a firm confident thing, every part of which agrees with, and strongly supports another. But lies are not only repugnant to truth, but repugnant to each other; and commonly the means, like a treacherous thief, of the detection of the whole. Let me, therefore, once more recommend to every one of you, the noble character of sincerity.—Endeavor to establish your credit in this respect so entirely that every word you speak may be beyond the imputation of deceit; so that enemies may, themselves, be sensible, that though you should abuse them, you will never deceive them.