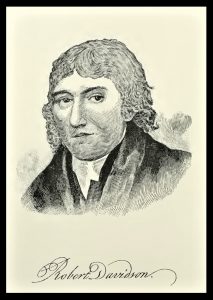

Robert Davidson was born near the Elk River in Elkton, Maryland, in 1750. His early education prepared him for the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) where he graduated 1771 during the administrative tenure of Francis Alison (Old Side Presbyterian). The next year Davidson was licensed to preach and appointed an instructor in the college until he was selected professor of history. John Ewing, the pastor of First Presbyterian Church and a faculty colleague, became a close friend. Ewing needed help shepherding the flock at First Church leading to Davidson’s ordination by the Second Presbytery of Philadelphia to become his assistant. Ewing saw in Davidson a man of many interests and successfully sponsored him for membership in 1783 in the American Philosophical Society. Davidson was a capable scholar with facility in eight languages and established within the city and Pennsylvania a reputation for his gifts and leadership.

Robert Davidson was born near the Elk River in Elkton, Maryland, in 1750. His early education prepared him for the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) where he graduated 1771 during the administrative tenure of Francis Alison (Old Side Presbyterian). The next year Davidson was licensed to preach and appointed an instructor in the college until he was selected professor of history. John Ewing, the pastor of First Presbyterian Church and a faculty colleague, became a close friend. Ewing needed help shepherding the flock at First Church leading to Davidson’s ordination by the Second Presbytery of Philadelphia to become his assistant. Ewing saw in Davidson a man of many interests and successfully sponsored him for membership in 1783 in the American Philosophical Society. Davidson was a capable scholar with facility in eight languages and established within the city and Pennsylvania a reputation for his gifts and leadership.

To the west of Philadelphia, Dickinson College was getting underway and the trustees were searching for personnel to teach and lead the new institution. Dickinson had just been chartered through the persistent work of Benjamin Rush, 1783, who was inspired by the success achieved by the trustees of Princeton College with their selection of John Witherspoon as president. Rush believed a college in the western part of the state was of paramount importance as pioneers settled the frontier. Dickinson is named for founding father and “penman of the Revolution,” John Dickinson, and it was the first college established in the United States. The candidate filling the available faculty position would need a breadth of knowledge to become professor of history, geography, chronology, rhetoric, and belles lettres, to which later natural science would be added. Ewing thought his pastoral colleague was a good candidate and after some encouragement, Davidson accepted the appointment. He left Philadelphia for Carlisle in 1784, but not before the College of Pennsylvania trustees showed their appreciation for his thirteen years of work by honoring him with the Doctor of Divinity.

Davidson’s move to Carlisle soon provided an opportunity to continue the professor-pastor calling he had in Philadelphia. The First Presbyterian Church needed a minister desperately because its previous minister, John Steel, had passed away more than five years earlier and a suitable candidate could not be located. Contributing to the pastoral search problems was division within the congregation. When Steel passed away in 1779, First Church, because of a stipulation resulting from the Old Side-New Side division of the Presbyterian Church (divided 1741-1758) had to change its presbytery membership from Second Presbytery of Philadelphia (Old Side during the division) to the Presbytery of Donegal (New Side during the division). First Church had met in two meeting houses with the Old Side pastored by Steel and the New Side by George Duffield. At one point during the division, the two groups shared the courthouse with each group meeting at different times on the Lord’s Day. Since reunion, the congregation worshipped in a single gathering, but its lack of singlemindedness was hampering the search for a pastor.

Davidson’s move to Carlisle provided First Church with a candidate the congregation could accept. Dickinson College and First Church would enjoy a close relationship because faculty and students would attend and work in the church. Carlisle was a decidedly Presbyterian town as Conway P. Wing observed commenting that the village was “the strongest and most compact body of Presbyterians in America … then and was likely to be for some time in this region” (119). Carlisle was both a settlement for Presbyterians and geographically where their migration route began its turn south to distribute Calvinist settlers along the Shenandoah frontier into Virginia, eastern Tennessee, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Davidson was offered and accepted a pastoral call, but first his presbytery membership had to be transferred to the Presbytery of Donegal as recorded in the minutes, April 12, 1785.

The Rev. Dr. Davidson, having accepted a call from the First Church of Carlisle and now having settled in that place, produced a certificate of his dismission from the Second Presbytery of Philadelphia and applied to be received as a member. He is accordingly received and takes his seat.

John Montgomery, an elder from First Church, asked the moderator to appoint a committee for installation of Davidson; Robert Laing and Samuel Waugh were assigned to lead the special service, Wednesday, April 27. Davidson was set to fulfill his callings in Carlisle with lectern at one hand and the pulpit the other.

But there was another factor in addition to the remnants of division at First Church affecting Davidson’s work and it was associated with Dickinson College.

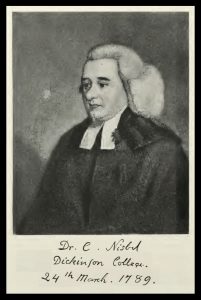

In July, 1785, Charles Nisbet would arrive from Scotland to become the first principal (president) of Dickinson College. But before Nisbet began his duties in the fall, he and his family were stricken with illness. He thought the Carlisle climate was too challenging for his constitution, so he resigned to return to bonnie Scotland. Dickinson needed a leader, so Davidson performed the necessary duties of principal in addition to his already heavy preaching-teaching load. When the Nisbets recovered, Charles decided he wanted to keep the Dickinson principalship, so he was rehired. The potential problem for Davidson at First Church was Nisbet would share the pulpit with him half time for both morning and evening services, but Davidson would do all the pastoral work. Added to this was a promise by the church to George Duffield that he could preach on occasion. Neither Nisbet nor Davidson was known for oratorical magnificence, so maybe the arrangement worked out well because their pulpit skills were unlikely to seed factions.

In July, 1785, Charles Nisbet would arrive from Scotland to become the first principal (president) of Dickinson College. But before Nisbet began his duties in the fall, he and his family were stricken with illness. He thought the Carlisle climate was too challenging for his constitution, so he resigned to return to bonnie Scotland. Dickinson needed a leader, so Davidson performed the necessary duties of principal in addition to his already heavy preaching-teaching load. When the Nisbets recovered, Charles decided he wanted to keep the Dickinson principalship, so he was rehired. The potential problem for Davidson at First Church was Nisbet would share the pulpit with him half time for both morning and evening services, but Davidson would do all the pastoral work. Added to this was a promise by the church to George Duffield that he could preach on occasion. Neither Nisbet nor Davidson was known for oratorical magnificence, so maybe the arrangement worked out well because their pulpit skills were unlikely to seed factions.

It appears that the church, Nisbet, and Davidson got along well and the two ministers were able to effectively share worship leadership. However, when the Whiskey Rebellion over taxation of spirits took place in 1794 in the western part of the state, Davidson, one Sunday morning temperately spoke of the duty the people had to express their views in constitutional ways while submitting to the powers that be; it was not a popular sermon for some in the congregation, but not too many feathers were ruffled. Then when Nisbet preached on the same subject using 1 Thessalonians 4:11 for his text, he more bluntly spoke of the people’s duty to mind their own business and work with their hands in their occupations, and leave the law making to the government—the sermon did not go over well as indicated by feathers flying with some congregants complaining that Nisbet echoed the tyranny of George III and reasons for the Revolution. But despite different methods in their sermons, they both agreed the people needed to obey the law.

When Nisbet died in 1804, Davidson delivered the memorial sermon and became the president of Dickinson pro-tem and continued until the next president was located. Davidson turned down the presidency as did Samuel Miller, but a new principal was found in Vermont when the president of Middlebury College, Jeremiah Atwater, was selected. The new administration was Davidson’s opportunity to resign from all teaching and other responsibilities at the college.

Davidson’s preaching displayed his breadth of interests because he often used scientific and historical illustrations as he read manuscript sermons that never, ever, exceeded an hour, even if he had to stop midsentence (this is according to his son who was four when his father died). Davidson had a presence and bearing in the pulpit, fostered respect among the people, and congenially shepherded the flock. The children were a particular joy to him. He and his first wife were unable to have children and he did not become a father until nearly sixty years old when his second wife delivered a son they named Robert Davidson. The congregation’s children had become his own for many years. As was the norm in the day for Presbyterians influenced by Scottish practices, he catechized the children according to age groups weekly.

He was a good minister but science increasingly drew his attention. Astronomy fascinated him and some of his research led to publication of scientific papers and fabrication of an apparatus called a compound globe which he named a cosmosphere. It was some type of three-dimensional model of the solar system or the universe.

Davidson participated in the Presbyterian judicatories at all levels including moderator of the Synod of Philadelphia, 1795, and then in 1796, the poorly attended and brief for the day (less than five days of sessions) General Assembly that met in in Philadelphia. Issues that came before him dealt with: the inability of the Synod of Philadelphia to obtain a quorum in 1795; continuing to improve relations with the General Association of Connecticut (Congregational); the publication of a new edition of the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church; a controversial overture that was tabled which had attempted to have a Presbyterian hymnal compiled from existing ones; and discussion of a change to the Form of Government that would facilitate the assembly meeting every three years by having synods take up more of the load. When he returned to Philadelphia the next year his moderator’s sermon was delivered from Psalm 72:17, “His name shall endure forever; his name shall be continued as long as the sun; and men shall be blessed in him; all nations shall call him blessed.”

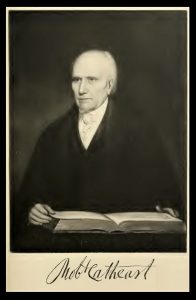

Robert Davidson, D.D., died on the Sabbath, December 13, 1812, of “dropsy in the chest, after protracted agonies.” Dropsy described the accumulation of fluid in any part of the body. His memorial sermon was preached by his friend and ministry colleague, Robert Cathcart, and was published bearing the title, A Sermon on the Death of the Rev. Robert Davidson, D.D., who died December 13th, 1812: Preached in the Presbyterian Church in Carlisle, February 28th, 1813, in Carlisle in 1813. The delay in the memorial service may be indicative of a cold Pennsylvania winter and hard ground. He is buried in what is currently called the Old Graveyard in Carlisle where he is remembered on a recently installed bronze plaque as a patriot with other men who contributed to the American Revolution. On his grave marker he is remembered as “A Blessed Peacemaker.”

Robert Davidson, D.D., died on the Sabbath, December 13, 1812, of “dropsy in the chest, after protracted agonies.” Dropsy described the accumulation of fluid in any part of the body. His memorial sermon was preached by his friend and ministry colleague, Robert Cathcart, and was published bearing the title, A Sermon on the Death of the Rev. Robert Davidson, D.D., who died December 13th, 1812: Preached in the Presbyterian Church in Carlisle, February 28th, 1813, in Carlisle in 1813. The delay in the memorial service may be indicative of a cold Pennsylvania winter and hard ground. He is buried in what is currently called the Old Graveyard in Carlisle where he is remembered on a recently installed bronze plaque as a patriot with other men who contributed to the American Revolution. On his grave marker he is remembered as “A Blessed Peacemaker.”

Davidson’s written works include in 1811, Psalm 119 in meter bearing the title, The Christian’s A. B. C.s, and the next year was published, A New Metrical Version of the Whole Book of Psalms; in Various Measures, More Free, Plain and Harmonious, and More in the Language of the New Testament, than Former Translations, with Occasional Notes and Illustrations, Carlisle: Printed by Alexander & Phillips. He also issued a geography book titled, Geography Epitomized, or A Tour Round the World: Being a Short but Comprehensive Description of the Terraqueous Globe, Attempted in Verse, for the Sake of Memory, and Principally Designed for the Use of Schools, 1784, which was reprinted several times to at least 1812. His memorial sermon for George Washington was published but a copy proved elusive; Davidson had preached to General Washington and his troops at the Carlisle Barracks during the Whiskey Rebellion.

He left twenty volumes of manuscript sermons and scientific lectures which are partially or fully held by Dickinson College Special Collections (very informative website). During his twenty-seven-year ministry in First Church, 498 individuals were admitted to the church with 330 of them added on profession of faith. According to his own notation, the membership in 1812 was over two hundred. Robert was survived by his like-named son, and his third wife, Jane (Harris) Davidson. He was first married to Abigail for over thirty years until she was killed when her carriage overturned in 1806, and his second wife was Margaret Montgomery who passed away in 1809 after a brief marriage.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header is a view of University of Pennsylvania buildings. It looks mid-nineteenth century from the New York Public Library digital collection.

Some information about Robert Davidson and Dickinson College in particular was located in Charles Coleman Sellers, Dickinson College: A History, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1973; and Horatio C. King’s, History of Dickinson College, New York: The American University Magazine Publishing Company, 1897.

Four biographies of Davidson were accessed. The first was written by his son Robert, and it is in William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 3, Presbyterians, 1858, pages 322-26; the second is available in Alfred Nevin’s Centennial Biography: Men of Mark of the Cumberland Valley, PA. 1776-1876, 1876, pages 112-13; the third life was written by Conway P. Wing in A History of the First Presbyterian Church of Carlisle, PA., 1877, pages 116-48; and the fourth is included among a number of biographies in The Centennial Memorial of the Presbytery of Carlisle, vol. 1-Historical, vol. 2-Biographical, 1889; vol. 1 provided Davidson’s and Nisbet’s portraits and vol. 2 provided Cathcart’s. Davidson’s son’s biography in Sprague is revised in Nevin’s Centennial to provide a more generous perspective on dad; the version in the Presbytery of Carlisle volume made use of Sprague and Nevin, but the best source for a substantial part of Davidson’s life during the Carlisle years is Wing’s bit about him in the First Church history. Another helpful title is by Allan D. Thompson, The Meeting House on the Square, Carlisle, 1964, which is a history of First Church. Samuel Miller wrote, Memoir of the Rev. Charles Nisbet, Late President of Dickinson College, Carlisle, New York: Robert Carter, 1840.

See the post, “The Tennent Family and William Mackay Tennent,” regarding the common use of the same given name for the descendants in a family and the need for care when reading sources.