Thomas Verner was born February 1, 1818 to John and Rachel (McCullough) Moore in Newville, Pennsylvania. His father had emigrated from Ireland and was a middling-sort operator of a local water-driven mill. Thomas’s last few years of preparatory studies were directed by his pastor, Robert McCachren of the Big Spring Church, and included among his school books was an 1834 copy of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church. Formal education for Moore began with a year at Hanover College in Indiana. During studies there he met Sarah, the daughter of the first president of Hanover, James Blythe. Sarah and Thomas would marry in 1842. Moore transferred to Dickinson College to be near his family. Graduating in 1838 he went east to study theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. Among his classmates was John Miller the son of Professor Samuel Miller. Moore was particularly fond of Oriental and Biblical Literature Professor J. A. Alexander and they enjoyed a life-long friendship. Following completion of studies in 1842, he became an agent for the American Colonization Society in Pennsylvania. Colonization was a movement to purchase freedom for enslaved people then transport them to Africa to live in their own colony. Archibald Alexander was sympathetic to colonization, so his teaching at Princeton Seminary could have contributed to Moore’s interest in the movement. The current nation of Liberia came from the colony that was established. Moore became discouraged about colonization because the amount of money needed to accomplish manumission and relocation of just one person was great and the financial resources required to move multitudes of individuals was inconceivable. Looking at the movement today, it is hard to believe the proponents of colonization really believed the program would work, likewise, Moore’s disenchantment could have developed as he realized the plan was not feasible.

Thomas Verner was born February 1, 1818 to John and Rachel (McCullough) Moore in Newville, Pennsylvania. His father had emigrated from Ireland and was a middling-sort operator of a local water-driven mill. Thomas’s last few years of preparatory studies were directed by his pastor, Robert McCachren of the Big Spring Church, and included among his school books was an 1834 copy of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church. Formal education for Moore began with a year at Hanover College in Indiana. During studies there he met Sarah, the daughter of the first president of Hanover, James Blythe. Sarah and Thomas would marry in 1842. Moore transferred to Dickinson College to be near his family. Graduating in 1838 he went east to study theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. Among his classmates was John Miller the son of Professor Samuel Miller. Moore was particularly fond of Oriental and Biblical Literature Professor J. A. Alexander and they enjoyed a life-long friendship. Following completion of studies in 1842, he became an agent for the American Colonization Society in Pennsylvania. Colonization was a movement to purchase freedom for enslaved people then transport them to Africa to live in their own colony. Archibald Alexander was sympathetic to colonization, so his teaching at Princeton Seminary could have contributed to Moore’s interest in the movement. The current nation of Liberia came from the colony that was established. Moore became discouraged about colonization because the amount of money needed to accomplish manumission and relocation of just one person was great and the financial resources required to move multitudes of individuals was inconceivable. Looking at the movement today, it is hard to believe the proponents of colonization really believed the program would work, likewise, Moore’s disenchantment could have developed as he realized the plan was not feasible.

Moore resigned from the colonization work and accepted a call to Second Presbyterian Church, Carlisle. Second Church was a result of division because it was founded when the Old School-New School schism of 1837 occurred. One resident of Carlisle commented the situation was so bad in town that members of First and Second Churches would pass each other on the way to their respective churches and not speak to each other. Moore was attending Dickinson when debates about the division occurred, so he knew something about the situation he was taking on for his first call. He succeeded Alexander T. McGill who left Second Church after a short and trying tenure. After a difficult four-year call, Moore thought about demitting the ministry but because of encouragement from presbytery and friends he continued to pastor. Putting the Carlisle experience behind him, he moved to the church in nearby Greencastle but stayed only a few years before he candidated at First Church, Richmond, Virginia. Pastor William S. Plumer had left Richmond after ten years of ministry to lead the Franklin Street Church in Baltimore. Candidates considered for the Richmond call before Moore included Stuart Robinson, B. M. Smith, and at least four others. Moore accepted the call and packed the family possessions to move to Richmond in 1847.

Richmond was different from the strongly Scotch-Irish Presbyterian community surrounding Carlisle. Ecclesiastically, the Virginia capital was becoming more Presbyterian but the Church of England presence from colonial days continued with a strong Episcopal presence while Baptists and Methodists increased in number. First Church was founded in 1812 under the ministry of John H. Rice who would also bring stability for nearby struggling Union Seminary. Richmond was a hub for railroads and boat traffic on the James River, and its warehouses were filled with tobacco. The Moores appreciated the milder weather of their new home, other aspects would become accepted, but comments in their correspondence show there were aspects of Richmond life they could not understand. Sarah was befuddled when she went to a tea held by the wife of an elder in a home that was ostentatious and just not what the Carlisle girl was used to.

Sarah and Mr. Moore, as she called her husband, soon had their fourth child, Francis Dean (Frank) in 1849. But as was common in the day, complications from delivery of the infant caused Sarah’s death just a few days later. Soon, Moore made the acquaintance of Matilda Gwathmey, the daughter of a First Church elder. The two were married by William S. Plumer while attending the Old School General Assembly convened in Charleston, South Carolina in 1852. Thomas and Matilda would have two children.

Moore continued to serve First Church for several more years. Before the Civil War he was a prolific writer with much of his work published in journals, newspapers, and pamphlets. He joined Moses D. Hoge, the minister of Second Church, to purchase and publish The Central Presbyterian with editorials and articles by both men. After Virginia seceded from the Union, Richmond was the capital of the Confederacy as well as its logistical and tactical hub for much of the war. As the conflict continued the Moores suffered through food shortages, increased crime, deprivations caused by the Union blockade, bread riots, tax riots, currency riots, hospitals overflowing with Union and Confederate wounded, reoccurring fires in the city, and economic inflation. The city included several prisons for Federal captives and hospitals for troops from both sections. Because of his Pennsylvania and Princeton connections, Moore received letters from friends of the past seeking help for their imprisoned loved ones so they could return home. For example, fellow Princetonian John Miller asked for help for a wounded friend, and a family in Carlisle sought assistance for two of its sons. He spent hours every week visiting the wounded of both armies in the Richmond hospitals and prisons. It was physically exhausting for Moore. Comparing portraits of him when he arrived in Richmond and then when he left shows a dramatic change from a dapper young minister with an optimistic glint in his eye to an overweight, sad eyed, and worn-out old man of fifty struggling with a debilitating disease. It is unclear what the disease was, but it appears to have been tuberculosis contracted, possibly, while visiting prisoners and the sick in hospitals. Added to his challenges were some within his congregation chastising him for ministering to Federal soldiers. The sick and imprisoned troops were in Richmond for political reasons, but politics did not negate their spiritual needs.

The doctrine of the spirituality of the church is sometimes criticized because it was used by some Presbyterians during the antebellum nineteenth century to defend the American practice of slavery. Doctrine is essential, immutable truth, and the way it is used or misused neither validates (in the sense of proving it is true) nor denies its veracity. John Calvin’s distinction between the ministries of the church and state provides a foundation for the nineteenth-century American doctrine of the spirituality of the church. As Calvin studied the Bible he concluded, the state brings fear to those who transgress the law and make it unsafe for Christians to dwell in peace and worship God; the state bears the sword, and it does so as a minister of God and should do so consistent with Scripture; the state’s work is physical, tangible, visible, and sometimes necessarily involves force. The church’s spiritual work with the keys to the kingdom through the ministry of the Word brings individuals to faith and directs worship as they grow in sanctification; the church’s work is invisible but yields visible results in the lives of its members. Thus, the line between what the church does and what the state does is clear. Moore exemplified the spirituality of the church in his pastoral work. For him, the war was a conflict between political entities bearing the sword, but his residence in Richmond and commitments to the Confederacy did not stop him from fulfilling his calling by visiting soldiers from both sides in the hospitals and prisons of Richmond. One might think that any minister entering a hospital and seeing an enemy soldier suffering at the door of eternity would give spiritual counsel and the words of life. But tragically, this was not the case because some ministers and chaplains on both sides passed by enemy soldiers in need, even in some cases berated them, but there were others like Moore who exemplified the spiritual nature of the church’s work in the midst of a political war. Moore was sympathetic to the South because of his commitment to republicanism and his belief that a confederation of republican states was the best government for the nation, but it is unclear, as indicated by his colonization work, what his view of slavery was.

In 1867, Moore was elected moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) when it convened in First Church, Nashville, Tennessee. The retiring moderator, Andrew H. Kerr, opened the sessions delivering his sermon from Psalm 48:1, 14. Among the business items to pass before Moore were an overture from the Presbytery of Patapsco of the PCUSA seeking union with the PCUS, which on motion by Joseph R. Wilson was adopted. A delegation from the Old School Synod of Kentucky (PCUSA) that included Stuart Robinson arrived during the sessions and after considerable work in committee and floor debate it was resolved to have the Synod of Kentucky unite with the PCUS; and the Synod of Missouri came before the assembly about issues with the PCUSA. William S. Plumer was installed a professor in Columbia Theological Seminary during a service one evening after having been appointed to the chair by the previous General Assembly. One action indicative of the continued difficult economic situation of the region was adoption of an overture from the Synod of South Carolina calling for a day of fasting and prayer January 24, 1868 “in view of the extraordinary distress of God’s people in this land, to observe said day by suitable religious exercises.” An interesting action noted in the minutes involved Benjamin Gildersleeve, et al, who proposed that the Southern Presbyterian Review be recommended by the General Assembly to the churches, however, it was resolved instead, “That while this Assembly, as ministers and elders, might cordially adopt the paper presented, yet, as an Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in its ecclesiastical character, it is not competent for us to enact anything concerning other matters than those which are strictly ecclesiastical.” A curious response regarding a publication with “Presbyterian” in its title. Was the Assembly saying there was too much politics or other subjects not germane to the work of the church for the publication to be recommended? One issue the PCUS struggled with for years was coming up with a book of church order acceptable to all, and the subject came to the floor before Moore. It was reported that the presbyteries had reported their opinions about the revised BCO and they were dissatisfied considerably. Added to this sample of some of the numerous items processed in 1867 was the continued question of how to deal with the end of slavery, the Assembly addressed particularly separate theological training for black ministerial candidates. The sessions extended from November 21 to 29, with much accomplished, but Moderator Moore must have found it trying given the limitations of his health.

One benefit of Moore’s sojourn in Nashville moderating the General Assembly was that in 1869 he was given a call to pastor First Church, which he accepted. The four years since the war ended had not been peaceful in First Church, Richmond, with some members continuing to challenge his ministry because of his work in the hospitals and prisons during the war. Also, the milder weather that Moore had enjoyed so much when he moved to Richmond from Pennsylvania had become too harsh for him, so the move to Nashville was hoped to provide a milder climate. After just two years ministry with a good portion of the time spent in Florida due to his health, T. V. Moore died August 5, 1871. He was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery following a funeral conducted by a committee of Nashville’s ministers including a good friend from Princeton days, John H. Rice. Despite instructions to his survivors to purchase a simple and small marker with a brief inscription, an obelisk roughly twelve feet high marks the grave.

A close friend of Dr. Moore was Thomas Ward White, who was president of Reidville Female College in South Carolina. White had known Moore from their work as presbyters in East Hanover Presbytery in Virginia. In a paragraph from White’s lengthy obituary he provided a picture of Moore’s study habits.

Dr. Moore was a most laborious student. Feeling that genius without incessant application would avail but little, he gave himself wholly to his studies. He was one of the most rigid economists of time we have ever seen, possessing at the same time the rare capacity of keeping his mind closely fixed on the subject before him, regardless of the numberless and nameless interruptions incident to a pastorate in a large city. We have seen him answer the doorbell, return, and finish a sentence without the slightest interruption. Writing very rapidly, we have been told that at the time of his removal to Nashville, he had on hand not less than a thousand carefully prepared manuscript sermons, written out in full. He always retired and rose early. His freshest and best hours were invariably given to God. He was seldom seen at home or abroad without a book in his hand.

A result of T. V. Moore’s disciplined work is numerous sermons and lectures as well as articles, but his most substantial publications are The Culdee Church: or, The Historical Connection of Modern Presbyterian Churches with those of Apostolic Times, Through the Church of Scotland, 1868, which is a reprint of a series of articles he ran in The Central Presbyterian, and two books that have been reprinted by Banner of Truth—his commentary on the books of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, and his series of sermons published in The Last Days of Jesus: The Forty Days Between the Resurrection and the Ascension, 1858. Published in issues of The Confessional Presbyterian are articles about Moore including: “Review: T. V. Moore, The Last Days of Jesus,” by C. N. Willborn (No. 7, 2011); by the author of this site are, “An Introduction to T. V. Moore through his Essay on Juvenile Delinquency,” (No. 7, 2011), “In Brief: T. V. Moore’s Twenty Hints for a Happy Family,” (No. 7, 2011), and a reprint of Moore’s article, “The Lord’s Day, the Christian Sabbath,” (No. 12, 2016). He was given the Doctor of Divinity by Dickinson College in 1853. For a sample of Moore’s verse, see the post “T. V. Moore’s Poetry.”

Barry Waugh

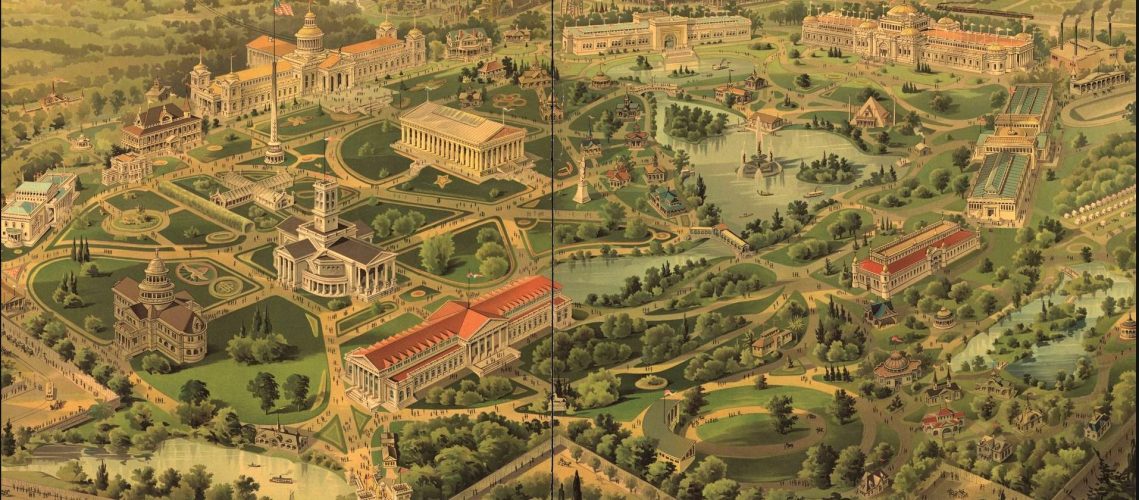

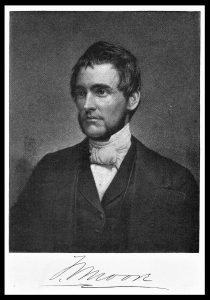

Please note that there are two different men named John H. Rice in this biography. The header is snipped from an aerial view image of the 1897 Tennessee Centennial as held by the Library of Congress in its digital collection; the columned building in the center of the image is an extant replica of the Parthenon in Athens with a statue of Athena. The portrait of Moore dates to his days in Carlisle Presbytery and is from the two-volume history of Carlisle Presbytery.