In 1800, Philadelphia was the seat of the U. S. Government, but that was about to change. On May 15, President John Adams sent a brief letter to federal department heads instructing them to commence relocation of their offices from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia with the goal for completion June 15. After a decade as the national capital, the government was moving from the city on the Delaware River to the diamond-shaped district designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant on the Potomac. While Adams’s letter was being circulated, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) convened in First Church just a few blocks from Adam’s presidential residence. The center of the national government was shifting, but the Presbyterians had no intention of relocating its hub of government because for the next thirty-four years assemblies would gather in one of the Philadelphia churches. The meeting in 1800 was called to order by the alliteratively and majestically named Samuel Stanhope Smith who delivered his retiring moderator’s sermon from Jude 3—“Beloved, when I gave all diligence to write unto you of the common salvation, it was needful for me to write unto you, and exhort you, that ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints.” Smith was likely the best-known Presbyterian in the nation not only because he was president of the College of New Jersey (Princeton) having succeeded his father-in-law, John Witherspoon, but also because of his pastor-educator father, Robert, and his minister brothers, John Blair and William Richmond. The Smiths were a divinity dynasty. Even though he was an alumnus of the College of New Jersey, Smith’s successor as moderator was more simply named Joseph Clark, who had been a tradesman working in carpentry before entering the ministry.

Joseph Clark was born near Elizabethtown, New Jersey, October 21, 1751, to parents whose names are lost to history. Information about his early years is limited to his membership in the Elizabethtown Church. At the age of seventeen he was taken on by a carpenter to apprentice and Clark continued in the trade for more than three years before becoming convinced he was called to the ministry. Carpentry was a good trade but not one that often yielded wealth, so obtaining an education would be a challenge for him, but his experience working wood might prove beneficial in ministry as he served The Carpenter and the Cross. Added to money troubles was the American Revolution interrupting his studies at the College of New Jersey. He joined the Revolution in 1776 serving in the New Jersey militia and other units including one that wintered at Valley Forge with General Washington. He continued in the war effort until he left the army late in 1779 to return to Princeton, complete studies, and graduate at the age of twenty nine with five classmates in 1781. As was the practice in the day, personal instruction in theology was provided by ministers and John Woodhull had mentored many ministers before adding Clark to his catalog of graduates. With the surrender of the British at Yorktown, Woodhull reopened his classical school with Clark the teacher. Woodhull promoted his school saying, “Mr. Clark, a very worthy and capable gentleman, late of New-Jersey College, is instructor, who gives the fullest satisfaction, so that the school is already in a flourishing state” (Craven, 319). Clark was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of New Brunswick, April 23, 1783, and after supplying different pulpits, he was appointed stated supply of the church in Allentown, New Jersey, for a term of six months. On June 15, 1784 he was ordained by his presbytery sine titulo (without call). He continued supplying the Allentown church and was offered three calls by the congregation before he acquiesced with the fourth leading to installation on June 12, 1788. The installation attendees enjoyed both a sermon and pastoral charge from John Witherspoon, who was joined for the installation by John Woodhull, Mr. Thomas Smith, Mr. Armstrong, and Mr. Monteith. F. Dean Storms’s account of Clark’s years with the church presents an apparently challenging tenure which may be indicative of why he was reluctant to accept a call in the first place. When it came time for Clark’s resignation to accept a call to the New Brunswick Church, Allentown would not let him go and fought the dismissal in presbytery. Once dismissal was achieved, he moved to the church in New Brunswick and continued ministry until his death, apparently from a stroke, October 19, 1813. His working life began with wood and blades and ended after years of faithful ministry locally and connectionally for his Lord, the carpenter.

Even though Joseph Clark might not qualify for the top ten list of Presbyterians of his era in terms of prominence, he was nevertheless a devoted worker, and it is sometimes the case that those in the background are the most efficient. In the last few years of the eighteenth century the churches in the western frontier—for example, the current states of Kentucky, West Virginia, Alabama, and Tennessee—were struggling and their plight came before the General Assembly. Pastor Clark was appointed along with two other men to raise funds for western missions. He was able to collect the substantial amount of nearly 7000.00. Inter-church relations entered the Assembly’s work when it approved a program for improving ties with other denominations. Clark was appointed to a committee that met with the Associate Synod, Associate Reformed Synod, and Reformed Dutch Church concerning areas of cooperation. However, the effort proved unsuccessful despite the committee’s best efforts.

The College of New Jersey was important to Joseph Clark. As a member of the class of 1781 he went on to receive the A.M. in 1784 and then showed his continued interest in the college by becoming a trustee in 1800 and serving till his death. In March, 1802, Nassau Hall was destroyed by fire. Nassau had survived occupation by the British Army bearing the artifact of a cannonball in its wall only to be burned by a fire that started in the belfry. President Smith attributed it to irreligious students committing arson, but this seems unlikely since the students were gathered for dinner within and such an act could have been suicidal. It was more likely a student sneaking a pre-dinner puff on a pipe or draw from a residence room rolled cigar. Clark became a collector of funds to repair the extensive loss. He travelled into Virginia and collected considerable funds thanks in part to his colleague who was well acquainted with plantation owners in Virginia. When Princeton Seminary opened in 1812, Clark was appointed a director but his death the next year made for a short tenure.

Returning to the General Assembly of 1800, Moderator Clark led the presbyters for nine days of sessions excluding Sabbaths with the assembly ending May 26. The two clerks elected for the meetings were Drury Lacy and Nathaniel Irwin. The bills and overtures committee appointed was told to convene at six the following morning, which is indicative of the communications received and busy deliberations ahead. Items before the judicatory included Psalmody with the subject of Timothy Dwight’s version of the Psalms central and one man’s letter regarding Psalmody referred to a committee for recommendations; revision of the Form of Government 11:6 concerning how the power of the General Assembly was to be limited by the presbyteries; and one of the most persistent problems faced by the Presbyterians since the earliest days of Colonial America, the transfer of ministers from foreign countries, primarily Great Britain. Indicative of the minister transfer problem was a Mr. Steele whose credentials had been found deficient by the Synod of Virginia as he sought transfer from Ireland’s Presbytery of Londonderry. In some cases, ministers were accepted only to find out later they had been disciplined by their home presbyteries, or were of proven poor moral character at home. Also, Enlightenment thought was more prominent in education in Europe and foreign ministers needed to be admitted with care through thorough examination. Communication in 1800 was slow because letters were transported by travelers on slow-moving ships to the addressees. The issue was handed to a special committee leading to adoption of a lengthy statement after extended debate and recommittal to the committee. The two-page text of the statement required foreign ministers to apply to the appropriate presbytery and not preach until they were examined by the presbytery. A simple certificate of good standing needed to be buttressed by private letters or other documents “as shall fully satisfy them [presbytery] as to the authenticity and sufficiency of his testimonials” (p. 200). Presbytery should then examine the man through simple conversation followed by thorough examination in all subjects. If found suitable, he was then received on probation whether a candidate or minister. Other aspects are included in the processing, but the standard required presbyteries to exercise great care and not fear extending the probationary period. One interesting issue that arose involved South Carolina Presbyterianism. A gathering of presbyters calling itself “The Presbytery of Charleston in South Carolina,” had a letter seeking admission to the General Assembly delivered by Ashbel Green. This presbytery had been an independent judicatory for about ten years and was seeking to establish a connectional relationship. Moderator Clark appointed a committee of six which included among its members John Rodgers, and Alexander McWhorter. The Low Country presbyters had already attempted to unite with the Synod of the Carolinas but were not admitted. The committee’s report was adopted.

After examining the papers and propositions brought forward by the Charleston Presbytery, the committee thinks it expedient that the General Assembly refer this business to the consideration of the Synod of the Carolinas, with whom this Presbytery must be connected, if they become a constituent part of our body. That the said Synod be informed that the Presbytery ought, in the event of a connection with us, to be allowed to enjoy and manage, without hindrance or control, all funds and moneys that are now in their possession; and that the congregations under the care of the Presbytery be permitted freely to use the system of psalmody which they have already adopted. That, on the other hand, the Synod must be careful to ascertain that all the ministers and congregations belonging to the Presbytery do fully adopt, not only the doctrine, but the form of government and discipline of our Church. That the Synod of the Carolinas, under the guidance of these general principles, should be directed, if agreeable to them and to the Presbytery, to receive said Presbytery as a part of that Synod. But if the Synod or the Presbytery find difficulties in finally deciding on this subject, that they may refer such difficulties and transmit all the information they may collect relative to this business, to the next General Assembly (189).

The issues involved money, psalmody, and some question regarding the ability of the Charleston presbyters to fully adopt the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church. The constitutional issue may be concerned with the polity situation in the Low Country addressed in “Aaron W. Leland, Congregationalism and Grassroots Presbyterianism,” but given the impending Plan of Union between New England Congregationalists and the PCUSA in 1801 which was followed by the General Assembly of 1802 (moderated by Azel Roe) encouraging churches to use Dwight’s version of Watts’s Psalms, it really does not seem polity was the issue. The General Assembly was adjourned to meet once again in Philadelphia in First Church, when Joseph Clark would preach his sermon from Matthew 28:18-20 and then yield the podium to the new moderator, Nathaniel Irwin.

Joseph married Margaret the daughter of Peter Imlay of Monmouth County sometime after he graduated college and was studying with Woodhull. The couple, according to Sprague, had one daughter and three sons. Storms notes that a twelve-year-old son, Robert, and infant named Mary died in 1794, possibly from an epidemic. The Clarks’ eldest son, John Flavel Clark, attended Princeton and became a minister after attending Andover Theological Seminary. John was a director at Princeton Seminary, 1831-1834. Joseph Clark’s publications were few: Rules Established by the Presbytery of New Brunswick, 1800, (signed by Moderator Joseph Clark, but a document adopted by the presbytery); A Sermon on the Death of the Hon. William Patterson, 1806; Sermon Delivered in the City of New Brunswick…July 30, 1812, Being the Day Set Aside by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church for Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer¸ 1812; and “The True and False Grounds of Religion,” sermons 14 and 15 in G. S. Woodhull and I. V. Brown, editors, The New Jersey Preacher, 1813. In 1809, he was honored with the degree of Doctor of Divinity from Jefferson College.

Barry Waugh

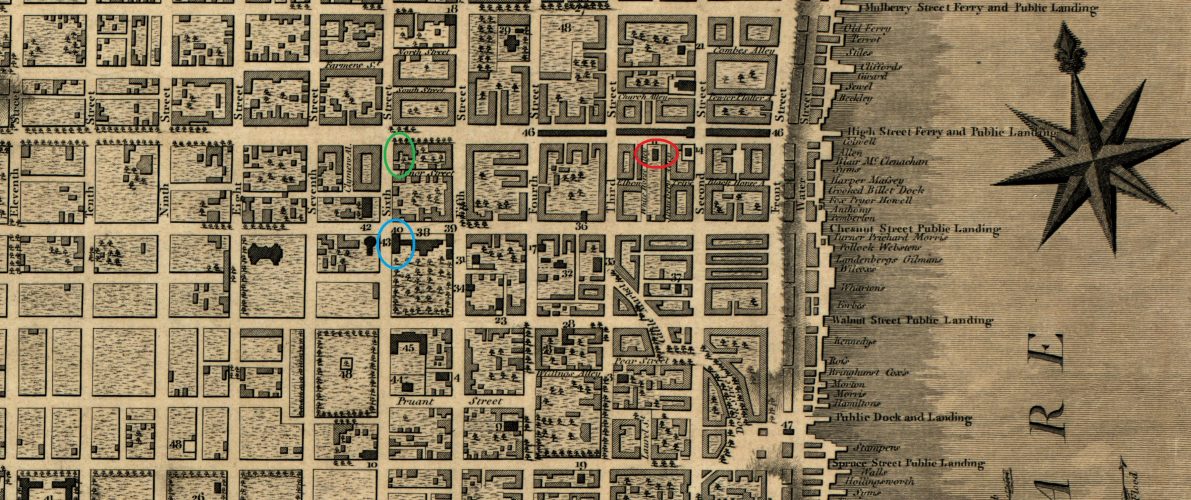

Notes—The map section in the header is from the Library of Congress’s copy of “This plan of the city of Philadelphia and its environs showing the improved parts,” as composed by John Hills, surveyor, engraved by John Cooke, and published in Philadelphia, 1797; it is a finely detailed map complete with a legend. The blue ellipse at the lower left indicates the building where Congress met (part of the Independence Hall complex), and the green ellipse above it is the site of the presidential house where both Washington and Adams lived (part of Independence National Historical Park). The red ellipse on the right indicates the First Church building which faces High Street (a very deep lot). Street names are indicated on the right by the name of the landing, such as “Chestnut Street Public Landing.” The long black boxes in the center of High Street are booths for vendors, thus the evolution to the current name, Market Street. At some point First Church moved west to the corner of Walnut and 21st Street. The article, “Market Street,” by Stephen Nepa in The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia is interesting and mentions residence locations of some fathers of the Revolution. The main source is W. Frank Craven’s biography in Princetonians 1776-1788: A Biographical Dictionary, 1981, as edited by Richard A. Harrison; a portrait is included in the article. Craven also wrote, “The Rebuilding of Nassau Hall,” in The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 41:1 (Autumn 1979), 54-68. Sprague’s Annals, vol. 3 and F. Dean Storms’s History of the Allentown Presbyterian Church Allentown, N. J. (1720-1970), Allentown: Allentown Messenger, 1970, were both informative. For an account of the Nassau Hall fire see, Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker, Princeton 1746-1896, 1946, 1973. Craven notes two journals of Clark’s military service have been published—one from May 1777 to late 1778 in New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, (1855), 93-110, and another beginning November 29, 1776 and ending in June 1777 was transcribed in the Princeton Standard, May 1, 8, and 15, 1863. The “Letter, John Adams to federal department heads ordering the relocation of government offices from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia, 15 May 1800,” is available on the Library of Congress website. The edition of the minutes used is Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its Organization A. D. 1789 to A. D. 1820 Inclusive, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publications, [1847].