The following excerpts are from the review article, “The Religious Condition of Holland,” as published in The Biblical Repertory and Theological Review 5:1, January 1833, pages 19-33. The writer of the article is J. W. Alexander according to the index of journals 1829-1870 compiled by Earl W. Kennedy and edited by Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center. The book reviewed is by Theodor Fliedner who was an Evangelical pastor at Kaiserwerth near Düsseldorf and an important figure for the development of nursing and hospitals as well as an influence upon Florence Nightingale. His eight-month tour of Holland and England was published in, as the title pages read, Collektenreise nach Holland und England (Collection Trip to Holland and England), 2 vols., Essen, Germany, 1831, complete with illustrations and an account of important theology publications at the time. The trip took place in 1823 and 1824 with a follow-up by Fliedner in 1829 to review his information for publication. The excerpts provide a sample of Dutch church life two-hundred years ago for comparison to today. Italicized text indicates quotes from Fliedner’s books as in the TBR&TR article.

Note the number of services on the Sabbath and during the week. Dutch and those of Dutch descent in North America might be surprised at the religious life of the Netherlands two-hundred years ago.

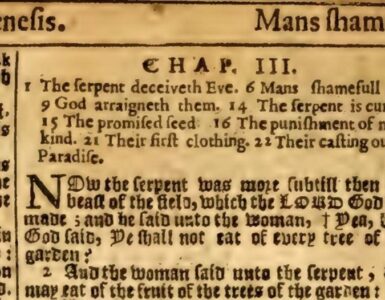

The header picture of a Dutch church is from pixabay.

Barry Waugh

In the years 1823 and 1824, the Rev. Theodor Fliedner, Evangelical Pastor in Kaiserwerth near Dusseldorf, Germany, made a tour through Holland, in which country he spent more than eight months. During this period, he made it his business to become accurately acquainted with the whole church-system of the Reformed Churches, and in order to bring down his statistics and narratives to the latest date, renewed his visit in the year 1829, previously to the publication of his Journal.…

The account of the Sabbath at Amsterdam is the more pleasing, as we are acquainted with the remarkable laxity of opinion and practice in relation to this ordinance, in the French and German churches.

The hum of the working-day, and the confused noise of business, which all the week prevail in every street, canal, market and dwelling of this commercial city, are now hushed. Solemn stillness every where reigns, and the Christian prepares himself for the Sabbath festival. From seven o’clock in the morning, at which hour the early service begins, until seven in the evening, when the latter service ends, the streets are filled with church-goers. There is preaching five times in the day; at seven, ten, twelve, two, and five o’clock, by more than fifty ministers; in ten churches by twenty-eight Dutch Reformed, in two by five French Reformed, in three by nine Lutheran, in one by three Remonstrant, in one by five Mennonists, and in two by five English preachers.

The author, in connexion with these statements, is naturally induced to long for the time when the sound of labour and of merriment shall not profane the Lord’s day in Germany.

The public preaching of the Dutch ministry would seem to resemble what is common in America, rather than the rhapsody and declamation of the German pulpit. Mr. Fliedner complains that the sermons are too doctrinal, too dull, and too long. An attempt to enliven their discourses begins to be made, by a number of preachers, in imitation of their great pulpit orator, Van der Palm. The Christian knowledge of the congregations is much promoted by the regular afternoon sermon, upon the Heidelberg Catechism, which, as among our brethren of the Reformed Dutch Church in the United States, is gone through once a year.… There are, also, in a number of the cities, Poor-sermons, intended specially for the large class of poor persons, who are ashamed of their dress, and who attend upon these in their ordinary clothing. To the Reformed of Holland, what are called Confession-sermons are peculiar. They are delivered four times a year, on Sunday, in all the churches, partly for the confirmation of those who have made a profession of their faith, partly for the edification of the numerous youth who have not yet done so. As there is no constraint used with regard to a public profession, it is the case with many in Holland, as in America, that they pass through life without being church-members.

Psalmody and church music receive in Holland a regard which is unknown in other countries, and their collections of spiritual songs are said to be unrivalled.…

The religious instruction of youth is committed chiefly to persons called Catechism-masters, or, in the case of girls, Catechism-mistresses, and who pursue this as a regular calling. This is under the general supervision of the ministry, but it is thought by Mr. Fliedner, that the subject is much neglected; even more so than in Germany. In the larger congregations, the sick of the middle and lower classes are visited by persons appointed for that purpose, called Siekentroosters who are selected from the catechists. In the smaller congregations, and throughout the country parishes, the pastors perform this duty with fidelity. In all these respects, the usages of ancient times are regarded. The opposition of the Reformed to prelatical confirmation, led them to require a simple confession of faith, in order for admission to the Lord’s table. If we may credit the accuracy of our traveller, there is not even that previous instruction or discipline which is common in Scotland. The want of religious instruction threatens the purity of the Dutch Reformed churches. In those of the Baptists of Holland, it has opened a door for deplorable error and infidelity.…

The celebration of the Lord’s Supper is conducted in a manner similar to that which many American churches have derived from our Scottish ancestors. The officiating minister is seated at the middle of a long table, covered with white cloth, and around him are gathered the communicants, without distinction of rank; the king himself appearing in the midst of his subjects. At Rotterdam, where the author attended this solemnity, in the church of the Rev. Mr. Scharp, there were successively twenty-eight tables, each of which numbered not less than forty-eight persons. The service occupied five hours, and the Sacrament was at the same time administered in five other churches, and again repeated in the same, a week later. This is in pursuance of a Synodical order of 1817, which prescribes such an administration once in every three months. About the beginning of the Reformation, the communion took place only twice a year, as is now the case in Scotland.…

As an indication that new theology, with a corresponding tenderness towards errorists, is gaining ground in Holland, we may observe, that the formula of subscription for candidates runs thus: that the probationer “heartily believes the doctrine comprehended in the symbolical books, agreeing with God’s holy word.” This ingenious participial phrase furnishes a happy postern for the escape of such as happen to dissent from the rigour of the articles of the Belgic Confession. “If we interpret the word agreeing (said a distinguished member of the Synod to Mr. Fliedner) as meaning because, it says too much, if so far as, it says too little.”…

Among the authors who have most influenced the opinions of the Reformed, there are two who may be compared with the German Ernesti and Michaelis. Like these, the Hollanders, Van Voorst and Van der Palm, have opened the way, far beyond their own intention, for the flood of neology. Van Voorst was Professor of Theology at Franeker, from the year 1778, at Leyden from 1800, and in 1827 retired from public life. Van der Palm was, from 1799 to 1804, General Director of public instruction, and since the year 1805, Professor of the Oriental languages at Leyden. Van Voorst regards the grammatical interpretation of the Scriptures as all-sufficient; and in this respect may be considered as following the track of Grotius and Ernesti. Like the latter, he rejects the idea, that any experimental acquaintance with divine things is required in an interpreter. His scholars go even further than himself in these opinions, and find less and less of evangelical meaning in the Bible. Van der Palm is, like Michaelis, by no means disposed to reject openly the system of doctrine hitherto current; on the other hand, he manifests profound reverence for the word of God, and is less disposed, even than the great German, to sneer at the miracles of the Scripture. Yet he coincides too much with him in the attempt to explain away all that is supernatural. This renders his influence most deleterious. A third name is that of the late Professor Muntinghe of Groningen. Distinguished rathfer in historical than exegetical science, and somewhat decided in defence of general truth, he was inclined to make concessions to the adversary. Bosveld and Van Kooten are inclined to rationalism, as is Van Hengel, a pupil of Van Voorst, whom he succeeded in the chair of theology at Leyden. In his acute and elegant interpretations, he pursues the method which has already done its work in Germany, and begins to operate in America; he fixes the attention on the mere grammatical exposition of the text, or, to use the expressive language of a German writer, “does not conduct his disciples into the holy place of the saving Word, but with learned discourse detains them in the contemplation of the outer gate and its carved-work, until the time for entrance is flown.” A holier spirit breathes in the publications of Stronck, and of Heringa and Royaard, Professors at Utrecht, and still more in those of the Baron de Geer, Professor at Franeker, a learned young nobleman, to whom not only Friesland, but all Holland, is anxiously looking for a noble defence of ancient faith and piety.…

Education is in Holland a state affair, and not as in Germany, connected with the ecclesiastical polity. Upon the restoration of the House of Orange, it received new patronage and a favourable impulse. Mr. Fliedner laments, that it is too little regulated by a spirit of religion, that emulation is made the predominant motive, that schools are opened and closed without prayer, and conducted without the reading of the Bible, and that the popular school books are merely moral, and not Christian. The first classical instruction is communicated in the Latin schools, to which boys go from the elementary schools, at the age of ten years. The youth proceeds thence either to the Athenaeum or the University. The Latin language is used in lectures and in the replies of the students. The university students are represented as being actuated by great literary enthusiasm. The academical course extends through the whole year, with the exception of a summer vacation of three months. Since 1820, the king of the Netherlands has made the courses at the universities free to all theological students, making up the loss of fees to the professors. He also makes a present of two hundred florins annually to every minister’s son who is pursuing his education. All students, in whatever faculty it may be, bring to the officers of the university their church certificates; yet they are under no particular spiritual or pastoral care, which the author justly censures.…

[The author of the article concluded that] Our readers must already have observed, that since the date of the volumes upon which we have been commenting, great political changes have taken place in Holland and the Netherlands. These cannot but have communicated a shock to the ecclesiastical structure of the Reformed Church, and we await, with solicitude, some satisfactory tidings from a land endeared to us by so many recollections of noble daring in the cause of liberty, and yet nobler enthusiasm in the restitution of primitive faith and order.