Samuel was born Reformation Day, October 31, 1769, in Dover the eighth of nine children and the fourth son of John and Margaret (Millington) Miller. Margaret was the daughter of an English sea captain who abandoned the uncertainties of sailing the seven seas for living on the good earth as a planter in Maryland. John Miller was minister of the Presbyterian churches in Smyrna and Dover Delaware and the household lived on a hundred-acre farm. During the division of the Presbyterians into Old and New Sides, 1741-1758, he was a member of the Old Side Presbytery of New Castle. The Sides are not the same as the Old and New Schools. The Sides divided over interpretation and application of the Adopting Act of 1729 concerning subscription to the Westminster Confession. An associated issue was itinerant evangelists conducting revival meetings within presbyteries of which they were not members. The Old Side believed in full subscription to the Confession while the New opposed subscription or believed in a greatly limited commitment to its summary of doctrine. The Old Side held to strong church judicatories governed by presbyters that directed their churches with a thorough commitment to the Westminster Standards and presbyterian polity.

Samuel was born Reformation Day, October 31, 1769, in Dover the eighth of nine children and the fourth son of John and Margaret (Millington) Miller. Margaret was the daughter of an English sea captain who abandoned the uncertainties of sailing the seven seas for living on the good earth as a planter in Maryland. John Miller was minister of the Presbyterian churches in Smyrna and Dover Delaware and the household lived on a hundred-acre farm. During the division of the Presbyterians into Old and New Sides, 1741-1758, he was a member of the Old Side Presbytery of New Castle. The Sides are not the same as the Old and New Schools. The Sides divided over interpretation and application of the Adopting Act of 1729 concerning subscription to the Westminster Confession. An associated issue was itinerant evangelists conducting revival meetings within presbyteries of which they were not members. The Old Side believed in full subscription to the Confession while the New opposed subscription or believed in a greatly limited commitment to its summary of doctrine. The Old Side held to strong church judicatories governed by presbyters that directed their churches with a thorough commitment to the Westminster Standards and presbyterian polity.

Samuel’s early education in preparation for college was with two older brothers under the direction of his father. He then entered the University of Pennsylvania in 1788. The university was during its years before Miller attended influenced by Francis Alison, a leader of Old Side Presbyterians. Mark Noll described Alison as “an Old Side stalwart” (Princeton & the Republic, 40). Alison’s work at the university was influential extending 1752-1779 with his positions including master of the Latin school, rector of the academy, teaching moral philosophy, professor of Greek and Latin, and vice provost. But at the time Miller attended the provost was John Ewing, pastor of First Church, Philadelphia. Ewing was taught in Alison’s New London academy then graduated the College of New Jersey (Princeton, New Side). Had Samuel been encouraged to go to University of Pennsylvania by his father because of its Old Side history during Alison’s years anticipating his continued influence through his students? Possibly, but Ewing’s views were not so rigorous as Alison’s. Young Miller, he was nineteen, graduated with high honors July 31, 1789 after only one year of attendance. As salutatorian he delivered a Latin oration against the lack of concern for educating women in his time. Note that this was the year after the United States Constitution was ratified and he was speaking of equality for women regarding education. Degree in hand, he returned to Dover.

Dover would always be home for Samuel Miller because he enjoyed the family farm and country life. John tutored his brilliant son in theology in preparation for the ministry. Licensure involved a multi-step process. He began trials at Rockawalkin Church in Somerset County, Maryland, April 20, 1791, delivering his doctrinal sermon from 1 Corinthians 15:22—

For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.

The weighty doctrine of federal headship correlates the fall and sin with its defeat through the perfect righteousness and atoning work of the resurrected Christ. The next step for licensure was in June, followed by further examinations during the fall meeting in October to complete the process. He was tested regarding personal piety, Latin, Greek, rhetoric, logic, natural and moral philosophy, as well as divinity. At the October meeting he delivered what was described as a “popular sermon.” During this same meeting Samuel’s recently deceased father was remembered for his forty-three years of ministry to his congregations and for the presbytery.

The usual procedure for continuing his study of divinity would have been to find a local minister and pick up where his father’s instruction ended, but in November, Miller made his way west to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Carlisle was a community settled and developed by Scotch-Irish Presbyterians; it was a western enclave for Presbyterians who felt disenfranchised by the Eastern elite. He made the move with approval of his presbytery to study with Charles Nisbet (1736-1804), the president of Dickinson College. Nisbet could speak nine languages, was a member of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, and a defender of rigorous Calvinism. Nisbet had recommended John Witherspoon for the College of New Jersey Presidency. Miller commented in his biography that in the evenings for two or three hours he would meet in Nisbet’s home to inquire

on whatever subject I might desire information, whether in Theology or Literature, ancient or modern, I had but to propose the topic, and suggest queries, to draw forth everything that I wished. (Life, 1:58; “I” has been substituted for “he”)

Nisbet’s knowledge was encyclopedic. Miller had expected Professor Nisbet to be cold and distant, but instead he found the Scotsman and his family affable and hospitable. Nisbet was as important doctrinally for Miller, other than his father, as was William Graham for his future colleague at Princeton Seminary, Archibald Alexander. When Nisbet died in 1804, the search for a replacement led to Miller, but he turned it down. Miller would publish in 1840, Memoir of the Rev. Charles Nisbet, D.D., but when he was asked to edit Nisbet’s lectures for publication, he turned down the request.

In 1792 Miller was invited to candidate for a church on Long Island, but when he stopped for a visit in New York he was invited to preach in a church. That fall, he was issued a call by a unanimous vote of the Collegiate Presbyterian Church of New York to join ministers John Rodgers and John McKnight. Miller commented at the time that he had wanted only to pastor a country church (Long Island was rural at the time), but he accepted the call and was ordained and installed June 5, 1793. His love for the Delaware family farm led him to the opportunity on Long Island.

From the beginning of his New York ministry, Miller was not despised for his youth but instead proved an exemplary colleague. The local Reformed ministry included not only Miller’s pastoral colleagues at Collegiate, but also John M. Mason (Associate Reformed) as well as Reformed Dutch pastors John H. Livingston and William Linn. It was really a golden opportunity for Miller to serve the Lord with such experienced colleagues. He often spoke in other churches and delivered lectures before societies. Miller expressed his opposition to slavery and promoted gradual emancipation when he spoke to his fellow members of the New York Society Promoting the Manumission of Slaves in 1797. He married Sarah Sergeant October 24, 1801 with the service conducted, as was mentioned, by John Ewing. Sarah’s father was Jonathan D. Sergeant of Philadelphia, who was a member of the Continental Congress and an attorney general of Pennsylvania. One characteristic of Miller mentioned by biographers was his refinement and gentlemanly demeanor; he was always prim and proper. In 1827 he would publish Letters on Clerical Manners, because of his concern that students in the seminary needed to be well mannered in their ministries.

As his work continued, Miller took on additional duties including connectional work with the presbytery, synod, and General Assembly. In 1806 he was elected moderator of the General Assembly that convened May 15, 1806 in First Church, Philadelphia. Retiring moderator James F. Armstrong opened the assembly with a sermon from John 3:16,17. After Miller appointed committees for reviewing synod records, a committee was appointed to consider breaking the General Assembly into two or three general synods with each one including subordinate synods. The general synods would meet annually and the General Assembly would convene at “more distant periods.” The committee reported that having southern, eastern, and western general synods might increase convenience but deemed it “inexpedient at present” to change the Constitution. The reason behind switching assembly meetings to less frequent than annual was travel expenses. A committee was appointed to figure out how to improve the situation with travel funding. If the general synod idea had been adopted there would have been five levels of church courts—session, presbytery, synod, general synod, and general assembly. Would this have offered any greater convenience? Behind the general synod idea, possibly, were those who thought the Philadelphia-centric denomination did not understand the different situations of the west and south. Eliphalet Nott delivered the annual missionary sermon from 1 Corinthians 15:58. A report was adopted encouraging parents to educate their sons in such a way that they learn not only general subjects, but also develop their piety with an eye to the ministry. This report resulted from concern that presbyteries were short of ministers and in some cases the situation was dire. A committee’s report was adopted setting forth the plan to pool funds at the assembly for distribution to commissioners according to their actual expenses based on mileage. There were also several items of business concerning the relationship with Congregationalists established by the Plan of Union in 1801—some were positive items, while others expressed concerns. The location of assembly meetings continued to be a sore point. A motion to hold the next assembly in Alexandria, Virginia instead of Philadelphia “was determined in the negative,” thus showing the denomination’s tendency to ecclesiastical federalism with its government in Philadelphia as had been the U. S. Government for several years. Samuel Miller adjourned the judicatory on the twelfth day, minus Sabbaths, May 26. His moderator’s sermon in 1807 would be from Philippians 3:8

Yea, doubtless, and I count all things but loss, for the excellency of the knowledge of Jesus Christ my Lord.

May 1811 was an important year of transition not only for Miller but also the Presbyterian Church. Dr. Rodgers died on the seventh of the month leaving a great vacancy in New York that would be difficult for Miller to fill. Rodgers had been like a father to him with the two serving together for almost twenty years. He preached a touching and impressive memorial sermon for his venerable colleague and then honored his life with Memoirs of the Reverend John Rodgers, D.D. 1813. The biography is more than just an account of Rodgers’s life because it includes general history information about the Presbyterian Church. Later in May, the General Assembly convened in Second Church, Philadelphia, with New York Presbytery represented by Miller, John B. Romeyn, and ruling elders John Mills and Divie Bethune. Another committee appointment required deliberation on

the subject of ordaining ministers sine titulo [without a call]…to consider and present to the Assembly the draught of an order which it may appear to them that the Assembly should adopt on the subject, with the principles derived from our constitution, on which such decision should be grounded.

Miller’s committee report was replaced by a substitute after extended discussion. The substitute determined that Presbyteries were to ordain candidates without calls to particular churches only with the approval of their respective synods or the General Assembly, thus allowing sine titulo ordination on a case-by-case basis. But this was not the only committee to which Miller was appointed. He was on a committee to report on the use of agents to solicit donations for the Theological Seminary scheduled to open in Princeton the next year, the report was adopted with Miller included on the list of agents. Added to his duties were preaching the annual missionary sermon; serving on a committee that assessed a catechism by Samuel Bayard acceptable for use by the Presbyterian Church; he joined other commissioners to consider the problem of abuse of spiritous liquors (spirits or distilled liquor) and bring recommendations to the assembly regarding solutions; and he joined two other commissioners on a committee for the purpose of determining the steps “the Church [should] take with baptized youth, not in communion, but arrived at the age of maturity, should such youth prove disorderly and contumacious.” Another committee appointment involved writing the annual Narrative of Religion, which was a report on the growth and extension of the Presbyterians. For some reason the Narrative was debated extensively. At the time the denomination had 460 ministers serving 820 churches that were represented in the assembly by 85 commissioners. There were plenty of commissioners, but it seems Samuel Miller was the most popular committee appointee. It was a busy year at the assembly with the most important actions associated with opening the Theological Seminary at Princeton.

When Archibald Alexander was inaugurated the seminary’s first professor in August, 1812, Miller delivered the sermon. The next year, Miller became chair of ecclesiastical history and church government with his induction September 29. Pairing the two provided a balance to the faculty. Miller’s Old Side influnces combined with Alexander’s New Side training under William Graham created an educational environment in which applied Westminsterian doctrine brought together head and heart knowledge. These two full professors taught for a decade before Charles Hodge joined them in 1822 as the third professor. The two taught 247 students including: John Breckinridge, William B. Sprague, Benjamin Gildersleeve, Samuel L. Graham (William’s son), John Ross, William A. McDowell, William Henry Foote, Eli W. Caruthers, and Albert Barnes. The pair were colleagues for thirty-five years until Miller passed away January 7, 1850, then Alexander died less than two years later. Alfred Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia reports that Miller’s funeral drew ministers and residents from all over the region and Archibald Alexander delivered the sermon.

Samuel Miller is buried in the Princeton Cemetery of the Nassau Presbyterian Church. Sarah survived until 1861 and is interred next to him. It appears from an online photograph of their graves a child is buried next to them. He was honored with the Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) by both Union College and then the University of Pennsylvania in 1804. The Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) was given in 1811 by the University of North Carolina. Miller had been considered as a candidate to succeed Joseph Caldwell as president of U.N.C. The number and identities of all his children has proven elusive but here are the ones I could determine. I could have checked the U. S. Census which likely would have helped—Margaret (1802-1838, married John Breckinridge), Jonathan Dickinson (1810–1891, went by Dickinson), Samuel, Jr. (1816-1883), Elihu Spencer (1817-1879), John (1819-1895), and possibly Sarah. Estimates of the number of children I located are from nine to eleven children.

Barry Waugh

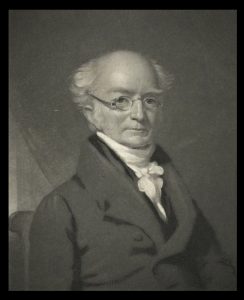

Notes—The header titled “Old Farm by the River,” 1885, and the portrait of Miller are from the New York Public Library Digital Collection; the farm pictured is not Miller’s but it possibly expresses Dr. Miller’s fondness for the rural life. For information on the Old and New Sides see on this site, “What are the Old Side & New Side?” For the definitive bibliography of Miller see, “Samuel Miller, D. D. (1769-1850): An Annotated Bibliography,” by Wayne Sparkman in The Confessional Presbyterian 1, 2005, 11-42; this issue of TCP is no longer available but can be located in a theological seminary or college library. The same issue of TCP has Miller’s sermon “Faith Shewn by Works: A Sermon on James 2:18.” Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary publishes TCP. Samuel Miller, Jr., published in two volumes The Life of Samuel Miller, D.D., LL.D, in 1869; it is compiled from Dr. Miller’s notes, journals, and correspondence. Ready for download are several of Dr. Miller’s multitude of publications on the Log College Press website. Regarding Dr. Miller’s father John and his Old Side affiliation, see the biography in Sprague, Annals, vol. 3. “Charles Nisbet (1736-1804),” on the Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections site is a good biography; my information about him in this post is primarily from this site; the archives have a collection for him that I believe includes the lecture notes Miller was asked to publish. Two other titles are a book released this year, Allen M. Stanton’s Samuel Miller (1769-1850): Reformed Orthodoxy, Jonathan Edwards, and Old Princeton, Peter Lang, 2022; and James M. Garretson’s an Able and Faithful Ministry: Samuel Miller and the Pastoral Office, Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2014. See also, The Presbyterian Magazine Vol. 2, 1852, “Licensure and Ordination of Samuel Miller,” 179-183, also in the volume is “Biographical Notice of Rev. Samuel Miller, D.D.,” 510-517. For information about Charles Nisbet of Dickinson College, see the post on this site, “Robert Davidson, Pastor, Professor, and Patriot.” Mark A. Noll’s book is Princeton and the Republic 1768-1822, Princeton: PUP, 1989; a comparison of Alison and Witherspoon is within pages 30-49. A Discourse, Delivered April 12 , 1797, at the Request of and before the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission [release] of Slaves, and Protecting Such of the as Have Been or May be Liberated, New York: T. & J. Swords, 1797. The minutes used Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its Organization A. D. 1789 to A. D. 1820 inclusive, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, [n.d.]. David B. Calhoun’s two volumes Princeton Seminary, published by Banner of Truth, 1994, 1996, include a biography of Samuel and Sarah 63-65 & 67-68. See in Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol. 4, Lodge-Pickens, the article titled “John Miller” who is Dr. Miller’s father, also includes Dr. Miller, and his brothers Edward and John; Dr. Miller’s sons, Samuel, Jr., John, and Elihu Spencer (a physician). Dr. Miller wrote a biography of his brother Edward, M.D. that is in The Medical Works of Edward Miller, 1814. Edward made contributions to understanding Yellow Fever when it visited Philadelphia in 1793, and he was a friend of Benjamin Rush.