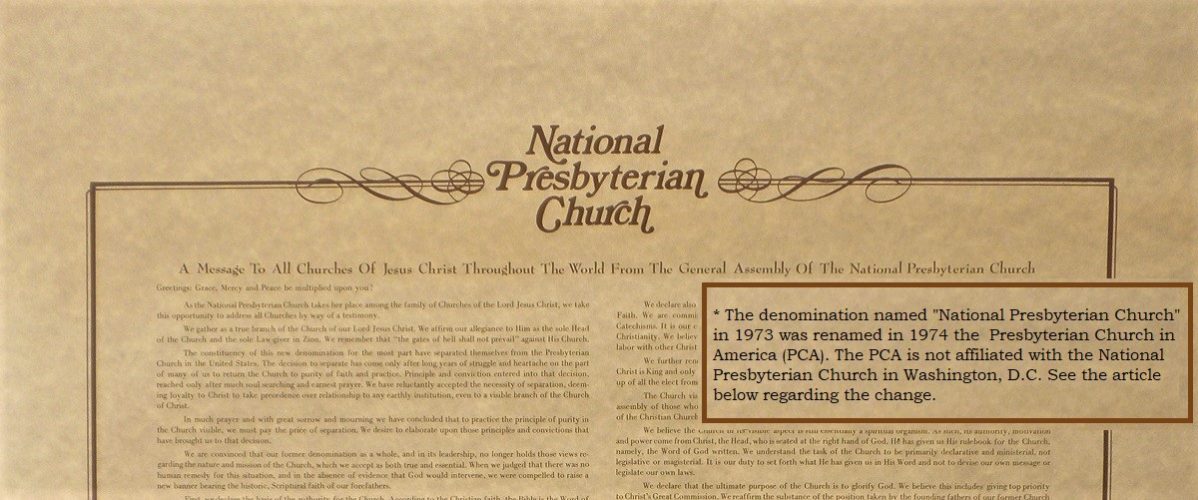

This year is the semi-centennial of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Fifty years is a long time with many members having entered the denomination over the years while others alive in 1973 have passed on. To remember the founding, some of the early history of the PCA is provided below. Pictured in the header is a broadside composed in 1973 by Ruling Elder J. Ligon Duncan, Jr. It appears to be a document that was laid out on a table at a gathering so individuals could sign it, but this was not the case. However, before continuing with the story of the broadside, the question of the relationship of the National Presbyterian Church to the PCA must be answered. For several years there were members of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) that were increasingly dissatisfied with the position of their denomination regarding the doctrines of Scripture and issues associated with its interpretation and application. Along with this was minimalization or neglect of the teachings of the Westminster Standards subscribed to by all church officers. With reference to Scripture, one signer of the broadside told me that when he confronted one of his professors in a denominational seminary asking him while pointing to a Bible, “Is this the Word of God?,” that after circling around an answer finally said “No.” This was one professor; not all the professors in the seminaries took his position. If ministerial candidates were being taught by some educators that Jesus’ words in John 17:17 were in fact not true, then the future of the denomination as a confessional church faithful to Scripture and the great commission was in question. The concerned Presbyterians made their case through preaching, special informational meetings, and publications increasing their number sufficiently to take action because the divergent views could not continue to coexist in one body. Leaders of the concerned Presbyterians organized the Advisory Convention of the Continuing Presbyterian Church to meet in Asheville, North Carolina, August 7-9, 1973. An important action by the Advisory Convention was calling the first general assembly for the Continuing Presbyterian Church.

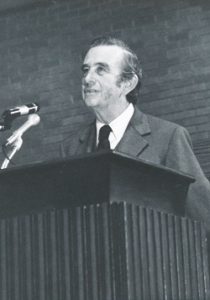

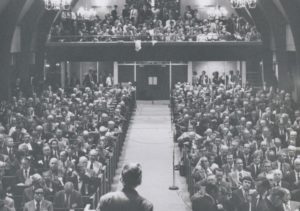

It was a cloudy but dry nearly seventy-degree evening when commissioners gathered December 4, 1973 in an earlier sanctuary of Briarwood Presbyterian Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The Advisory Convention had selected Ruling Elder Jack Williamson of First Church, Greenville, Alabama, convener for the meeting. He was an accomplished Christian jurist who ruled well in his church and was an important contributor to the connectional judicatories as well as the continuing church movement. Respect for him yielded election by acclamation to moderate the first assembly. Also elected by acclamation to continue their temporary positions were Teaching Elder Morton H. Smith as stated clerk and Ruling Elder John Spencer as recording clerk. Notice that the assembly elected a ruling elder for moderator with two of the three assembly offices held by ruling elders. It is an acknowledgement of the two office view of church leadership—the elders function in a ruling or teaching capacity and they work together with the diaconate in its mercy ministry. For the most part, at least through the nineteenth century, the history of American Presbyterianism shows that moderators were ministers, as were clerks. For example, minister-educator-founding father John Witherspoon was moderator of the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in 1789, but due to ill health he quickly passed the gavel to John Rodgers; when the Presbyterians in the southern states in 1861 formed the church that would become the PCUS, the minister-educator Benjamin M. Palmer was the moderator. Thus, the new church showed its commitment to rule by elders as Moderator Williamson called the commissioners to order at 7:30.

One particularly important item of business was selection of a better name for the church than Continuing Presbyterian Church. Three names proposed were—Presbyterian Church of America (previously used briefly by the Orthodox Presbyterian Church), Presbyterian Church in America, and the name that went on to be selected, National Presbyterian Church. In addition to name selection were decisions concerning the governance and direction of the new church such as presbytery boundaries, general assembly committees, inter-church relations, the adoption of doctrinal standards, the examination of ministers, and supplying insurance for ministers. Also, the broadside was included in the Inter-Church Relations committee report given by its chairman, Teaching Elder G. Aiken Taylor. The draft broadside was adopted with the title “A Message to All the Churches of Jesus Christ.” Commissioners were given opportunity to sign the draft, but in the end, “A Message to All the Churches” would be a document composed with signers of the draft and signatures gathered by Elder Duncan and his wife Shirley, then cut and pasted onto the page that became the broadside. It was a busy assembly as the elders laid the foundation of the church.

Sometimes judicatory actions have to be reconsidered because of errors, or because implications of the actions were not fully grasped, so when the General Assembly convened in First Presbyterian Church, Macon, Georgia, 1974, the commissioners had to change the denominational name because the National Presbyterian Church in Washington, D. C. had the name first. Moderator Erskine L. Jackson, pastor First Church, York, Alabama, was faced with seventeen possible names from which three were chosen for the final vote—National Reformed Presbyterian Church, International Presbyterian Church, and American Presbyterian Church. The name selected was National Reformed Presbyterian Church, but it was short lived because later in the meeting a motion to reconsider was adopted, then eight names were proposed. Following a motion requiring two-thirds vote to select the new name, the one adopted was Presbyterian Church in America. Thus, the name was Continuing Presbyterian Church, which was changed to National Presbyterian Church, then briefly it was National Reformed Presbyterian Church, but then finally it became Presbyterian Church in America. So, that is what the name National Presbyterian Church has to do with the naming of the Presbyterian Church in America.

Returning to the broadside, it was printed by Elder Duncan in his shop creatively named “A Press” because it had a press. The broadsides were distributed at the 1974 General Assembly with a copy framed and presented to retiring moderator Jack Williamson by Stated Clerk Morton Smith. When the PCA General Assembly was held in Greenville, South Carolina in 2013, the Duncan family had the broadside reprinted with the name changed from the no longer used name, National Presbyterian Church, to Presbyterian Church in America.

Published with the broadside was a booklet that includes statistics about the signatories of the broadside. There are 296 signatures on the document including the three officers at the beginning. The minutes of the 1973 meeting state the commissioner count was 208 ruling elders and 179 teaching elders for a total of 387 with 54% of the commissioners ruling elders. Nearly a hundred commissioners did not sign “A Message to All the Churches,” but the omissions were more likely due to lack of opportunity than conviction. Overwhelmingly, as one might expect, the teaching elders enrolled at the first assembly were born in the South. Of the 176 ministers in attendance, 110 were born in southern states, 49 were born north of the Mason Dixon Line, nine in other states, and eight were foreign born. For the South, North Carolina had the largest group providing twenty of its sons; Georgia and Mississippi each were represented by fourteen; thirteen claimed Virginia their natal state; Alabama’s sons numbered ten; the Sunshine State managed nine; seven each came from Louisiana and Tennessee; South Carolina, the Palmetto State, provided five; Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas had three each; and two were born in Maryland. In comparison, the state with the most in the North was the Keystone State of Pennsylvania with nine; followed by Michigan’s eight; the Garden State of New Jersey had seven; The Buckeye State provided five; New York and West Virginia each contributed four; the abutted states of Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa each provided two; and Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and Washington, D. C. had one each. Other states included California with four; Colorado sent two; and Missouri, Oklahoma, and Nebraska each had one. Two teaching elders’ places of birth could not be determined. International birth locations include Brazil, Canada, Hungary, and Ireland with one each, and Japan and Korea with two each. The number of institutions granting under-graduate degrees to the men that became teaching elders is 79, so the tally presented here will be limited to the top ten colleges. Number one is Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi, with 30 graduates; followed by King College at a distant second with 13; and then Davidson College with 11. The first public university making the top ten is the University of Georgia’s eight graduates, followed by Presbyterian College in South Carolina providing six. The University of Miami in Florida and Wheaton College each graduated five; Columbia Bible College and Maryville College provided an education for four; and tenth place goes to the University of Mississippi with three graduates. All of the top ten undergraduate institutions are in the South. The remaining undergraduate schools include ten colleges having two graduates each and fifty-eight with one graduate each. The seminary (i.e. may be a true seminary, a graduate school, or an institute) with the most graduates was Columbia Theological Seminary with 83; next Reformed Seminary has 34; followed by Union in Virginia and Westminster in Philadelphia with eleven each; a total of ten graduated from the three seminaries Austin Presbyterian, Fuller, and Princeton; and seven additional seminaries had two each, followed by eight seminaries with one each.

The spread of ages reflected by the year of ordination shows some interesting aspects of the body of ministers constituting the first assembly. It should be remembered that in this statistic are included men called to the ministry in the later years of their lives, but these ordinations generally constitute a very small number and its affect on the analysis would be minor. William A. McIlwaine holds the honor of being the man with the longest service as a teaching elder at fifty-four years having been ordained in 1919. J. Kemp Hobson was ordained in 1920 and was the man with the second longest ministry. Also in the twenties (1920-1929) were Wick Broomall and John Bowling, both ordained in 1929. The forties add twelve more ordinations. The era of President Eisenhower, 1950-1959, provided forty-eight pastors, and the sixties, a turbulent time in America that saw the parachurch Jesus movement, had sixty-two young men ordained. The four years of 1970-1973 added thirty-nine names to the roll of commissioners. If one guessed at the spectrum of ages for teaching elders at the First Assembly, it might be thought it would be weighted towards fathers of the church, but the younger men constituted 149 based on the years 1950-1973. A tally of the presbyteries that ordained the ministers is not necessary because the ordaining judicatories were overwhelmingly, as one would expect, PCUS presbyteries. There were a few ministers from the UPCUSA (the name of the PCUSA in 1973 after uniting with the UPCNA in 1958), ARPC, and the RPCES (would unite with the PCA in 1982). Since many churches had separated from the PCUS earlier in 1973, several of the teaching elders at the First General Assembly had been ordained by PCA presbyteries. A final note that readers might find helpful is the sixteen original presbyteries were Calvary, Central Georgia, Covenant, Evangel, Gold Coast, Grace, Gulf Coast, Mid-Atlantic, Mississippi Valley, North Georgia, Tennessee Valley, Texas, Vanguard, Warrior, Western Carolinas, and Westminster. These presbyteries included 260 churches with 41,232 members. A list of the General Assembly moderators beginning in 1973 as well as digitized copies of the assembly minutes are available on the website of the PCA Historical Center. See the blue categories under the banner at the top of the homepage. All pictures were provided by the PCA Historical Center.

Also on Presbyterians of the Past are the following articles about the PCA 50th anniversary:

“South Carolina Presbyterian History,” posted January 20, 2023, provides a list of articles on this site about Presbyterianism in the Palmetto State. If we all knew more about our Presbyterian heritage, we would be better equipped to direct the PCA according to Scripture and the Westminster Standards.

“South Florida Presbytery, 50th Anniversary of PCA,” posted February 3, 2023, tells about Daniel Iverson’s ministry founding Shenandoah Presbyterian Church in Miami, Florida, and gives history regarding the establishment of South Florida Presbytery.

“50th Anniversary PCA and OPC, Christianity and Liberalism, J. G. Machen,” posted May 29, 2023, rewinds to an article published about J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism in 1985 and looks to the possibility of the PCA and Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) becoming one denomination.

Barry Waugh