While skimming titles on the shelves of one of the rare businesses known as a used bookstore last week, I came across a short section of South Carolina items. The spine garnering my attention was a slightly sunned copy of Jonathan H. Poston’s The Buildings of Charleston A Guide to the City’s Architecture, published by University of South Carolina Press for the Historic Charleston Foundation in 1997. Admittedly this is an old book to be reviewing, but I think its value warrants this online reminder and used copies from online vendors keeps them available. If you are interested in South Carolina history and cannot purchase a copy, then the county libraries in the state often have historical-genealogical collections, so copies of Buildings and other specialized books can be found for reference use.

While skimming titles on the shelves of one of the rare businesses known as a used bookstore last week, I came across a short section of South Carolina items. The spine garnering my attention was a slightly sunned copy of Jonathan H. Poston’s The Buildings of Charleston A Guide to the City’s Architecture, published by University of South Carolina Press for the Historic Charleston Foundation in 1997. Admittedly this is an old book to be reviewing, but I think its value warrants this online reminder and used copies from online vendors keeps them available. If you are interested in South Carolina history and cannot purchase a copy, then the county libraries in the state often have historical-genealogical collections, so copies of Buildings and other specialized books can be found for reference use.

The attractive 717-page book is wrapped with a color jacket adorned with an image of an oil-on-canvas painting by West Fraser titled, “View from First Scots.” After a page telling readers how to use the book there is a brief chronology of Charleston history, then Poston directs readers to unique factors in the city’s architecture with introductory articles that discuss Charleston’s lovely ironwork, the unique design of the Charleston single house, and some of the old burial grounds in the city. The pages are printed on slick paper for the best reproduction of the hundreds of black-and-white photographs included for reference. Each page of the extensive catalog of buildings has a column of text with an abutting column of images illustrating the location described. The guide has nine chapters with each one offering information for a district of the city. The street numbers are listed in sequence so users can readily determine the building at the address in the book as they visit the structures, but as Buildings mentions, street numbers do change and the author notes some of these changes.

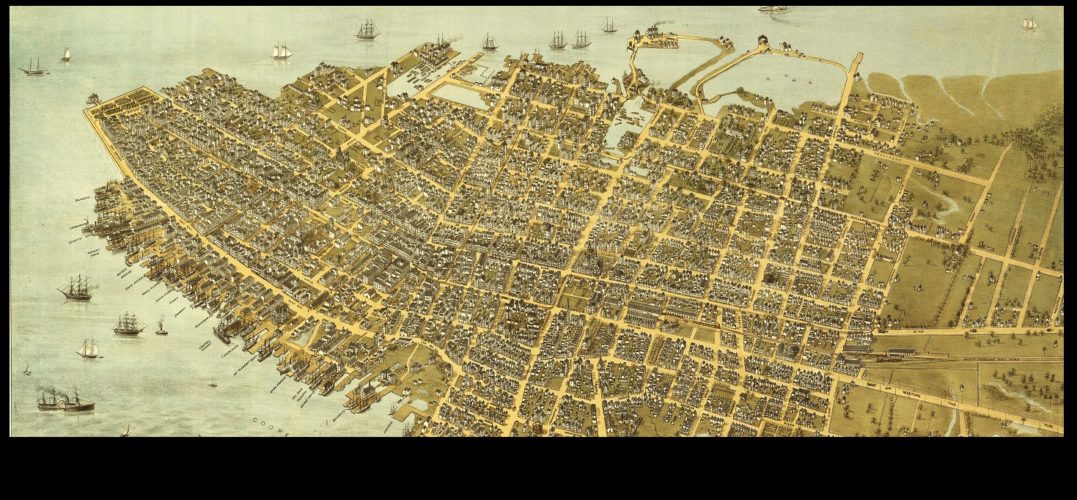

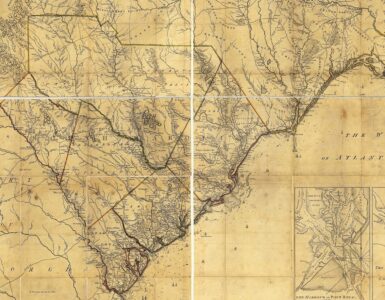

The first chapter is “The Walled City: Charleston’s Architectural Beginnings,” which includes in its area the city landmark, Rainbow Row, and the wharf district on the Cooper River. I did not realize that the foundation structure of Adger’s Wharves (named for James Adger, 1777-1858) dated to as early as 1735. A possibly familiar Charleston business for those who read old books may be the publisher-binder-stationer Walker, Evans, & Cogswell (earlier simply, Walker & Evans) that was located at 3 Broad Street. The company included among its Presbyterian publications Louisa Cheves Stoney’s Autobiographical Notes, Letters and Reflections by Thomas Smyth, 1914; Manual for the Use of the Members of the Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, S.C., 1894; and Catalogue of Glebe Street and Central Sunday-School, Charleston, S.C., 1882. Also, the French Reformed [Huguenot] Church is within the walled city at 140 Church Street. Some French Reformed ministers written about on Presbyterians of the Past are included in the posts: David Xavier La Far (1826-1897), André Guillebeau, Jean Louis Gibert, & the New Bordeaux Huguenots, and James F. Gibert, Huguenot Presbyterian Minister. As with other cities started along bodies of water, Charleston developed from the walled city out until it covered the peninsula including land reclaimed from the Cooper and Ashley Rivers. I think a map showing the boundaries of the nine districts would have been helpful in Buildings, but in some cases information has been provided for individual districts through images of antiquarian maps.

Using Buildings can be enhanced with reference to Census of the City of Charleston, South Carolina, for the Year 1861. The census provides street names and numbers; if the structure is brick or wood; the owners of the properties; the names of residents; and some clarifying annotations. Those meandering through the city can look to Census, see who lived where, and then go to Buildings for further information. Addresses sometimes change over the years because lots are divided or condensed, also the certainty of identification is affected by the Charleston earthquake of 1886 that damaged over two-thousand buildings. Reconstruction of the city in some cases affected street addresses and lot sizes. See also the minute of May 15, 1861, page 4, Census, for other location variables. For those interested in the history of the church in Charleston some ministers of the city listed in Census are as follows:

Rev. Thomas Smyth, D.D., lived at 12 Meeting Street. He had ministered in Second Presbyterian Church since 1834.

Rev. Thomas Osborne Rice of Circular Church (Independent or Congregational) lived at 9 St. Philip Street. Thomas Smyth spoke on “The Right Hand of Fellowship” at Rice’s installation service.

Rev. Christian Hanckel resided at 173 Calhoun Street while serving the Cathedral Church of St. Luke and St. Paul (Episcopal).

Rev. William Dehon oversaw St. Philips Episcopal Church while living at 2 Hudson Street.

Rev. Paul Trapier Keith was rector of St. Michael’s Episcopal and went home to 16 Lynch Street.

Rev. George Washington Moore was leading a Methodist camp meeting near Anderson when he passed away in the pulpit, August 24, 1863. He lived at 11 Wentworth Street in Charleston and had resided in the city over forty years.

Presbyterian minister Rev. John L. Girardeau, D.D., made his home at 39 Bull Street while he pastored the Zion Presbyterian Church.

Rev. John Forrest, D.D., began ministry at First Scots Presbyterian Church in 1832 and found respite at 8 King Street. He succeeded Rev. Arthur Buist, D.D., who succeeded Rev. Aaron W. Leland. D.D.

The census was published after June 1861 and the copy used for the current article has an inscription dated November 7 of the year. One thing noticed while skimming through the text of Census are the number of vacant properties which may have been due to their occupants going to war. Fort Sumter had been fired upon in Charleston’s harbor, April 12, 1861, and in July First Manassas was fought. Other censuses of Charleston are available that date back to the 1820s.

These two books are among many that address the history of Charleston. It seems that just about any topic one can think of has been the subject of one or more books about Charleston. For example, searching the University of South Carolina Press offerings with the term Charleston brings up several varied titles. This post mentioned the Charleston Earthquake. Several years ago I enjoyed reading Richard N. Cote’s City of Heroes: The Great Charleston Earthquake of 1886, Mt. Pleasant: Corinthian Books, 2006, which provides a frightening picture of the gravity and extent of the quake while showing the comradery and mercy of Charlestonians as the result of a catastrophic event. It is hoped this post helps Charlestonianaphiles better understand some of the tools available for learning about the city as they wander its history filled streets.

Barry Waugh

The bird’s eye view of Charleston in the header is dated 1872 and from the Library of Congress.