David Wills was born in Mummasburg about five miles north-northwest of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, January 7, 1822. He received the Bachelor of Arts from Tusculum College in Greeneville, Tennessee. Tusculum was founded first as an academy in 1818 by Samuel Doak and his son Samuel Witherspoon Doak, then in 1868 it would merge with Hezekiah Balch’s Greeneville College. The eastern region of Tennessee was a New School stronghold in the decidedly Old School South (see: “What are the Old School & New School?”). Wills crossed the mountains to study for the ministry in the sandhills region of South Carolina at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary meeting in the Robert Mills designed mansion at Blanding and Pickens Streets in Columbia. He completed studies in 1850 graduating with three classmates. He was licensed that year by Cherokee Presbytery(Georgia), Old School, then the following year was ordained by South Carolina Presbytery, Old School, October 25, 1851, to pastor the church in Laurens, South Carolina. The ordination and installation commission included the stated supply to Mt. Tabor Church, E. T. Buist, who delivered the sermon from Jeremiah 3:15 emphasizing the nature of the pastoral office; Rev. John McLees of the Rock Church in Abbeville County provided an encouraging and systematic charge to Wills; and domestic missionary for presbytery, Rev. C. B. Stewart, instructed the congregation regarding their expectations for and duties to their new minister (Edgefield Advertiser, Nov. 13, 1851, p. 1). He also taught for some portion of his tenure at Laurensville (Laurens) Female College. Working with transplanted Pennsylvanian Wills on faculty was the relocated New Yorker and pastor-educator-scientist Zelotes Holmes. During his time in Laurens the church grew from 47 communicants in 1852 to 134 in 1859. Wills was dismissed to Hopewell Presbytery February 16, 1860.

David Wills was born in Mummasburg about five miles north-northwest of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, January 7, 1822. He received the Bachelor of Arts from Tusculum College in Greeneville, Tennessee. Tusculum was founded first as an academy in 1818 by Samuel Doak and his son Samuel Witherspoon Doak, then in 1868 it would merge with Hezekiah Balch’s Greeneville College. The eastern region of Tennessee was a New School stronghold in the decidedly Old School South (see: “What are the Old School & New School?”). Wills crossed the mountains to study for the ministry in the sandhills region of South Carolina at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary meeting in the Robert Mills designed mansion at Blanding and Pickens Streets in Columbia. He completed studies in 1850 graduating with three classmates. He was licensed that year by Cherokee Presbytery(Georgia), Old School, then the following year was ordained by South Carolina Presbytery, Old School, October 25, 1851, to pastor the church in Laurens, South Carolina. The ordination and installation commission included the stated supply to Mt. Tabor Church, E. T. Buist, who delivered the sermon from Jeremiah 3:15 emphasizing the nature of the pastoral office; Rev. John McLees of the Rock Church in Abbeville County provided an encouraging and systematic charge to Wills; and domestic missionary for presbytery, Rev. C. B. Stewart, instructed the congregation regarding their expectations for and duties to their new minister (Edgefield Advertiser, Nov. 13, 1851, p. 1). He also taught for some portion of his tenure at Laurensville (Laurens) Female College. Working with transplanted Pennsylvanian Wills on faculty was the relocated New Yorker and pastor-educator-scientist Zelotes Holmes. During his time in Laurens the church grew from 47 communicants in 1852 to 134 in 1859. Wills was dismissed to Hopewell Presbytery February 16, 1860.

The next call took Wills across the Savannah River to First Church, Macon, Georgia, where he would soon add to the challenges of adjusting to a new congregation concern regarding secession and the Civil War. The editor of The Macon Telegraph congratulated First Church for successfully calling Wills because he was considered in “the front rank of pulpit orators in South Carolina” (Feb. 21, 1860). The church had difficulty locating a minister after the resignation of Robert L. Breck because it had two ministers follow him combining for only three years of ministry. Wills was installed April 22, 1860. The congregation attending the installation heard a sermon from Rev. William Flinn of the church in Milledgeville (at the time the state capital), who was joined on the installation commission by the President of Oglethorpe University, Rev. Dr. Samuel K. Talmage, but the third commissioner, retired president of the University of Georgia, Dr. Alonzo Church, “was providentially detained” (Macon, April 23, 1860).

Amidst the issues the nation faced as it headed for war after Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860 and his impending inauguration March 4, 1861, Wills preached concerning “civil government a Divine ordinance, and obedience a Christian’s duty” (Macon, Jan. 26, 1861). During the war years Wills pastored his church; participated in Bible conferences and taught in retreats; prayed before government bodies as they convened; attended church judicatory meetings; preached to and prayed with Confederate troops; and visited the sick of both South and North in the hospitals and with Union prisoners of war. Looking back on the life of Wills his obituary in The Washington Post said, “He ministered impartially to the sick, wounded, and dying of the Federal and Confederate Armies” (January 1, 1916).

Macon was a strategic city because it was for much of the war the arsenal for the Confederacy, and its railroad network provided the means for distribution of arms to the troops as well as providing access to Atlanta. However, despite the city’s importance, the citizens of Macon had only limited engagements with the invading Federals including the Battle of Dunlap Hill (The Stoneman Raid), and the Battle of Walnut Creek with both engagements resulting in victory for Maconians. It is remarkable General Sherman did not attack Macon but the nearby presence of his troops affected the city. Idle soldiers find things to do while waiting for something to happen, so looting and harassment of the people of Macon occurred. One resident, John Jones Gresham, was a victim of the handiwork of idle Union soldiers when they stole his prize horse, but his forceful letter of protest to Sherman yielded return of the prize steed. When the war ended, Macon was surrendered by the mayor April 20, 1865 eleven days after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. David Wills continued his ministry through the Reconstruction years until 1870 when he left pastoral ministry to become an educator as president of an institution hopeful his influence could stabilize its program for the future.

The institution that Wills would serve had a history of setbacks caused by financial shortages, so to understand what he was getting into it is good to rehearse the school’s background. Presbyterians had learned from experience that money woes went with operating schools, but the challenges of finances did not quell their concern for education because they were concerned not only to educate ministerial candidates in general, but particularly “poor and pious youths.” In 1824 the Old School presbyteries of Hopewell and Georgia meeting in Athens organized the Georgia Education Society (GES) to “assist all indigent pious young men” in obtaining an education (Stacy, 108). Though organized by Presbyterians, the GES included members from other denominations such as Methodists and Baptists. GES’s work created the Manual Labor School (MLS) at Milledgeville, which would be similar to a vocational or trade school today. The MLS was the first step towards an educational program that would eventually include colleges providing more academically oriented curriculums for general instruction to prepare candidates for seminary. The MLS struggled to stand on its own but its shaky financial footing led to formation of a new board with twenty-four members from different denominations including Thomas Goulding as board president with its first meeting, October 21, 1835. At the time of the meeting Goulding was relocating to Columbus to become senior minister of First Church. The board met again in November 1836 hoping to continue the MLS but instead abandoned it to pursue organizing Oglethorpe University at Milledgeville with the corner stone set for the first building, March 31, 1837. Oglethorpe University opened January 1838 with 125 students, a 300-book library, and a sizeable parcel of land. The financial means for opening were pledges of 72,000.00, however indebtedness increased as it had with MLS because only 18,000.00 of the pledges were received by the end of 1839. The multi-denominational board came to an end in 1840 when the Synod of South Carolina and Georgia took control. By the time Wills comes on the scene, the war had wrecked havoc and left the university closed more than it was open during the 1860s. It had closed May 30, 1862, reopened briefly in 1866, but then closed once again three years later. The Synod did not give up hope of reopening Oglethorpe and was encouraged by the gift from the city of Atlanta of ten acres of land formerly used for fair grounds. Atlanta had recently become the state capital and the Synod saw the move as a good opportunity for the college in a larger city with better transportation. Oglethorpe was restarted with a reorganized faculty and administration that included David Wills, president; Gustavus J. Orr, professor of mathematics and astronomy; Benjamin T. Hunter, professor of physical science; and W. Le Conte Stevens, teaching chemistry and modern languages. As the curriculum was adjusted Wills became professor of belles lettres and sacred literature with R. C. Smith the chair of moral science and political economy. Other programs added were a university high school, a law department, medical program, and a commercial school (i.e., vocational school). Classes opened October 4, 1870. Things were going well for Wills and his colleagues, however as James Stacy expressed it, “But alas the sky that seemed so bright was destined soon to be obscured with clouds” (130). Money troubles once again upset the plans for Oglethorpe’s future resulting in resignations because salaries were not being paid. The board held its last meeting February 2, 1872. David Wills saw the school through settling its debts by selling the Neal House which had been purchased with funds from the fair grounds land in Atlanta and a new set of trustees were appointed by the Synod of Georgia. James Stacy concluded the chapter about Oglethorpe in History of the Presbyterian Church in Georgia hopeful of a future revival of his alma mater, to which the editor later added there was a move to revive Oglethorpe “and it has every prospect of success at this time” (141). Oglethorpe was re-opened 1911 with its president Thornwell Jacobs (served 1915-1943) and it continues today as a non-religiously affiliated liberal arts university.

David Wills next ministry involved relocation to Washington, D.C. to serve the Western Presbyterian Church within the bounds of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA). The Old and New Schools within the PCUSA had reunited in 1869. Wills transferred to the Presbytery of Washington City during its meeting May 4, 1875, with the installation service set for the following Lord’s Day. The installation commission included Rev. George O. Little propounding the questions; Rev. Dr. John Chester preaching the sermon; Rev. Mason Noble delivering the charge to the minister; and Rev. John L. French charging the congregation (The Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1875). As he began ministry in the nation’s capital Wills was confronted by a congregation that had been shepherded by three ministers in succession with each having a brief tenure and a session hopeful that his rhetorical ability would increase membership. Was he reminded of the situation when he went to First Church, Macon?

Not long after Wills began work at Western Church he did something that may provide light upon his social-political views. During the war he was faithful to his Macon congregation and remained in his pulpit. He also treated soldiers of South and North alike as he ministered to their spiritual needs, but his thinking regarding slavery, secession, and the war have not been determined. When Ulysses S. Grant ran successfully for a second term in the White House he did so with a new vice president because the first one, Schuyler Colfax, had been involved in manipulating government contracts in the Crédit Mobilier Scandal, so the second vice president was Henry Wilson. However, Wilson did not finish his term because he died of a stroke Nov. 22, 1875. Wilson was laid in state in the Capitol rotunda with the following reported by the press about a note attached to an arrangement of flowers placed on Wilson’s casket:

Floral offering from the South, by Rev. David Wills for the funeral of the lamented Vice-President Wilson the student, statesman, philanthropist, and Christian, whose name will ever live in the annals of his admiring countrymen, and whose memory will be rewarded by the wise and good without respect to section or party. (Sun, Nov. 27, 1875, p. 1)

Wilson was one of the most prominent abolitionist leaders in the nation. As a United States senator from Massachusetts (1855-1873) he consistently promoted bills and debated for the abolition of slavery before being elected the eighteenth vice president. At the time of his death, he was writing the third volume of History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America, 1872-1877. Whether Wills was hopeful that his “offering from the South” was symbolic of his own desire for a unified nation, or he was showing his former colleagues ministering in the South his long held anti-slavery view is not clear, but when the Sun was read and its message copied to other papers it must have outraged some readers that Wills presumed to speak for the South. It is not necessarily true that Wills was against slavery because Wilson was an abolitionist, but it seems that since abolition was so closely associated with Wilson it is likely Wills was making a personal statement about slavery. At the PCUS General Assembly in 1871 Wills had been in attendance during his presidency of Oglethorpe and he was nominated for moderator. When one is nominated for moderator it is usually because he is respected for faithful ministry as a teaching elder (minister) or as a ruling elder, so the Wills nomination, despite the fact he declined, shows he had some standing among presbyters at the assembly. In the end, a father of the church, William S. Plumer, was elected.

Wills was quickly put to work in the Presbytery of Washington City for his gifts and often served in commissions for ordination and installation, the organization of churches, as well as other judicatory functions including moderator of presbytery until he resigned from Western Church, January 1, 1878. During his brief call, the Western membership grew from 170 to 217 communicants. He remained without call struggling to obtain a new one with his ministry limited to both occasional and designated terms of pulpit supply. He lectured for honorariums as when he spoke about “Elements of Power” at Grove Presbyterian Church, Aberdeen, Maryland, which was followed with the additional draw that “oysters will be served” (The Aegis, Feb. 1, 1878, p. 2). There is some indication that he was suffering from a health problem that might have influenced churches to remove him from consideration for their pulpits. At the age of 56, Wills was in a difficult situation and struggling to find a consistent ministry.

At some point, Wills had made the acquaintance of Rutherford B. Hayes, which given his ministry in the Washington political community would not be surprising. Currently, the president is accessible to citizens only with a wall of security personnel watching every move, but despite the Lincoln assassination, a sitting president could be seen in church, casually on the street, or even smoking in a cigar lounge. Hayes has been described as a religious man but the specifics of his piety are elusive. The Baltimore Sun, May 14 1879, reported that President Hayes nomination of Wills to become a post chaplain for the U. S. Army had been approved by Congress. Other ministers unable to obtain church calls went into the chaplaincy such as Andrew D. Mitchell to serve in the western frontier and William T. Sprole became chaplain at West Point. But there was a significant issue faced by anyone entering the military as an officer who lived within the Confederacy, the enlistee had to swear allegiance to the United States. Earl F. Stover in Up From Handymen: The United States Army Chaplaincy, 1865-1920, comments that the traditional oath of service written in 1802 was revised in 1862 then continued in revised form until 1884 (p. 4). The purpose of the revision was to exclude commissioned enlistees from the former Confederacy; it was nicknamed “The Iron-Clad Oath.” Wills had to sign this oath by enlisting as an officer. The text of his oath is provided below. Underlines indicate blanks filled in and the line throughs are as done by Wills.

Oath of Office

One to accompany the acceptance of every commissioned officer appointed or commissioned by the President, and the oath itself to be administered to every officer mustered into the service of the United States.

I, David Wills, having been appointed a Post Chaplain in the Military Service of the United States, do solemnly swear that I have never voluntarily borne arms against the United States since I have been a citizen thereof; that I have voluntarily given no aid, countenance, counsel, or encouragement to persons engaged in armed hostility thereto; that I have neither sought, nor accepted, nor attempted to exercise the functions of any office whatever, under any authority, or pretended authority, in hostility to the United States; [that] I have not yielded a voluntary support to any pretended government, authority, power, or constitution with the United States, hostile or inimical thereto. And I do further swear that, to the best of my knowledge and ability, I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.

David Wills [signature]

Sworn to and subscribed before me at Washington D.C. this 14th day of June 1879.

V. McNally, Notary Public

Some protective plates of the Iron-Clad Oath lost their rivets and fell away as Wills’s lined out his own form, but he carefully made the point that he was a non-combatant. Stover concluded that Wills was accepted into the chaplaincy with the lineouts because his “assistance to the Rebel cause was strictly humanitarian” (4). One might think that a politically hot issue like signing the Iron Clad Oath would not be left, as in this case, to a non-military witness, a notary public; it would be expected that a military official of some rank or maybe a federal judge would oversee signing the oath. Could it be that the individuals processing oaths needed enlistees because the Indian Wars were significant in the 1870s and lineouts were winked at out of necessity? The massacre of Custer and more than 200 soldiers of the 7th Cavalry at the Little Big Horn just three years earlier likely encouraged some tenuously committed potential enlistees to stay by the home fires. Regardless of the reason, the lineouts were accepted. Wills was appointed a post chaplain and continued to serve until 1886 when he retired with the rank of Captain. His assignments included posts at Ft. McHenry; Walla Walla, Washington; Ft. Benicia, California; and McPherson Barracks, Georgia (The Washington Post, Jan. 1, 1916).

David Wills was 64 when he left the Army to return to local church ministry but this time it was in the city of Philadelphia. He accepted a call to North Tenth Street Church and was installed March 3, 1887, but it was short lived because presbytery dissolved the relationship June 4, 1888. Possibly discouraged and looking for a distraction he travelled abroad for about a year before becoming stated supply of the Leidytown Church, Chalfont, Pennsylvania, but this too was a brief call of a few years. The next opportunity would be his last pastoral call when he became the minister of Disston Memorial Church in Tacony after completing a six-month trial as supply minister. He was installed February 16, 1891. The Disston name might be recognized because Henry Disston built the Henry Disston & Sons Keystone Saw Works in Tacony. Currently an area of Philadelphia on the Delaware River, Tacony was a self-contained manufacturing community similar to a textile mill village in southern states. In South Carolina Ellison A. Smyth provided church lands and buildings within his textile mill communities. Not only was the land provided for Disston Memorial but also the building itself through funding by Mrs. Henry Disston as a memorial to her deceased daughter Mary Disston Gandy. When Henry Disston died Wills delivered a discourse from 2 Samuel 1:19, “How are the mighty fallen” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 11, 1896, p. 4). Hopefully, none of the employees crammed into Disston Memorial knew that the sermon text in its context was describing the vanity and spiritual failures of a bad king. Wills was minister for ten years beginning with his installation at the age of 69, so he was able to minister to the Tacony congregation until he was nearly 80 years of age. He was honored with the status of pastor emeritus when he retired in 1901.

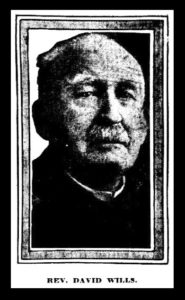

David Wills, D.D., LL. D., returned to Washington, D.C. and lived out his days with an occasional pulpit supply before passing away at the age of 93, December 30, 1915. Information about his honorary degrees is contradictory but he appears to have received the D.D. from Oglethorpe University, and the LL. D. from either Tusculum, Washington and Lee, or Washington and Jefferson College in 1888. The biography of him in the Tusculum alumni book says he “Published numerous sermons, addresses, and lectures,” but none of these could be located. He married Rebecca F. Watt of Fairfield, South Carolina, as he concluded divinity studies at Columbia Seminary in 1850. He was buried in Glenwood Cemetery January 1, 1916 after a service held at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington.

Barry Waugh

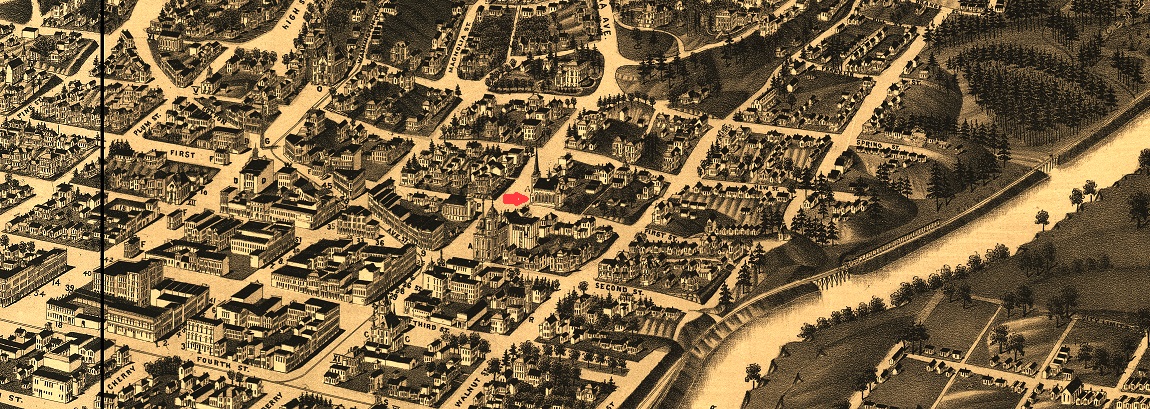

Notes—The header shows First Church, Macon, at the red arrow in the center as snipped from “Macon, Ga. County Seat of Bibb County 1887,” in the Library of Congress online map collection. A contemporary of Wills bearing the same name was an attorney in Pennsylvania who was important for establishing the Gettysburg National Military Park, so be careful that you have the right David Wills when researching. The list of ministers admitted to and dismissed from South Carolina Presbytery as found in History of the Presbytery of South Carolina, 1784-1984, by Milos Strupl, and published by the Bicentennial Task Force of the presbytery, Greenwood, 1984. Obituaries used include: The Washington Post, January 1, 1916, “Funeral of Rev. David Wills.” The blog post, “Laurensville Female College,” May 1, 2010, on the Presbyterian College website provides the history of the school on the Blue Hose Blog. Harriet Fincher Comer’s History First Presbyterian Church Macon, Georgia, 1826-1990, updated 2001, published by the church is nicely done. For the story of Oglethorpe see pages 108-41 in James Stacy’s A History of the Presbyterian Church in Georgia, [after 1912]; Stacy was a member of the Synod of Georgia and its stated clerk for 33 years, also notice that Stacy has information about the Presbytery of Florida and other presbyteries that were started within the Synod of Georgia. J. E. Nourse published The Presbytery of Washington City and the Churches Under its Care, Washington: Gibson Brothers, 1888. Transcribed text of Wills’s oath is from Up From Handymen, page 27. The Centennial of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church : Washington, D.C., 1803-1903, Washington, 1904. The Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia: A Camera and Pen Sketch of Each Presbyterian Church and Institution in the City by William Prescott White, Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott, 1895; as the title says, it includes not only churches but other buildings such as the Board of Publication. Alfred Nevin, History of the Presbytery of Philadelphia and of the Philadelphia Central, Philadelphia: W. S. Fortescue, 1888.