The Reformation in England during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547) was propagated by distribution of Martin Luther’s doctrinal and polemical pamphlets. Luther himself could be considered a publishing industry from 1517 to 1525 because his works written in Latin and/or German were dispensed abundantly all over Europe. The publications were read in Cambridge by individuals such as prior of the Austin (Augustinian) Friars, Robert Barnes, and future archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, along with Thomas Bilney, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and John Bradford. These reformers met in the White Horse Inn dining on mutton and ale as the din of Luther’s doctrine led to calling the place Little Germany. Joining these men and others for discussion was the forgotten reformer brought from obscurity by G. F. Main, Myles Coverdale.

The Reformation in England during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547) was propagated by distribution of Martin Luther’s doctrinal and polemical pamphlets. Luther himself could be considered a publishing industry from 1517 to 1525 because his works written in Latin and/or German were dispensed abundantly all over Europe. The publications were read in Cambridge by individuals such as prior of the Austin (Augustinian) Friars, Robert Barnes, and future archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, along with Thomas Bilney, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and John Bradford. These reformers met in the White Horse Inn dining on mutton and ale as the din of Luther’s doctrine led to calling the place Little Germany. Joining these men and others for discussion was the forgotten reformer brought from obscurity by G. F. Main, Myles Coverdale.

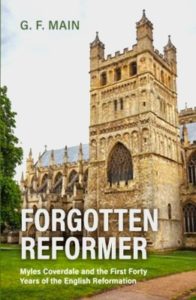

G. F. Main has a degree from Oxford and worked in education for forty-three years as a teacher and head teacher. He does not say this, but it seems researching Coverdale may have been accomplished during his summers away from the lectern. The full title of his book is Forgotten Reformer: Myles Coverdale and the First Forty Years of the English Reformation, and it is published by Reformation Heritage Books, 2023. The cloth-bound volume has twelve chapters followed by four appendices and an index combining to fill its 201 pages. The color dustjacket shows a Norman era tower of Exeter Cathedral where Coverdale was bishop, 1551-1553. The features combine to provide an attractively presented book echoing history with its medieval church.

The author informs readers that there is very little known about Coverdale’s first thirty-eight years of life. It is known that he was born in York and went to Cambridge for studies entering the Austin Friary under Barnes’s direction. Notice here that the Anglo-Saxon Augustinians of Cambridge were reading the works of Augustinian Martin Luther form Saxony. Discussions with those sympathetic to Luther’s teaching led to Coverdale’s conversion and his doctrinal transition to that of the reformers. The author makes use of published primary sources that include many of Coverdale’s writings along with translations of other reformers’ works available in two volumes from the Parker Society Series on the English Reformation, Remains of Myles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter, 1846, and Writings and Translations of Myles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter, 1844. Added to these sources are archival material held by Emmanuel College, Cambridge, as well as Lambeth Palace Library and the Bodleian, Oxford. Main includes material that may have not been awakened from its archival slumber for years.

A survey of the titles by Coverdale reflects the common subjects of the era of Henry VIII. Along with justification by faith, ending clergy celibacy (Coverdale married), the solas of the Reformation, and Henry’s great matter of divorce, it was essential for the reformers to understand the true nature of Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper because celebration of the mass and transubstantiation had come to dominate Catholicism at the expense of the ministry of the Word. Transubstantiation sees the elements of bread and wine becoming in themselves the body and blood of Christ in some sense as the doctrine developed during the resurgence of interest in Aristotelian philosophy in the Middle Ages. Coverdale had, as had his like-minded colleagues, been influenced by Luther’s consubstantiation that interprets the Lord’s presence in, under, and with the elements of the Lord’s Supper. However, with the accession of Edward VI and influences toward Reformed ideas brought to England by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer through both Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli teaching in England combined with John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger’s writings, the Reformed Lord’s Supper as a memorial meal that is a means of grace became more influential. In the mass, faith was not necessary because grace came ex opere operato within the things themselves, the bread and wine. As Coverdale worked through his understanding of the Lord’s presence in the sacrament he provided an English translation of Calvin’s A Treatise on the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, 1540 (in Writings and Translations, 422-466).

Writing and translating polemical/theological pamphlets is not the most enduring work accomplished by Coverdale because he was primarily a Bible translator. In the appendices of Main’s book he provides comparison of the English translations of the six verses of Psalm 23 in the Coverdale Bible 1535, the Great Bible 1539, the Geneva Bible 1560, and the King James Version 1611. Coverdale was involved in the first three. There is evolution and not revolution as one reads across the four versions. Main notes that some modern scholars believe Coverdale was not as capable with Greek and Hebrew as his mentor Tyndale, but even with shortcomings in the biblical languages when the King James Version as translated by pinnacles of linguistic ability is compared with his work, it stands up well. The first complete English edition of the Bible was dependent to some degree on Tyndale’s work, particularly the New Testament, with much of Coverdale’s translation using Latin and German editions of the Hebrew and Greek texts to produce the first complete Bible in the English language in 1535 (Coverdale Bible). His work on, though likely limited, the Geneva Bible became the standard version for the Puritans. With the help of those reading Forgotten Reformer, Myles Coverdale will not be forgotten again.

G. F. Main has written a book that is not only a good biography of Coverdale but also a great introductory survey of the English Reformation during the Lutheran influenced era of Henry VIII and the transition to a more Reformed theology during the brief rule of Edward VI. The book is highly recommended and Coverdale’s published works in the Parker Society Series is available on Internet Archive for reading.

Barry Waugh

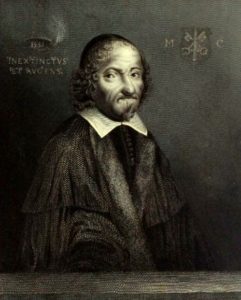

PS—There is something missing in the book, a portrait of Myles Coverdale. A search of the Internet shows there are several variations of an earlier painting said to be Coverdale and there are two stained glass windows with Coverdale, one in Exeter Cathedral, Devon, and the other in Truro Cathedral, Cornwall. Neither stained glass image is detailed and both appear to have been made much more recently than the sixteenth century. The often-duplicated image does not agree with the ones in the stained glass. In the Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900 edition) the author of the Coverdale entry, H. R. Tedder, says,

A portrait of Coverdale engraved by T. Trotter “from a drawing in the possession of Dr. Gifford,” is in Middleton’s Biographia Evangelica, vol. 2. An engraving apparently from the same portrait is prefixed to the Letters of the Martyrs (1837), and redrawn and engraved by J. Brain for Bagster & Sons, who added it to the Memorials and their reprint of the 1535 Bible; also in Mr. Dent’s Annals 1877. The authenticity is doubtful.

Tedder believes all the commonly available black and white prints come from Gifford’s drawing, which from my examination of the images is the case. The book Memorials refers to W. L. Bingley’s Memorials of the Right Reverend Father in God, Myles Coverdale,…etc., London, 1838, in which a drawing of Coverdale by J. Brain was engraved into metal for its printing. This portrait appears to be drawn from a painting in which the coat of arms of the Bishop of Exeter is included (above left shoulder) and written over the right shoulder is “1535 INEXTINCTVS ET AVOENS. Key events in 1535 include the execution of Bishop John Fisher and Sir Thomas Moore because they would not agree to the Act of Supremacy of 1534 which said Henry VIII was the head of the Church of England. I don’t know why G. F. Main did not include a portrait, but it could very well be because there is no certainty about the one currently accepted as authentic. The 1535 date seems irrelevant to Coverdale while the coat of arms is applicable.

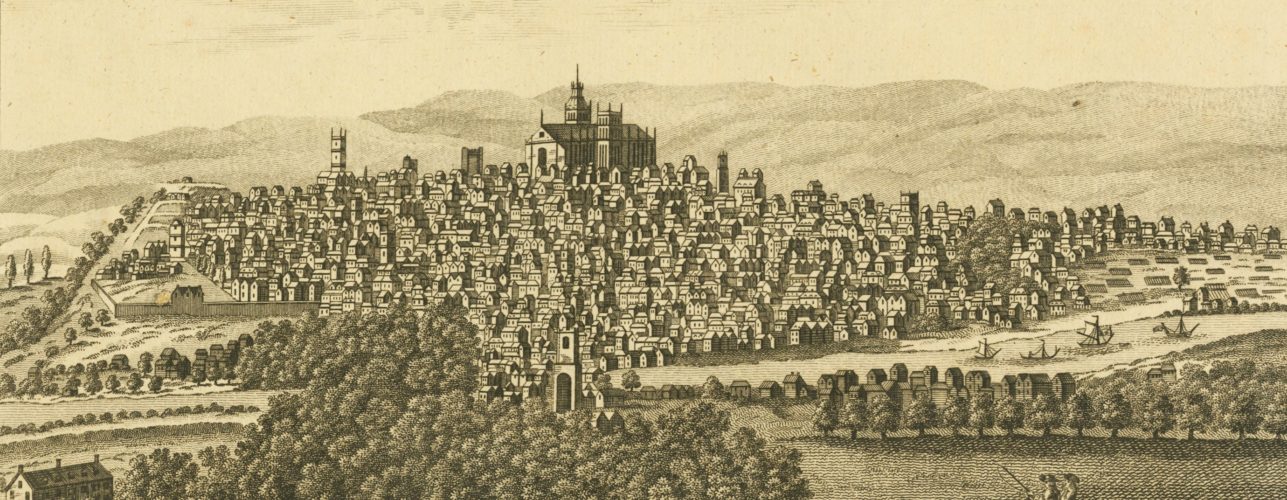

Notes—the header shows the city of Exeter with the cathedral prominent on the hill. The print description from the catalog entry for the New York Public Library digital collection is, “Perspective view of the cathedral, and city of Exeter, in the county of Devon, 1725,” and it is from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection.