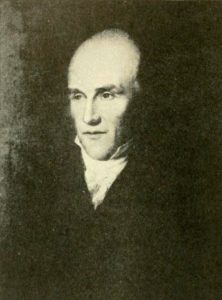

Joseph was born to Joseph and Rachel (Harker) Caldwell, April 21, 1773, in Lamington, New Jersey. His father was a physician who emigrated from Ulster in the north of Ireland; his mother’s father was a Presbyterian minister and her grandfather, surnamed Lovel, had been a Huguenot refugee from France. Joseph began practicing medicine in Lamington shortly after marrying Rachel. Two days before Joseph was born his father died from a ruptured blood vessel in his lung. The injury occurred when he overstressed himself helping some men lift a millstone. Rachel was left with little money to care for Joseph, his elder brother Samuel, and their sister.

Joseph was born to Joseph and Rachel (Harker) Caldwell, April 21, 1773, in Lamington, New Jersey. His father was a physician who emigrated from Ulster in the north of Ireland; his mother’s father was a Presbyterian minister and her grandfather, surnamed Lovel, had been a Huguenot refugee from France. Joseph began practicing medicine in Lamington shortly after marrying Rachel. Two days before Joseph was born his father died from a ruptured blood vessel in his lung. The injury occurred when he overstressed himself helping some men lift a millstone. Rachel was left with little money to care for Joseph, his elder brother Samuel, and their sister.

During Joseph’s years growing up the family moved several times because of the financial situation, which was complicated by the economic instability and variables caused by the Revolutionary War. He lived with his mother part of the time and with his Grandmother Harker at other times. After Rev. Harker died, his grandmother continued living on their farm, but Joseph’s mother moved to Amwell in New Jersey, then to Newton, and on to Trenton. The move to Trenton provided stability for the household and nine-year-old Joseph enjoyed his life along the Delaware River. He described the setting of his house as “exceedingly pleasant on elevated ground at the southern end of town” (Autobiography, 13). He remembered that during the Revolution some French troops spent a winter in the field across from his home and during the nights he could hear shouted communications among the sentinels. Joseph said of his mother and grandmother that they “were ever faithful in giving me all the instruction in their power, and especially in training me in the knowledge of God, of the scriptures” (11). The family’s next move was to Bristol on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. Joseph attended a school in town which he found particularly beneficial because of the knowledge, concern, and skill of the teacher. The teacher kindled in Caldwell an interest in mathematics that would continue throughout his life.

The next move returned the household to New Jersey where he found the best opportunities for continuing his education. Because of Joseph’s intelligence and keen interest in reading his mother managed to gather enough money to start him to the grammar school at Nassau Hall in Princeton that was overseen by John Witherspoon. But the purse strings were too tight to buy a Latin grammar book, but a fellow student gave him a torn and tattered but serviceable copy. However, continued money troubles led to relocation to Newark for a better opportunity for the family. He did not think the master of his new school, Dr. McWhorter, was as learned and capable as the master at Princeton. Joseph was an enthusiastic student that preferred studying above all else, but when the family moved once again, this time to Elizabethtown, New Jersey, his interest in education waned and he became ambivalent about learning. For about two years he stumbled along half-heartedly completing lessons until John Witherspoon came through town on his way to New York. Joseph’s mother met Dr. Witherspoon and had a conversation with him about the boy’s situation. He encouraged her to send the boy back to Princeton, but there was the reoccurring problem of money. After several months of his mother trying to resolve the funding shortage, she finally gave up and steered him towards a trade by searching for an opportunity to apprentice to a printer. However, Dr. Witherspoon was able to locate funds for Caldwell to go to Princeton for college studies.

He was fourteen years old when he arrived in Princeton in the spring of 1787. After positive results from an interview with professor Samuel S. Smith, he was disappointed to find out after further testing that he could not enter the college without remedial work. He had to successfully complete the senior class of the grammar school before beginning college studies. He protested the decision and asked for a chance to try college studies, but Professor Witherspoon did not yield. Caldwell would complete his studies in 1791 despite the added remedial work. He said in his autobiography, “As it was, I graduated under nineteen years of age. Of what importance was it to finish an education sooner?” (28). With no immediate prospects for employment, he idled his time away until becoming a teacher in a local school for a time, then he moved to Elizabethtown for a better opportunity as an assistant teacher in a larger school.

At some point during his college studies, Caldwell had come to believe he was called to the ministry. While teaching school in Elizabethtown, he pursued theological studies with the pastor of the Presbyterian Church, Rev. David Austin. A controversial man, Austin, would in a few years leave the Presbyterian Church because of his eccentric eschatological views and millennial obsessions. See the biographies of Henry Kollock and John McDowell for more about Austin. In April 1795, Caldwell became a tutor in Princeton College, and continued there for about a year. On September 22, 1796, he was licensed to preach the gospel by the Presbytery of New Brunswick.

In the summer of 1796, Caldwell’s college friend, Charles Harris, had asked him to take his position as professor of mathematics in the University of North Carolina. Harris had agreed to serve a year when the university opened in 1795. Caldwell accepted the offer and after a life marked by years of transitioning from one place to the next, he made the final move of his life when he journeyed by buggy to Chapel Hill arriving October 31, 1796. Harris and Caldwell worked together until Harris resigned in 1797 and left his friend in charge. However, it must have been a disconcerting situation for Caldwell because the school was struggling. The university lacked a definitive curriculum, needed consistent discipline of the students, lacked qualified staff, was minimally funded, and the facilities had much to be desired. The university board was charged with creating a state controlled public institution and much of the load for building the university fell to Caldwell. Starting a university was not an easy job and the early problems faced by the University of North Carolina were similar to those experienced at the University of Georgia when Moses Waddel arrived to be president thirty-four years after it opened.

Caldwell’s work in Chapel Hill continued for nearly forty years with the last years seeing decreased duties as his health declined. He was Professor of Mathematics until 1804 when he added to his duties the responsibility of the first presidency of the university. With respect to his church work, in 1810, the Presbytery of Orange overtured the Synod of North Carolina for permission to ordain Caldwell. He did not have a call, but he did supply pulpits as he could and the relationship of teacher to student could be viewed as a pastoral ministry. The synod complied and he was ordained the next year. Caldwell continued teaching, administrating, fund raising, and other duties until 1812 when he resigned the presidency to dedicate himself fully to teaching. But his successor as president, Robert Chapman, resigned after only four years, so Caldwell again served in the presidency and continued until his death.

Caldwell’s contributions to the growth and development of the University of North Carolina were many. For example, under his leadership the first educational observatory in the United States was constructed at Chapel Hill; the library increased its collection greatly; the campus grounds were expanded; and most importantly, there was financial stability. Also, the early years had been troublesome because of undisciplined and disrespectful students, and there were challenges zeroing in on the proper curriculum for a public university–but Caldwell was able to mediate solutions for these issues as well. Even though his series of articles in a newspaper calling for the construction of a railroad in North Carolina from the mountains to the coast may seem unrelated to the university, the development of railroads would provide improved accessibility to Chapel Hill and growth for the university. As W. H. Foote stated in Sketches of North Carolina, “for forty years the history of the man is the history of the University, and the history of the university is the history of the man.” (534)

Joseph Caldwell died January 27, 1835, and was buried in the cemetery on the university campus. He was married first to Susan Rowan of Fayetteville in 1804, but after just a few years she and her newborn infant died. In 1809, he married a widow named Helen Hogg Hooper. At the time of their marriage, she had three sons, but Helen and Joseph did not have any children together.

Dr. Caldwell was recognized nationwide for his educational and ministerial work. He was an active churchman participating in Orange Presbytery meetings and those of the Synod of North Carolina. He was the moderator of the synod meeting in Fayetteville in 1818. He served on committees in both judicatories. In 1816, the degree of Doctor of Divinity was conferred upon him by the College of New Jersey (Princeton), and the college’s neighbor, Princeton Seminary, gave him the opportunity to serve as a director, 1820-1829.

His publications include selected sermons issued in pamphlets, and he self-published in Philadelphia in 1822 a large set of intimidatingly titled books, A Compendious System of Elementary Geometry, in Seven Books, to Which an Eighth is Annexed, Containing Such Other Propositions as are Elementary, Among Which are a Few that are Necessary, Beyond those of the System, to the more Advanced Parts of the Mathematics. He also published in one of the Raleigh newspapers a series of articles titled “Letters of Carlton,” which were designed to awaken a desire to improve the State of North Carolina with public works projects like the railroad previously mentioned.

One final thought about Joseph Caldwell comes from a letter about him included in William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit. The letter was written by a University of North Carolina professor, Shepherd Kollock, who was the brother of pastor Henry Kollock of Independent Presbyterian Church in Savannah. The professorship which Shepherd eventually accepted had been offered by Dr. Caldwell, but he initially was inclined to refuse the opportunity. The following is what Shepherd Kollock said in recounting his conversation with Caldwell about the teaching position.

I frankly told him that, at first view, I was disinclined to do so; not merely on account of my youth and inexperience, but also because my preferences were for the pastoral office, and because I was licensed to preach. He, at once, replied, “That is what we want—more preaching on the Sabbath and in the week; and if a small congregation in the country be united to the college pulpit, you may, with a good conscience, secure the end of your education and licensure.” He then proceeded to speak for some time on the absolute necessity of religion in the government of a college, observing that, without such influence, literary institutions must sooner or later become the fountains of corruption; that nothing so effectually as this imposes a check upon youthful folly and wickedness; that without religious principles, no system of discipline, however wisely formed, or faithfully executed, can save an institution from moral deterioration, or prevent the highest talents or the richest attainments from being perverted to the worst of purposes—every seat of science should therefore be the seat of Christian piety. These remarks, coming from one who had been more than twenty years connected with a college, made an impression on me that was never lost. One of the trustees informed me that about a week after this, Dr. Caldwell addressed the Board on this subject, and spoke an hour, in a manner most convincing and persuasive. He concluded his address in this manner—”Let the Gospel be fully preached at your seat of learning, by any faithful minister of any denomination—I will add, even ‘through strife and envy,’ and, like the great Apostle, ‘I will rejoice.’” After the professorship was established, I accepted the office—influenced chiefly by his arguments, and entered upon my duties—I gave instruction in rhetoric and logic, and devoted much of my time to the appropriate work of a minister.

Things have changed over the course of the past two centuries.

Barry Waugh

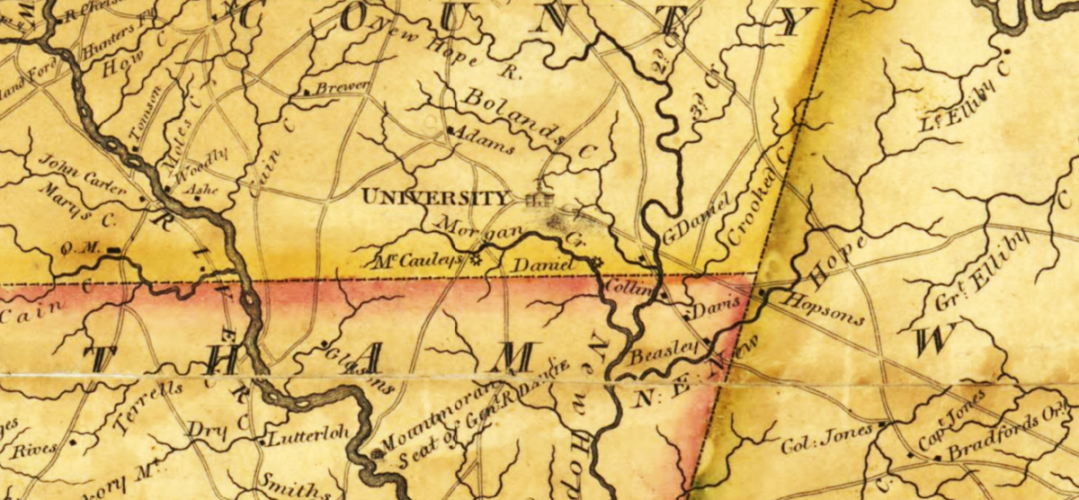

Sources—The header is a section from the map in the Library of Congress digital collection: “To David Stone and Peter Brown, Esq.: this first actual survey of the state of North Carolina taken by the subscribers is respectfully dedicated,” Philadelphia : Printed by C.P. Harrison, 1808. A small drawing of the original University of North Carolina building is just to the right of the word “UNIVERSITY” at the center of the map. Raleigh is to the right of the university and Salisbury to the left. Autobiography and Biography of Rev. Joseph Caldwell, D.D., LL.D., First President of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: John R. Neatherly Printer, 1860. W. H. Foote, Sketches of North Carolina, Historical and Biographical, New York: Robert Carter, 1846, chapter 36, “University of North Carolina and the Rev. Joseph Caldwell, D.D.,” pages 527-57. W. B. Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit, Vol. 4, New York: Robert Carter, 1858. Princetonians, 1791-1794, A Biographical Dictionary, J. Jefferson Looney and Ruth L. Woodward, 1991. Minutes of both Orange Presbytery and the Synod of North Carolina of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA).