Read footnote 1 at the end of the title before reading the article.

{3}

J. Gresham Machen & LeRoy Gresham: Cousins, Confidants, & Churchmen[1]

by Barry Waugh

Mary and John Jones Gresham had two children that survived to marry and have families, Mary Jones and Thomas Baxter. Mary Jones, who was also called Minnie, would live in Baltimore with her husband Arthur Webster Machen and they would enjoy the births of three sons, one of which was born in 1881 and named John Gresham Machen. At the time of his birth, Thomas and his wife Tallulah had been raising their son LeRoy in Madison, Georgia, since his birth September 21, 1871. When Thomas and Lula Gresham moved their family to Baltimore their residence was close to that of the Machens. Gresham and Loy, which was the name Machen most often used for his cousin, became more and more like brothers than just first cousins because of their many opportunities to socialize, share common interests, and experiences. The ten-year age difference between the boys put Loy in the position of being like an older brother to J. Gresham Machen.

Mary and John Jones Gresham had two children that survived to marry and have families, Mary Jones and Thomas Baxter. Mary Jones, who was also called Minnie, would live in Baltimore with her husband Arthur Webster Machen and they would enjoy the births of three sons, one of which was born in 1881 and named John Gresham Machen. At the time of his birth, Thomas and his wife Tallulah had been raising their son LeRoy in Madison, Georgia, since his birth September 21, 1871. When Thomas and Lula Gresham moved their family to Baltimore their residence was close to that of the Machens. Gresham and Loy, which was the name Machen most often used for his cousin, became more and more like brothers than just first cousins because of their many opportunities to socialize, share common interests, and experiences. The ten-year age difference between the boys put Loy in the position of being like an older brother to J. Gresham Machen.

The purpose of this article is to consider the relationship of J. Gresham Machen and LeRoy Gresham following their years growing up together in Baltimore. This will be accomplished using a selection of letters written between April 1921 and April 1935. The letters will show that the two cousins continued to be both friends and confidants regarding issues of common interest including the situation with the Presbyterians as it developed in the 1920s in both the PCUSA and the PCUS.

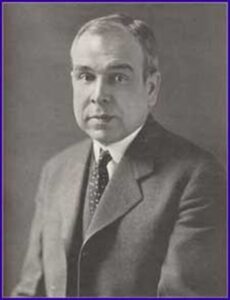

LeRoy Gresham

LeRoy Gresham’s education included study in Lawrenceville Academy in New Jersey before he travelled the few miles down the road to Princeton University to earn both a B.A. and a M.A. Returning to Baltimore, Loy studied for one year at Johns Hopkins University and then went to the University of Maryland for his legal studies earning the LL.D. Initially, he followed in his father’s footsteps by practicing law in Baltimore beginning in 1896 but then after six years of work he realized that God was calling him to the pastoral ministry. Loy was just over thirty years of age when he began seminary studies. Unlike Machen’s choice for seminary, Loy selected Union Theological Seminary, Virginia, where he earned the B.D. {4} in 1906. He was licensed that May by Potomac Presbytery of the PCUS, and then he was ordained by Orange Presbytery in November of the same year. Rev. Gresham’s first call was a brief one of three years to a church in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His next call would be his last because he would serve the church in Salem, Virginia, beginning in 1909 and remain there until his retirement in 1946. LeRoy was honored with the DD by both King College in Bristol and Washington and Lee in Lexington, Virginia. Loy had married Jessie Rhett in 1903, and they had two sons, Francis, who was the youngest, and Thomas Baxter.

LeRoy Gresham’s education included study in Lawrenceville Academy in New Jersey before he travelled the few miles down the road to Princeton University to earn both a B.A. and a M.A. Returning to Baltimore, Loy studied for one year at Johns Hopkins University and then went to the University of Maryland for his legal studies earning the LL.D. Initially, he followed in his father’s footsteps by practicing law in Baltimore beginning in 1896 but then after six years of work he realized that God was calling him to the pastoral ministry. Loy was just over thirty years of age when he began seminary studies. Unlike Machen’s choice for seminary, Loy selected Union Theological Seminary, Virginia, where he earned the B.D. {4} in 1906. He was licensed that May by Potomac Presbytery of the PCUS, and then he was ordained by Orange Presbytery in November of the same year. Rev. Gresham’s first call was a brief one of three years to a church in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His next call would be his last because he would serve the church in Salem, Virginia, beginning in 1909 and remain there until his retirement in 1946. LeRoy was honored with the DD by both King College in Bristol and Washington and Lee in Lexington, Virginia. Loy had married Jessie Rhett in 1903, and they had two sons, Francis, who was the youngest, and Thomas Baxter.

Machen Recommends LeRoy for a New Call and Preaches at Hollins College[2]

At one point in LeRoy Gresham’s ministry in Salem, Machen mentioned Loy in a letter to Rev. Stuart “Bill” Hutchison as a possible candidate for his soon to be vacant pulpit with the hopes that he would recommend Loy to the pulpit committee. The opportunity that Machen believed could be a suitable change for Loy was just across the state in the First Presbyterian Church of Norfolk. Bill Hutchison had been the minister of the PCUS church for about ten years, and his new call was to the East Liberty Church, PCUSA in Pittsburgh. If Loy was to move to Norfolk, the change would take him from a congregation of over three-hundred members to one of nearly a thousand. Dr. Machen believed that the Norfolk pulpit would be a good fit for Cousin Loy, so he presented his case to Bill regarding his qualifications.

I have come frequently into contact with his work at Salem, and every contact with it has been an inspiration and a benediction. Though on a smaller scale, it is more like your work at Norfolk than almost anything else I have seen. That is to say, it is the work of a genuine minister of the gospel, who is in full possession of the necessary intellectual and other gifts. I do not believe that a more absolutely unselfish, consecrated man ever entered the ministry than my cousin. To win one soul he will pour forth unstintedly all the treasures of mind and heart that God has given him. And that kind of painstaking work has produced a congregation which it is a joy to see.

Machen went on to comment to Bill that the Salem congregation believed Loy was content with his call and would not leave the church for any reason. He added that Loy believed “his great duty is to his own congregation, and that, especially since his work there is so highly blessed of God, he has absolutely no time to spend upon any attempt to seek a larger field.” Despite the confidence of the congregation regarding Loy’s happiness as their pastor, Machen thought there was a possibility his cousin would leave Salem for another call when he believed God was calling him to do so. He commented, “I am sure that Loy will not decline the real call when it comes.” The letter shows Machen’s exuberance as he spoke up for his cousin because he wanted the best for him, and it looked like First Presbyterian Church in Norfolk was a call suited for his gifts.

As the letter draws to its close, Machen mentioned that it was his hope to have a week of hiking in the Natural Bridge area of Virginia with Loy before he preached the baccalaureate sermon at Hollins College for Women in Roanoke the evening of Sunday, June 5. Though the {5} sermon is untitled, Machen’s text was 2 Corinthians 4:18, “While we look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen: for the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal.” According to the summary by the writer for Hollins Magazine, Machen’s emphasis was on the need for a deep faith that provides a solid and long-lasting foundation for Christian living. Machen also referred to the familiar text from Matthew 6:33, “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you.” He encouraged the new graduates to pursue the Kingdom first and establish a sure foundation for practical Christianity. Hollins Magazine commented further.

Mr. Machen’s words served as a reminder to us that although we may aspire to be of much practical service to the world, our deeds will be futile unless they have beneath them a deep spiritual raison d’ếtre. We need first of all to be sincere believers in Christianity, and “it will follow as the night follows day” that our words and actions will have an unfailing power for good in the world.[3]

The baccalaureate sermon presented the simple message that Machen so often emphasized—the practical aspects of Christianity must be built upon a solid foundation of doctrine, which in this case he corresponded with seeking first the Kingdom of God. If the practical is sought without first having a solid foundation, then only a superficial and self-serving obedience will follow.

Christianity and Liberalism, New Testament Greek for Beginners, and the PCUS[4]

The year 1923 was a particularly important one for Machen’s academic career because two of what would become best-selling books, Christianity and Liberalism, and shortly thereafter, New Testament Greek for Beginners were published.[5] In a letter of May 2, 1923, Loy thanked Gresham for the recently received copy of his just released Greek grammar about which he observed, “it looks like an excellent little book” and “the preface is most interesting,” but he did not think he could assess it thoroughly until he had the opportunity to use it, hopefully, with his youngest son, Francis. Little did Loy or Machen know that the Greek textbook would be long appreciated and esteemed after their time. It remained in print with Macmillan for years, after which it was published by other companies with an updated edition in 2003.

Loy mentioned that he had “one or two interesting side-lights” on Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism. The local newspaper, Roanoke World-News, had published in its literary column a review of the book written by a member of Loy’s congregation whom he identified as Dr. Painter. Loy said the man was a former Lutheran minister, who was a widely read man, had a keen sense of humor, and was “altogether a most agreeable man personally.” But Loy speculated that the reason Dr. Painter was no longer a minister was because he fell out with the Lutherans, which Loy believed was due to his being “the only man in the ministry that I ever heard of that was president of a cigarette-machine company; and I am inclined to think that his business had something to do with his not getting along with the Lutherans.”

Dr. Painter was retired Professor of Modern Languages and Literature F. V. N. Painter of Roanoke College.[6] He was an accomplished scholar having written a number of books including A History of English Literature, Introduction to English {6} Literature, Introduction to American Literature, and several others. He was ordained into the Lutheran ministry and began teaching in 1878. In order to have more time for writing, and apparently as Loy mentioned, to try his hand at manufacturing by becoming president of the Bonsack Company, he retired from the college in 1906. The Bonsack Company had been founded by James Bonsack to manufacture the cigarette-rolling machine he had patented.[7]

Painter’s two-book review is titled, “Orthodoxy and Modernism,” with Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism representing orthodoxy and Percy Stickney Grant’s The Religion of Main Street representing the modernist perspective.[8] The review provides a brief account of Machen’s chief points as contrasted with those of Grant’s book. Machen is described as one of the “stand-patters,” while Grant is presented as a member of the “radicals.” Machen’s teaching regarding the plenary inspiration of Scripture, doctrines such as original sin, the deity of Christ, the virgin birth, and substitutionary atonement were not in accord with the modern, progressive, and liberal needs of the era. Grant’s progressive and liberal views are said to fit the needs of the scientific age and he believed traditional, creedal doctrine to be “archaic if not false.” Grant commented further that “‘in Adam’s fall we sinned all’ was the old theology” and its associated emphasis on sin “crushed humanity.” Painter ended his nine-hundred-word review saying, “After carefully reading these two theological polemics, this reviewer turned with relief and refreshment to the 13th chapter of 1 Corinthians, in which Paul touched the stars, “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.”

As a promoter of Machen’s work, Loy was crafty in his method. While a woman Bible teacher from Union Seminary Training School in Richmond was participating in the Presbyterial Auxiliary meeting, she visited the Greshams and found a copy of Christianity and Liberalism strategically placed in the house for her sure sighting. She picked up what Loy described as “bait” and commented that she was delighted with the book. Loy responded by giving her one of his extra copies, thanked her for her interest, and encouraged her to continue reading his cousin’s work.

Machen responded to Loy’s letter within a few days and after informing him that he would be too busy to visit Salem until the next year, he encouraged Loy regarding his selection to attend the PCUS General Assembly for his presbytery, but he also expressed concern about what he saw as troubling signs in the PCUS. Machen told his cousin that the “Southern Church puzzles and disturbs me.” In particular, he had noticed recently that Dr. Leighton Stewart, whom he described as “a liberal propagandist in China,” had recently been examined extensively and admitted into the Presbytery of East Hanover in Richmond. He also found unsettling the collective review of books in the spring issue of The Union Seminary Review that included Harry Emerson Fosdick’s, Christianity and Progress, 1922, and Charles A. Ellwood’s, The Reconstruction of Religion: A Sociological View, 1922.[9] The reviewer, John Calvin Siler, a Union alumnus and a pastor in Shenandoah Junction, West Virginia, concluded the review saying, “We must read these books not as theological treatises, but as books on practical religion. These books have no special message on doctrine, but they have a burning message on practice.” The separation of doctrine from practice was one of Machen’s chief concerns with the PCUSA, and seeing the same thinking in the denomination of his youth bothered him greatly. He added, “It looks to me sometimes as though the Southern Church were going to give Christianity up without even being conscious that anything particularly worth while is being lost.” However, he believed there were some “splendid men” who were concerned about the issues taking place in the PCUS such as R.C. Reed of Columbia Seminary.

Machen’s perspective on the situation in the PCUS could have been encouraged by an article in the January 1923 issue of The Union Seminary Review, which is the issue that preceded the one in which he found the objectionable review mentioned to Loy. The opening article, “What is Modernism?,” was by John M. Wells, who at the time was the president of Columbia Theological Seminary.[10] Wells presented the answer to his question with seven points. First, as to God, Modernism is Pantheism; second, as to the Bible, it is higher criticism; {7} third, as to Christ, it is Unitarianism; fourth, as to salvation, it is Socinianism; fifth, as to the Church, it is Latitudinarianism; sixth, as to sociology, it is Bolshevism; and seventh, as to method, it is evolutionism. Machen might also have been heartened that Wells quoted from his discourse titled, “Liberalism or Christianity,” published in The Princeton Theological Review.[11] There is no doubt what Wells thought about modernism as he composed his conclusion.

I have no hesitation in saying that the thing called Modernism is the greatest danger that menaces the world today…. They take from us our personal God; they destroy our Bible, they strip us of our Divine Christ; they would destroy the only sure way of Salvation, through faith in a crucified Saviour; they reject our God given Church; they ruin our social fabric, builded on home, Church, and State; and would put atheistic evolution in the place of God’s hands. May God Almighty deliver us from the curse of Modernism.[12]

The assorted book reviews in this same issue of the Union Seminary journal included several books many of which were aimed at a popular audience such as—Real Religion, by Gipsy Smith; Spiritual Energies in Daily Life, by Rufus M. Jones; books published by the YMCA; Happiness and Goodwill, and Other Essays in Christian Living, by J. W. MacMillan; and How to Make the Church Go, by W.H. Leach. The positive reviews of the Fosdick and Ellwood books noted by Machen may have been the editorial policy of the seminary journal as it was appealing to a broader readership.

LeRoy’s Thoughts on Machen vs. Charles P. Fagnani of Union Seminary, New York[13]

In the April 1924 issue of The Survey an article answering the question, “Does Fundamentalism Obstruct Social Progress?” was published. [14] Professor of Old Testament Literature and Exegesis Charles P. Fagnani of Union Seminary, New York, presented the affirmative view, while the negative view was crafted by J. Gresham Machen. Fagnani described a fundamentalist as one who believed the teaching of “men long dead” as authoritative regarding “religion, science, and history.” He added that those men were primitive, pre-scientific, and most of what they knew was incorrect; the fundamentalist is unwilling to examine critically the views of those men long dead. The “tap-root doctrine from which all other beliefs proceed,” said Fagnani, is the fundamentalist’s belief in the infallibility and inerrancy of Scripture based upon an appeal to original autographs. Then Fagnani mentioned several versions of the Bible and how their translations of the same passages varied. He was particularly at odds with the fundamentalists’ insistence that in Isaiah 7:14, Immanuel must be born of a virgin. He added that the “fundamentalist therefore makes the serious mistake of supposing that in any given case he has an oracle from God, in the present tense, valid for all time, addressed to himself personally.” The professor commented further that the revelation of God’s will could not have come to an end two thousand years ago as a “deposit of faith” in the covers of an ancient book, and all the ideas of the Jews and early Christians expressed in “these imperfect translations of imperfect original texts” are literally and inerrantly true. The fundamentalists were unwilling to accept anything new, opposed explaining miracles scientifically, and wrapped up in a “theological or ecclesiastical faith.” He summed up his perspective on fundamentalism and social progress saying, “The modernist faces forward, the fundamentalist, backward,” and the formative principles of fundamentalism are “the literal, uncritical belief in the inerrancy of the ancient literature contained in the Bible and unquestioning acceptance of the traditional doctrines and creeds supposed to be founded upon it.” So, Fagnani answered “yes” to the question, “Does Fundamentalism Obstruct Social Progress?,” because a view that looks backward could not deal with the problems of the present and future.

Machen began his case supporting his belief that fundamentalism does not inhibit social progress by clarifying the meaning of fundamentalism. He observed that Fagnani included all those who believed in supernatural Christianity as proponents of fundamentalism, but Machen limited fundamentalism to those {8} within the greater body of historical-supernatural believing Christians that were premillennialists. As he responded to Fagnani, Machen made four points. In the first, he contended that fundamentalists are not against new information and discoveries from science, but do in fact welcome them. However, he added, using the resurrection as an example, the new information must be tested by the historic and foundational facts about the resurrection found in Scripture; if the new findings of science and history contradict the resurrection, then they must be abandoned. Secondly, Machen pointed out that modernism accuses fundamentalism of inhibiting social progress because of its pessimistic view of man. What is described as pessimism by modernists is foundational to Christianity because it, says Machen, “begins with the consciousness of sin, and grounds its hope only in the regenerating power of the Spirit of God.” Without an understanding of the doctrine of sin, any ideas about man and his welfare are necessarily deficient. In the third place, he said, “historic Christianity is thought to be inimical to social progress because it is individual rather than social.” This objection, said Machen, is based on a caricature of the Christian religion, because in fact, Christianity is “social as well as individual,” because it is concerned not only with one’s relationship to God but also to his fellow man, but he added that there is some truth in the statement that historic Christianity is individualistic. Christians, he added, should be concerned about how civil government inhibits the freedom of the individual by using law to bring about social conformity and public welfare. Machen commented, “The rapidly progressing loss of liberty is one of the most striking phenomena of recent years.”[15] The fourth objection to historic Christianity addressed was, “it is doctrinal rather than practical.” He contended that the two—doctrine and practice—are not mutually exclusive and “the Church … ought to do both.” The aversion to doctrine in that day, said Machen, was symptomatic of a general intellectual and spiritual decline. As his article drew to its conclusion, he summed up his response to the four objections, “We are opposed with all our might to the passionate anti-intellectualism of the modernist Church; we refuse to separate religion sharply from science; and we believe that our religion is founded not upon aspirations but upon facts.” Dr. Machen ended his defense of the fundamentalist view by pointing out the growing decadence of his day while calling for “a mighty revival of the Christian religion which like the Reformation of the sixteenth century would bring light and liberty to mankind.”

Loy concluded his letter with his perspective on Fagnani’s contribution which he described as “a subtle piece of misrepresentation.” He added that some on the conservative side would fit the description given by Fagnani but not all fundamentalists are “obscurantist and reactionary.” In contrast with Fagnani’s caricature of fundamentalism, Loy told Machen that his contribution was “a very fine piece of work—allowing for the limits of space, about as good as anything we have had from you.” The last lines tell of items of family interest such as Loy and Francis’s hiking and then climbing Thunder Hill from Parker’s Gap. They thoroughly enjoyed the outing but the panorama they expected to see from the peak of the hill was obscured by the forest. Some of Machen and Loy’s common interests included walking, hiking, climbing, and enjoying creation.

Henry van Dyke, Princeton’s First Church, and On the Separateness of the Church[16]

In the late spring of 1924, Machen’s brief ministry as stated supply for the First Presbyterian Church in Princeton ended. The difficulty of preparing two sermons each week, as well as the increasing opposition to his pulpit ministry spearheaded by Dr. Henry van Dyke had taken a toll. Van Dyke’s opposition to Machen had climaxed in a letter of Dec. 31, 1923 which he sent to both the church session and a local newspaper. He did not mince words when he said what he thought of Machen’s preaching on the recent Sabbath—he described it as “bitter, schismatic, and unscriptural preaching” and that it was a waste of his limited opportunities to have time with his family to listen to such a “dismal, bilious travesty of the gospel.”[17] Van Dyke let it be known that he was giving up his pew in First Church. He was the talk of the press even making the pages of Time magazine for January 14, 1924 in an article titled, “Van {9} Dyke’s Pew.”[18] The sermon that angered him so much was “The Present Issue in the Church,” which became as important for fundamentalists as Harry Emerson Fosdick’s modernist discourse, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”[19] The problems in First Church combined with the success of Christianity and Liberalism—the sales of which were enhanced by the attention brought to Machen by van Dyke’s outrage—weighed heavily upon Machen. Added to his troubles was the release of The Auburn Affirmation that same January and the increase of its signatories from 150 to over 1200 by May. By the time of Loy’s letter to Machen of April 9 the following year, there were not enough hours in the day for his cousin to accomplish his work.[20]

In January 1925, Loy had invited Gresham to Salem for a family visit that would include opportunities for him to preach in First Church, Salem, and First Church, Roanoke. Many throughout the country were seeking Machen as a guest preacher, but cousin Loy hoped he would come to Salem for a family visit and through his preaching expose the PCUS to the issues he was raising in the PCUSA. Loy added that he fully realized it was going to be more difficult for his cousin to get away from Princeton, but he hoped that he could make the trip because Dr. Young, the pastor of the Roanoke congregation, was greatly interested in having him preach to his flock and Loy wanted him to minister the Word in Salem while enjoying the hospitality of the Gresham home.[21]

Ever in a mode of encouragement, Loy thanked his cousin for the copy of his “fine sermon,” On the Separateness of the Church, which he described as “mighty good stuff.” He was particularly impressed by the paragraph concerned with the 1100 years between Augustine and Luther, which were described as “one of the most inspiring and heartening things I have read in a long time.” He also expressed admiration for Machen and his tenacity in the face of opposition commenting that it “takes a real man to do it, and a real Christian.” Loy described the modernists as having talented speakers that included “some of the smoothest camoufleurs among them that the world has ever seen … [and] they would deceive the very elect.” Loy related to Machen that he had heard Shailer Matthews deliver lectures at Hollins College, which is the same college where Machen delivered the baccalaureate sermon in 1921. Matthews, according to Loy, spoke on ethics and avoided controversial comments while speaking with a pleasing style similar to that of Harry Emerson Fosdick. However, he added that for Matthews, “there is no such thing as truth—everything is stated in terms of values. As nearly as I can make him out, he is a sort of Ritschlian pragmatist, and powerful close to an agnostic. According to him, every man is his own Bible.”

Machen did not let any time slip by when he received Loy’s letter because he answered it on April 16. Loy’s encouragement regarding The Spirituality of the Church and his comments concerning the slipperiness and speaking skills of the modernists prompted Machen’s response.

I cannot begin to tell you how grateful I am for your letter of April 9th. Your approval and sympathy goes straight to my heart, and they have been the more needed because of what I have just passed through. For ten days prior to the meeting of our Presbytery on April 14th, I was laboring day and night in an effort to carry the Presbytery for the conservative position. It was, I think, almost the most trying time of my whole life. I was getting about three hours of sleep per night, and was laboring harder than I have for many years.

Loy’s encouraging words bolstered his cousin in the face of difficulty, but the results of the presbytery meeting were not as encouraging for Machen as they could have been. He told Loy that Dr. Charles Eerdman had been elected a commissioner to the General Assembly by a narrow margin and of the eight commissioners elected to attend General Assembly; five would oppose his candidacy for moderator. However, Eerdman went on to be elected the moderator by a majority who hoped he would “Drive out Ecclesiastical Bolshevism.”[22]

Loy’s Sympathy for Machen’s Plight and a Family Tragedy[23]

Ten years passed after the April 1925 correspondence between Loy and Machen. Several letters had been exchanged; Machen’s situation with the PCUSA had deteriorated severely; he left Princeton Seminary with {10} other faculty in 1929 to establish Westminster Theological Seminary; and he would soon be tried and suspended from the ministry, lose his appeal, and go on to be a founder in June 1936 of a new denomination that would become the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. It had been a complex, hostile, and discouraging decade for Machen with respect to Princeton and the denomination, but he had found new hope for Presbyterians in his work with Westminster Seminary and would soon add the pleasure of organizing a new church.

Loy’s letter of April 2, 1935 to his cousin expressed his support for him in his testing times and his own personal outrage at the way the modernists had made their case against him. He described the action of the General Assembly as “an unqualified outrage—unconstitutional, ultra vires, un-Presbyterian, and altogether prompted by a spirit of narrow-mindedness and intolerance.” Loy believed the outcome of the case was assured from the beginning and “the cards were stacked against you.” But he also related the comments of Moderator of New York Presbytery Russell that the actions against Machen had backfired to a degree because the way he had been treated did not look good to the general public. Loy added that lots “of men who are not on your side will see that the boot has been shifted to the other foot, and that the very ones who have been raising the cry of intolerance have been guilty of that unpardonable sin themselves” to which he added that he could not “help feeling that this adverse decision is really in your favor and that it will lead to vindication in the end.” The General Assembly of 1935 would meet in May and suspend Machen from the ministry for his involvement in the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions. Loy concluded his letter with comments about the family and news about the Salem Church which would have nineteen young people received on profession of faith during the spring communion “without any evangelistic meeting or other special effort—only the usual communicants class.”

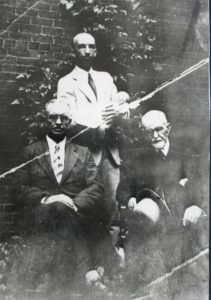

Just two weeks after Loy sent his letter of support and encouragement to Machen, he was writing to Machen’s brother, Arthur, about a great family tragedy.[24] He said that he had “been waiting to communicate with you further in the hope that Francis’s body might be found.” Loy and Jessie’s youngest son had drowned. He had recently moved to Minnesota where he had been with friends at Lake Harriet in Minneapolis, and as the group strolled along the shore he was telling them he could swim across the lake. At first, none of them took him seriously. However, he was serious, so he borrowed a swimsuit from his friend Gordon Dhein and took out across the lake. One of his friends thought he might turn back due to the coldness of the water. Francis continued towards the opposite shore but disappeared beneath the surface after having gone about 150 yards. Loy went on to say that his eldest son, Tom, who went to the scene of the drowning, said “that all effort to find his body by dragging have failed, and that they will probably have to wait until it rises in the usual way.” Loy commented, “Of course what happened was that he was seized with cramps in the cold water and went down like a shot.” Francis had not been married very long, he was survived by his wife, Mitzi, and their infant son, LeRoy Gresham, II, named for his grandfather, and the whole family was in mourning.[25]

Just two weeks after Loy sent his letter of support and encouragement to Machen, he was writing to Machen’s brother, Arthur, about a great family tragedy.[24] He said that he had “been waiting to communicate with you further in the hope that Francis’s body might be found.” Loy and Jessie’s youngest son had drowned. He had recently moved to Minnesota where he had been with friends at Lake Harriet in Minneapolis, and as the group strolled along the shore he was telling them he could swim across the lake. At first, none of them took him seriously. However, he was serious, so he borrowed a swimsuit from his friend Gordon Dhein and took out across the lake. One of his friends thought he might turn back due to the coldness of the water. Francis continued towards the opposite shore but disappeared beneath the surface after having gone about 150 yards. Loy went on to say that his eldest son, Tom, who went to the scene of the drowning, said “that all effort to find his body by dragging have failed, and that they will probably have to wait until it rises in the usual way.” Loy commented, “Of course what happened was that he was seized with cramps in the cold water and went down like a shot.” Francis had not been married very long, he was survived by his wife, Mitzi, and their infant son, LeRoy Gresham, II, named for his grandfather, and the whole family was in mourning.[25]

Machen opened his June 4, 1935 letter, “Just when I was intending to answer your letter of April 2nd, your great sorrow came, and of course all I could do was to send you a word—a very poor and feeble word, it is true—by way of sympathy.”[26] He then thanked Loy for his recent letter which “did good to his inmost soul” and Loy’s indignation with regard to Machen’s trial by the PCUSA was “balm to a wounded spirit.” He was particularly grateful to Loy for his continued support over the years and the knowledge that he really understood the issues involved in the controversy in the church. After describing the General Assembly of 1935 as even more ruthless than that of the previous year, he told about the Blackstone-Kauffroth case.[27] The two were graduates of Westminster Seminary whose examinations before Chester Presbytery had been satisfactory and they had affirmed all the constitutional questions. However, they would not affirm support of the official boards of the denomination, and they would not promise not to support the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions. A minority in Presbytery filed a complaint, the Synod sustained the complaint, but the General Assembly through its Permanent Judicial Commission ruled against the complaint reasoning that a minority has no right to compel a majority in a presbytery to add anything to the constitutionally defined examinations for licensure or ordination. Machen believed, though, that it would be a short-lived victory because the decision would likely be ignored. {11}

Conclusion

Less than two years after the last letter used for this article, J. Gresham Machen would die of pneumonia in Bismarck, North Dakota. As the years had passed from the letter to Bill Hutchison in 1921, Gresham and Loy had continued to enjoy their kinship as cousins, encouragement as confidants, and both the pleasures and troubles facing them as churchmen. Both men grew up in Baltimore, were benefitted by having Christian and Presbyterian parents, were educated in the best schools, and went on to enjoy their callings as ministers. However, there were differences—Machen chose the PCUSA, while Loy stayed in the PCUS of his youth; Machen entered educational work at Princeton Theological Seminary, while Loy instead became a church pastor; Machen was not married, while Loy was married to Jessie and they had two children; and Machen was in the public eye, though reluctantly, while Loy seemed to like his privacy and a simpler life as a small-town pastor of a fairly large church. The two cousins encouraged each other through the difficult times and when Machen found himself with fewer and fewer friends in his later years, he always had friends in his family, especially his like-a-brother cousin, Loy.

Notes

[1] The article was originally published in The Confessional Presbyterian, vol. 10, pages 3-11, 2014. The author is grateful to editor Chris Coldwell and Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary for its use on this site since the issue is out of print. The text here is the same as in the journal but photographs used in the original have not been included, and a few footnotes were deleted and others edited. All of the letters cited in this article, unless noted otherwise, were provided by Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, from the J. Gresham Machen Collection. Archivist Karla Grafton was very helpful locating and providing materials. There are some numbers in bold print in { } indicating the beginning of the page in the original. You may want to read on this site “LeRoy Gresham, 1871-1955” and the five part series that begins with “J. Gresham Machen, France 1918.” Also, the article “John J. Gresham & J. Gresham Machen’s Georgia Ancestry” is about Loy and Machen’s grandparents. The header shows the John Jones Gresham home in Macon, Georgia, which is currently a boutique bed &breakfast named for its year of completion “1842 Inn.” The picture of four generations of Greshams was taken just before Francis, holding his son, drowned. Thomas is holding his hat. Does he resemble Sigmund Freud?

[2] Citations in this section are from, J. G. Machen to Bill Hutchison, April 29, 1921.

[3] “The Baccalaureate Sermon,” Hollins Magazine, June 1921, 494–95; The letter from the president of Hollins College to J. G Machen, March 3, 1921.

[4] Unless noted otherwise in this section citations are from, LeRoy Gresham to J. G. Machen, May 2, 1923, and J. G. Machen to LeRoy Gresham, May 5, 1923.

[5] Publication date of Christianity and Liberalism, is from D. G. Hart, Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1994; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995), 62; regarding New Testament Greek for Beginners, see N. B. Stonehouse, J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Memoir (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1954; reprint, Philadelphia: Orthodox Presbyterian Church Committee for the Historian, 2004), 33, on the page is a letter of October 23, 1923, from B. L. Gildersleeve to Machen, it is said that the letter is a response to one received from Machen which had been sent to Gildersleeve just after publication of New Testament Greek for Beginners; note that the pagination of the two editions of Stonehouse’s book are different.

[6] The initials stand for Franklin Verzelius Newton.

[7] Mark F. Miller, Dear Old Roanoke: A Sesquicentennial Portrait, 1842–1992 (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1992), 106; Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, vol. 3 (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co, 1915), 343.

[8] F. V. N. Painter, “Orthodoxy and Modernism,” Roanoke World-News, Tuesday, April 24, 1923.

[9] The Union Seminary Review 34, no. 3 (April 1923): 274–76.

[10] J. M. Wells, “What is Modernism?” The Union Seminary Review 34 (January 1923): 89–98; John Miller Wells (1870–1947) was born in Mississippi, educated at South Western Presbyterian University and Union Seminary, then received the Ph. D. from Illinois Western University. He served churches in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, before his presidency of Columbia Seminary, 1921–1924. He concluded his ministry in Sumter, South Carolina, serving for nineteen years. His books include Influences that Influenced the Puritan, 1897, and the publication of his Sprunt Lectures for 1936, Southern Presbyterian Worthies. He moderated the PCUS General Assembly, 1917.

[11] J. Gresham Machen, “Liberalism or Christianity,” The Princeton Theological Review 20, no. 1 (1922): 112, the article was the publication of an address delivered in substance in the Wayne Presbyterian Church, Wayne, Pennsylvania, November 3, 1921, to the 28th Annual Convention of the Ruling Elders’ Association of Chester Presbytery.

[12] Wells, “Modernism,” 98.

[13] Unless otherwise noted information in this section is from, LeRoy Gresham to J. G. Machen, July 23, 1924.

[14] Charles P. Fagnani and J.G. Machen, “Does Fundamentalism Obstruct Social Progress?” The Survey 52 (July 1, 1924): 389–92, 425–27; the article is short, so no page numbers are cited in the footnotes; Charles Prospero Fagnani was a graduate of Union Seminary, New York. He taught in Union’s Old Testament Department, 1892–1926, see, Alumni Catalogue of the Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York, 1836–1936 (New York: Union Theological Seminary, 1937), 17.

[15] Even the best civil governments will strive to bring conformity to their citizenry because a conformed populace is a controlled populace. But the worst governments go even further by suppressing the knowledge of God through expanding their rule. The examples of government intrusion Machen used in his article were, the licensing of teachers in New York through the Lusk laws; an Oregon school law being reviewed in the United States courts; the development of a federal department of education; and forbidding languages other than English being taught in Nebraska schools.

[16] Unless otherwise noted, citations are from, LeRoy Gresham to J. G. Machen, April 9, 1925, and J. G. Machen to LeRoy Gresham, April 16, 1925.

[17] The letter is in, Stonehouse, Memoir, 2004, 307.

[18] Hart, Defending, 1994, 60fn4.

[19] For the van Dyke incident information see, Hart, Defending, 60–61, 66; Stonehouse, Memoir, 2004, 307–14.

[20] LeRoy Gresham to J.G. Machen, January 6, 1925.

[21] Dr. Young was Thomas Kay Young (1885–1954) who received the BD from Union Seminary, Virginia, and pastored in West Virginia, then in Covington and Lexington, Virginia, before serving in Roanoke, 1924–30, and then at Idlewild in Memphis beginning in 1930. He was the moderator of the PCUS General Assembly in 1945 and his D.D. was given by Hampden-Sydney College in 1920.

[22] The Bend Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, Thursday Afternoon, May 21, 1925, front page.

[23] Letters used are from, LeRoy Gresham to G. Machen, April 2, 1935 and J. G. Machen to LeRoy Gresham, June 4, 1935

[24] Arthur is Arthur Webster Machen, II.

[25] LeRoy Gresham to Arthur Machen, April 15, 1935, and an unnamed and undated newspaper clipping accompanying the letter titled, “Former Salemite Loses His Life in Drowning Accident.”

[26] It appears Machen sent Loy and Jessie a letter quickly when he heard that Francis died, and the letter of June 4 is his delayed response to the April 2 letter.

[27] James H. Blackstone and John Andrew Kauffroth were both members of Westminster Theological Seminary’s class of 1934.