The following excerpt about one minister’s persistence estblishing a seminary in eastern Tennessee is extracted from J. E. Alexander’s A Brief History of the Synod of Tennessee, From 1817 to 1887, Philadelphia: MacCalla and Company, 1890, 18-20. It is an example of how local efforts with little resources can accomplish great things under good leadership. The Synod of Tennessee was at the time of the seminary’s founding in 1819 New School. Harold M. Parker, Jr. commented in the italicized paragraph below from The United Synod of the South: The Southern New School Presbyterian Church, 1988, page 101, about the importance of The Southern and Western Theological Seminary. Parker has also published an article about Maryville and the seminary, “A School of the Prophets at Maryville,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34 (1975): 72-90; reprinted in his Studies in Southern Presbyterian History, Gunnison: B. & B. Printers, 1979, 110-128.

The seminary at Maryville, Tennessee, although largely neglected by church historians, nevertheless played a dynamic role in the southern New School in general, in East Tennessee in particular. A total of 159 ministers were trained by Isaac Anderson, who for many years was the only faculty member. Almost to a man, the students came from East Tennessee. They largely returned to the hills and vales whence they had come. They came from that hardy Scotch-Irish stock which made two valuable contributions to the spiritual life of the South: Introducing Presbyterianism to the region and providing an impulse to the education of their youth.

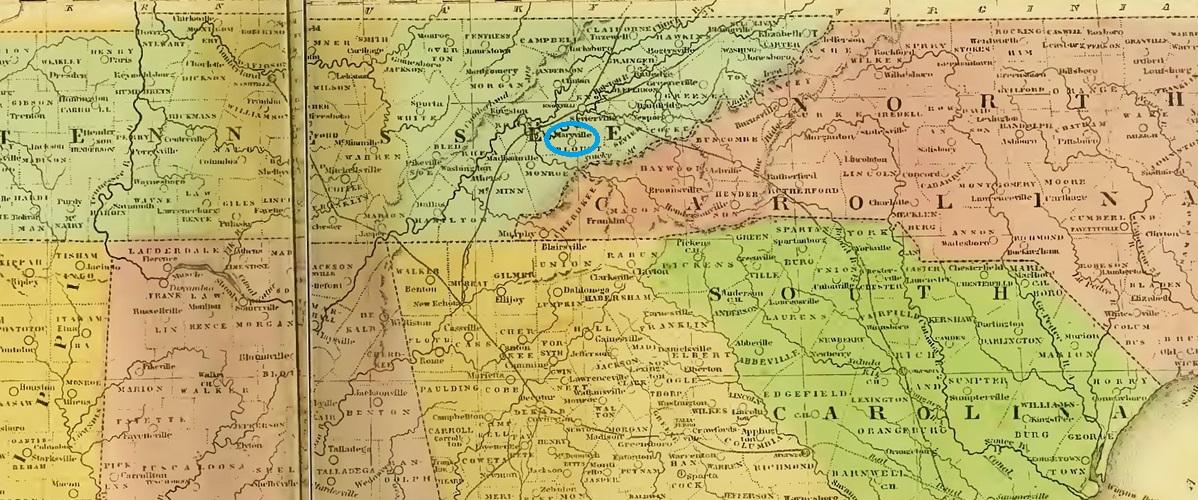

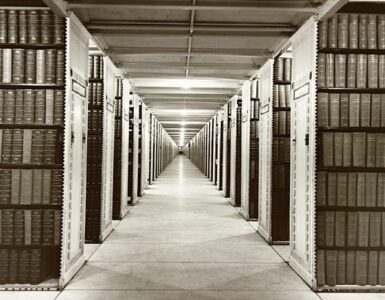

The portrait of Isaac Anderson was located through Log College Press’s listing which includes for download a biographical memoir and iisues of a serial he edited, see “Isaac Anderson (1780-1857).” The map is from Olney’s School Atlas, 1829.

Barry Waugh

The Southern and Western Theological Seminary, Maryville, Tennessee

The founder of Southern and Western Theological Seminary was the justly celebrated Dr. Isaac Anderson, born and educated, until partly through his theological studies, in Rockbridge County, Virginia. When twenty-one years of age, he came with his father to Tennessee to settle in Grassy Valley, near Knoxville. He completed his theological studies under the Rev. Samuel Carrick, and was installed pastor of Washington Church, in Knox county, in 1801. Having taught some in Virginia, and having a decided taste for that employment, he established Union Academy in the bounds of his congregation, where he educated a considerable number of young men.

The founder of Southern and Western Theological Seminary was the justly celebrated Dr. Isaac Anderson, born and educated, until partly through his theological studies, in Rockbridge County, Virginia. When twenty-one years of age, he came with his father to Tennessee to settle in Grassy Valley, near Knoxville. He completed his theological studies under the Rev. Samuel Carrick, and was installed pastor of Washington Church, in Knox county, in 1801. Having taught some in Virginia, and having a decided taste for that employment, he established Union Academy in the bounds of his congregation, where he educated a considerable number of young men.

In 1811, he accepted a call to New Providence Church, in Maryville, Tennessee, where he continued to teach in connection with pastoral duties.

Having made extensive preaching tours in the first ten years of his ministry, he became deeply affected, in view of the want of preaching and religious instruction, in the settlements which he visited, and was earnestly desirous of having them supplied with ministers of the Gospel. He wrote to the Home Missionary Societies, describing the moral and religious destitution, and entreating them to send missionaries to break to them the bread of life, but they were unable to furnish the needed help. Being a delegate to the General Assembly in 1819, he visited Princeton Theological Seminary and pleaded with its students that some of them should come and preach the Gospel to perishing multitudes in East Tennessee. But he pleaded without success. He returned with a strong and abiding conviction that ministers must be provided at home, and, feeling his personal responsibility, he gathered a class of five pious young men and commenced the great labor of his life by instructing them in theology.

At this point the Synod of Tennessee took up the work, and in the autumn of 1819 they adopted a plan of the “Southern and Western Theological Seminary,” and, hoping that it would become what was implied in its name, they published an address to the public, and sent letters to the Synods of North Carolina, Kentucky and Ohio, inviting their cooperation in this important enterprise; at the same time they chose a Board of Directors and appointed the Rev. Isaac Anderson professor of didactic and polemic theology.

Thus, did the fathers of the Synod of Tennessee boldly attempt to provide by founding a seminary of their own for training a pious and godly ministry for the great Southwest while it was yet mostly a wilderness. The seminary was started by Dr. Anderson with a class of five in a humble brown house near his own dwelling on the main street of the small village of Maryville. To this he afterwards added a lot adjoining a house in which he put a steward at one hundred dollars a year and boarding for his family as a compensation for preparing meals for the students. Without salary he taught many years, giving tuition free to most of the candidates for the ministry, and even boarding many of them at a cost to himself sometimes of from $400 to $600 a year. In 1826, a farm of 200 acres, with a boarding-house, was purchased for $2500, raised mainly by the Rev. E. N. Sawtell. The cost of boarding a student was then reduced to the minimum of $20 per year in money, aided by laboring a certain portion of each day on the farm. Contributions were made by surrounding churches and benevolent individuals in all kinds of produce and in various articles of clothing.

The hopes and expectations of the Synod that they might gain the cooperation of the adjoining Synods of North Carolina, Kentucky and Ohio were disappointed, and they were thrown upon the liberality and resources of a limited field of new settlers, mostly poor and unaccustomed to contribute to such institutions. Buildings, library, professors and endowments were wanted; the Synod itself was not a unit in its encouragement and support; some thought that it would be a seminary of Hopkinsianism [i.e. New School]; its friends differed as to the place where it should be permanently located — some would have had it removed to Murfreesboro, others to Rogersville, or wherever it could obtain the most money or other facilities — rendering all uncertain, and to its professor greatly discouraging. Finally, amid these agitated waters, the seminary was anchored at Maryville.

In view of these difficulties, it seems that the Synod could not have succeeded had not God endowed its founder and professor with a power of endurance and a spirit of devotion, self-sacrifice and consecration to his great undertaking, which special grace alone could bestow. His entire course demonstrated the sincerity of his declaration, “If any one passion has governed me more than another, it is to have qualified, devoted Presbyterian ministers greatly multiplied.”

The measure of his success in this chief end of his ambition and efforts is indicated in the following passages: Writing to a friend in 1833, he says: “Already I have borne no ordinary heat and burden for twelve or fifteen years, as you well know, and yet about sixty ministers have gone from this institution to bless as many destitute regions with evangelical labors. Revival after revival has instrumentally been produced by their labors, and many hundreds have rejoiced in the hope of the Gospel.” Again, in 1844, he says: “Amid poverty, self-denial and overwhelming exertions, the seminary has sent out nearly 100 laborers into the field, who have gathered hundreds and hundreds into the fold of the Good Shepherd.”

The charter incorporating the institution provided that the Trustees be elected by the County Court. Dr. Anderson desired to place the seminary entirely under the control of the Synod. This was effected by an amendment of the charter in 1845. These Trustees were to report annually to the Synod all matters of interest relative to the attendance, instruction and financial condition of the institution. These reports were read and discussed, and often principally occupied the time and attention of the Synod in devising ways and means for sustaining their struggling seminary. The fifth annual report of the Directors, made in 1824, is the first that has been recorded in the minutes of our Synod. They gratefully acknowledge that God had been better than their fears, for they had feared that even if the means for supporting worthy candidates could be had, the pious young men might not be found. But God had so powerfully revived the churches that a very encouraging number of pious youths had already entered upon a course of study with a view to the gospel ministry. The next year this class of students numbered twenty-five, and six of these were students of theology and nineteen of them were engaged in preparatory studies, being yet too deficient in literary attainments to commence the study of divinity.

In 1827, the Rev. William Eagleton, who, for a year or two, had been assisting Dr. Anderson in the literary department, was elected professor of sacred literature, and the Rev. Robert Hardin, D.D., professor of ecclesiastical history and church government.

In 1832, the Synod, for the first time, appointed a committee to attend at the annual examinations, and to report to them on the character of the instruction and scholarship in the institution. In 1833, the Trustees reported the finishing of a new college building, the election of the Rev. Fielding Pope as professor of mathematics and philosophy; also the presence of 69 students, 30 of whom had the ministry in view, and 14 were in the theological department. Thus, far 60 had been sent into the ministry from this infant and struggling institution.

From this time, however, the number in the study of theology began to and continued to decline. For this decline two reasons were apparent. First, other theological seminaries with better equipment were now attracting some of our theological students; and secondly, the seminary at Maryville became less able to sustain its poor and pious students, in the following way: The cheap method of boarding on the farm connected with manual labor had been broken up by the Presbyterian Education Society’s aiding this class of students for a few years from 1831, so that manual labor on their part was no longer needed. But in 1838 or 1839 that society withdrew all such aid, on the ground “that the institution was not equipped for its complex work of education.” Thus, both the labor system and the foreign aid failed, and the professors were compelled to send away candidates whom they could not assist.

The offensive reason assigned by the Education Society had, however, a good effect in that it powerfully stimulated the efforts of the Synod, Trustees, and others in prosecuting with greater zeal and efficiency measures both for an increase of the teaching force and for the endowment of the existing professorships. Still, however, the institution continued to decline as a school of theology and to assume the character of a college until in 1842, when a charter was obtained and the name of “The Southern and Western Theological Seminary ” was changed into that of ” Maryville College.” Yet the institution continued to give instruction to some students in theology until 1855.

The professors at the date of the charter were Dr. Isaac Anderson in Theology, the Rev. Fielding Pope in Mathematics, and the Rev. J. S. Craig in Languages.