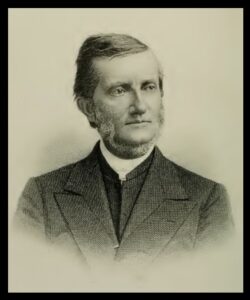

Melancthon Williams, born September 19, 1816, was the first child of Peter and Phebe (Williams) Jacobus. His father owned a saddlery and harness making factory that abutted the family property in Newark, New Jersey. Mrs. Martha Hinsdale directed his early education at the local schoolhouse where he began studying Greek and Latin at the age of eight. He advanced to continue studies at Newark Academy. By the time he was twelve, Melancthon was working in the family factory as a colleague of the apprentices and journeymen while he kept up his studies. His father had warned him about the rough ways of some of the factory workers, which Melancthon found to be true through “times of sore temptation in which the loose habits of the apprentices were hurtful to me, notwithstanding all my father’s caution” (xi). In the case of the apprentices particularly, his comradery with them was challenging because they received bed and board within his home, and it was tough sometimes to be a Joseph and flee temptation. However, along with testing times was the benefit of the same salary the other men received. His family was historically Reformed Dutch, but they attended First Presbyterian Church which was served by William T. Hamilton and Joshua T. Russell. His father was an elder and Melancthon says of his father’s instruction concerning worship,

Melancthon Williams, born September 19, 1816, was the first child of Peter and Phebe (Williams) Jacobus. His father owned a saddlery and harness making factory that abutted the family property in Newark, New Jersey. Mrs. Martha Hinsdale directed his early education at the local schoolhouse where he began studying Greek and Latin at the age of eight. He advanced to continue studies at Newark Academy. By the time he was twelve, Melancthon was working in the family factory as a colleague of the apprentices and journeymen while he kept up his studies. His father had warned him about the rough ways of some of the factory workers, which Melancthon found to be true through “times of sore temptation in which the loose habits of the apprentices were hurtful to me, notwithstanding all my father’s caution” (xi). In the case of the apprentices particularly, his comradery with them was challenging because they received bed and board within his home, and it was tough sometimes to be a Joseph and flee temptation. However, along with testing times was the benefit of the same salary the other men received. His family was historically Reformed Dutch, but they attended First Presbyterian Church which was served by William T. Hamilton and Joshua T. Russell. His father was an elder and Melancthon says of his father’s instruction concerning worship,

My father encouraged me to take down in the church the text and division of the sermon, and at noon-time and evening I was expected to transcribe these memoranda, with as full additions as I could recall from memory. This was a very useful exercise, inducing attention, and concentration, and cultivating an interest in the sermon. Two or three books of sermon outlines I have well filled as a result of such training. (xii)

This would have been an effective way to both teach the boy to listen to the sermon and when the notes were revised at noon and night, his memory would be jogged for further information. Added to his father’s program of instruction was a review of the catechism as taught at church.

At the age of fourteen his father sent him to a boarding school in nearby Bloomfield, New Jersey. The principal was Albert Pierson who also taught Latin. Among Jacobus’s classmates were several candidates for the ministry. At this point in life, he planned to become a lawyer even though his parents had devoted him from birth to the Gospel ministry. When he first appeared before the session to unite with First Church, the elders postponed admitting him to communion because one elder commented that Melancthon was “given to quickness of temper, which sometimes got the advantage” (xvi). At the time, communion was celebrated annually at First Church in a communion season, and the young man would go on to be admitted the following year.

As an alternative to practicing law, he contemplated taking a partnership in his father’s business. It was an obvious opportunity and others told him it would be the best thing for him to do. But his reoccurring sense of call to the ministry kept him from serious consideration of any other vocation.

Before a profession could be entered, some additional education was needed and the nearby village of Princeton was the obvious choice for college, so after remedial work in algebra with a tutor he matriculated with the sophomore class to the College of New Jersey, September 1831. Melancthon had surely seen the college before, but his encounter with the campus as a new student in a wagon hauling saddles and harnesses was daunting.

We rode into town on the open wagon which carried its load of goods, and as I caught the first sight of the Old North College [Nassau Hall], with its prison look, I felt a cold chill run over me, of shrinking from the ordeal I was to undergo. (xvi)

Despite his apprehension, he was a proficient student because as a junior he was chosen by the Cliosophic Society as an orator. At the end of his senior year, he was assigned first honors and was charged with the college’s oldest student honor, delivering the Latin Salutatory. After graduation, one of his professors, James W. Alexander, encountered him on campus, shook his hand vigorously while saying to him, “I shall always be glad to hear of your prosperity.” These few words of encouragement from a respected mentor remained fresh in Jacobus’s thoughts for the rest of his life, which shows how a simple but sincere comment from a mentor can yield lasting results for a student.

The question for Melancthon was, what is next? He was offered the opportunity to become a fellow and tutor, but James Richards, his home pastor, advised him not to be a pedagogue since he was planning to be a preacher. Instead, he decided to take a year off from formal schooling, return to Newark, and help his father with the harness and saddlery business. Back home, his friends and neighbors believed it providential that he was home because the harness business could one day become his own and his labor would help his father. He was no longer laying out pieces of leather, nor cutting and sewing as he did when a young man, but instead he took care of accounts receivable, sales, correspondence, and listened to complaints from customers.

With the ministry still in mind, he left Newark to begin studies at Princeton Seminary in the fall of 1836. His professors included Archibald Alexander, Samuel Miller, J. Addison Alexander, and John Breckinridge. It was a particularly interesting time to be on campus because theological discussions “were rife in the church” (xix). Debating clubs were formed among the students. Samuel W. Fisher and Thomas Wikes took the side of the New England Theology, and John McAuley dealt much with Nathaniel W. Taylor’s teaching that “all sin consists in voluntary action” (xix). He remained at the seminary as a Hebrew tutor assisting Addison Alexander. The 200.00 salary must have been appreciated after three years of paying seminary expenses. He wrote a commentary on Malachi at Addison Alexander’s request, which cultivated his own interest in exegetical work and commentaries.

While teaching Hebrew at Princeton Seminary he met Isaac Nordheimer who was a Jewish scholar educated in rabbinical schools in Europe and had received the Ph.D. from the University of Munich. He was teaching Arabic and Semitics at New York University and Union Theological Seminary when Jacobus met him during one of his library visits to Princeton to work on his Hebrew grammar. The two became friends and Nordheimer gave him an inscribed set of his grammar. Nordheimer allowed Jacobus to copy his notes on Syriac and Arabic that he had compiled hoping to publish as grammars, but he was not able to do so because of his death at only thirty-three years of age in 1842. Jacobus was much appreciative of time spent with his friend, but saddened when he died so young of the red death, tuberculosis. Edward Robinson, a colleague of Nordheimer at Union Seminary, said he should be acknowledged as “standing at the head of the scholars of the new world, in an exact and familiar acquaintance with the whole range of the Hebrew language and its philology” (see notes).

While at Princeton Jacobus was licensed by the Presbytery of New Brunswick at a meeting in First Church, Freehold, New Jersey. Though limited by his teaching work at the seminary, he was able to fill pulpits occasionally and one of the churches was the Old School First Church, Brooklyn, which had separated from the New School First Church served by Samuel H. Cox. The Old School Church was meeting in a rented facility. Cox would be a New School leader and moderator of its General Assembly in 1846. Jacobus’s autobiography describes the Old School group as the “remnant” alluding to the faithful Old Testament Jews that had not bowed the knee to false gods and turned from God’s Law. Jacobus was invited to preach to the dislocated remnant and the congregation was encouraged by his ministry. After the church obtained counsel affirming Jacobus’s gifts from Benjamin H. Rice, Archibald Alexander, Samuel Miller, and others at Princeton Seminary, he was given a call that he accepted after wrestling with his change in plans from teaching Hebrew. He was received by the Presbytery of New York from the Presbytery of New Brunswick, August 3, 1839, then ordained and installed in Brooklyn, September 15, 1839. In January 1840 he married Sarah, the eldest daughter of Samuel Hayes, M.D., of Newark.

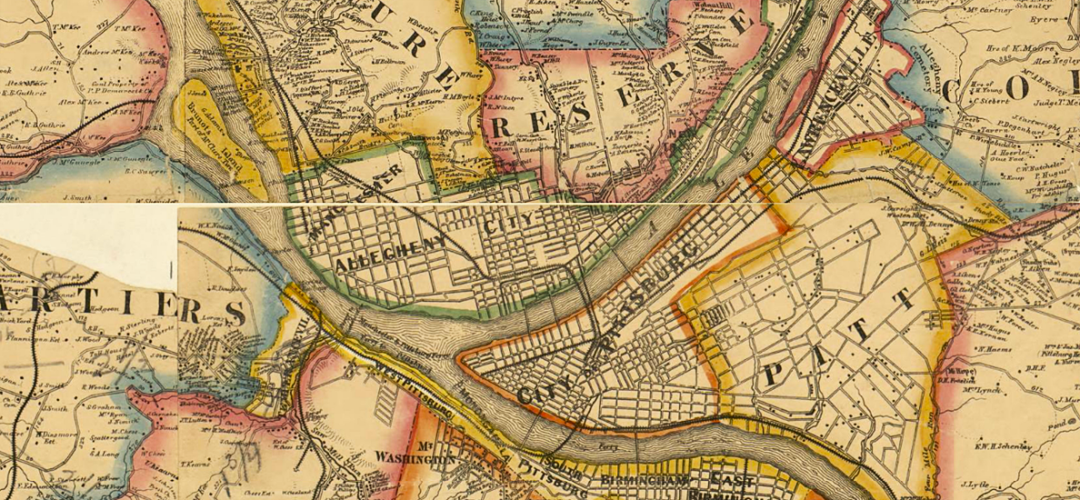

His ministry in Brooklyn was fruitful, however his pastoral work combined with completion of the first volume of what he hoped would be a commentary on the entire Bible contributed to health issues requiring a time of convalescence. As was fashionable for relief from stress and sickness in the era, he took off on a grand tour that included Europe, the Holy Land, and Egypt. While overseas he was offered and accepted the chair of Oriental and Biblical Literature at Western Seminary in Allegheny City. Upon returning home to Brooklyn he resigned from First Church, Brooklyn, after twelve years and relocated to assume teaching duties in Western Seminary in the spring of 1852.

He found teaching in the seminary pleasing and it allowed time to pursue completion of his Bible commentary. Matthew was already published; Mark and Luke made up volume two, which was issued 1853; and then in 1856, John was published. He completed Acts in 1859. The Gospels set was republished in Edinburgh in 1862 and the two volumes providing commentary on Genesis were published 1864 and 1865. After six years teaching seminary a call was offered by Central Presbyterian Church (Old Fifth) in Pittsburgh which he accepted and continued serving for fourteen years while remaining at Western. James A. Walther commented that during the dark decade before the Civil War, Western suffered a fire that destroyed an old building. The campus was on a hill making it clearly visible to the locals, one of whom commented, “the preacher factory is on fire,” possibly indicative of the rise of industry and the less than appreciative population. Walther says of Jacobus that “One bright spot in the decade was the coming of M. W. Jacobus” (p. 141). Even though the campus had enrollments as high as 150, funds were still short, and the faculty had to take additional jobs because the seminary could not pay them.

When the seminary began in the fall of 1876, Jacobus delivered the convocation address, “Bible Study, Professional and Popular.” On his last Friday he attended to his usual teaching and pastoral responsibilities, but then on Saturday, October 28, to the surprise of all he died suddenly in the morning. From the description in his autobiography by his son-in-law it must have been a massive heart attack. He was survived by Sarah, their three daughters and two sons. One daughter was named Kate, and the two sons were Samuel H. Jacobus, who was the financial manager of the Jacobus and Nimick Manufacturing Company, and the younger son, M. W. Jacobus, Jr., was dean of Hartford Theological Seminary and Hosmer Professor of New Testament Exegesis.

Jacobus was honored with the Doctor of Divinity by Jefferson College, 1852, and the Doctor of Laws, by the College of New Jersey, 1867. But he appreciated most of all the honor of representing the Old School as its last moderator in 1869 and as joint moderator with the New School’s Rev. Philemon H. Fowler, D.D., for the reunited General Assembly 1870. However, like Matthew Henry, he was not able to complete his entire Bible commentary.

Jacobus issued several publications that are available for download on the Log College Press website, “Melancthon Williams Jacobus, Sr. (1816-1876).” He wrote some interesting titles concerning children and their education, such as, The Catechetical Question Book: Matthew-Applying Throughout the Questions of the Westminster Catechism, 1840, 1849; Child’s Hymns on the Lord’s Prayer, 1849; The Catechetical Question Book: Mark, 1854; and the last title likely with his own life in mind, The Duty of Dedicating Our Sons to God, For the Gospel Ministry, no date.

Barry Waugh

Notes—Header is cropped from “Map of Allegheny Co., Pennsylvania: From Actual Surveys,” Philadelphia: Smith, Gallupp & Hewitt, 1862, as found in the digital collection of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. The primary source is, Matthew Newkirk, ed., The Christian’s Heritage, and Other Sermons, By the Late Melancthon W. Jacobus, D.D., LL.D., Together With An Unfinished Autobiography, New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1878; the autobiography is on pages ix-xxvii. The quote about Nordheimer is from Shalom Goldman, “Isaac Nordheimer (1809-1842): ‘An Israelite Truly in Whom There Was No Guile’,” American Jewish History 80 (Winter 1990-1991), quote 213, article 213-229. Family and funeral information is from The Pittsburgh Commercial, Saturday, November 4, 1876, page 1, and Pittsburgh Daily Gazette, Tuesday, October 31, 1876, page 4. On Western Seminary see, James A. Walther, ed., Ever a Frontier: The Bicentennial History of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1994. Helpful titles for New York Presbyterianism are, Robert H. Nichols, Presbyterianism in New York State, Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1963; Theodore F. Savage, The Presbyterian Church in New York City, New York: The Presbytery of New York, 1949; and Dorothy G. Fowler, A City Church: The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York 1716-1976, New York: The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, 1981.