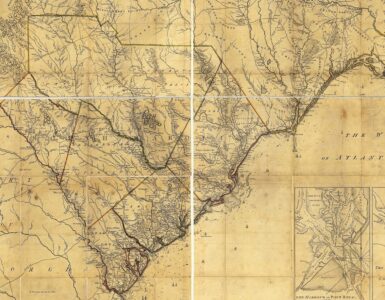

Introduction. The church at Leyden was the mother church for the Pilgrim congregation in Plymouth Plantation in New England. John Robinson was pastor of the Leyden congregation and continued ministy there until his death in 1625. During his era the Plymouth Pilgrims and the Leyden Church were tied together in mutual ministry despite their separation by many miles. As the editor of Robinson’s works Robert Ashton expressed it, the churches were identical and it was agreed that members returning to Leyden should be “reputed as members, without further dismissal or testimonial, and therefore entitled at once to take their places at the sacramental board, and to exercise their rights in the meetings of the church.” These dissenting Christians had separated from the Church of England and were living in exile in Leyden, Amsterdam, and Plymouth Plantation so they could practice their doctrine as congregational churches with each church bound by its covenant.

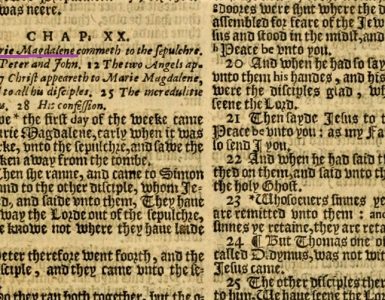

The text following this introduction is transcribed from volume 3 of The Works of John Robinson, London, 1851, pages 490-91. Ashton says he transcribed the list of ten principles of the congregational churches from George B. Cheever, The Pilgrim Fathers: or, The Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, New England, in 1620, published 1862. Ashton determined that Cheever agreed with earlier works by Thomas Prince, A Chronological History of New-England: in the Form of Annals…to the Arrival of Gov. Belcher, 1730, 1736, and George Punchard’s History of Congregationalism From About A.D. 250 to 1616, 1841.

The Pilgrims developed their congregationalism in opposition to the episcopal polity of the Church of England by giving primary governance to each congregation rather than to a higher entity. Each church was united by a covenant among its members. The local church shepherds in the Netherlands and Plymouth were called elders and they constituted a presbytery (session for Presbyterians). According to the 10 points that follow, the Pilgrims’ elders exercised ruling and teaching functions; the office of deacon is clearly defined and emphasized; and point 6 describes this as “in some respects, of three sorts, but in others, two.” Also notice in 6.B. that the deacons were in some manner “to minister at the Lord’s table.” However, they did not subscribe to the Westminster Standards because they could not since they would not exist until the 1640s.

If interested in further reading the following articles are available on this site: “Thanksgiving, Presbyterians, George Washington, & Constitutions,” posted November 18, 2021; “Pilgrims & Plymouth: 400 Years Later,” November 21, 2020; “Thanksgiving, William Bradford, 1590-1657,” posted November 28, 2019; “Thanksgiving 2018,” posted November 21; and “The First Thanksgiving, Edward Winslow, 1621,” November 21, 2017. Also on this site is the article “Aaron W. Leland, Congregationalism and Grassroots Presbyterianism,” which includes information about the influence of congregational polity on presbyterian polity, particularly in the South. You will find in the articles that published sources are given for the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving, such as William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation. The header shows “Pilgrim Exiles, by George H. Boughton” from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection in the New York Public Library digital collection. A memorial for John Robinson was erected in Leyden by The National Council of Congregational Churches of the United States according to the book, The John Robinson Memorial Tablet, Leyden, Holland, July 24, 1891, Boston.

Barry Waugh

Principles of the Plymouth Church

1. That no particular church ought to consist of more members than can conveniently watch over one another, and usually meet and worship in one congregation.

2. That every particular church of Christ is only to consist of such as appear to believe in and obey him.

3. That any competent number of such, when their consciences oblige them, have a right to embody into a church for their mutual edification.

4. That this embodying is by some certain contract or covenant, either expressed or implied, though it ought to be by the former.

5. That being embodied, they have a right of choosing all their officers.

6. That the officers appointed by Christ for this embodied church, are, in some respects, of three sorts, but in others, two:

A. Pastors, or teaching elders, who have the power both of overseeing, teaching, administering the sacraments, and ruling too, and being chiefly to give themselves to studying, teaching, and the spiritual care of the flock, are therefore to be maintained.

Mere ruling elders, who are to help the pastors in overseeing and ruling, that their offices be not temporary, as among the Dutch and French Churches, but continual; and being also qualified in some degree to teach, they are to teach only occasionally, through necessity, or in their pastor’s absence, or illness; but being not to give themselves to study or teaching, they have no need of maintenance [salary].

That the elders of both sorts form the presbytery [i.e. session] of overseers and rulers, which should be in every particular church; and are in Scripture called, sometimes presbyters, or elders; sometimes bishops, or overseers; and sometimes rulers.

B. Deacons are to take care of the poor, and of the church’s treasure; to distribute for the support of the pastor, the supply of the needy, the propagation of religion, and to minister at the Lord’s table, &c.

7. That these officers, being chosen and ordained, have no lordly, arbitrary, or imposing power, but can only rule and minister with the consent of the brethren.

8. That no churches, or church officers whatever, have any power over any church or officers, to control or impose upon them; but are equal in their rights and privileges, and ought to be independent in the exercise and enjoyment of them.

9. As to church administrations, they held that baptism is a seal of the covenant of grace, and should be dispensed only to visible believers, with their non-adult children; and this in primitive purity, as in the times of Christ and his apostles, without the sign of the cross, or any other invented ceremony. And that the church or its officers have no authority to inflict any penalties of a temporal nature; excommunication being wholly spiritual, in a rejection of the scandalous from the communion of the church.

10. And lastly, as for holy days. They were very strict for the observation of the Lord’s Day; in a pious memory of the incarnation, birth, death, resurrection, ascension, and benefits of Christ; as also solemn fastings and thanksgiving, as the state of providence requires. But all other times not prescribed in Scripture, they utterly relinquished. And, as in general, they could not conceive anything a part of Christ’s religion, which he has not required, they therefore renounced all human right of inventing, and much less of imposing it on others.

“These,” says Thomas Prince, “were the main principles of that scriptural and religious liberty, for which this people suffered in England, fled to Holland, traversed the ocean, and sought a dangerous retreat in these remote and savage deserts of North America; that here they might fully enjoy them, and leave them to their last posterity.”