On the night of September 13, 1814, the British commenced bombarding Fort McHenry in Baltimore’s harbor. Francis Scott Key was viewing the cannon and rocket fire from the deck of a ship. The grand display of explosions as the fortress stood with its massive American flag waving inspired Key to compose The Star-Spangled Banner. It was truly a grand moment in the history of the United States as the mighty navy of the British empire was repulsed and the city was saved from invasion, pillaging, and servitude. Less than a month earlier the British had marched into Washington and burned the nation’s capitol. In remembrance of the soldiers that defended Baltimore, Lieutenant Colonel David Harris ordered the officers and soldiers of the First Regiment of Artillery, Maryland Militia, to gather in Washington Square “in full uniform” with the left arms of the commissioned officers wrapped with crepe (a symbol of mourning and honor) to march to First Presbyterian Church where Pastor James Inglis delivered a sermon on “the Lord’s Day morning” of October 2. The sermon was designed for the unique gathering of soldiers whose relationships to God were unknown. The Bible text was Daniel 5:23, “The God in whose hand thy breath is, and whose are all thy ways, hast thou not glorified.” Two simple points were made—first, “it is our duty to glorify God”; second, may “the spirit of God enlighten our minds to know the truth, and incline our hearts and will to do that which is right in all things, to the honor of his holy name.” It is a simple, straightforward sermon full of quotations from the Bible and is the type of exposition a minister might deliver to a group with many non-Christians. He encouraged the listeners to “prepare to meet your God and live every day as your last.” After mentioning the awful fires and destruction caused by the bombardment, Inglis defined true patriotism.

On the night of September 13, 1814, the British commenced bombarding Fort McHenry in Baltimore’s harbor. Francis Scott Key was viewing the cannon and rocket fire from the deck of a ship. The grand display of explosions as the fortress stood with its massive American flag waving inspired Key to compose The Star-Spangled Banner. It was truly a grand moment in the history of the United States as the mighty navy of the British empire was repulsed and the city was saved from invasion, pillaging, and servitude. Less than a month earlier the British had marched into Washington and burned the nation’s capitol. In remembrance of the soldiers that defended Baltimore, Lieutenant Colonel David Harris ordered the officers and soldiers of the First Regiment of Artillery, Maryland Militia, to gather in Washington Square “in full uniform” with the left arms of the commissioned officers wrapped with crepe (a symbol of mourning and honor) to march to First Presbyterian Church where Pastor James Inglis delivered a sermon on “the Lord’s Day morning” of October 2. The sermon was designed for the unique gathering of soldiers whose relationships to God were unknown. The Bible text was Daniel 5:23, “The God in whose hand thy breath is, and whose are all thy ways, hast thou not glorified.” Two simple points were made—first, “it is our duty to glorify God”; second, may “the spirit of God enlighten our minds to know the truth, and incline our hearts and will to do that which is right in all things, to the honor of his holy name.” It is a simple, straightforward sermon full of quotations from the Bible and is the type of exposition a minister might deliver to a group with many non-Christians. He encouraged the listeners to “prepare to meet your God and live every day as your last.” After mentioning the awful fires and destruction caused by the bombardment, Inglis defined true patriotism.

True patriotism is a Christian virtue. Our religion is the nurse of loyalty and public spirit. It authorizes us to contend—it teaches us to die—for the sanctity of our altars, and the security of our dwellings—for the legitimate rights of our compatriots, and the tranquility of those who shall come after us.

Inglis echoes the Bible’s teaching concerning the Christian’s relationship to the government as given in 1 Timothy 2:1-2 and Romans 13:1-7, and he reflected the political atmosphere of the era which esteemed the common good. A good Christian not only worships God but is also to be a good citizen.

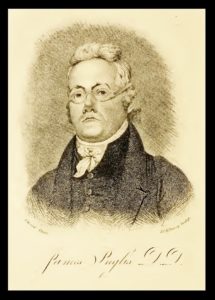

According to the limited information available about James Inglis, he was born in Philadelphia in 1777 to James and his unnamed mother. His father had emigrated from Scotland about twenty years earlier. His mother was born in Ireland of French Huguenot parents. When French-Irish-Scotch American James was about three years old his family moved to New York where he received preparatory instruction from local teachers. Following graduation from Columbia College with the class of 1795, he studied law with Alexander Hamilton and was admitted to the bar in New York. At some point he left the practice of law to prepare for the ministry. As did many, he turned to John Rodgers of the Collegiate Presbyterian Church in New York for his theological preparation and was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of New York in the fall of 1801. The following February he completed testing his gifts for ministry and accepted a call to First Church in Baltimore succeeding Dr. Patrick Allison who had ministered for thirty-seven years. Inglis was installed in April and the president of the College of New Jersey, Samuel Stanhope Smith, delivered the sermon for the occasion. In the fall of 1802 he married Jane the daughter of Christopher Johnson of Baltimore. Inglis was honored with the Doctor of Divinity by the College of New Jersey in 1811. This scanty information provides but a snapshot of his years thus far.

In his day Inglis was known well enough within the Presbyterian Church to be elected moderator of the General Assembly in 1814. The meeting convened May 19 and ended fifteen days later on June 2. The place of meeting was Second Church, Philadelphia, but it was hoped the presbyters would be moving to the originally scheduled location at First Church which was undergoing repairs necessitated by a fire. Added to the usual items on the docket such as enrolling commissioners, appointing committees, and reviewing synod records were several overtures and other needs requiring deliberation.

There was a report on church discipline of baptized children that was assigned to a committee which reported its recommendations, but they were tabled, then taken up later, and finally postponed indefinitely.

A reoccurring concern among Presbyterians was financing education for “poor and pious youth” so they could study divinity and enter the ministry. With Princeton Seminary about to begin its third year, the funding of scholarships for those in need was an important issue. Another decision regarding Princeton was approval of the purchase of six acres of land for the campus at the price of 200.00 per acre. The General Assembly encouraged presbyteries to raise funds for the seminary and Moderator Inglis appointed a committee to design a donation form.

During the 1813 Assembly a controversial issue had been ordination sine titulo, which means ordination of a candidate who does not have a pastoral call to a particular church or churches. The report of the committee charged with the issue was adopted by the Assembly and sent down to the presbyteries. The responses were reported to the 1814 Assembly. The presbyteries found the recommendations unsatisfactory and “negatived” them.

A publisher in Philadelphia, Thomas Dobson, presented a two volume set of the first American edition of the Hebrew Bible which was placed on the clerk’s table for examination; ministers are often afflicted with bibliomania, so the books on the table were likely perused during breaks in the proceedings.

A committee was appointed to compose a petition to the U.S. Congress about the government profaning the Sabbath with its mail delivery policy. During the nineteenth century, the Presbyterians and other denominations were concerned about the increasing lack of concern for worship and rest on the Lord’s Day and they promoted Sabbath societies within their congregations while reminding the government of the Sabbath’s universal obligations.

There was extensive debate about an appeal from the session of Third Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, concerning the decision of the Synod of Philadelphia instructing the Presbytery of Philadelphia to require the session to call a full-time minister for the church. The church had been served by pulpit supplies for an extended time and was fiscally able to call a minister. A committee appointed for the matter provided a five-point report that was received but not deliberated because of insufficient documentation, but by the end of the Assembly the case was “after a short discussion it was agreed by all the parties concerned, and concurred in by the Assembly, that all proceedings in this case shall cease for ever.” Whether or not the use of “for ever” was an expression of exasperation or an eschatological hope is not clear.

One question which has reoccurred in varying forms in church history is the validity of baptisms performed by other denominations. This overture concerning the issue came from the Presbytery of Harmony in South Carolina.

A person who had been baptized in infancy by Joseph Priestley, LL.D., having applied for admission to the table of the Lord; should the baptism administered by Dr. Priestley, then a Unitarian, be considered valid?

Priestly was an Englishman from a Non-Conformist Calvinist background, but as a young man he renounced his theological roots for Unitarianism. The overture was “after considerable discussion” committed by the Assembly to a committee of three, and their single-paragraph report determined the baptism invalid simply because the sacrament must be administered in the “name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” which is something a Unitarian could not do.

The Synod of Geneva (New York) presented an overture to the Assembly inquiring whether a deposed minister should be viewed as excommunicated. The Assembly adopted the committee’s report which included the following statement.

In the judgment of this Assembly the deposition and excommunication of a minister are distinct things, not necessarily connected with each other, but when connected ought to be inflicted by the Presbytery to whom the power of judging and censuring ministers properly belongs.

The court of original jurisdiction has the authority and knowledge to make its own decisions. A minister can be deposed from the ministry for reasons other than those that could lead to excommunication. Even if a minister was deposed for a grave sin, excommunication is the final step in the process of church discipline–if there is repentance, excommunication is not necessary.

A General Assembly not only supplies routes to peace and instruction but also reviews the work of ministry of its churches. As the nation expanded west the Assembly often redefined existing judicatory boundaries and added new synods and presbyteries. As Inglis led the Assembly, the Presbytery of Lancaster was separated from the Synod of Pittsburgh, and the Presbyteries of Washington (Pennsylvania) and Miami (Ohio) were separated from the Synod of Kentucky to become the Synod of Ohio. The Assembly also sent out 51 missionaries, presented a report of the ministry of the denomination with its annual Narrative of Religion, and supplied information and direction in ministry to assist the churches. Assistance is sometimes disciplinary, other times it is instructive, then there are constitutional issues, concerns about growth in sanctification, educational needs, and distribution of publications, but the key word is assist. When the final blow of the gavel was made on June 2, James Inglis was surely a tired moderator, but he had assisted the commissioners to assist the congregations.

Dr. Inglis was respected by his congregation and he had a fruitful ministry, but during his last few years conflict arose in the church and trouble began in December 1817 when it became clear during a Wednesday evening prayer meeting that he was under the influence of alcohol. The temperance movement did not arise out of nowhere; the abuse of alcoholic beverages was a problem. Eventually the drinking and other issues led to schism in the congregation between those supporting Inglis and those who did not. Added to the temperance issue were charges he violated the Sabbath, disregarded the session’s instruction to promote prayer meetings, and neglected family worship; the last two were eventually dropped. But then Inglis faced division in the session and was challenged about the way he handled elder ordination. Matters led to Inglis being charged before the Presbytery of Baltimore and he was tried in June 1818. By this point in time, he said drinking was no longer a problem. Presbytery’s discipline was calling him to stand before the Moderator and be admonished to pursue his ministry with new zeal recognizing his dependence on God. In May of the next year he was chosen moderator of the presbytery meeting.

James Inglis died in his bed of apoplexy (cerebral hemorrhage or stroke), on Sunday August 15, 1819 while his congregation waited for him to begin the morning worship service. Some sources say he died when coming from a bath, so he could have fallen and hit his head causing a hemorrhage. He was only 41. Jane predeceased him in 1812 and the seven children less than ten years of age were left without a mother. It is clear that James Inglis was well liked and respected by his fellow presbyters and much of his congregation, but it is sad that his last few years were lived with remembrance of conflict and disharmony.

James Inglis’s works include: A Sermon Delivered in the First Presbyterian Church in the City of Baltimore on Thursday, September 8, 1808: Being a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, Appointed by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Baltimore, 1808.

A Missionary Sermon, Delivered in the City of Philadelphia, May 25, 1812, before the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, by James Inglis, Baltimore, 1812.

A Discourse Delivered in the First Presbyterian Church, in the City of Baltimore, Lord’s Day Morning, October 2, 1814: Before the Lieutenant-Colonel, the Officers and Soldiers of the First Regiment of Artillery, 3rd B.M.M., and published at their request, Baltimore, 1814.

Proceedings Relative to the Erection of a Monument to the Memory of those who Fell at the battle at North Point: Including the Prayer of Bishop Kemp and the Address of the Rev. Doctor Inglis, Baltimore, 1815.

Sermons of the Late Dr. James Inglis, Pastor of the First Presbyterian church in Baltimore, Baltimore, 1820; the book includes 34 sermons and some “forms of prayer” at the end.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header is a view of Baltimore circa 1848. The portrait of Inglis is the frontispiece of his book of sermons. The number of troops in a regiment was in the hundreds; one source set the number in the 1st Regiment at 700; the church building was 4800 square feet with a balcony. The elision in “the pleasure he derived from his appropriate…and eloquent,” in the first paragraph of this article is due to damage to the original copy from which the digital version was scanned. Sites providing information about the bombardment of Baltimore include—“Maryland in the War of 1812 Celebrating the 200th Anniversary of the War of 1812” on msa.maryland.gov; the National Parks Service site page for Fort McHenry, particularly “Fort McHenry and the Star Spangled Banner”; and The National Archives page, “War of 1812 Military Records,” has considerabble online information. I have found the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy online very helpful and a scholarly flower among the weeds of many Internet sites but the entries should be read with a critical eye; the articles “Locke’s Political Philosophy” and “The Common Good” were particularly beneficial. Regarding ordination sine titulo see R. J. Breckinridge, “Presbyterian Ordination not a Charm but an Act of Government,” on the site of the Presbyterian Church in America Historical Center. The limited biographical information on Inglis was gleaned from William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 4. Also used was, A Brief History of the First Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, by William Reynolds, Baltimore, 1913. Sprague has Inglis’s year of death as 1820 but Reynolds has 1819, I have chosen 1819 because it is clear that Reynolds was using First Church records for his book and the session minutes would have likely been accurate about the pastor’s death. Also, Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia notes Inglis died on Sunday, and August 15 was on a Sunday in 1819, not 1820. Dobson’s Hebrew Bible is currently very pricey if one can be found.