As was noted in the post, “Contemporary Christian Church Music,” which provided a transcription of an article by T. E. Peck and Stuart Robinson—worship of the Lord in song has been a controversial subject particularly since the gradual transition from exclusive psalmody in the eighteenth century to inclusion of hymns by composers such as Isaac Watts. The words of Ephesians 5:19, “psalms and hymns and spiritual songs,” have been interpreted differently by those using Psalms alone and those who include hymns with Psalms.

The transcription that follows is from the minutes of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Old School, General Assembly of 1849, and it addresses this controversy. A committee had been appointed to make recommendations regarding church music, and it appears, though I am not certain, there were no ruling elders seated. The Committee on Church Music had been appointed the previous year by Moderator Alexander T. McGill but its membership changed as some appointees were excused and others were given their seats. When the report was submitted, it was signed by the following members:: John M. Krebs, (Rutgers Street Church, New York) James W. Alexander (Duane Street Church, New York), Daniel V. McLean (Freehold, New Jersey), William S. Plumer (Franklin Street Church, Baltimore), Gardiner Spring (Brick Church, New York), George Potts (University Place Church, New York), Willis Lord (Penn Square Church, Philadelphia), Charles C. Beatty (Second Church, Steubenville, Ohio), and William Jeffery (Bethany Church, Herriottsville, Pennsylvania).

What specifically was the committee to address regarding church music?

In 1843 the Old School Presbyterian Board of Publication issued Psalms and Hymns Adapted to Social, Private and Public Worship in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, which was printed in Philadelphia. It included the complete Psalter of Isaac Watts followed by 680 hymns. In a modern hymnal the music is provided with the words but in earlier hymnals, as with this one, only the words are given. Each hymn is headed with a few words describing its topic and a notation regarding the meter to which it is sung. The hymns are not titled. This seems unusual today given hymnals have the words and music for each one and a title, but the 1843 hymnal shows the transition from Psalm singing alone to Psalms and hymns. Psalms for singing simply had the number of the Psalm, the meter, and then the words. The brief preface to the 798-page collection expressed the hope that—

The collection itself comprehends what were supposed [assumed] to be the best hymns in the one now in use, with a large addition from other sources, and in sufficient variety, it is presumed, to meet all the wants of worshippers.

Unfortunately, the hymnal did not “meet all the wants of worshippers,” which resulted in the appointment of the Committee on Church Music. The instrument by which the church music issue came to the floor of the Assembly was an overture from the Synod of Philadelphia which the Committee on Bills and Overtures reviewed and then made its recommendation.

[To] report to the next General Assembly upon the general subject of congregational singing, suggesting such scriptural measures as may seem calculated to improve it, and such remedies of existing evils as the case may seem to require. The recommendation was adopted.

The primary concern for the Committee on Church Music was improving congregational singing during worship on the Lord’s Day. As an aside, it is interesting that the 1843 hymnal designates one section “For the Lord’s Day” and not “For the Sabbath,” as might be expected. The secondary concern for the Committee was “preparation of a book of tunes adapted to our present psalmody.” Presumably, the thinking was, if tunes were more singable for the average non-musically trained congregant to sing, then more people would sing.

Congregational participation in singing is clearly not a new problem. Robinson-Peck and the report of the Committee on Church Music that follows this introduction mention factors contributing to lack of participation such as overemphasizing the choir, viewing worship music as entertainment, and the use of hired professional non-congregation members to bolster (supplant?) the congregation. On several occasions, while traveling I have worshipped in other Presbyterian churches and noticed that people simply do not sing. It is not a matter of a few here and there not singing, but instead a few here and there are singing. This is true of churches whether they are considered traditional or contemporary (these terms are used reluctantly for convenience), but it seems the more music is emphasized in a service, ironically, the less the participation of the congregation. Though the number appears to be waning, there are churches that have singing congregants. I have the privilege of membership with a congregation that sings well with a skilled director and talented accompanists under the oversight of elders who are concerned for regulated worship. Worship is not a traditional vs. contemporary issue; worship is a theological issue in that its purpose is glorifying God as we enjoy Him within the limits of liturgy given in Scripture.

I said in my introduction to the Robinson-Peck post that the Old School took a moderate position regarding the issue of church music. What I mean by moderate is the Old School did not limit its worship music to Psalms, but instead combined hymns of contemporary composition with those of the past. The addition of hymns is not only appropriate but necessary. But this raises some questions. Which hymns are to be added? What is the standard to be used (of course, Scripture, but how)? Is there an essential core of hymns that must never be removed? Are there tunes that are unacceptable, and if so, what makes them unacceptable for worship (sexual beat, originally used with worldly or atheistic lyrics)? Can adding new hymns work against the goal of united congregational singing; can removing old hymns likewise reduce congregational singing? Are the older members of congregations to be left out as too much emphasis is placed on new words and tunes (the age demographic of the United States is increasing )? Those who sing the Psalms exclusively have an advantage because the words of their worship in music are fixed, but they too may face the challenge of congregants wanting the words of Psalms updated with more up-to-date tunes. Church history, unfortunately, is often the study of division whether it was the Christological issues of the ancient church, division with the Reformation, the Old and New Schools, and many others. The issue of church music divides us as well. However, one thing both traditional and contemporary churches could agree on is the participation of church members in congregational singing. If unity cannot be found here, then the issues that divide are presuppositional and theological. The Church, whether Presbyterian or not, is divided about music, but it is certain that all of us will be singing the same words and tunes before the Throne, but could we not make an effort to unify on congregants singing in worship.

With regard to the report that follows, I found some of the comments objectionable not necessarily because of what was said but because of the way it was said. The General Assembly is the highest earthly court of the Presbyterian Church and its decency and honor should be beyond the expected in all matters. Intemperance, personal attacks, sarcasm, smart-aleck jabs, and patronizing comments have no place in the Church in general but especially in gatherings of presbyters.

Barry Waugh

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON CHURCH MUSIC

The Committee on the subject of Sacred Music, appointed by the General Assembly last year (see Minutes, A. D. 1848, pp. 18 and 55) respectfully report, that six members of the Committee, viz. the Chairman, and Messrs. Plumer, Potts, Lord, McKinley, and McNair, met, agreeably to appointment at Philadelphia on the 20th day of February last, and proceeded to the consideration of the duty which had been confided to them. After making some progress therein, the Committee, having sat through three days, adjourned, referring the further prosecution and completion of the work to the members residing in the city of New York, and authorizing them to present the result of their labors to the next Assembly.

At the commencement of their sessions, the Committee were occupied with a question concerning the extent of their powers. The overture from the Synod of Philadelphia, (see overture, number 3, Minutes, 1848, p. 18,) contemplated the appointment of “a committee to take into consideration the subject of Church Music, with special reference to the preparation of a book of tunes adapted to our present psalmody.” The Assembly’s resolution, appointing the Committee, conferred upon it no other power, expressly, than “to report to the next General Assembly, upon the general subject of congregational singing, suggesting such scriptural measures as may seem calculated to improve it, and such remedies of existing evils as the case may seem to require.” While the overture appears to embrace two points, viz. a report upon the subject, and some provision for a book of tunes, the act of the Assembly authorizes a mere report, with suggestions on certain specified points, and makes no express reference to the preparation of a book of tunes.

On the first point submitted to their consideration, the Committee offer the following remarks:

There are different opinions, in various parts of the Church, in regard to the present state of congregational singing. What the taste and usages of the churches, in one section, may highly approve, other churches, possibly, would disapprove. Conformity, in all points of opinion and practice, is, perhaps—nay, most probably—unattainable. And, in cases wherein the differences arise, not in view of unmistakable decisions of the Bible, or of our Standards, but simply from considerations of taste, convenience, longer or shorter usage, and varying application, and, indeed, varying interpretation, of the notices of this subject which are contained in the sacred oracles, much must necessarily be left to the mutual forbearance and conceded Christian liberty of God’s people. These diversities may be either rendered more tolerable, or altogether removed, by increasing intercourse and communion, by frank and friendly comparison of views, and by the influence of that more extended public discussion, which the subject is evidently destined to receive. Without entering that discussion here, or indicating any opinion, beyond that which we have just expressed; the Committee deem it to be incumbent on them to notice some other points, on which, as it seems to them, there is occasion for present animadversion.

They would specify, in the first place, the great neglect, which, in some places, appears to characterize the singing in public worship—whereby that solemn and important exercise degenerates into a careless, slovenly, unsuitable style—equally unfitted to honor God and to edify man. And this is the more inexcusable because facilities abound for making such genuine improvements in this department of worship, as would make it at once more worthy as an offering to God, more expressive of the emotions of sincere piety, and more delightful, not only to the tuneful ears, but to the tuneful hearts, of the worshippers themselves, when they would make inward melody unto God, and refresh the spirit with psalms and hymns, and spiritual songs.

But, on the other hand, while the Committee rejoice to believe—in view of the numerous communications addressed to them from various sections of the Church—that very great improvements have been successfully attempted, and a purer taste has been created, and is increasingly cultivated and cherished, the very effort for improvement is not free from some defects that need attention.

First: The great multiplication of tune books has tended to displace the old familiar melodies, which have been handed down through past generations—the offspring of the pure and pious taste of earlier times—venerable, alike, on account of their intrinsic and unsurpassed excellence, and on account of that familiar, household, and edifying use and association, which have consecrated them in the affections of the saints. While later times have furnished many valuable additions to our stock of sacred melodies, many of which have already become familiar, and are deservedly cherished, there has also been introduced into the churches, a class of frivolous, theatrical, and secular tunes, which, on account of their intrinsic character, or of their degrading associations, are entirely unfit to be used in God’s sanctuary. These should be excluded promptly, no matter what pretense of putting them to a sanctified use may be urged for their protection. The melodies of the Church should be her own in every sense—made for, and adapted to, her sacred songs. There is no deficiency of such. She has no need to rake the kennel, nor to sweep the purlieus of the theatre and the opera, nor even to ask contributions from the concert room. There is no want of skill and taste among her Asaphs, Hemans, and Jeduthans, her Gregories and her Luthers, to supply her with sacred melodies, at once worthy of their spiritual themes, and vying with the boastful productions of profaner schools.

Second: The employment of irreligious, and even immoral persons, to teach congregational singing-schools, and to officiate as precentors and choristers in public worship, is an evil, that has been confined neither to former nor to later days; but it is an evil, which should not be countenanced for a moment, and it can never be justified by the mere desire of a people to avail themselves of the professional skill of such persons, any more than the settlement of a minister of doubtful reputation solely on account of his popular talents.

Third: Singing-schools, also—although they are susceptible of being properly conducted, in such a manner as to make them cheerful assemblies, while they should be so conducted as to make them the occasions of salutary impression and devout emotion—may be, and often have been, the scenes and occasions of such rude hilarity and irreligious levity, as involve them in the same objections which are justly urged against those assemblages, whose professed design is mere worldly amusement and dissipation. This evil may be easily corrected by pastors and sessions exercising a prudent discrimination in the selection of instructors of suitable character, by being present and giving their countenance to discreet measures for securing a good government of the schools, and by employing the hallowing influence of prayer, both at the opening and at the closing of the exercises.

Fourth: There is, further, a certain tendency to forget the great design of singing in public worship, when, under cover of the zealous efforts for improvement, the music is cultivated with too great reference to its merely aesthetic and commercial uses. It degenerates into an office of simply pleasing the ear, and of attracting worldly persons to the sanctuary with too exclusive regard to the pecuniary advantage to be derived from their attendance in the support of public worship. We could name some churches where this object has been carried so far, and the means employed are so scandalous—as, for example, the hiring of operatic and other histrionic singers—that the places of worship in question, have come to be stigmatized, even by the worldly and irreligious, as the “Sunday Opera!” There is, in the degenerative motive at the foundation of such an abuse of congregational music, something so merely sensual, so disparaging to the ministration of the gospel, and so degrading to the Church and to public worship, that its character soon becomes apparent, and the Divine rebuke may be discerned in the lowered tone of piety, in irreverence, in parochial dissensions, and, not seldom, in the utter failure of the unhallowed enterprise.

Fifth: While, in some places, as yet, singing in public worship is conducted by a precentor, or a choir, and the congregation generally join their voices—in other places, a select choir performs the singing with little or no assistance from the great body of the congregation. We are free to say that we consider the latter practice as very undesirable, at the least. It results, in some cases, from the too frequent introduction of new tunes, which are repeated so seldom, and at such long intervals, that the congregation has no sufficient opportunity to become familiar with them—and this is one important reason of the dislike which is occasionally felt toward new tunes, otherwise unexceptionable. But the disuse of congregational singing arises, also, from the fact that as the more cultivated and skillful singers are apt to be collected in the choir, there is not only a corresponding diminution of the number of singers in the body of the congregations, by the transfer of voices which formerly rose from various points in the assembly, but an increased diminution is effected, because other persons, who now miss the leading voices, by whose vicinity they were encouraged to sing, have now ceased to sing at all;—and at length, if the singing of the choir happens to be very excellent, the pleasure of listening to it supersedes what ought to be the pleasure, and is the duty, of following it and uniting with it; and in the end, the mass of the worshippers sit completely silent.

We do not object to choirs. They are eminently useful as leaders. The evil alluded to is not necessarily to be remedied by disbanding them. There is a more excellent way of supplying the defect. We do not insist that it is the duty of all to sing. We think rather that it is the duty of some persons not to attempt to sing in public worship. Such are the incurable in voice and ear. But, at the same time, far more persons than now attempt to sing, may, can, and ought to qualify themselves for an edifying use of their voices in praising God in his courts. And, before we too soon conclude against choirs, as the cause of the disuse of congregational singing, a little inquiry into the habits of the people, in regard to this matter, may disclose a reason or two, which make greatly against some of those who complain of the evil. In the first place, is it not a fact that people generally do not pay sufficient regard to the excellent recommendation in the Directory [for Worship], (chap. 4, sec. 2,) to “cultivate some knowledge of the rules of music, that we may praise God in a becoming manner, with our voices, as well as our hearts!” What can be expected from indolence on this point, but the dissonant marring of “becoming praise,” which no man has a right to produce, or an unseemly silence, which no man has a right to relapse into, until he has made a fair, but fruitless effort to learn to sing. Secondly, let us inquire how much of this evil is to be attributed to another evil probably lying back of it: is there not reason to believe that singing in family worship has fallen into general desuetude? Where this exercise is neglected, not only does family worship lose one of its sweetest elements and attractions, with all its soothing and elevating influences, but the young are deprived of one of the most likely and important means and aids for acquiring the taste, the practice, and the skill, which fit them to join in the praises of the Lord’s house, with advantage to themselves and others. The operation of these two causes appears to us to be so obvious, that they need only to be indicated in order to suggest the remedy. On this point, proper care must be exercised by pastors, elders, and heads of families. Let them co-operate in promoting the cultivation of sacred music in families, in singing schools, in Sunday schools, in singing meetings, and even in the week-day schools; and let the officers of the church take the supervision both of the instruction of their people, and especially the youth, and of the whole department of the singing in public worship. Thus, much will be done to correct any undue innovations by precentors and choirs, and to secure that co-operation of choir and people which is most desirable and practicable. This combination is attainable in entire consistency with a style of church music, such as is demanded by the dignity of the service and approved by good taste, and with the edification of the people and the greater glory of God. Otherwise, it may well be feared that the work of “praising God in his sanctuary” will be monopolized by a very few persons; and it will be no sufficient apology for the indolent worshipper, that he is ready to objurgate “singing by Committee,” and “praising God by proxy,” while, in contrast with his own remissness, the zeal and pains which strive to rescue the singing of God’s praise from utter neglect and contempt, are worthy of all commendation.

These observations are all that the Committee deem it expedient, at this time, and in this form, to suggest to the notice of the Assembly and of the Church.

In bringing them to a close they have, according to their best judgment, fulfilled the only trust expressly confided to them by the last General Assembly.

And here, it would, perhaps, become them to rest.

The Committee however will take the liberty of making some further report with reference to the second point contained in the overture from the Synod of Philadelphia.

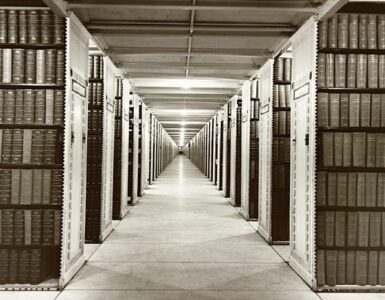

Although the act of the Assembly, appointing this Committee, conferred upon it no power to prepare a book of tunes, yet, in view of the overture, and of an apparently general expectation that the Committee would come to some practical conclusion on this point, the subject was considered as fully as their circumstances permitted, and resulted in the selection of a considerable number of sacred melodies adapted to our book of Psalms and Hymns. A list of the titles by which these tunes are commonly known, will be laid before the Assembly, in an appendix to this report.

It may be stated here that the minds of several members of the Committee strongly doubted the expediency of adding a new book to the scores now in circulation.—Nevertheless, it was determined that a collection of sacred tunes, especially adapted to our book of Psalms and Hymns, prepared with such knowledge of our own people as might more intelligently reflect the best usages of the various sections of our Church, and meet the real wants of this communion, without pandering to a mean or corrupt taste, and embracing, in one volume, the approved melodies which arc now scattered through many books, inaccessible to a large number of our churches; the whole arranged with their appropriate harmonies, by the best available scientific ability, was desirable in itself, and might receive the approbation of the Assembly, and prove acceptable to the churches of our communion. It was resolved, therefore, to make the attempt.

In anticipation of the meeting of the Committee, a notice was published, requesting all competent persons, especially in the Presbyterian Church, to forward to the Committee their views on this subject, and also a list of tunes approved and in use, in their respective localities. This request was responded to extensively, and not only was the information thus obtained by the Committee valuable to their deliberations, but it revealed a very agreeable harmony in regard to the character of the tunes recommended, and a far higher standard than had been previously supposed to exist.

The principles by which the Committee were guided, in making the compilation now submitted to the judgment of the Assembly, are such as the following:

First: To restore and preserve old standard tunes, and, as far as practicable, in their original forms, both as to air and harmony.

Second: To select from more recent compositions, such as had been approved by trial in many places, or might be suitably introduced into all their churches.

Third: To insert some tunes which appeared to be favorites in some considerable sections of the Church, notwithstanding some fastidiousness on the part of the Committee with respect to them. They desired not to forget that they were making provision for the edification of a large community of various tastes. While they desired to insert only music of such a character as might elevate and improve the standard of taste throughout the Church, they did not feel at liberty, even while they rejected some tunes which were suggested to them from abroad, as well as some suggested by members of the Committee, to discard such as, after all, might be approved by a better judgment than their own, especially such as were endeared by long and hallowed association, and would be extensively and painfully missed from the collection.

Fourth: To provide tunes for all the various meters of our Psalms and Hymns, and in suitable proportion as to their respective numbers and the various character of the words. And also to illustrate the tunes by words selected from our own psalmody.

Fifth: To provide a sufficient body of sacred music of such various style and character, that the collection might serve for all ordinary purposes, especially for Sunday schools, families, social worship, and congregations, as these various exigencies may require.

The number of tunes embraced by the list herewith submitted is about four hundred. It may appear, on revision, that such a number is too great; or, further consideration may demand the exclusion of a portion, and the insertion of others in their stead, so that the number finally approved may be still as great had the Committee inserted everything suggested to them, the collection would have been nearly twice as large. Hence, they selected what appeared to their unanimous judgment to be best, most approved, and most likely to be useful. The mass of the rejected were such as, in their judgment, were unsuitable, would be missed, if at all, by few, and better displaced by others of a more chaste and elevated character, and at the same time, no less melodious, simple, and easy to be sung.

Sixth: It is proposed to add an appropriate selection of set pieces for special occasions, such as Anthems and Chants, both metrical and prose, adapted to our psalmody, and also to portions of the common prose version of the book of Psalms, and other inspired lyrics from the Old and New Testaments. This selection is not yet completed.

Should this work be prosecuted to completion, and be approved by the Assembly, and recommended to the churches, the Committee believe that it will be of advantage in these respects:

First: It will embody in one volume of convenient size, a collection of tunes, the most approved and in use among our churches—to the greater part of which, very few individual churches have access at present.

Second: It may be enlarged, if hereafter that should appear desirable, by an Appendix or Supplement, without displacing the book or disturbing it in any manner.

Third: It would serve to produce, to a very considerable extent, that uniformity in the praises of our Church, as a whole, which cannot but be thought desirable.

Fourth: It will promote congregational singing, and prevent its disuse, which, in part, at least, arises from the frequent change of books and introduction of new tunes, many of which never become known and domesticated in our public worship.

Fifth: It will be an appropriate accompaniment to our authorized book of Psalms and Hymns—prepared as it will have been with reference to that book throughout, and to the state of our churches. It may be too, that such a work as this may aid in promoting the more general use of that book in all our congregations.

In reporting progress thus far, it is to be observed that the work is by no means finished. Beside the revision and completion of the selections, there remains the whole labor of preparing the book for press. To this end, the harmonies must all be subjected to careful examination by competent professional skill—words are to be wedded to the music—fair copies are to be written out for compositors—proof sheets are to be read. In some cases, copyrights in new music are to be compensated;—and, in short, the whole work of editing must be provided for; and this will necessarily involve considerable expense, independent of the mere outlay for printing and publishing.

The Committee respectfully suggest to the General Assembly, that this report, and the appendix, be referred to a special committee of their body for examination; and if, thereupon, the Assembly should approve and encourage the further prosecution of this work, on the basis of the principles herein set forth, that authority be given to this Committee, as in the case of the Book of Psalms and Hymns, (see Minutes of the General Assembly, A. D. 1842, pp. 44, 45,) to complete the work and make the necessary arrangements for its publication and circulation among our churches.

Please visit the Presbyterians of the Past homepage and see the topical selections included in the recently updated “Notes & News” collection. Older entries no longer available on the homepage can be accessed in the “Notes & News Archive.”