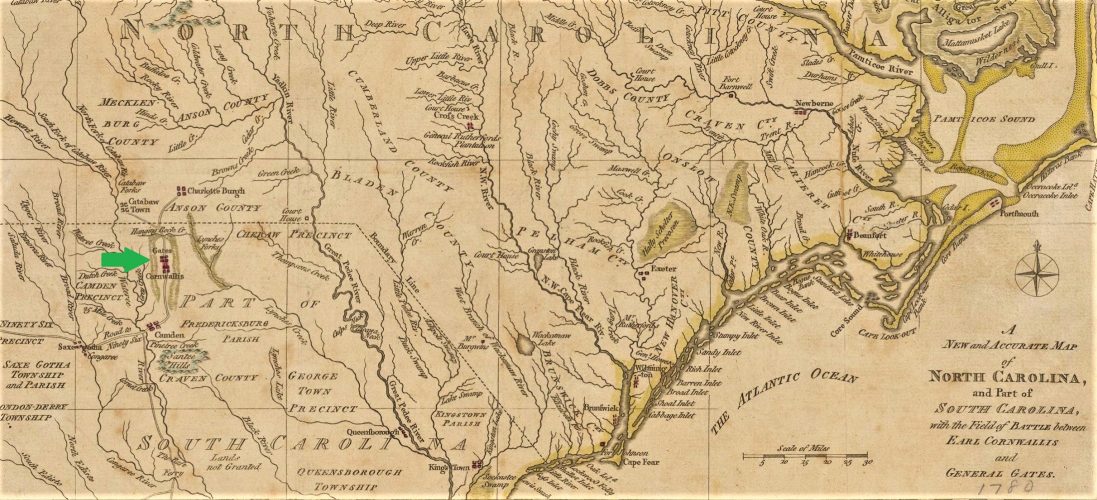

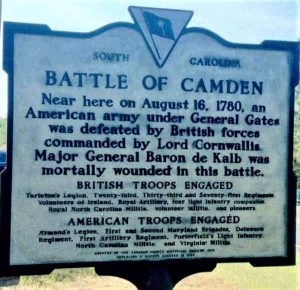

Chaplain Armstrong made his way to North Carolina with the Second Maryland marching nearly 500 miles from Philadelphia to camp at Wilcox’s Ironworks just south of what is currently Siler City. He wrote William Churchill Houston, July 8, 1780, relating the complaints of his portable parish concerning the pittance of meat and a shortage of horses. A month later the food situation worsened as the troops camped at the ferry landing beside the Peedee River just east of the current town of Ansonville. The men had two days beef to stretch into seven days protein and no meal nor flour. Armstrong observed that their diet dwindled to just apples. He commented “it is impossible for human nature to have subsisted so long as I have known it to upon green fruit.” Despite Armstrong’s assessment that “everything discouraging dwells around our little army,” he was nevertheless optimistic, “We have not much, I believe, to fear from the enemy, but troops must be more or less than men who can long endure what we now suffer.” He was incorrect about not fearing the enemy because when Armstrong and his associates went into South Carolina it turned out some fear was warranted. On August 16, 1780 roughly 3,000 soldiers including the Second Maryland and Chaplain Armstrong under Continental commander Gen. Horatio Gates were defeated by the British in the Battle of Camden. Historians have attributed the defeat to Gates’s poor strategy and failure to heed the advice of the previous commander, Gen. Baron Johann de Kalb (killed at Camden). This humiliating rout was added to the devastating captures of the port cities of Savannah in the fall, then Charleston in May. John Hall’s account (see Notes) has no correspondence from Armstrong regarding Camden, whether this is because Armstrong did not write to Houston, or because Hall chose not to include an account of the costly defeat is not noted. However, the American forces would rebound to turn the Revolution in the South towards the ultimate success Armstrong anticipated with victories at King’s Mountain in October and Cowpens in January 1781.

Chaplain Armstrong made his way to North Carolina with the Second Maryland marching nearly 500 miles from Philadelphia to camp at Wilcox’s Ironworks just south of what is currently Siler City. He wrote William Churchill Houston, July 8, 1780, relating the complaints of his portable parish concerning the pittance of meat and a shortage of horses. A month later the food situation worsened as the troops camped at the ferry landing beside the Peedee River just east of the current town of Ansonville. The men had two days beef to stretch into seven days protein and no meal nor flour. Armstrong observed that their diet dwindled to just apples. He commented “it is impossible for human nature to have subsisted so long as I have known it to upon green fruit.” Despite Armstrong’s assessment that “everything discouraging dwells around our little army,” he was nevertheless optimistic, “We have not much, I believe, to fear from the enemy, but troops must be more or less than men who can long endure what we now suffer.” He was incorrect about not fearing the enemy because when Armstrong and his associates went into South Carolina it turned out some fear was warranted. On August 16, 1780 roughly 3,000 soldiers including the Second Maryland and Chaplain Armstrong under Continental commander Gen. Horatio Gates were defeated by the British in the Battle of Camden. Historians have attributed the defeat to Gates’s poor strategy and failure to heed the advice of the previous commander, Gen. Baron Johann de Kalb (killed at Camden). This humiliating rout was added to the devastating captures of the port cities of Savannah in the fall, then Charleston in May. John Hall’s account (see Notes) has no correspondence from Armstrong regarding Camden, whether this is because Armstrong did not write to Houston, or because Hall chose not to include an account of the costly defeat is not noted. However, the American forces would rebound to turn the Revolution in the South towards the ultimate success Armstrong anticipated with victories at King’s Mountain in October and Cowpens in January 1781.

James Francis Armstrong’s ancestors were from Ireland and knew well what it was like living under British rule. He was born in West Nottingham, Maryland, April 3, 1750. His father was named Francis, but his mother’s name could not be found in the sources. Francis was a ruling elder in the West Nottingham Presbyterian Church. His early education began in the academy established by Robert Smith in Pequea, Pennsylvania, but he finished studies in the school mastered by John Blair that had been established by his brother Samuel at Fagg’s Manor.

In the fall of 1771, Armstrong entered the junior class of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) and roomed in the home of its president, John Witherspoon. He completed the program in 1773 and at commencement he was one of three participants debating the statement, “Every human Art is not only consistent with true Religion, but receives its highest improvement from it” (Craven, 263). Of the class of thirty-one graduates, nearly all had a part in the Revolutionary War whether as chaplains, military personnel, physicians, merchants, or in government. The impressive class included future physicians John Witherspoon Jr. and Hugh Hodge, the father of Princeton Seminary professor Charles. Future state governors included Virginia’s Henry Lee, Jr. who may be remembered more for his military prowess as Light Horse Harry during the Revolution; New York’s Morgan Lewis was also a jurist who served on the state supreme court; and New Jersey’s Aaron Ogden added to his service as governor representing his state in the U. S. Senate. Among the thirteen graduates joining Armstrong in the Presbyterian ministry were two of Robert Smith’s sons, John Blair and William Richmond; future Virginia educator William Graham who would establish Liberty Hall Academy in Lexington; John McKnight would be selected moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in 1795; and local church Pastor Samuel Waugh would serve the Silver Spring congregation in Carlisle Presbytery for twenty-five years. Historians have mentioned how influential eighteenth-century Princeton was for the founding and development of the United States, but even so, Armstrong’s class was quite impressive. If they ever had a reunion, it would have been an event.

The Presbyterian Seminary at Princeton would not be established until 1812, so Armstrong was tutored in theology by President Witherspoon . He received the best education possible for a student concerned to govern his doctrine and ministry by the Westminster Standards. On June 6, 1776, he was taken under care of the Presbytery of New Brunswick as a candidate for the ministry in a meeting at Princeton with only three ministers and one elder present. Sparse attendance may have been due to political and social instability as the move for independence would come to fruition in less than a month with the Declaration of Independence. During the Revolution the Presbyterians faced challenges holding judicatory meetings and it affected Armstrong’s progress towards ordination. The Presbyterian concern for a plurality of elders and connectional polity to accomplish ministries of common interest and adjudication was more difficult to achieve during war than episcopal or congregational polities which primarily govern by the few or locally. For licensure, the presbytery assigned him 1 Timothy 1:15 for exegesis with his emphasis to be De Veritate Christianae Religionis (The Truth of the Christian Religion). He sustained the examinations and was required to preach Romans 12:2.

And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.

It would have been an interesting exposition because the British were landing, and the nation was being turned upside down by the Revolution. How do transformed minds prove the truth of God during death, devastation, and dire needs created by war? How is war the “perfect will of God?” But Armstrong’s licensure would not proceed as planned. The next meeting of New Brunswick Presbytery was scheduled to convene at Shrewsbury near the New Jersey coast, but because of the British presence the meeting could not be held resulting in postponement of his licensure. In this crisis, John Witherspoon wrote to the Presbytery of Newcastle and sent documentation of Armstrong’s qualifications with the hope the judicatory would license him. Newcastle Presbytery was selected because Armstrong’s home church was within its bounds of spiritual oversight and its bounds were not so near the British. The plan worked, he was transferred, and licensed to preach in January 1777. Congress appointed him a chaplain for the Second Maryland Brigade, July 17. He was ordained to that end by Newcastle Presbytery, January 14, 1778, in Pequea, Pennsylvania, with the sermon delivered by his former mentor, Robert Smith. When the ordination was reported to the Synod of New York and Philadelphia that year it was said in the synod minutes that he was ordained sine titulo, without call, but this conclusion was drawn without the New Castle records in hand for review. Difficulties created by the war may have caused the misunderstanding with ways of transit blocked and concerns about political stability leading people to relocate inland or stay home. None the less, the next year the issue was resolved when the Synod met.

It would have been an interesting exposition because the British were landing, and the nation was being turned upside down by the Revolution. How do transformed minds prove the truth of God during death, devastation, and dire needs created by war? How is war the “perfect will of God?” But Armstrong’s licensure would not proceed as planned. The next meeting of New Brunswick Presbytery was scheduled to convene at Shrewsbury near the New Jersey coast, but because of the British presence the meeting could not be held resulting in postponement of his licensure. In this crisis, John Witherspoon wrote to the Presbytery of Newcastle and sent documentation of Armstrong’s qualifications with the hope the judicatory would license him. Newcastle Presbytery was selected because Armstrong’s home church was within its bounds of spiritual oversight and its bounds were not so near the British. The plan worked, he was transferred, and licensed to preach in January 1777. Congress appointed him a chaplain for the Second Maryland Brigade, July 17. He was ordained to that end by Newcastle Presbytery, January 14, 1778, in Pequea, Pennsylvania, with the sermon delivered by his former mentor, Robert Smith. When the ordination was reported to the Synod of New York and Philadelphia that year it was said in the synod minutes that he was ordained sine titulo, without call, but this conclusion was drawn without the New Castle records in hand for review. Difficulties created by the war may have caused the misunderstanding with ways of transit blocked and concerns about political stability leading people to relocate inland or stay home. None the less, the next year the issue was resolved when the Synod met.

By the report now made by the New Castle Presbytery, it appears, that there was a mistake in the report of last year, respecting Mr. Armstrong’s Ordination; that he was not ordained sine titulo; but in consequence of his having accepted a Chaplaincy in the Army. (Klett, 563)

Chaplain Armstrong continued serving the soldiers until after General Lord Cornwallis surrendered his troops to George Washington at Yorktown in 1781. An unwanted souvenir of his chaplaincy from the time in the Carolinas was a disease he described as a rheumatic affliction. This disease would plague him for the rest of his life. According to Craven, Armstrong continued ministry with the military until early in 1782 as indicated by a payroll record (p. 264).

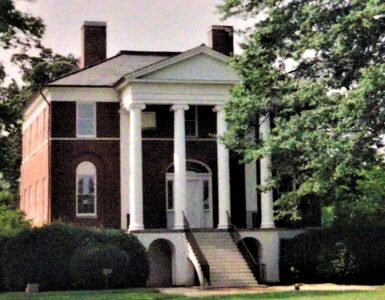

In June 1782, he began supplying the Presbyterian Church in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, continuing until “he was compelled to discontinue his labors on account of an enfeebled state of health, occasioned by an attack of the measles” (Sprague). In August he married Susannah Livingstone with the wedding conducted by his close friend John Witherspoon. But he struggled to locate a church for ministry until late 1784 when First Church in Trenton became vacant because of the death of its minister Elihu Spencer for whom Armstrong delivered the funeral sermon. He supplied the church until 1787 when he accepted its call issued in April. In addition to Trenton, he served the church in Lawrenceville, 1790-1806.

One of Armstrong’s connectional duties during his ministry was as moderator of the General Assembly. When the judicatory convened in First Church, Philadelphia, May 17, 1804, it was called to order by retiring moderator James Hall who delivered his sermon from Romans 10:1.

Brethren, my heart’s desire and prayer to God for Israel is, that they might be saved.

Armstrong assigned Ashbel Green and Mr. Ebenezer Hazard to take the historical resources held by the Stated Clerk and write “a complete history of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America” and the presbyteries and congregations were “strictly enjoined” to do all they could to complete their histories and forward them to the authors (Minutes, p. 287). It was reported that the Synod of the Carolinas had seven presbyteries—Orange, First Presbytery of South Carolina, Second Presbytery of South Carolina, Concord, Hopewell, Union, and Greenville (p. 292). David Rice of the Presbytery of Transylvania (Kentucky) sent a letter referred to a committee requesting “the advice of this Assembly respecting the licensure of persons to preach or exhort, who have not received a liberal education” (p. 293). This letter cut to a key issue in the day which was ministerial education. The issue led to the founding of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church which reduced requirements for study and confessional fidelity. Also from Kentucky was a letter signed by James Blythe, John Lyle, and Robert Stuart who constituted a committee of West Lexington Presbytery appealing to the Assembly for healing the breach in the Synod of Kentucky. These appeals from Rice and West Lexington were indicative of the problem in Kentucky as revivalism seen in meetings such as those at Cane Ridge influenced many to believe they were called to preach, but they were not educated according to Presbyterian standards, nor did they hold to the Calvinism of the Westminster Standards. The letter was made order of the day for the next day. A letter from Dr. George Buist of Second Church, Charleston, on behalf of the Presbytery of Charleston asked for the presbytery to be a member of the Assembly without membership in the Synod of the Carolinas. It seems an odd request, but it may have been motivated by the isolation of the Low Country from the mass of Presbyterians in the Midlands and Upstate and the locations selected for synod meetings. The Assembly responded that it would be willing to hear the request if it was submitted properly, but this willingness does not mean the request would necessarily be granted. The committee appointed by the 1803 Assembly to consider publishing a new edition of “the Confession of Faith” (Note the minutes often use this term to refer to the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church which includes not only the Confession but all the Westminster Standards and the Book of Discipline; it can be confusing, so context is important). The report was tabled to be taken up Friday morning. The committee appointed to handle David Rice’s inquiry submitted the draught of a two-page letter it believed should be sent to him. The letter was adopted. It said that changing the educational requirements requires constitutional revision, but the Assembly believed that catechists like the “catechists of the primitive church, may, under proper restrictions and limitations, be usefully employed in instructing the young in the principles of our holy religion, and conducting the praying and voluntary societies of private Christians” (p. 301). This seems to the current writer a practice itself that would necessitate constitutional revision, so maybe this motivated Amzi Armstrong, George Potts, James Inglis, and Robert Cooper to dissent against catechists. The letter was signed by Moderator Armstrong and sent to David Rice. The committee’s report on revising the Confession of Faith (Constitution of the Presbyterian Church) was adopted, but it rejected revision of the Westminster Standards and proposed fourteen amendments to the Form of Government. An index was also suggested to facilitate use of The Constitution. Once the constitutional procedures were accomplished for revision, the new edition would be published in 1806 in Philadelphia by Jane Aitken who inherited her father Robert’s printing shop. Another issue coming before Armstrong was one James Gaston, a member of a church in the Synod of Pittsburgh who married his deceased wife’s sister’s daughter. The Assembly had previously made deliverances for other near-kin marriages, and in this case said “no absolute rule can be enjoined” but instead it left the case to

the discretion of the inferior judicatories under their care, to act according to their own best lights, and the circumstances in which they find themselves placed. (p. 306)

The Assembly continued with additional discussion of the problems in Kentucky that it resolved with a pastoral letter extending just over three pages. The missions report was extensive and included the appointment of several missionaries to go west in the frontier and build the church. A request from the Presbytery of Baltimore asking for the Assembly to meet within its bounds was rejected.

That as a co-operation by and between the General Assembly, the Committee of Missions, and the incorporated Trustees of the Assembly, appears to be conducive to the interests of the church, and as the members of the Committee of Missions, and those of the Board of Trustees, generally reside in Philadelphia, and can only hold their sessions there, the Assembly cannot at this time comply with the request. (Minutes, p. 317)

So, a reason why from 1789 to 1837 the Assembly met 44 out of 49 times in Philadelphia (see Moderators page introduction), is explained by this resolution. How would this go over if the PCA always met in Atlanta, and the OPC met exclusively in Philadelphia? Probably not very well. Moderator Armstrong adjourned the Assembly May 30th after fourteen days including two Sabbaths when sessions were not held. Statistics show 190 ministers with calls, 40 without, 33 licentiates, 204 vacant churches, 5 synods, and 24 presbyteries; total membership was not given. It would have been good if some of the ministers without calls could have been lined up with vacant churches. James Armstrong must have been a tired man, especially given his health problems.

He continued in Trenton for twenty-nine years with the church providing an assistant his last year because increased affliction from the rheumatic disease weakened him and he could not preach. James Francis Armstrong died January 19, 1816. Samuel Miller of Princeton Theological Seminary delivered the sermon at his funeral. Susannah and James had six children, five of whom survived him. Susannah received a military pension for his chaplain service beginning in 1836 and she died at 93 in 1851. They are both buried in Riverview Cemetery in Trenton.

While at the College of New Jersey Armstrong was a member of the American Whig Society. The College of New Jersey granted him the A. M. in 1781. He was an original member and the second secretary, 1790-1797, of The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey, which was founded in 1783. He was on the board of the College of New Jersey from 1790 until his death. Six sermons of his are included in, Light to My Path: Sermons by the Rev. James F. Armstrong, Revolutionary Chaplain, ed. Marian B. McLeod, A Bicentennial Publication, Trenton: First Presbyterian Church, 1976.

Barry Waugh

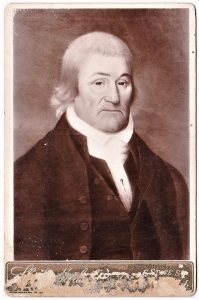

Notes—The map in the header is from the New York Public Library Digital Collection and is titled, “A new and Accurate Map of North Carolina and Part of South Carolina: with the Field of Battle between Earl Cornwallis and General Gates,” it is dated 1780; the green arrow shows the location of the Battle of Camden. For further information about near-kin marriages in the Presbyterian Church download the PDF dissertation on the Log College Press site The History of a Confessional Sentence, 2002, which studies the relevant sentence in the Westminster Confession, chapter 24, “Of Marriage and Divorce.” See, Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution, 1775-1783, Maryland Historical Society, 1900, page 294. The historical marker picture is from the site, “American Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783.” The portrait appears to be a cabinet card photograph which would have been taken long after Armstrong’s death. The image used here is from the Find A Grave entry for Armstrong and its identity is confirmed by McLeod in the Armstrong sermon collection mentioned in this post. The photo is of a painting made by an unknown artist. John Hall, History of the Presbyterian Church in Trenton, N. J.: From the First Settlement of the Town, New York, 1859, 480 pages; the quotes in the first paragraph above are from pages 304-5. Craven refers to Princetonians 1769-1775: A Biographical Dictionary, ed. Richard A Harrison, entry by W. Frank Craven, Princeton UP, 1980. Walter Edgar, Partisans and Redcoats: The Southern Conflict that Turned the Tide of the American Revolution, 2001; this book provides a good overview of the importance of South Carolina’s contributions to achieving independence. Brief Sketches of the New Jersey Chaplains in the Continental Army, by Frederic R. Brace, 1909; Armstrong pages 8-9. Klett refers to Guy S. Klett, Minutes of the Presbyterian Church in America 1706-1788, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society, 1976; note that the first General Assembly was in 1789 so Klett’s book includes minutes from the first presbytery meeting in 1706 through the Synod of New York and Philadelphia. The minutes used for Armstrong’s work as moderator is Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its Organization A. D. 1789 to A. D. 1820 inclusive, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, [n.d.].