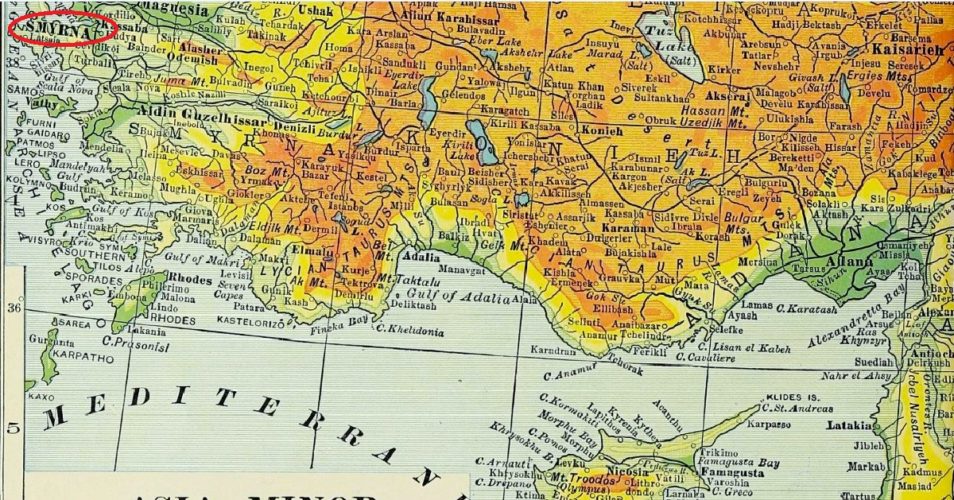

Smyrna was located about thirty miles north of Ephesus situated at the point of a vee-shaped inlet where the city of Izmir is in modern Turkey. It was a significant port at the time of Polycarp and was possibly the greatest city within the Roman province of Asia. The climate could be pleasant because a wind would blow from the Aegean Sea into Smyrna from early afternoon into the evening. A contemporary of Polycarp named Aristides described the breeze as having an aroma like a fresh grove of trees. Smyrna was a key city of eastern Christianity having one of the seven churches addressed by the Lord in the book of Revelation. His message was one of encouragement to the congregation because they would face persecution (Rev 2:8-11). Smyrna with possibly as many as 100,000 residents is where Polycarp lived and ministered.

He was taught as a young man by the Apostle John. Polycarp’s only extant writing is Epistle to the Philippians (circa 125) which was sent by himself and “the elders (πρεσβύτεροι) who are with him” to “the church of Philippi.” It was a response to a letter from the Philippians asking him to forward some letters to the Syrian Church, and they requested that copies of some epistles by Ignatius be sent to Philippi. Polycarp’s Philippians is important for the New Testament because he quotes or alludes to passages in the gospels as well as epistles by Paul, Peter, and John, which shows that by early in the second century their writings were accepted as the Word of God. He also provides instruction to both the deacons and presbyters (πρεσβύτεροι) of the church.

One debate occurring during Polycarp’s life involved the date for celebrating Easter. The Quartodecimans (Fourteeners) lived primarily in Asia Minor, and they had a different way for determining the day for remembering the resurrection each year. They believed Easter should occur on the fourteenth day of the Jewish month of Nisan to parallel the Passover (Lev 23:5). One can see how this view would arise given the week of Jesus’ passion occurred at the time of Passover, but the Anti-Quartodecimans thought that setting the date for Easter using the Jewish calendar was wrong. Pope Victor (189-199) would overrule the Quartodecimans but they nevertheless continued their practice with waning influence as the years passed. In 325 the Council of Nicea (First Ecumenical Council) directed that all the churches follow the practice of having Easter the first Sunday after, not on, the Paschal or first moon, which is the first full moon on or after the spring equinox. This formula was built on astronomy but there are other factors contributing to determining the date (see article cited in the notes at the end of this article).

How does this calendar controversy relate to Polycarp? He was sympathetic to the Quartodeciman view, and it is not difficult to understand its attraction given the determinative principle came from the practice of Passover that foreshadowed Christ’s sacrifice.

But it was not Polycarp’s teaching regarding church offices, the importance of Philippians for history of the New Testament canon, nor the Quartodeciman controversy that keeps him in historical remembrance, it is his death. Polycarp was martyred February 23, 155 (dates vary) at the instigation of both Gentiles and Jews as they appealed to the Roman magistrate. His last hours and death are recounted in Letter of the Smyrnaeans on the Martyrdom of Polycarp. He was persecuted for being a Christian, and Christians were called atheists by the Romans because they would not worship the pagan deities. When the Roman magistrate pressed Polycarp concerning his atheism, imploring him to give in, he responded,

Fourscore and six years have I been His servant, and He has done me no wrong. How then can I blaspheme my King who saved me?

Polycarp came from a covenant household and was a Christian all his 86 years—God had never done him wrong. It is a remarkable affirmation because when challenging times come, the tendency is to blame God for the troubles. In times of struggle thoughts like, “Everything was going so well, but you let me down God,” or, “It just isn’t fair God, it’s just not fair” might come to mind. Notice also that Polycarp calls God the King, showing clearly that Caesar is not his lord. Polycarp would be burned at the stake shortly after making this statement. The stake was a horrible way to die, nevertheless Polycarp could say the Lord had “done me no wrong” even in the face of a terrible execution. How many times do believers say the Lord does not care about their suffering from sickness, economic hardships, wayward children, apathetic parents, irresponsible political leaders, or seemingly impossible challenges on the job? God could change things readily, but the great purpose for his people is they be sanctified a holy nation that glorifies and enjoys him more fully. As James says, “the testing of your faith produces steadfastness,” and growth in steadfastness leads to becoming “perfect and complete, lacking in nothing” (1:3-4). Polycarp’s affirmation was not an impulse of the moment fed by an instantaneous infusion of faith, but it was instead the result of a covenant home, instruction by the Apostle John as a young man, and continued growth in sanctification. He persevered devotedly affirming Christ in the face of opposition that resulted in his execution.

In the West, as things are now, the possibility of facing death for the gospel could be at the threshold. Events of recent years have proved how rapidly things can change. The Martyrdom of Polycarp is extrabiblical literature that reminds modern readers of the dangers faced by their spiritual ancestors from centuries ago. It would be good to display Polycarp’s affirmation in a prominent place so it can be read daily. It is good to be reminded often that the Lord never does his people wrong no matter how dire circumstance may appear, he governs by providence working all things together for his glory and the Church’s good.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The map is from Funk & Wagnall’s 1923 Atlas of the World and Gazetteer on Internet Archive. On catholic.com more information about the complexities of setting the day for Easter is provided in the article “How are the Dates for Easter, Palm Sunday, and Ash Wednesday Determined?” For Polycarp’s writings I used Vol. 2 (Part II) of The Apostolic Fathers, S. Ignatius, S. Polycarp, edited by J. B. Lightfoot, London: Macmillan, 1889; J. B. (Joseph Barber) Lightfoot (1828-1889) is thorough and provides the Greek texts with translations and notes that include rendering πρεσβύτεροι as elders (Lightfoot was an Anglican). B.B. Warfield said of Lightfoot in his review of Apostolic Fathers published in The Presbyterian &Reformed Review 1891, 2:8, p. 692, that he was “the greatest Patristic scholar of the England of our generation.” For a thorough study of Polycarp see, Polycarp’s Epistle to the Philippians and the Martyrdom of Polycarp, Introduction, Text, and Commentary, edited by Paul Hartog, Oxford University Press, 2013, about 400 pages in length; I note this book based on the review by H. H. Drake Williams, III, on themelios. The Greek interlinear New Testament that parallels with the ESV translates ὑπομονή(ν) as “endurance” in the interlinear but uses “steadfastness” in the ESV parallel text; “endurance” is more passive as though someone is putting up with something, while “steadfastness” is more active indicating persistence and perseverance.