Robert Jefferson Breckinridge was known theologically for his adherence to the Westminster Standards with Old School Presbyterian precision; politically for siding with the Union during the Civil War within a family including Southern sympathizers; as well as rhetorically for his skill lecturing about subjects of interest and persuasively preaching the Bible as a minister. He was not reluctant to engage his adversary whether intellectually or physically—he was dismissed from Princeton College for fighting and completed his education at Union College. Breckinridge was boldly opinionated in the press wielding his pen like a honed saber cutting to the heart of the opposition’s case whether he was writing for his own serials or others. Individuals in the public eye are assessed differently by their contemporaries with some showing admiration while others find them loathsome. One contemporary who seems an unlikely admirer was James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888).

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge was known theologically for his adherence to the Westminster Standards with Old School Presbyterian precision; politically for siding with the Union during the Civil War within a family including Southern sympathizers; as well as rhetorically for his skill lecturing about subjects of interest and persuasively preaching the Bible as a minister. He was not reluctant to engage his adversary whether intellectually or physically—he was dismissed from Princeton College for fighting and completed his education at Union College. Breckinridge was boldly opinionated in the press wielding his pen like a honed saber cutting to the heart of the opposition’s case whether he was writing for his own serials or others. Individuals in the public eye are assessed differently by their contemporaries with some showing admiration while others find them loathsome. One contemporary who seems an unlikely admirer was James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888).

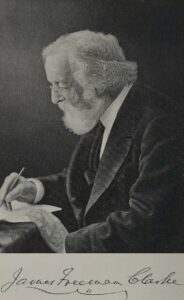

Clarke was a Unitarian minister, transcendentalist, and abolitionist whose education was achieved at Harvard University and Harvard Divinity School. Included among his friends were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., and Nathaniel Hawthorne. In Clarke’s collection, Memorial and Biographical Sketches, one of the individuals included is Breckinridge. Also remembered in the book are individuals holding views similar to those of Clarke such as Theodore Parker and William Ellery Channing, but other tributes include George Washington, William Shakespeare, and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Clarke and Breckinridge agreed on some points, but their theological, sociological, and political opinions were very different. For example, with respect to doctrine, Clarke thought points of theology gathered as a confession of necessary beliefs was divisive and unnecessary because what was most important was the advancement of man; but for Breckinridge, confessional Westminster orthodoxy was essential not only for righteousness but also for glorifying and enjoying God in worship and vocation.

Clarke was a Unitarian minister, transcendentalist, and abolitionist whose education was achieved at Harvard University and Harvard Divinity School. Included among his friends were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., and Nathaniel Hawthorne. In Clarke’s collection, Memorial and Biographical Sketches, one of the individuals included is Breckinridge. Also remembered in the book are individuals holding views similar to those of Clarke such as Theodore Parker and William Ellery Channing, but other tributes include George Washington, William Shakespeare, and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Clarke and Breckinridge agreed on some points, but their theological, sociological, and political opinions were very different. For example, with respect to doctrine, Clarke thought points of theology gathered as a confession of necessary beliefs was divisive and unnecessary because what was most important was the advancement of man; but for Breckinridge, confessional Westminster orthodoxy was essential not only for righteousness but also for glorifying and enjoying God in worship and vocation.

Since these two men differed so much, how did Clarke become familiar enough with Breckinridge to find points of admiration?

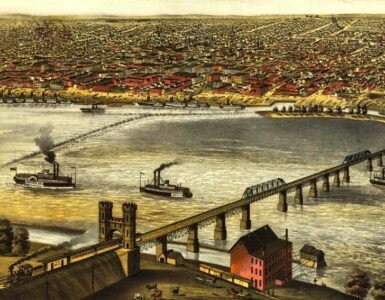

During Clarke’s call to First Unitarian Church in Louisville, Kentucky, he became acquainted with Breckinridge and heard him preach. He found Breckinridge admirable for his rhetorical ability, incredible memory, and opposition to slavery, however, he found his Calvinism detestable and thought the Old School-New School division was much ado about trivialities. All in all, Clarke was as objective towards Breckinridge as his Unitarian-transcendentalist presuppositions would allow him to be.

Not everyone found admirable qualities in Breckinridge. Isabella (Smyth) Fauntleroy was the sister of Thomas Smyth (1808-1873) who was pastor of Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston. She heard him preach and recounted her impressions of Breckinridge to her brother in a letter provided in Autobiographical Notes, Letters and Reflections by Thomas Smyth, D.D. Smyth and Breckinridge often held different views concerning issues in the church, so Mrs. Fauntleroy’s view of Breckinridge was clouded by sympathy for her brother. The sermon she heard was preached June 3, 1860 in a church near Chicago. She said,

Dr. R. J. Breckenridge [sic] preached here last Sabbath Day; I suppose his reputation is too well known for me to say anything to you about him, yet his feeble voice, want of teeth, and want of all the graces of an orator, caused a severe disappointment among the vast audience who had collected to hear him. I went up after service and had Mr. Bardwell introduce me to him as your sister, he said he saw a great likeness between us.—Spoke instantly of your article in the Review. Said no one had told him that it was yours, but that he recognized Thomas Smyth instantly in it, “Tell him” said he to me “when you write to him, that I see if he is an invalid, he is still able to do a great deal of mischief.”—He very pleasantly talked to Smyth [Isabella’s son], who was standing by, and he said “Madam, he is much better looking than his Uncle [Thomas Smyth].” (pages 557-58)

The “article in the Review” refers to Smyth’s “Theories of the Eldership” published in the Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review, April 1860. Breckinridge’s comment that Smyth was an invalid refers to a health problem he had all his life, which was debilitating, throbbing headaches. If Isabella’s opinions of Breckinridge were the only ones available, one might wonder how such an unimpressive man could have become such an important leader among Old School Presbyterians.

South Carolinian James H. Thornwell had a more generous opinion of Breckinridge. Thornwell was on his way to board ship for a trip to Europe when he stopped in Baltimore a few days pending sailing. At the time, Breckinridge was pastor of the city’s Second Church.

The next day, we came safely on, and on last Saturday, at about ten o’clock at night, we reached the city of Baltimore, where I now am. On Sunday morning I went to Brother Breckinridge’s church, and heard an excellent sermon. I went home with him, and have been staying with him ever since. The more I see of him, the more I love him. There is no man in the Church more misrepresented and more misunderstood. He is exceedingly affectionate, kind, and affable in his family, and among his people. He has some habits like my own. He loves to sleep in the morning, to smoke cigars, to sit up at night, and to tell funny stories. He is a very industrious and laborious man. Yesterday he made me write another article in reply to the Catholic priests, which will be published in the next Visitor [The Presbyterian Visitor]. He has furnished me with some very flattering letters to ministers in Europe, for which I am very much indebted to him. (to his wife, May 11, 1841, Palmer, Life, 159-60)

Is this the same man? He preached “an excellent sermon,” and he suffered from being “misrepresented and … misunderstood.” As their friendship developed the two corresponded often about issues facing Old School Presbyterians including discussions of the office of elder, the laying on of hands in ordination, and the question of boards for the direction of the denomination’s ministries. In these debates both Breckinridge and Thornwell sometimes had a common polemical adversary, Thomas Smyth.

In the transcription of Clarke’s memorial for Breckinridge that follows some comments have been included in brackets [ ] and full names have been given rather than just surnames for individuals that could be identified more fully.

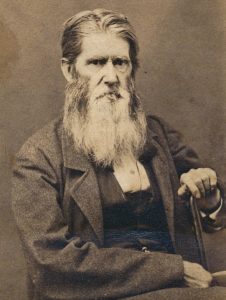

The header photograph was taken by the author and shows Henry David Thoreau’s 10′ x 15′ cabin as reconstructed at Walden Pond. The dark figure is a statue of Thoreau whose Walden; or, Life in the Woods, was published in 1854, the year after Breckinridge became a professor at Danville Theological Seminary. The portrait of aged Breckinridge is from a CDV held by the PCA Historical Center; the portrait of Clarke is from his autobiography via Wikipedia.

Regarding transcendentalism, the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says it was “Stimulated by English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume, the transcendentalists operated with the sense that a new era was at hand. They were critics of their contemporary society for its unthinking conformity, and urged that each person find, in Emerson’s words, ‘an original relation to the universe’. Emerson and Thoreau sought this relation in solitude amidst nature, and in their writing.” (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/transcendentalism/).

Reading the posts on this site, “R. J. Breckinridge 1800-1871,” and “A Belligerent D.D. Robert J. Breckinridge,” will provide some additional introductory information about him. R. J. Breckinridge was the maternal grandfather of B. B. Warfield, professor at Princeton Seminary.

Barry Waugh

ROBERT JEFFERSON BRECKINRIDGE.

WHEN, in 1836, Robert J. Breckinridge preached in Louisville, Kentucky, I thought him the best extempore preacher I had ever heard. Matter and manner were both simple and strong. It was like the direct, earnest conversation which one holds with you, on a subject of which his mind and heart are full. He never hesitated for a word, never repeated himself, but went on rapidly and easily from point to point, like Goethe’s star, “without haste and without rest.” There was little or no metaphor, few illustrations, and nothing of the ornate style and oratorical delivery that were very popular then in the West. Two favorite speakers, Mr. Maffitt and Mr. Bascom, had lately been preaching in the city and drew large crowds of admirers. Nothing could be more opposed to their florid style than his severe simplicity. It was a delight for me to listen to him, notwithstanding the vigor of his orthodoxy; and I thought it showed the good sense of the Kentuckians, that, though caught by the flowery grandiloquence of other speakers they yet regarded Mr. Breckinridge as one of their finest orators. It is evidence of good taste when one prefers the early English pointed architecture to the flamboyant style of later centuries.

And the Kentuckians in those days were good judges of public speaking. They did not read books, and had very little of the culture which derives from literature but they were passionately fond of good speech. They assembled in great numbers at political barbecues, where, under the shadows of the majestic beeches and tulip trees of the Kentucky forest, they spent long summer days hearing Whig and Democratic speakers discuss questions of public polity. At that time they had an opportunity of hearing both sides, and speakers of both parties spoke to both parties. Members of Congress were called upon to explain to their constituents their course in Congress, and must answer on the spot the most trying questions. This educated a race of stump speakers, of whom the tradition long lingered in Kentucky, men like the famous Joseph Hamilton Davies, prompt, clear, and confident, who could,

Bend, like perfect steel, to spring again and thrust.

And, among these ready speakers of his own day, Robert J. Breckinridge easily stood the chief, and was accounted the best stump-speaker in Kentucky.

Mr. Breckinridge and his brothers, John Breckinridge and William L. Breckinridge, were all originally lawyers and all afterward became Presbyterian ministers. The gift of fine extemporaneous speech belonged to all three. In John there was perhaps more of illustration and more appearance of emotion than Robert. Both were full of fire, but in John it appeared in lambent flames, while in Robert it was a central force, on which his whole nature rested. I once was listening to John Breckinridge, and as I sat directly in front of the pulpit he could not help seeing me, and knowing me no doubt as the Unitarian minister of the place, he took occasion to denounce all those who taught Unitarian doctrines as men “dripping with the blood of souls.” No doubt he believed it, and he, like his brothers, always had “the courage of his opinions.” But at a later time in New Orleans, visiting a dying lady, a relative of his own, and a warm Unitarian, finding that, notwithstanding her heresy, her faith in Christ was sincere and strong, the good man forgot his theology, and said, “If you feel so, cousin, I have nothing to say against your faith.” Robert J. Breckinridge was as brave as a lion, and his chivalric nature led him always to take part with the oppressed. A relative of his, an older man, told me this anecdote, which belongs to the years before he became a preacher. They were riding together on horseback, on their way to Frankfort, Kentucky, and as they approached the city they came up to a wagoner who was cruelly abusing a young negro. Mr. Breckinridge rode up to him, and asked him why he was treating him that way. The wagoner replied with a curse and threat, which, however, were no sooner out of his mouth than Mr. Breckinridge responded by administering to him a severe beating, cutting him about the face with his riding-whip, so that the ruffian ran, got on one of his horses, and rode away. Then my friend said to Mr. Breckinridge, “The fellow has got what he deserved, but it becomes us to go into Frankfort as soon as possible, for he has gone back to get that party of teamsters we passed half a mile back.” So, they rode on toward Frankfort but as they descended the long hills that surround the place, fast riding was difficult, for these hills are of limestone, lying in horizontal strata, which are outcropped, making the descent like a flight of steps. When about half-way down they heard a loud noise behind and found that half a dozen teamsters were coming on after them, full speed, in one of their wagons. Dangerous or not, they were obliged to ride down the hill at the same pace, and just succeeded in escaping their pursuers.

The same courage and energy were shown by Mr. Breckinridge, afterward, on a more important field. He, with Drs. George Junkin, William S. Plumer, George A. Baxter, and others, led the Old School party in the General Assembly when they cut off four Synods, containing some forty thousand members, a step that caused the disruption of the church. The pretext for cutting off these Synods was some alleged unconstitutionality in their original union [i.e., Plan of Union with New England Congregationalists, 1801]. But as they had remained in the church without objection for thirty-seven years, it is not likely they would have been removed if they had been considered as orthodox. But these New York and Ohio Synods were tainted with New School heresies. So, Mr. Breckinridge, a Calvinist genuine and sincere, if there ever was one, considered it necessary to save the church at all hazards from the poison of these heresies. Under his splendid captaincy the deed was done, and the victory was gained for Calvinism pure and simple.

But another generation has now come, which knows not Joseph. The interest in those severe discussions has died away, and many will wonder why such a vehement controversy should have raged around such abstract and purely metaphysical questions. The principal “error” of the New School men, and one which was denounced as being equivalent to “another gospel,” was this:

That God would have prevented the existence of sin in our world, but was not able, without destroying the moral agency of man; or, that for aught that appears in the Bible to the contrary, sin is incidental to any wise moral system.

The substance of the dispute was just at this point. The New School divines said that God would have prevented sin, but could not do it. The Old School said He could have prevented sin, but would not. But when the latter were asked why God would not, they gave the same answer as their opponents “Because God chose that man should be a free agent.” The only difference between the “Could nots” and “Would nots” therefore, was as to which phrase should come first in the statement. And on this point the church was divided.

But give due credit even to bigotry. These excommunicating chiefs were narrow, were one sided, were intolerant, but they were logical and sincere. When you once adopt the principle that any theological statement is essential to salvation, it is difficult to know where to stop. To draw the line between essentials and non-essentials is difficult; for to a logical mind every part of a system is essential to the integrity of the whole.

No doubt R. J. Breckinridge was a born fighter, a man of war from his youth. He snuffed the battle afar off, and rejoiced in the conflict. A sincere antislavery man, though born and raised in the midst of slaveholders, he remained true to his convictions when other men fell away, and the love of many waxed cold. I remember the time when all the leading men in Kentucky, Whigs and Democrats, with few exceptions, were opposed to slavery, and declared themselves in favor of amending the State Constitution by inserting an antislavery clause. But when a convention was called in the state to form a new Constitution, the great majority of these theoretical antislavery men were afraid to act. Not so Robert J. Breckinridge. During three long summer days he stood in front of the courthouse in Lexington, maintaining against all opponents that the interests of Kentucky, no less than its conscience, required the abolition of slavery. It was like a knightly tournament, only in a nobler cause, and fought with better weapons. He wrestled not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers of the darkness of this world, and spiritual wickedness in high places. Well would it have been for Kentucky if she had listened to that manly voice, and been led by that commanding eloquence. She then would have been the advanced fortress of the Free States during the war, and would not have been ravaged alternately by the opposing armies. She would not have seen her families divided, son against father, and brother fighting against brother. She would not have had that still worse record, that in the greatest conflict of the age for truth and freedom, she alone of all the States preferred to remain neutral.

In that great conflict, also, Robert J. Breckinridge was true to himself and his ideas. Amid the falling away on all sides, of those most near and dear, the old man stood by the flag of the Union. He saw his fields and home repeatedly ravaged by the Confederate troops; he saw disaster after disaster fall on the Union arms; he saw his old friends leaving him, but he remained firm and true to the end.

Among innumerable false, unmoved,

Unshaken, unseduced, unterrified,

His loyalty he kept, his love, his zeal;

Nor number, nor example, with him wrought.

To swerve from truth, or change his constant mind

Though single. From amidst them forth he passed,

Long way through hostile scorn, which he sustained,

Superior, nor of violence feared aught;

And with retorted scorn, his back he turned

On those proud towers to swift destruction doomed.

[Milton, “The Faithful Angel”]

Mr. Breckinridge was, as we have said, in some things narrow and intolerant. But he had a candid mind, and if convinced of an error was willing to acknowledge it if he saw good in an opponent, he was glad to admit it. In a journey through Europe, about the year 1836-7, he came to Geneva, and there became acquainted with the Venerable Company of Pastors, and heard them preach in the cathedral. He frankly confessed his “great surprise and sincere delight” in hearing the Scripture expounded “with clearness, truth, and fervor.” “I had, also,” he says, “the pleasure to make the acquaintance of two of the Venerable Company of Pastors, whose kindness deserved my thanks, as much as their intelligence excited my interest. And, in general, I think the lives of that body are, in private, blameless to a degree not common either in most established churches or decided errorists.”

One more little anecdote, which we heard in Western Pennsylvania. An elder of the Presbyterian church in the town of Butler wished one Saturday to go to Pittsburg on business of importance. The stage from Erie came through so full that he could not get a seat, but presently there followed an extra stage containing only one gentleman and two ladies. He asked permission of the gentleman to take a seat and was permitted to do so. As he rode on, he allowed his hand carelessly to drop on some flowers belonging to the ladies, which were in a pot beside him. This happened once or twice, notwithstanding the request of the original gentleman to the church elder, to be more cautious. At last, he said, “Sir ! I have permitted you to take a seat with us because you said you were anxious to reach Pittsburg, but you shall leave the stage if you touch those flowers again, even if I have to put you out my self.” This made a little “unpleasantness” for the rest of the journey. The elder did his business and then went to a friend’s house, who said “It is fortunate that you came to-day, for to morrow we have the celebrated Robert J. Breckinridge to preach for us” The elder went to church, and saw in the pulpit his stage-coach companion, and found that he had used his excellent opportunity for becoming well acquainted with Robert J. Breckinridge by making himself especially disagreeable to him.

Sleep peacefully in thy grave, good soldier of the cross. We who are fighting in another camp, to which thou wert not very friendly, can see and admire generous, brave, and honest qualities, and force of intellect and character, even in an opponent; and we lay this tribute on thy coffin : Sit tibi terra levis! [“May the earth rest lightly upon you.” Abbreviated on Roman memorials, S.T.T.L. and is a predecessor of “Rest in Peace” R.I.P.].