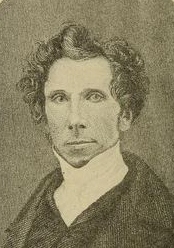

Thomas Smyth was born June 14, 1808 in Belfast, Ireland, the sixth son of Samuel and Ann Magee Smith. Thomas’s father was a grocer and an elder in the local Presbyterian Church. Later in Thomas’s life he adopted the “Smyth” spelling to avoid confusion with another Old School Presbyterian minister in the United States named Thomas who spelled his surname “Smith.” He graduated from Belfast College in 1829 after having completed his preparatory studies in the Academic Institute of Belfast which was associated with the college. He moved to America where he enrolled in the senior class at Princeton Seminary and completed his theological education in 1831.

Thomas Smyth was born June 14, 1808 in Belfast, Ireland, the sixth son of Samuel and Ann Magee Smith. Thomas’s father was a grocer and an elder in the local Presbyterian Church. Later in Thomas’s life he adopted the “Smyth” spelling to avoid confusion with another Old School Presbyterian minister in the United States named Thomas who spelled his surname “Smith.” He graduated from Belfast College in 1829 after having completed his preparatory studies in the Academic Institute of Belfast which was associated with the college. He moved to America where he enrolled in the senior class at Princeton Seminary and completed his theological education in 1831.

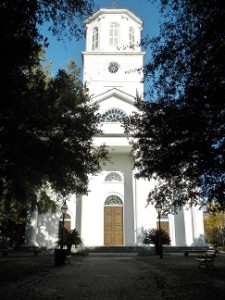

When Thomas was ordained by Newark Presbytery he was to go to Florida as a missionary, but he did not make it to Florida because he was requested as a pulpit supply for Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, South Carolina, in 1832. After completing the supply ministry he was offered a permanent call. The young minister was uncertain about remaining in Charleston but once his doubts were overcome he was installed the pastor in Dec. 1834.

Shortly after Rev. Smyth’s arrival in Charleston, he married Margaret Milligan Adger the daughter of James Adger who was a prosperous local businessman that made his sizeable fortune via Charleston’s harbor and its busy docks. Currently there are two cobble-stoned roads off of East Bay Street in Charleston, “North Adgers Wharf,” and “South Adgers Wharf,” which are reminders of the Adger era of Charleston shipping. Margaret and Thomas were married on July 9, 1832.

Shortly after Rev. Smyth’s arrival in Charleston, he married Margaret Milligan Adger the daughter of James Adger who was a prosperous local businessman that made his sizeable fortune via Charleston’s harbor and its busy docks. Currently there are two cobble-stoned roads off of East Bay Street in Charleston, “North Adgers Wharf,” and “South Adgers Wharf,” which are reminders of the Adger era of Charleston shipping. Margaret and Thomas were married on July 9, 1832.

Though Dr. Smyth was loved by his congregation, it does not mean they were happy with every aspect of his ministry. He had a habit of preaching too long, or so some in the congregation thought. In order to address this problem, a speaking tube was installed from the choir loft to the pulpit so the violinist could speak to Dr. Smyth and let him know he was preaching too long. Despite the warnings echoing through the sound tube’s horn so that they were loud enough for people in the front pews to hear them, he paid no attention and continued to proclaim the  Word at length. Another means of communicating the exasperation of some congregants with the length of Smyth’s sermons was one man throwing his hat in the aisle as a reminder to put a lid on it, but that hint did not work either.

Word at length. Another means of communicating the exasperation of some congregants with the length of Smyth’s sermons was one man throwing his hat in the aisle as a reminder to put a lid on it, but that hint did not work either.

As with many ministers, Thomas Smyth was afflicted with bibliomania. He wrote during an extended trip, “My thirst for books in London became rapacious. I overspent my supplies in procuring them at the cheap repositories and left myself in the cold winter for two or three months without a cent.” Smyth was experiencing bibliomania in a way that had been expressed earlier by Erasmus of Rotterdam. When Erasmus was studying Greek he wrote to Battus, “I have been applying my whole mind to the study of Greek; and as soon as I receive any money I shall first buy Greek authors, and afterwards some clothes.” Over the years, Smyth’s lust for books and just about anything else printed led to the accumulation of about 20,000 volumes. His compulsive book buying caused tension with his wife. In a letter in 1846, while they were constructing an addition to their house that would make room for more books, he was told to control his spending:

I tell you this now as a preface to a caution, not to involve yourself too deeply or inextricably in debt by the purchase of books & pictures; of the last, with the maps, we have enough now to cover all the walls, even of the new rooms; & the books are already too numerous for comfort in the Study & Library. … But I would enter a protest not only against books & pictures, but all other things not necessary & which can come under the charge of extravagance. Do be admonished & study to be economical.

It seems Mrs. Smyth was exasperated with her husband depleting the household funds with his book and document buying frenzies. However, as his health deteriorated, he made the decision to sell over half of his library to Columbia Theological Seminary. He was concerned that since he could not take full advantage of his books it would be best that students have access to the unique and valuable collection.

It seems Mrs. Smyth was exasperated with her husband depleting the household funds with his book and document buying frenzies. However, as his health deteriorated, he made the decision to sell over half of his library to Columbia Theological Seminary. He was concerned that since he could not take full advantage of his books it would be best that students have access to the unique and valuable collection.

Thomas Smyth was a persistent student even as his physical afflictions increased. Despite his physical problems, he was a prolific writer whose many publications would be compiled in ten thick volumes after his death. His weakness was such in the later years that at one point the church constructed a saddle-like seat for him to use as he preached from the pulpit. Headaches afflicted him so severely that he would stick his head in a bucket of ice water for relief. He continued to shepherd his sheep as he could, but he succumbed to his weakening flesh and died in Charleston on August 20, 1873. He had served his church for over forty years. He, Margaret, and several family members are buried in the churchyard of his first and only pastoral charge. Six of the Smyths’ nine children survived to become adults.

Barry Waugh

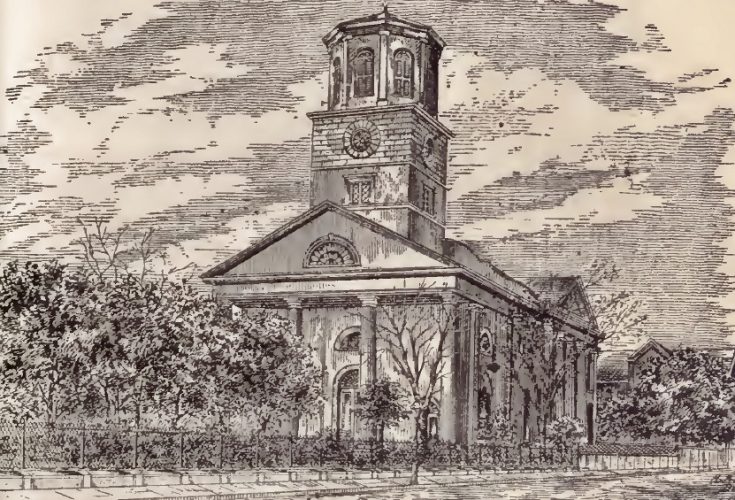

Notes–The header image of Second Church is from Charleston Illustrated, 1875, on Internet Archive. Thomas Smyth’s works were published in ten volumes. A free PDF index to the volumes is available on the PCA Historical Center website at this link. See also on Presbyterians of the Past the biography of Ellison A. Smyth, who was a son of Thomas and Margaret Smyth. The first time I encountered Erasmus’s often used quote it was on a bookstore bag and it read, roughly, “I buy books; if there is any money left, I buy food and clothes.” I wonder if Erasmus was living in tattered clothes because of a lust for books or was it because he wanted the books as tools for studying his real love, Greek.

Sources–This biography was edited and revised on August 21, 2015. The primary source used was Autobiographical Notes, Letters and Reflections, by Thomas Smyth, as edited by his granddaughter, Louisa Cheves Stoney, 1914. Erasmus’s quote was found in the translation of his letter to Battus of April 12, [1500], in The Epistles of Erasmus from His Earliest Letters to his Fifty-First Year Arranged in Order of Time, vol. 1, New York, 1901, as translated by F. M. Nichols, page 236. The photographs of the street sign, Second Church, and Smyth’s grave marker were taken by the author.