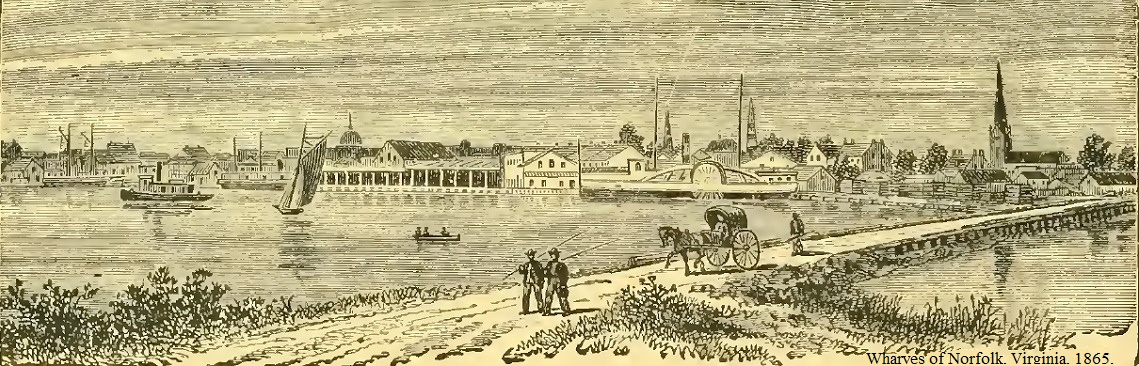

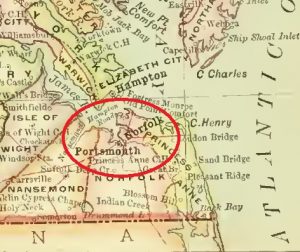

Epidemics resulting from diseases transmitted by mosquitoes cause people to be fearful. One of the most fearsome of these diseases is yellow fever, also called Yellow Jack, which was transmitted by mosquitoes when they attacked the residents of several cities near the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf Coast, and inland waterways of the United States. Between the 1793 epidemic in Philadelphia and the last recorded outbreak in New Orleans in 1905, other cities stricken–sometimes more than once–included New York, Boston, Baltimore, Savannah, St. Augustine, Memphis, Mobile, and in the Carolinas, Charleston and Wilmington. In 1855, Portsmouth and Norfolk which are across the Elizabeth River from each other in Virginia were devastated by an epidemic that robbed the two cities of about 3,000 of their combined population of roughly 23,000. At the time of the Yellow Jack plague, Rev. George D. Armstrong had been the minister of the First Presbyterian Church of Norfolk for about four years. He would minister to his congregation, to those of other denominations, and to many others afflicted and mourning residents of his city.

Epidemics resulting from diseases transmitted by mosquitoes cause people to be fearful. One of the most fearsome of these diseases is yellow fever, also called Yellow Jack, which was transmitted by mosquitoes when they attacked the residents of several cities near the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf Coast, and inland waterways of the United States. Between the 1793 epidemic in Philadelphia and the last recorded outbreak in New Orleans in 1905, other cities stricken–sometimes more than once–included New York, Boston, Baltimore, Savannah, St. Augustine, Memphis, Mobile, and in the Carolinas, Charleston and Wilmington. In 1855, Portsmouth and Norfolk which are across the Elizabeth River from each other in Virginia were devastated by an epidemic that robbed the two cities of about 3,000 of their combined population of roughly 23,000. At the time of the Yellow Jack plague, Rev. George D. Armstrong had been the minister of the First Presbyterian Church of Norfolk for about four years. He would minister to his congregation, to those of other denominations, and to many others afflicted and mourning residents of his city.

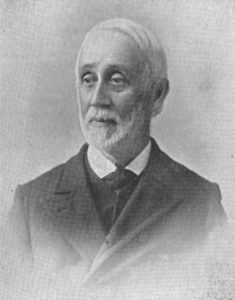

George Dodd was born to Rev. Amzi and Polly (Dodd) Armstrong in Mendham, New Jersey, in 1813. Amzi had taught school before his ordination in 1796 to serve the Presbyterian Church in Mendham where he would pastor for two decades. Though George grew up with a minister father, it appears his interests were in the sciences when he attended Princeton College and graduated in 1832. He moved to Richmond, Virginia, to live with his brother William who was the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church having succeeded John Holt Rice. While in Richmond George taught school for a living and was apparently influenced by his brother to become a minister. He continued teaching while he prepared for the ministry at near-by Union Theological Seminary completing his studies in 1837. Lexington Presbytery in the scenic Shenandoah Valley licensed him that fall to supply pulpits, and the following January he became Professor of Chemistry and Mechanics in Washington College at Lexington. It was at this time that he married Mehetable Hughes Porter in 1840. George was not ordained until 1843 when he was called by presbytery to be an evangelist with duties that included supplying the churches at Timber Ridge. Evangelist Armstrong continued to minister the Word and teach at Washington College until he accepted a pastoral call from First Presbyterian Church, Norfolk, Virginia, 1851.

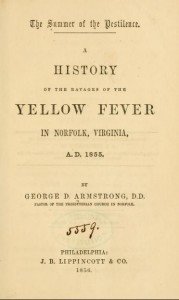

It was mentioned in the opening paragraph that after just a few years in Norfolk, Rev. Armstrong was faced with the challenges of ministry during a catastrophic epidemic of yellow fever. Armstrong’s first published book was The Summer of the Pestilence, 1856, which provided insight into his thoughts, concerns, and challenges during the epidemic. The first cases of yellow fever occurred about mid July 1855 in Portsmouth and the source of the contagion was believed to be a steamer from the island of St. Thomas. The citizens of Norfolk were fearful that the fever would be brought across the Elizabeth River from Portsmouth by way of the boat traffic between the cities. Their concerns were confirmed in short order when cases were diagnosed among the population. As the severity of the epidemic in both cities unfolded, Rev. Armstrong struggled with whether or not he should remain in the city or flee with those seeking safety. He decided to stay among his family, congregants, and Norfolk neighbors, but he would end up paying a price for the decision. Pastor Armstrong believed his steps were directed by God and as the yellow fever epidemic unfolded it would do so according to the Lord’s providence.

It was mentioned in the opening paragraph that after just a few years in Norfolk, Rev. Armstrong was faced with the challenges of ministry during a catastrophic epidemic of yellow fever. Armstrong’s first published book was The Summer of the Pestilence, 1856, which provided insight into his thoughts, concerns, and challenges during the epidemic. The first cases of yellow fever occurred about mid July 1855 in Portsmouth and the source of the contagion was believed to be a steamer from the island of St. Thomas. The citizens of Norfolk were fearful that the fever would be brought across the Elizabeth River from Portsmouth by way of the boat traffic between the cities. Their concerns were confirmed in short order when cases were diagnosed among the population. As the severity of the epidemic in both cities unfolded, Rev. Armstrong struggled with whether or not he should remain in the city or flee with those seeking safety. He decided to stay among his family, congregants, and Norfolk neighbors, but he would end up paying a price for the decision. Pastor Armstrong believed his steps were directed by God and as the yellow fever epidemic unfolded it would do so according to the Lord’s providence.

For myself, I can say that, in the prospect of the possible spread of the fever throughout our city, I have no anxious thought. The pestilence, when raging in its most terrible violence, and when man stands appalled before it, is yet ever under God’s control, and can claim no victims but such as are given it (p. 29).

By mid August, twenty of the sixty reported cases had resulted in death, and by the last week of the month Armstrong’s congregation lost its first member to the pestilence, Edmund James, who was Armstrong’s nephew. Whole households of First Presbyterian Church, those of other congregations, and others without a church were sick with the fever. On the Lord’s Day of September 2, Armstrong reported that the individuals attending First Church, which was one of the three  largest of his denomination in Virginia, numbered but 27 out of a communicant membership of 296. As the days of September passed, the mortality rate increased. Writing on Wednesday, September 12, Armstrong commented that he was regularly burying one or more members of his flock daily. The situation became so distressing that when he awakened in the morning he would ask himself, “Whom have I to bury today?” The Armstrong’s eldest daughter, twelve-year-old Mary, was stricken with the fever, but then enjoyed some recovery only to die late in September when the fever renewed its attack. The dignity of personal funeral services could no longer be allowed in many cases because sufficient coffins were not available, and the fear of other diseases arising from decaying bodies led to the use of mass graves. On one particular day a gravedigger told Rev. Armstrong that he had over ninety caskets to bury, but this was not the full extent of the yellow fever deaths because the number did not include the Roman Catholics whose remains were interred in their own cemetery. Every where one turned in Norfolk and Portsmouth there were coffins awaiting remains and others bearing bodies awaiting burial. At the docks were coffins awaiting use stacked on the decks of steamers coming from Baltimore. A person looking down the streets of Norfolk could see caskets hauled in the beds of wagons, others stacked by the doors of hospitals, and still more at the cemetery awaiting burial. Even Rev. Armstrong was afflicted with Yellow Jack at one point, but he survived to continue his ministry. But his family did not fare so well. Not only Edmund and lovely Mary died, but also his wife Mehetable and her sister Hatty Potter. Two younger children, Cornelia and Grace, were very sick with the fever but recovered and would live to become adults. The new cases of yellow fever reported waned so that by the second week of November there were two deaths. The signs that the disease was abating prompted Armstrong to have a worship service in his church for the first time in several weeks. Even though the epidemic was coming to an end, he noticed considerable evidence of its toll as he looked out over the congregation. There were only three families gathered before him not wearing mourning attire and in every part of the church “there were vacant seats, which called up to memory the forms of those who once occupied them” (p. 157). There was also a special area of the church where about sixty children between the ages of two and fourteen were seated together having been orphaned by the pestilence. Some of the children were found alive in their homes next to their recently deceased mother or father. How does a seminary prepare ministerial students to shepherd their flocks and bring the gospel to the lost during a time of catastrophic wholesale death?

largest of his denomination in Virginia, numbered but 27 out of a communicant membership of 296. As the days of September passed, the mortality rate increased. Writing on Wednesday, September 12, Armstrong commented that he was regularly burying one or more members of his flock daily. The situation became so distressing that when he awakened in the morning he would ask himself, “Whom have I to bury today?” The Armstrong’s eldest daughter, twelve-year-old Mary, was stricken with the fever, but then enjoyed some recovery only to die late in September when the fever renewed its attack. The dignity of personal funeral services could no longer be allowed in many cases because sufficient coffins were not available, and the fear of other diseases arising from decaying bodies led to the use of mass graves. On one particular day a gravedigger told Rev. Armstrong that he had over ninety caskets to bury, but this was not the full extent of the yellow fever deaths because the number did not include the Roman Catholics whose remains were interred in their own cemetery. Every where one turned in Norfolk and Portsmouth there were coffins awaiting remains and others bearing bodies awaiting burial. At the docks were coffins awaiting use stacked on the decks of steamers coming from Baltimore. A person looking down the streets of Norfolk could see caskets hauled in the beds of wagons, others stacked by the doors of hospitals, and still more at the cemetery awaiting burial. Even Rev. Armstrong was afflicted with Yellow Jack at one point, but he survived to continue his ministry. But his family did not fare so well. Not only Edmund and lovely Mary died, but also his wife Mehetable and her sister Hatty Potter. Two younger children, Cornelia and Grace, were very sick with the fever but recovered and would live to become adults. The new cases of yellow fever reported waned so that by the second week of November there were two deaths. The signs that the disease was abating prompted Armstrong to have a worship service in his church for the first time in several weeks. Even though the epidemic was coming to an end, he noticed considerable evidence of its toll as he looked out over the congregation. There were only three families gathered before him not wearing mourning attire and in every part of the church “there were vacant seats, which called up to memory the forms of those who once occupied them” (p. 157). There was also a special area of the church where about sixty children between the ages of two and fourteen were seated together having been orphaned by the pestilence. Some of the children were found alive in their homes next to their recently deceased mother or father. How does a seminary prepare ministerial students to shepherd their flocks and bring the gospel to the lost during a time of catastrophic wholesale death?

After the epidemic, Armstrong continued in what would be his one and only call as a full-time minister. He married Lucretia Nash Reid of Norfolk in 1857. When the Civil War began he was a chaplain for the Confederacy. Forty years of ministry to his flock and visiting ministry to other churches within the area contributed to the establishment of several new congregations. He was an active participant in the church courts, though he was not honored by serving as the moderator of a general assembly meeting. Armstrong was recognized for his literary work with an honorary doctorate from the College of William and Mary, 1854, and then with the LL.D. given by Washington and Lee, 1886. In 1891, when he retired from active ministry at First Church, Dr. Armstrong was honored with a special celebration that was led by ministers from the local churches including Moses D. Hoge of Second Presbyterian Church, Richmond.

George Dodd Armstrong, D.D., LL.D., died in Norfolk May 11, 1899. His ministry as pastor and citizen was recounted in his lengthy front-page obituary in Norfolk’s Virginian-Pilot for Friday, May 12. He was buried in Elmwood Cemetery and inscribed on his obelisk is the verse, “For I determined not to know anything among you save Jesus Christ and Him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2).

Dr. Armstrong continued writing after the publication of The Summer of the Pestilence in 1856. A few of his title are, Doctrine of Baptisms, 1857, Theology of Christian Experience, 1860, The Sacraments of the New Testament, 1861, and The Two Books of Nature and Revelation Collated, 1886. Supporting continued slavery he wrote, The Christian Doctrine of Slavery, New York and Norfolk: Charles Scribner, 1857; as well as with Cortlandt Van Rensselaer, Slaveholding and Colonization: A Reply to George D. Armstrong, D.D., of Norfolk, Va., on Slaveholding and Colonization, Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1858. The two authors also appear in Presbyterian Views on Slaveholding: Letters and Rejoinders to George D. Armstrong, D.D., of Norfolk, Va., Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1858. Van Rensselaer was editor of The Presbyterian Magazine where slavery was debated then the letters were reissued in these two and other titles. His shorter works include Study of Natural Science as a Means of Intellectual Culture, 1841, The Lesson of the Pestilence: A Discourse Preached in the Presbyterian Church, Norfolk, Virginia, Dec. 2, 1855, Politics and the Pulpit, 1856, Historical Discourse of Twenty-Five Years’ Ministry in the First Church, Norfolk, Virginia, 1876, and The Higher Criticism and its Conclusions-Three Discourses Preached in the First Presbyterian Church, Norfolk, Va., 1884. Included in The Presbyterian Quarterly of October 1888 was his article, “The Pentateuch Story of Creation,” on pages 345-368.

Barry Waugh

Notes–The header shows the wharves of Norfolk circa 1865. The portrait of Armstrong was provided by Wayne Sparkman, director of the P.C.A. Historical Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Some sources say G. D. Armstrong’s mother’s name was Mary and one mentions that Polly was her nickname. The brother that George lived with in Richmond, William, drowned in Long Island Sound in 1846. A history of Armstrong’s church in Norfolk is available under the title, The Church on the Elizabeth River: A Memorial of the Two Hundred and Tenth Anniversary of the First Presbyterian Church of Norfolk, VA. 1682-1892, Richmond: Whittet and Shepperson. I have spared readers the grizzly symptoms of the horrible disease that is yellow fever which the Spanish called vómito negro because victims’ vomit was black. The map showing the Norfolk-Portsmouth region is from, Appleton’s Atlas of the United States, New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1888. The populations of Norfolk and Portsmouth used were from the 1850 census as tallied on www.census.gov.