Foreign missions began with the ministry of the twelve apostles and their colleagues. Whether it was Paul, Timothy, or Peter, the Gospel was a message to be taken to other lands. The New Testament provides several accounts of the sufferings and hazards survived by Paul as he travelled the Roman Empire to evangelize its residents. Some fields of ministry were friendlier to the good-news messengers than others. Missions in the nineteenth century was likewise hazardous with challenges varying from field to field. Key problems faced included climatic hardships, wars, diseases, and of course, translation of the Bible into a language that had to be learned well by the missionary. There was also religious opposition encountered by the missionaries such as Nestorianism. Nestorius lived in the fifth century and was the bishop of Constantinople. He taught the divine and human natures of Christ were in fact two separate persons rather than hypostatically united natures constituting one person. His teaching was condemned by the council of Ephesus in 431. These as well as other challenges often discouraged workers enough that they returned to the United States after a year or two. Whether the field was South America, Africa, Asia, or the Middle East, ministry was difficult. The work of John H. Morrison in India and John and Rebecca Peale in China provide examples of the troubles faced as those called to foreign missions persevered on their fields of service. However, this post on Presbyterians of the Past is not only about missionaries, but one who was converted by God’s grace to work with a mission, and her name is Shushan Wright.

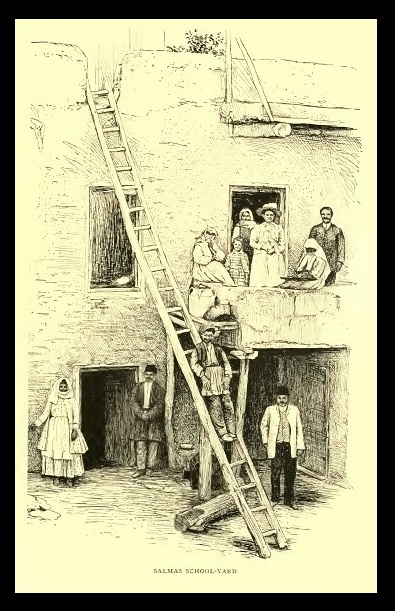

Information about Shushan’s life begins with her death. She was repeatedly stabbed in Oola, Salmas, in western Persia by a man on May 14, 1890 resulting in her death June 1. The assailant, Minas, was an Armenian whose religious background was likely the Armenian Church. Minas was a teacher in the mission school where Shushan served with her husband, American Presbyterian missionary Rev. John N. Wright. His first wife had died from a disease. Minas had been repeatedly rebuked by the Wrights in the past for his continued romantic interest in their house keeper and nanny, Asli. One night when Shushan checked on her child sleeping in Asli’s room she found that the nurse had left the baby alone. It was determined that she was meeting with Minas, which resulted in his dismissal from the school by Rev. Wright. Later, Minas went to the Wrights to obtain his final wages and transportation fare to return to his homeland. When Rev. Wright left the room to get the money, Minas attacked Shushan. He seized the opportunity, pulled a knife from his sleeve, and stabbed her several times. During the two days that passed before medical assistance arrived from Tabriz, Rev. Wright and J. C. Mechlin–director of the mission station, managed to stitch her wounds and make her as comfortable as possible. For a time it seemed she would recover and survive, but then her condition took a turn for the worse. More than two weeks after the assault, Mrs. Wright and her unborn son died on June 1.

Information about Shushan’s life begins with her death. She was repeatedly stabbed in Oola, Salmas, in western Persia by a man on May 14, 1890 resulting in her death June 1. The assailant, Minas, was an Armenian whose religious background was likely the Armenian Church. Minas was a teacher in the mission school where Shushan served with her husband, American Presbyterian missionary Rev. John N. Wright. His first wife had died from a disease. Minas had been repeatedly rebuked by the Wrights in the past for his continued romantic interest in their house keeper and nanny, Asli. One night when Shushan checked on her child sleeping in Asli’s room she found that the nurse had left the baby alone. It was determined that she was meeting with Minas, which resulted in his dismissal from the school by Rev. Wright. Later, Minas went to the Wrights to obtain his final wages and transportation fare to return to his homeland. When Rev. Wright left the room to get the money, Minas attacked Shushan. He seized the opportunity, pulled a knife from his sleeve, and stabbed her several times. During the two days that passed before medical assistance arrived from Tabriz, Rev. Wright and J. C. Mechlin–director of the mission station, managed to stitch her wounds and make her as comfortable as possible. For a time it seemed she would recover and survive, but then her condition took a turn for the worse. More than two weeks after the assault, Mrs. Wright and her unborn son died on June 1.

By means of the prompt services of the Honorable E. Spencer Pratt, who was the United States minister to Persia, and Col. C. E. Stewart, the English consul-general at Tabriz, Minas was arrested. He was from Ooroomeeyah which is in the historically disputed area in northwestern Iran close to Turkey and Syria. The death of Shushan and her son made the murder a double homicide according to the law of Persia. After the persistent efforts of English Consul General Stewart and United States Minister Pratt, Minas was brought to trial. He was charged, first, with having wounded Shushan severely resulting in her death; then secondly, with having caused the death of her unborn child. The night before Shushan was murdered, Minas had planned to use a revolver to kill her and Rev. Wright but because of unfavorable circumstances for success, he abandoned the plan. The law of the land was the death penalty for such crimes and both the British and American representatives believed Minas would die for the killing, but he was instead imprisoned for life. The murder, arrest, trial, and imprisonment of Minas led to increased concerns for personal safety not only for the missionaries, but also for other Westerners as religious and ethnic tensions once again came to the fore and threatened stability in the region.

Much of the information about Shushan Wright’s earlier life is found in William Rankin’s Memorials of Foreign Missionaries of the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., 1895. The full text of the tribute by Rev. B. Labaree, D.D., of the Presbyterian Western Persia mission is provided.

Much of the information about Shushan Wright’s earlier life is found in William Rankin’s Memorials of Foreign Missionaries of the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., 1895. The full text of the tribute by Rev. B. Labaree, D.D., of the Presbyterian Western Persia mission is provided.

The death of Mrs. Wright, of Salmas, has given us a terrible shock, one we shall not soon recover from. Under any circumstances her loss would have filled us with sorrow; but the terrible crime by which her life has been sacrificed has intensified our grief immeasurably.

Mrs. Wright was the daughter of Kasha and Sawa Oshana; the former was for many years a preacher in Koordistan and at times a highly esteemed teacher in our college, while Sawa was one of the first of Miss Fiske’s pupils, and has ever been one of our most devoted and beloved Christian sisters. Shushan, as we used to call her by her sweet Syriac name, spent much of her early life in the wild mountains of Koordistan, where she breathed in the free mountain air, the spirit of self-reliance, and independence so characteristic of the mountain Nestorians; however, in her case through wise parental training and the influence of divine grace she was brought under excellent control.

I shall never forget a journey I made with her family and a large party of missionaries and native preachers through the mountains towards Ooroomeeyah. She was then almost a grown woman, as full of life and grace as a bird, fearless, active, and agile over those terrible roads, while in the midst of dangers from robbers, both Christian and Koordish. When our camp was assailed by our own Nestorian muleteers and our equipment seized with the most angry display of firearms, Shushan flew swiftly up the mountain side after them, fought them, and as others of our party joined in the efforts to calm the angry men, she wrestled a gun from one of the men and brought it to the camp. We learned to admire her bravery and finesse on this tour as we never could have done in her home or her school.

Mrs. Wright had been in our female seminary [general education for women] from time to time and showed considerable aptitude for acquiring learning and culture. Later on she became a teacher in an orphanage conducted by some English ladies here, and later still was an assistant to the mission’s school for girls in Tabriz. She won to a great degree the love and confidence of those with whom she associated. We rejoiced in her as one of the choicest fruits of divine training through mission teaching.

In the year 1885 she was married to Rev. J. N. Wright of Ohio, his second wife, and they settled in Salmas where she took great interest in the missionary work. In the year 1888 she accompanied her husband to America, and only returned last fall. All who have known her since her return testify to her growing interest and activity in the Master’s cause. As far as the care of her little family would permit, she was assiduous in holding meetings for the women, visiting their families, teaching a Bible class each Sabbath, etc. The native pastor of the Oolah Church is warm in his commendation of her helpful influence during the months before her death.

During Mrs. Wright’s time of suffering from her wounds as she laid dying from the wanton, unprovoked assault upon her life, she showed a wonderful degree of fortitude and patience, and at the same time a most sweet and forgiving spirit in regard to her assailant. “If I die,” she remarked one day, “I shall go to heaven; but if he dies his soul is lost forever.” Her Christian character shone out brightly to the last. We can well believe that her remark to Mrs. Shedd, who visited her on her way through Salmas, was true, “All is light about me.”

Barry Waugh

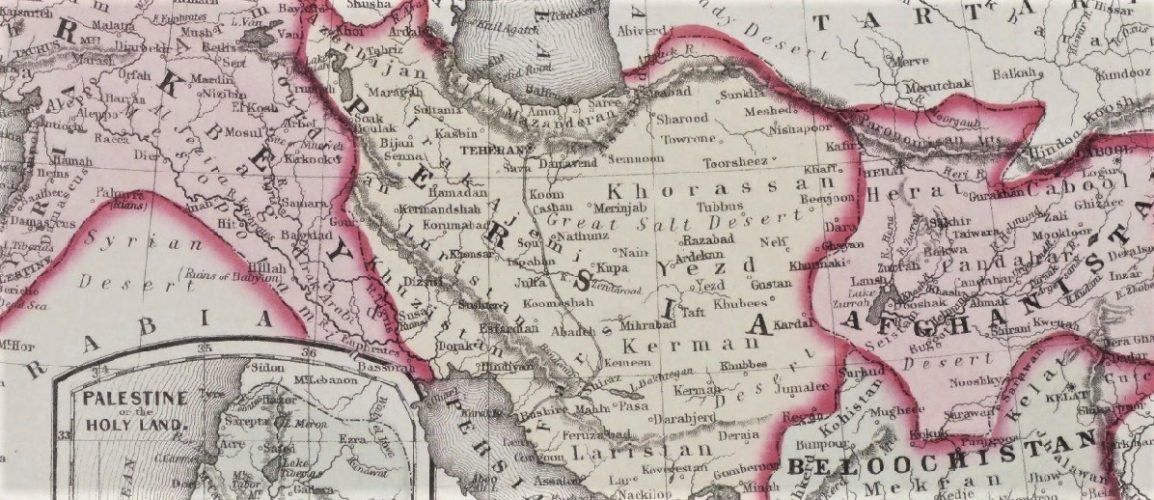

Notes—The header is from the University of Alberta as on Internet Archive and is titled “Map of Persia, Turkey in Asia, Afghanistan, Beloochistan, 1872.” The spellings of “Ooroomeeyah” include, Orūmīyeh, Urmia, Oroomiah, or Urūmiyeh, and probably other versions show Western speakers’ difficulties with transliterating the Eastern languages. The “Mrs. Shedd” referred to in the biography was not the wife of W. G. T. Shedd, but of Rev. J. H. Shedd, D.D. Rev. Wright’s first wife, Mary Letitia, was from Oregon, and she died of typhoid fever in Tabriz in 1878. Persia’s current name, Iran, came into use in 1935. Other than the source provided in the biography, another source used was the 35 page report of the murder of Shushan to United States Secretary of State James G. Blaine, which includes correspondence between Spencer Pratt of the United States, English Consul-General Col. C. E. Stewart, and others, along with testimony from the trial that includes Rev. Wright’s account of the events when his wife was attacked. There is also some interesting discussion of the murder of the unborn son and his inclusion as a victim in the case against Minas. The report is found in, United States Department of State, The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1890-91, With Index, In Thirty-Eight Volumes, Vol. 1, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891, pages 658-692. A publication that is interesting is Isaac Malek Yonan’s, Persian Women: A Sketch of Woman’s Life From the Cradle to the Grave, and Missionary Work Among Them, With Illustrations, Nashville: Cumberland Presbyterian Publishing House, 1898; in the preface, the author refers to several other publications regarding Persian women, customs, and culture. According to Yonan, page 139, there were about 150,000 Nestorians in Persia in his day with a fifth of them living in Ooroomeeyah. The article, The Modern Chaldeans and Nestorians, and the Study of Syriac among Them, by Gabriel Oussani, in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 22 (1901), pages 79-96, provides further information about the Nestorians.