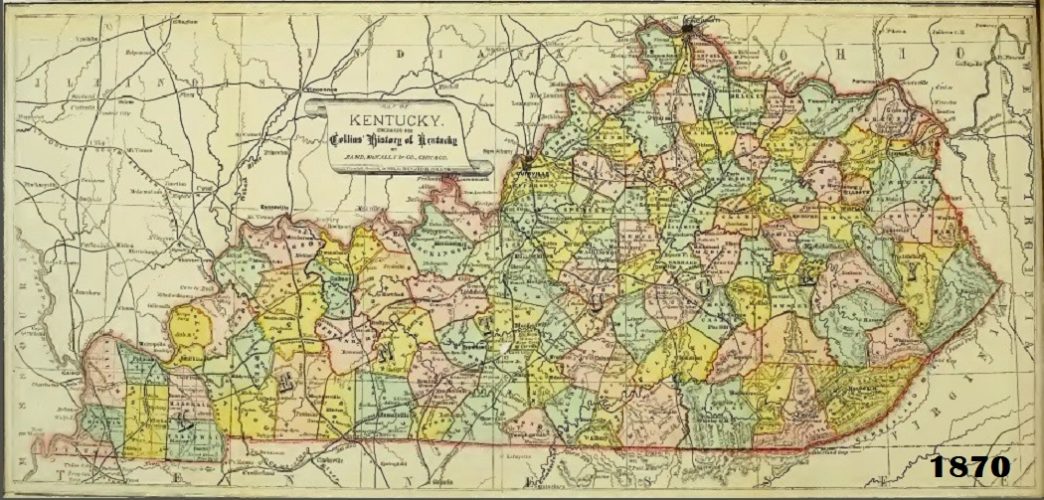

Nathan Lewis was born December 29, 1807 in Garrard County, Kentucky, to Gabriel and Phebe (Garrett) Rice. The family lived on a farm where the household struggled as did many rural families to make ends meet. Nathan began teaching school when he was sixteen years old to raise money for college tuition. At first, he wanted to become a lawyer, but his plans changed shortly after he became a Christian at the age of eighteen in Harmony Presbyterian Church. Despite his struggle raising sufficient funds, he showed his independent tenacity to make his own way when he refused financial assistance from his brothers. He chose Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, for his studies and matriculated in the fall of 1824. The college president was a frontiersman minister named Gideon Blackburn who was a colorful character. His ministry included several years in remote areas of eastern Tennessee where he preached with a musket by his pulpit. Rice took to his studies diligently while his empty pockets necessitated earning money by teaching Latin in his college during the day and then he studied at night.

Nathan Lewis was born December 29, 1807 in Garrard County, Kentucky, to Gabriel and Phebe (Garrett) Rice. The family lived on a farm where the household struggled as did many rural families to make ends meet. Nathan began teaching school when he was sixteen years old to raise money for college tuition. At first, he wanted to become a lawyer, but his plans changed shortly after he became a Christian at the age of eighteen in Harmony Presbyterian Church. Despite his struggle raising sufficient funds, he showed his independent tenacity to make his own way when he refused financial assistance from his brothers. He chose Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, for his studies and matriculated in the fall of 1824. The college president was a frontiersman minister named Gideon Blackburn who was a colorful character. His ministry included several years in remote areas of eastern Tennessee where he preached with a musket by his pulpit. Rice took to his studies diligently while his empty pockets necessitated earning money by teaching Latin in his college during the day and then he studied at night.

While continuing to live in Danville, N. L. Rice studied theology for about a year with Gideon Blackburn. In order to test his ministerial skills he was licensed to preach by Transylvania Presbytery on October 4, 1828. The following January he was called to pastor his home congregation but declined because he wanted to study more theology, so he moved from his frontier home to New Jersey where he began classes in Princeton Seminary in the fall of 1829. His class numbered forty-one students including his brother, John Jay Rice, and two South Carolinians who would teach in Columbia Theological Seminary, John Bailey Adger and Charles C. Jones. During his divinity program he married on October 3, 1832, Catherine who was the eldest daughter of the Rev. James K. Burch.

With his certificate of completion from Princeton Seminary in hand, Rice returned to Kentucky to pastor the church in Bardstown. He was ordained and installed on June 8, 1833. As was so often the case with ministers in frontier and rural areas, the locals looked to Rice to provide schooling for their children. An academy for girls and another for boys were established adding school master to his ministerial duties. The media of the day was the newspaper and Rice added publishing to his work when he established The Western Protestant, which eventually merged with another paper to become The Presbyterian Herald of Louisville. He served in Bardstown until his pastoral relation was dissolved on April 8, 1841.

Pastor Rice was dismissed by his presbytery to the Presbytery of Ebenezer where his call included work as a home missionary and the stated supply for the church in Paris, Kentucky.

As his ministry developed, Rice became increasingly involved in controversy and polemics regarding doctrine. During his years in Paris he debated Alexander Campbell in 1843 on the subjects of baptism, sanctification, and the use of creeds. Campbell’s ideas on the subjects were contrary to Presbyterian teaching. Further, he believed the simplicity of the first century church had been corrupted with denominational structures and bureaucracy. The growth of Campbell’s influence in Kentucky and his argumentation against Presbyterian doctrine appealed to Rice’s concern to defend the Bible’s teaching as expressed in the Westminster Standards.

In the twenty-first century it may be difficult to understand the appeal of public speaking in earlier times. Churches were often attended not only by Christians but also those seeking Sunday morning entertainment by listening to see whether the preacher would deliver a rhetorical masterpiece from the pulpit or instead stumble along miserably. Others would wander in and sit in the back of the church or the balcony and laugh at or bait the minister. Deacons were assigned to act as bouncers removing the disorderly visitors that interfered with the worship of God. Debates were another type of speaking entertainment, so, when they were announced crowds gathered. Some listeners expected to hear oratorical magnificence, see knock-down and drag-out verbal assault, have some laughs, and in the extreme, hoot and throw debris at the speakers. Just because the speakers were ministers did not exclude them from the whims of those who became restless or indignant. It was not always easy to be an interested listener.

In the twenty-first century it may be difficult to understand the appeal of public speaking in earlier times. Churches were often attended not only by Christians but also those seeking Sunday morning entertainment by listening to see whether the preacher would deliver a rhetorical masterpiece from the pulpit or instead stumble along miserably. Others would wander in and sit in the back of the church or the balcony and laugh at or bait the minister. Deacons were assigned to act as bouncers removing the disorderly visitors that interfered with the worship of God. Debates were another type of speaking entertainment, so, when they were announced crowds gathered. Some listeners expected to hear oratorical magnificence, see knock-down and drag-out verbal assault, have some laughs, and in the extreme, hoot and throw debris at the speakers. Just because the speakers were ministers did not exclude them from the whims of those who became restless or indignant. It was not always easy to be an interested listener.

Planning for the Rice-Alexander debate was considerable. It took place in Lexington. The convener was Kentucky’s Kentuckian, U.S. Senator, Congressman, and soon to be Whig Party candidate for the White House, Henry Clay. Each debater selected a moderator in the spirit of fairness with turns being taken wielding the gavel. Rice’s choice for moderator was former U.S. Congressman and Chief Justice of Kentucky George Robertson, while Campbell’s man was former U.S. Congressman and standing Kentucky Congressman John Speed Smith. Why the political figures were selected to govern a theology debate is not noted, but the organizers of the debate may have thought politicians were sufficiently disinterested in theology to not show favoritism. Each day of the debate followed the schedule agreed upon by the opponents. Monday through Saturday, no Sabbath debating, Rice and Campbell were to exchange comments for four hours beginning at ten in the morning. There were also evening meetings. Changes to the format and scheduling were agreed upon by the debaters. The eighteen days of debates were reported by the local Lexington press and even earned a brief piece in the New York Daily Tribune, November 27, 1843. The Democratic Standard of Brown County, Ohio, November 28, commented that, “Lexington is thronged at this time with spectators anxious to hear the debate.” By December 8, the Carroll Free Press of Carrollton, Ohio, informed its readers that two of the propositions for debate had been completed and “the interest which” the discussion “first awakened is not at all diminished….Large crowds are daily in attendance.” When the preliminaries of the debate were held in the Reformed Church in Lexington, the audience was said to be about two thousand. However, the press reported that the following meetings were in the Main Street Christian Church, which had just completed a new building with substantial seating and was the largest congregation in the city. It was surely a very different world for a regional debate on theology to capture the attention of listeners in other parts of the nation.

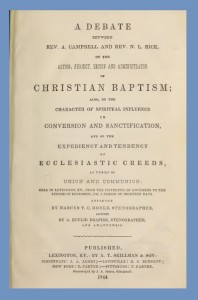

The debates were published with both Rice and Campbell editing the transcriptions and certifying their authenticity. The book was released in 1844 with the lengthy title, A Debate between Rev. A. Campbell and Rev. N. L. Rice on the Action, Subject, Design and Administrator of Christian Baptism, also, on the Character or Spiritual Influence in Conversion and Sanctification and on the Expediency and Tendency of Ecclesiastical Creeds, as terms of Union and Communion: Held in Lexington, Ky., from the Fifteenth of November to the Second of December, 1843, a Period of Eighteen Days. Reported by Marcus T. C. Gould, Stenographer, assisted By A. Euclid Drapier, Stenographer, and Amanuensis. The lengthy title must have been composed to correspond with the book’s 912 pages of small-font, narrow-margin text. The reviewers of the book in Princeton Seminary’s Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review, 1844, after a brief introduction to the context of the face off, listed the six points of debate agreed upon after considerable wrangling by Campbell. The first, baptism by immersion with the Trinitarian pronouncement is the only baptism; second, the infant of a believing parent is a scriptural subject for baptism; third, Christian baptism is for the remission of past sins; fourth, baptism is to be administered only by an ordained bishop or presbyter; fifth, in conversion and sanctification the Spirit of God operates on persons only through the word of truth; and sixth, human creeds as bonds of union are necessarily heretical and schismatic. Rice affirmed points 2 and 4; Campbell affirmed points 1, 3, 5, and 6. The review selects from the book excerpts from both men regarding translation of the New Testament Greek words bapto and baptizo. Campbell argued that the Greek must only and always be translated “immerse” and those through history that had not been immersed were in fact not baptized, to which Rice responded that baptizo and bapto must be translated according to context with meanings that include, “wash,” “pour,” “purify,” “sprinkle,” and “dip.” The review concluded that Rice’s response to Campbell was “so complete a refutation of the arguments usually adduced in favor of immersion as the only mode of baptism, [that] we cannot find a single position taken by Mr. Campbell which is not here completely wrested from him” (p. 593). Archibald Alexander and John Matthews are believed to be the reviewers. It does not appear that Alexander Campbell responded to Princeton Seminary’s analysis, but he would undoubtedly have disagreed.

The debates were published with both Rice and Campbell editing the transcriptions and certifying their authenticity. The book was released in 1844 with the lengthy title, A Debate between Rev. A. Campbell and Rev. N. L. Rice on the Action, Subject, Design and Administrator of Christian Baptism, also, on the Character or Spiritual Influence in Conversion and Sanctification and on the Expediency and Tendency of Ecclesiastical Creeds, as terms of Union and Communion: Held in Lexington, Ky., from the Fifteenth of November to the Second of December, 1843, a Period of Eighteen Days. Reported by Marcus T. C. Gould, Stenographer, assisted By A. Euclid Drapier, Stenographer, and Amanuensis. The lengthy title must have been composed to correspond with the book’s 912 pages of small-font, narrow-margin text. The reviewers of the book in Princeton Seminary’s Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review, 1844, after a brief introduction to the context of the face off, listed the six points of debate agreed upon after considerable wrangling by Campbell. The first, baptism by immersion with the Trinitarian pronouncement is the only baptism; second, the infant of a believing parent is a scriptural subject for baptism; third, Christian baptism is for the remission of past sins; fourth, baptism is to be administered only by an ordained bishop or presbyter; fifth, in conversion and sanctification the Spirit of God operates on persons only through the word of truth; and sixth, human creeds as bonds of union are necessarily heretical and schismatic. Rice affirmed points 2 and 4; Campbell affirmed points 1, 3, 5, and 6. The review selects from the book excerpts from both men regarding translation of the New Testament Greek words bapto and baptizo. Campbell argued that the Greek must only and always be translated “immerse” and those through history that had not been immersed were in fact not baptized, to which Rice responded that baptizo and bapto must be translated according to context with meanings that include, “wash,” “pour,” “purify,” “sprinkle,” and “dip.” The review concluded that Rice’s response to Campbell was “so complete a refutation of the arguments usually adduced in favor of immersion as the only mode of baptism, [that] we cannot find a single position taken by Mr. Campbell which is not here completely wrested from him” (p. 593). Archibald Alexander and John Matthews are believed to be the reviewers. It does not appear that Alexander Campbell responded to Princeton Seminary’s analysis, but he would undoubtedly have disagreed.

While N. L. Rice was across the Ohio River in Cincinnati overseeing the publication of the debates, he was offered a call to pastor the city’s Central Church. Accepting the opportunity, Rice returned home where he and Catherine gathered their family and possessions, left the blue grass, and settled in Ohio. He was installed in Central Presbyterian Church on January 12, 1845. During his ministry the congregation grew and became better established in the doctrines of the gospel. In addition to his pulpit and pastoral duties, he wrote several volumes, held more public debates, and taught classes of candidates that were preparing for the ministry. He also edited The Presbyterian of the West. After a fruitful ministry of eight years he would once again relocate the family for a new call.

Early in 1853, Rice moved due west over three-hundred miles to accept a call to the Second Presbyterian Church of St. Louis. He had been released from his pastoral charge in Cincinnati, April 9, 1853, and was installed in St. Louis on October 9. His pastorate in St. Louis was characterized by the same varied, incessant, and successful labors as his work in Cincinnati. In addition to his work as pastor and churchman, he edited The St. Louis Presbyterian and published several more books.

The next move was to Chicago which was a growing city as railroad service made it the hub of the midwest. Rice became pastor the North Church when he was installed by the Presbytery of Chicago, October 20, 1858. He found the congregation small and weak but with abundant opportunities for ministry in the city. Despite the work ahead of him with his congregation he once again took up editing with another serial, The Presbyterian Expositor. When the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Old School, (PCUSA) convened in Indianapolis on May 19, 1859, one of its major decisions regarded relocating the Theological Seminary of the Northwest. The seminary had already moved from its Hanover College campus and then another campus in New Albany, Indiana, because of shortages of funds, students, and facilities, so it was hoped that the next site would be the last. It was Rice who suggested Chicago for the new campus. Indianapolis was the other possible site but when the vote was taken, Chicago won by a margin of over three to one. Later in the assembly, Dr. Rice was elected the professor of didactic and polemic theology. In the fall, Rice’s professorship of theology would be named by action of the seminary board for Cyrus McCormick in honor of his “Christian munificence” expressed in his one-hundred-thousand dollar endowment of four professorships. Rice’s responsibilities had been greatly increased because he would continue as pastor of the North Church, a periodical editor, and teacher in the seminary.

Following his few years in Chicago, the Rices moved to New York. His new charge was Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church which had recently suffered the death of its beloved pastor, J. W. Alexander. The nearly seven-hundred-member congregation was only surpassed in size in the Synod of New York by Gardiner Spring’s Brick Church. Pastoral calls had already been turned down by Massachusetts-born W. G. T. Shedd and pastor of First Church, New Orleans, B. M. Palmer. A few weeks after Confederate forces fired on Union troops in Fort Sumter, Kentuckian Rice was installed on April 26, 1861. During his call in New York, Dr. Rice not only had to deal with the war between North and South, but he and Catherine had to experience cultural adjustment as they transitioned from the Midwest to life in Manhattan. Elder Henry W. Jessup, who authored the centennial celebration book for the church, said understatedly of Dr. Rice’s situation, “As a Southerner preaching in a New York pulpit during the Civil War, he occupied a very delicate position.” However, Jessup added that “by a discreet avoidance of all political topics, he maintained the affection and esteem of his people.”

Despite the positive review of Rice’s years by Jessup, the new call to the large urban congregation taxed the Kentuckian’s health greatly resulting in exhaustion from a busy schedule. After six years, N. L. Rice, following the suggestion of his physician, was released from his pastoral charge so he could move to a farm in New Jersey to convalesce. Despite the rural setting, his condition continued to weaken. In the winter of 1868, the Rices moved back to St. Louis where he could be treated by his son in law, Dr. E. S. Lemoine.

Renewed physically, N. L. Rice was offered the presidency of Westminster College which was a Presbyterian college in Fulton, Missouri. He initially declined the offer, but when pressed to acquiesce by the college board he accepted the position and began his duties in the fall of 1868. The school opened in 1851 and as with so many religious colleges, Westminster was having financial difficulties. Rice was seen to be a prominent father of the church who could strengthen the monetary situation and build an endowment while improving academics. The Synod of Missouri at its 1868 meeting expressed its concern that Westminster prepare college students for the ministry.

We are fully satisfied that our theological students should be trained, as far as possible, here on the field where they are to engage in labor. They will thus be kept in full sympathy with us and be the better acquainted with the character of the work they will be called to perform (p. 185).

This statement sounds like it would fit in with current thinking as seminaries, satellite campuses, and local ministers tailor candidates for local work—there is nothing new under the sun. The report to synod continued with its expression of hope in the leadership of Dr. Rice.

We believe that young men, expecting to become ambassadors of the Lord Jesus Christ, should receive some portion of their training from those who are actually engaged in the great work of the ministry.

The art of expounding God’s word with simplicity, and the peculiar tact that is required in pastoral visitations, can much more readily be acquired from successful pastors than from theological professors who have for years been withdrawn from the practical work of the ministry.

Note that last line which reads like it was written today with its emphasis on the importance of professors experienced in the “practical work of ministry” for teaching ministerial candidates. The importance of theological education and ministerial service were emphasized by Rice in his first address as Westminster College president when he delivered it to the Synod of Missouri with the title, “What Constitutes a Call to the Ministry?”

Westminster College’s financial situation continued to be troublesome during Rice’s years. By 1873, the faculty were complaining because they had not been paid for a year and they were fearful that the rumors of cutting their number or closing the college were true. Such information is quite disconcerting to employees, to say the least. The financial problems when Rice took office were severe, but despite the need to tighten purse strings he had hired additional faculty including one of his sons. Dr. Rice offered to have his own salary cut by twenty percent and then an additional ten percent if things did not improve the next year. The finances did not get better, so both of Rice’s salary cut offers were taken. He decided to leave the college resigning in a letter to the board, June 17, 1874. One of several factors working against Westminster College that was noted by Rice in his letter was competition for students from the Missouri state institutions “which possess the great attraction of educating free of all charge” and he added that every “denominational institution in the state is suffering from this cause” (p. 226). The son that Dr. Rice added to the faculty was John Jay Rice who was likely named for his uncle that had died on the mission field in Florida in 1840. It was a tense situation for both Rices when the college came to the point it might have to discharge some faculty to ensure survival of the school. However, John Jay Rice survived the storm having started his teaching in 1869 and he continued serving in one capacity or another until his death in 1920. He also served three terms as interim president.

Westminster College’s financial situation continued to be troublesome during Rice’s years. By 1873, the faculty were complaining because they had not been paid for a year and they were fearful that the rumors of cutting their number or closing the college were true. Such information is quite disconcerting to employees, to say the least. The financial problems when Rice took office were severe, but despite the need to tighten purse strings he had hired additional faculty including one of his sons. Dr. Rice offered to have his own salary cut by twenty percent and then an additional ten percent if things did not improve the next year. The finances did not get better, so both of Rice’s salary cut offers were taken. He decided to leave the college resigning in a letter to the board, June 17, 1874. One of several factors working against Westminster College that was noted by Rice in his letter was competition for students from the Missouri state institutions “which possess the great attraction of educating free of all charge” and he added that every “denominational institution in the state is suffering from this cause” (p. 226). The son that Dr. Rice added to the faculty was John Jay Rice who was likely named for his uncle that had died on the mission field in Florida in 1840. It was a tense situation for both Rices when the college came to the point it might have to discharge some faculty to ensure survival of the school. However, John Jay Rice survived the storm having started his teaching in 1869 and he continued serving in one capacity or another until his death in 1920. He also served three terms as interim president.

The next move of the household was in an easterly direction as Dr. Rice retuned to the village of his alma mater, Danville, Kentucky. He had been elected on June 17, 1874, to teach didactic and polemic theology in Danville Seminary. He accepted the position and was formally installed October 16, 1874, during the sessions of the Synod of Kentucky at Shelbyville. However, his time teaching seminary would be short. After the close of the session in May 1877, Dr. Rice travelled with his family to visit his brother-in-law in Bracken County. While there he grew seriously ill and passed away, June 11, 1877. His remains were taken to Fulton, Missouri, for burial. He was survived by Catherine and six of their seven children.

Dr. Rice was honored for his pastoral, educational, and connectional ministry during his nearly seventy years of life. In 1855 he was chosen moderator of the Old School General Assembly for the sessions held in Nashville, Tennessee. He was given the Doctor of Divinity by Jefferson College of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, in 1844, possibly as a result of his notoriety from the press coverage of his debates with Campbell and their publication. He also served on the Princeton Seminary Board of Directors, 1861-1869.

N. L. Rice not only edited the periodicals mentioned in this biography but also authored several books, lectures, and sermons, a few of which will be mentioned. The lengthy debates between Rice and Alexander Campbell are a challenging read, so if one wants to know Rice’s views apart from his interaction with Campbell it would be better to read Baptism: The Design, Mode, and Subjects, St. Louis: Keith & Woods, 1855. His book, Romanism not Christianity: A Series of Popular Lectures in which Popery and Protestantism are Contrasted; Showing the Incompatibility of the Former with Freedom and Free Institutions, New York: Mark H. Newman & Co., Publishers, 1848, contributed to the over-loaded shelf of antebellum literature written by Protestants against Roman Catholicism. Another topic of his day was social dancing which he addressed in A Discourse on Dancing, delivered in the Central Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, 1847; dancing was considered inappropriate for Christians because it was thought to lead to lust and sin. The abundant list of works on the Sabbath in nineteenth-century Christianity had a contribution from Rice titled, The Christian Sabbath: Its History, Authority, Duties, Benefits, and Civil Relations, 1863. One subject Rice addressed stepped a bit out of the ordinary, but it does address an issue of his era, Phrenology Examined, and Shown to be Inconsistent with the Principles of Physiology, Mental and Moral Science, and the Doctrines of Christianity. Also, an Examination of the Claims of Mesmerism, New York, Robert Carter & Brothers, 1849. Another theological work by Rice is his book, God Sovereign and Man Free: or The Doctrine of Divine Foreordination and Man’s Free Agency, Cincinnati: John D. Thorpe, 1851. Rice also published A Debate on the Doctrine of Universal Salvation: Held in Cincinnati…Between Rev. E. M. Pingree and Rev. N. L. Rice, D.D….[etc.], Cincinnati: J. A. James, 1845.

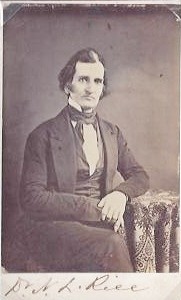

Barry Waugh

Sources Information on Rice and Westminster College is from, History of Westminster College, 1851-1903, from 1851-1887, by M. M. Fisher, and then continued to 1903 by John J. Rice (N. L. Rice’s son), Columbia: E. W. Stephens, 1906. The information on Rice’s son, John Jay Rice, is from his obituary in The New York Times, December 16, 1920. The Fifth Avenue Church book is, History of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, of New York City, New York, from 1808-1908, by Henry W. Jessup, 1909, which includes information about the centennial celebration, December 18-23, 1908. The CDV of Rice seated with his signature is the author’s. The image of Bible House of the New York Bible Society at Astor Place, Manhattan, is from McLaughlin’s New York Guide and Metropolitan Manual, 1875.

The editorial heading of the digital copy of the BRPR review of the Rice-Campbell book in the digital archives of Princeton Seminary cites the reviewers as Archibald Alexander and John Matthews. The agreed upon place for meeting was the “Reformed Church.” However, the press said the debate sessions took place in the Main Street Christian Church, which was, as was noted, a new and large building.

For those interested in some of the difficulties faced by McCormick funding the four professorships in the seminary and particularly the conflict with Willis Lord, see, Important Correspondence, Concerning the Presbyterian Theological Seminary of the North-West…etc., New York: A. C. Rogers, 1869, 94 pages. McCormick did not want Lord in the McCormick chair and neither man cared much for the other. N. L. Rice sided with McCormick. Also, there are biographies of Cyrus McCormick and J. W. Alexander on Presbyterians of the Past.

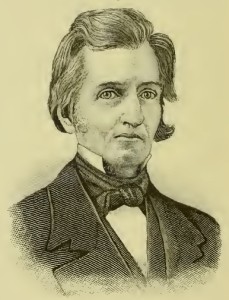

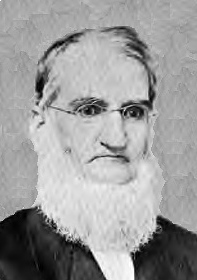

There is, at least was at the time of writing this article, a very nice picture of Dr. Rice on Find-A-Grave. He is standing with his hand inserted into his coat Napoleonesque—search “Nathan Lewis Rice, 1807-1877,” on the site. The picture is attributed to an album of graduates in Union Theological Seminary in New York, but it must have been taken during his years at Fifth Avenue Church when he may have lectured at UTS. He looks a bit like Liam Neeson in the picture, maybe?