George was born November 1, 1790, to Joseph and Eleanor Cochran Junkin on the family farm near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The spiritual ancestors of the Junkins were Covenanters who had entered the American colonies among the Scots-Irish. Eleanor Junkin was surely a busy mother because her fourteen children would have required every second of every day. Eleven of the ten sons and four daughters survived to marry and have their own families. One of his considerably younger brothers, David, would become known as D. X. Junkin and a minister like George. Joseph was a prosperous farmer as well as a successful entrepreneur who operated a mill, ferry service, and other businesses.

George was born November 1, 1790, to Joseph and Eleanor Cochran Junkin on the family farm near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The spiritual ancestors of the Junkins were Covenanters who had entered the American colonies among the Scots-Irish. Eleanor Junkin was surely a busy mother because her fourteen children would have required every second of every day. Eleven of the ten sons and four daughters survived to marry and have their own families. One of his considerably younger brothers, David, would become known as D. X. Junkin and a minister like George. Joseph was a prosperous farmer as well as a successful entrepreneur who operated a mill, ferry service, and other businesses.

George’s early education was received for several years from William Jamieson who was readily recognized in town because he walked with a crutch. The local children gathered for class in a log school house about a mile and a half from the Junkin home. Along the two longest walls of the cabin were log-high gaps above the students’ desks that allowed them to see outside and enjoy the Pennsylvania scenery as they labored over their books. In some cases in the era log school houses were used as miniature forts and the horizontal opening facilitated use of firearms. George said of his teacher that he was “a beautiful penman, a pretty good teacher, truly benevolent, and therefore greatly beloved.” Following Master Jamieson’s teaching he received further instruction from a succession of teachers—including one who prayed to close the school day only when he was drunk enough. George completed his studies and was hopeful that he could at some point go to college.

As he anticipated the possibility of further education, the family moved west about 250 miles from their Harrisburg area property to a more remote location on Hope Farm near Mercer. For three years George worked intermittently as a carpenter, jointer, farmer, sawyer, miller, and carder. He commented that on his family’s farm it was common that the harvesters drank whiskey as they cut and gathered the grain—keep in mind that the instrument for harvesting the crop was a razor-sharp scythe (see, “Notes” regarding the Whiskey Rebellion). After a few years, his interest in college studies induced him to discuss additional education with his father. Joseph was opinionated and was particularly against his son going to college. However, his mother interceded and convinced her husband that college would be good for their son, so George entered Jefferson College in Canonsburg, south of Pittsburgh, beginning his studies with a heavy dose of remedial Latin. He pressed on through the full curriculum, completed his examinations, and graduated in September 1813.

During George’s college years, he had professed his faith in Christ and came to believe that he was called to the ministry. The month after graduation he left home and headed east for New York to study in the Associate Reformed Seminary operated by John Mitchell Mason (1770-1829). He traveled on horseback crossing the Susquehanna River by ferry at Harrisburg, then proceeded to Lancaster where upon arrival he held an auction in the street to sell his horse and tack before taking the stagecoach to Philadelphia. When he arrived in Philadelphia he met a young man named John Knox—a good name for a Presbyterian seminarian—who was returning to Mason’s seminary for his second year. After a few days in Philadelphia, the students boarded a stagecoach headed for New Jersey and then the next day continued on to New York. The years in New York required some adjustments for George as he transitioned from western Pennsylvania home life to the challenges of living in the big city.

Having completed his divinity studies in 1816, George and three of his seminary colleagues set out in a wagon for ministry opportunities in western Pennsylvania. They arrived in Noblestown in Allegheny County for the meeting of the Associate Reformed Presbytery of Monongahela. He was examined for licensure and all his views were determined satisfactory except for one point regarding the Lord’s Supper—he did not hold to closed communion (only members in good standing of the particular church, presbytery, or synod may participate in the sacrament). The presbytery refused to license him to preach, so he asked if he could be licensed instead by the Big Spring Presbytery, which was also a presbytery of the Associate Reformed Synod. Instead of granting the request, Monongahela Presbytery reconsidered its decision and granted him a license. He delivered his first sermon in Butler, September 17, 1816. After several experiences testing his gifts for the ministry in various pulpits he was ordained an evangelist on June 29, 1818. He supplied the church in Newville briefly and was offered a call, but turned down the opportunity due to an inadequate salary and because many in the congregation, he thought, drank too much whiskey. While supplying the pulpit of the church in Milton, the church came to appreciate his ministry sufficiently to offer him a pastoral call which was accepted. During his Milton years he married Julia Rush Miller of Philadelphia, June 1, 1819. He not only shepherded his flock but was also involved in founding a local academy, publishing The Religious Farmer (1828-1829), and working with mission, Bible, education, and temperance societies. His participation in the temperance societies may have been motivated by problems in his congregation in particular and the area churches in general. He commented regarding the Milton Church.

Whiskey drinking was almost universal. A funeral even could not be conducted without the circulation of the bottle and the tumbler. Elders of the church deemed it not inconsistent with their Christian profession or their official position, to engage in the manufacture and sale of whiskey.

Pastor Junkin cared for his congregation and continued ministry in the Milton Church for eleven years before leaving pastoral ministry for educational service.

Junkin’s continued interest in and gifts for education resulted in his election in 1830 to the presidency of the Pennsylvania Manual Labor Academy. The school was located in Germantown which is currently considered a part of the city of Philadelphia. The position was accepted and in early August the Junkins moved to their new home. But his tenure was brief because he was elected to and accepted the presidency of Lafayette College in spring 1832. The trouble was, Lafayette College did not exist and was in the planning stages. The board was hopeful that Rev. Junkin had the ability to develop its vision for the college in Easton. Up for the challenge, he accepted the appointment, moved once again, and took with him the Pennsylvania Manual Labor Academy to become a part of the student body.

During his time of service to Lafayette College, Rev. Junkin became particularly concerned about doctrinal issues taking place in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA). While in Milton, he had left the Associate Reformed Synod to become a member of the Presbytery of Northumberland of the PCUSA, but since his move to Germantown he was a member of Second Presbytery of Philadelphia. Another member of his presbytery was the minister of First Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, Albert Barnes, who had published theological views that Junkin and others realized were contrary to the church standards. Joining others, Junkin brought charges against Barnes to presbytery but he was acquitted, but then on appeal to the synod he was found guilty and suspended from the ministry. The final appeal was to the PCUSA General Assembly which by a close vote reversed the decision of the synod and restored Barnes to ministerial duties. The assembly had concluded that the problem with Barnes’s teaching was a poor choice of words in his writings resulting in the impression that his teaching was unorthodox. Dr. Barnes was advised by the assembly to be more precise with his terminology. This decision was not well received by George Junkin nor some other members of the PCUSA, and the Barnes case became a key factor contributing to the division of the denomination into the Old and New Schools in 1837.

Having built Lafayette College from the ground up, President Junkin was then unanimously elected by the Board of Trustees of Miami University in Ohio, to become its next president in 1841 . The Miami trustees were particularly concerned that he should restore proper discipline and increase the quality of the curriculum. During his few years in Ohio, Junkin worked to fulfill the mandate of the board but meanwhile back at Lafayette some were gathering for a meeting with hopes of retuning him to the president’s office. During 1844, the same year he was moderator of the Old School General Assembly, Junkin was re-elected president of Lafayette and he retruned to Easton to begin in the fall. Under his administration the College steadily grew, but, as with so many of the educational institutions of the day, Lafayette continued to have difficulty raising sufficient funds to maintain its campus and improve its program.

Knowledge of Dr. Junkin’s gifts as an administrator had spread to other areas of the nation resulting in several schools seeking him for leadership. In 1848, Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, elected him for president. He accepted the new position, packed up the family in Easton and moved south to Virginia. As his work progressed the issues that would result in secession and the Civil War were developing. His family had grown to love Virginia but as the war neared he found himself torn between his political convictions and the situation that was developing. Two of his daughters had married professors in the Virginia Military Institute who were officers in the Lexington Presbyterian Church. Eleanor had married Deacon and Major Thomas J. Jackson in 1853, and then passed away with her infant child about a year later; the second daughter, Margaret, had married Elder and Colonel J. T. L. Preston. With the onset of war, Dr. Junkin, who was opposed to secession, reluctantly decided to relocate the family to the North.

George Junkin was over seventy years old when he packed up the family property to leave Lexington and head across the Mason-Dixon Line into Pennsylvania. He drove the family carriage through Williamsport and Hagerstown in Maryland, then on to Chambersburg. During the war and through his last years he continued to serve the church by supplying pulpits, supporting the temperance movement, and promoting Sabbath observance. George Junkin died of angina pectoris, May 20, 1868. The last sermon text he is known to have preached was John 14:1, “Let not your hearts be troubled. Believe in God; believe also in me.” His wife Julia had died February 23, 1854, from a protracted and painful illness. Julia and George had nine children. Rev. Junkin was honored with the Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) by Lafayette College in 1833, and then in 1856, Rutgers College honored him with the Doctor of Laws (LL. D.).

A few of Junkin’s several publications include An Address Delivered by Special Request Before the Theological Society in the Theological Seminary, Princeton, N. J, Philadelphia, 1833; A Treatise on Justification, Philadelphia, 1839; On Decision of Character: The Baccalaureate in Miami University, Rossville, 1844; Christianity, The Patron of Literature and Science, Philadelphia, 1849; An Apology for Collegiate Education: Being the Baccalaureate Address, Delivered on Commencement Day of Washington College, Lexington, 1851; The Baccalaureate Address, Delivered on Commencement Day of Washington College, Richmond, 1852; Civil Government an Ordinance of God: A Lecture for the Times, Philadelphia, 1861; A Treatise on Sanctification, Philadelphia, 1864; The Two Commissions: The Apostolical and the Evangelical, Philadelphia, 1864; The Tabernacle, Or the Gospel According to Moses, Philadelphia, 1865; and A Commentary Upon the Epistle to the Hebrews, Philadelphia, 1873.

Barry Waugh

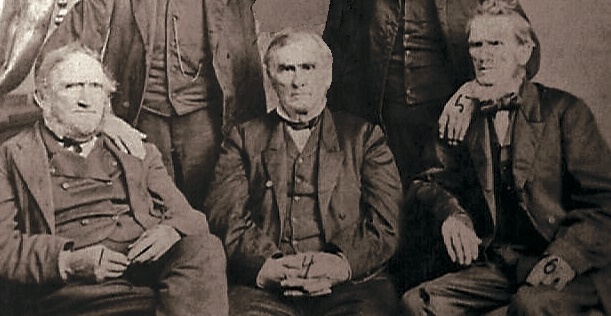

Notes—George Junkin is in the header photograph taken in 1865. To his right is Benjamin and to his left is William F. The picture from the PCA Historical Center is cropped from an image of six Junkin brothers at a reunion.

The Sam Houston Historic Schoolhouse in Maryville, Tennessee, is a log school house with horizontal windows like those in the school Junkin attended.

Whiskey Rebellion—In 1794, farmers in the western part of Pennsylvania were involved in the “Whiskey Rebellion.” The unrest began in 1791 when the yet young U. S. Congress passed an excise tax on spirits. Many frontier Pennsylvanians grew grain, much of which was distilled into whiskey. The western farmers could not successfully sell their crops as harvested because of the cost of and damage caused by shipping, thus whiskey and other spirits were more profitable and less bulky. It also seems, as George Junkin observed twenty-years later, there was a problem with the abuse of the liquid crop by the farmers themselves. Those involved in the Whiskey Rebellion believed the tax was another example of the eastern elite showing indifference to the needs of those on the frontier. President Washington issued an order in 1792 reaffirming the need to pay the tax, but trouble continued until violence erupted in Pittsburgh in 1794. Commander and Chief Washington led over 12,000 militia to suppress the unrest. It should be noted here that President Washington entered the distillery business himself in 1797 and by the time of his death in 1799 he was producing 11,000 gallons per year making him the largest distiller in the United States. The tax was not repealed until the presidency of Thomas Jefferson in 1802. Thus, President Washington enforced a national tax that he himself would have to pay when he went into the spirits business at Mt. Vernon. ( The informative website for Mt. Vernon was the source for most of this information.)

Another Presbyterian associated with Miami University and written about on Presbyterians of the Past is William H. McGuffey, 1800-1873.

When Eleanor Junkin Jackson died, Deacon T. J. Jackson considered marrying his deceased wife’s sister, Margaret, but decided against it due to the prohibition against such marriages in the Westminster Confession of Faith, 24:4, as a Presbyterian Church officer he had vowed to uphold and follow the confession.

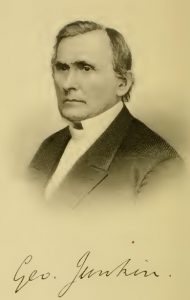

Sources—D. X. (David Xavier) Junkin wrote a lengthy biography titled, The Reverend George Junkin, D.D., LL.D., A Historical Biography, Philadelphia: J. B Lippincott & Company, 1871, provided the information for this biography, the portrait, the quote in the second paragraph is from page 30, and the one about whiskey in his congregation is on page 88. The other portrait and the sketch of the Lafayette College building were found in Nevin’s Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church, 1884, and it is not known to the author if the building existed at the time of Junkin’s presidency, nor if it still exists.