The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) requires those professing faith in Christ to affirm five vows indicative of their covenant with God and his Church (Book of Church Order 57:5). The vows acknowledge an individual’s sinfulness and need for God’s mercy, trust in the Son of God as savior from sin, purpose to live submitted to the Holy Spirit in obedience, concern to support the work of the church, and willingness to submit to the government of the Church. It may be thought that these vows date from the earliest days of Presbyterianism, but this is not the case. The article that follows provides a history of the development and use of vows in the branch of American Presbyterianism from which the PCA was established and it considers the context and influences creating an environment conducive to their adoption and use.

The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) requires those professing faith in Christ to affirm five vows indicative of their covenant with God and his Church (Book of Church Order 57:5). The vows acknowledge an individual’s sinfulness and need for God’s mercy, trust in the Son of God as savior from sin, purpose to live submitted to the Holy Spirit in obedience, concern to support the work of the church, and willingness to submit to the government of the Church. It may be thought that these vows date from the earliest days of Presbyterianism, but this is not the case. The article that follows provides a history of the development and use of vows in the branch of American Presbyterianism from which the PCA was established and it considers the context and influences creating an environment conducive to their adoption and use.

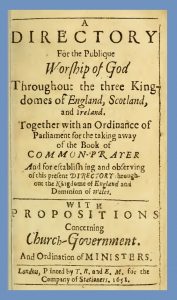

As Presbyterians increased in number in America and congregations were organized it became necessary to establish in 1706 the first presbytery which was named “The Presbytery.” The Presbytery provided a hub of connection for the many scattered churches so presbyters could deliberate common issues and provide collective leadership for their congregations. Continued growth and additional presbyteries led to formation in 1717 of “The Synod.” Twelve years later, The Synod subscribed to the Westminster Confession of Faith and its associated catechisms, however Westminster’s Directory for the Public Worship of God was not subscribed to, but it was instead recommended for use; it was “unanimously” judged “to be agreeable in substance to the Word of God” and “to all their members, to be by them observed as near as circumstances will allow, and Christian prudence direct” (Klett, 195). Westminster’s Directory did not include vows of membership.

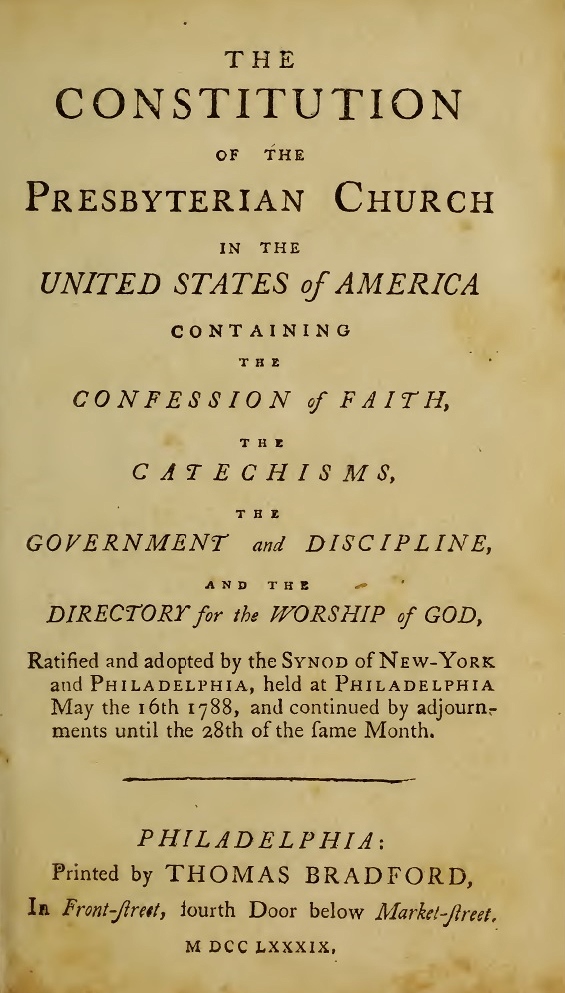

Fast forwarding six decades, American Presbyterians experienced sufficient growth to convene in 1789 the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA). That same year the first edition of the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church was published containing the Westminster Confession and catechisms, Form of the Government and Discipline, Forms of Process, and Directory for the Worship of God. The Directory published by the PCUSA is different from the directory composed by the Westminster Assembly, but the influence of Westminster can be seen in the organization, topics, and some portions of the text. The PCUSA Directory is more concise than Westminster’s, it includes paragraph enumeration, and it added a chapter on the singing of Psalms along with other changes. The following is the entire text of the 1789 chapter titled, “Of the Admission of Persons to Sealing-Ordinances,” which for twenty-first century readers means admission into communicant or church membership.

Sect. I. CHILDREN, born within the pale of the visible Church, and dedicated to God in baptism, are under the inspection and government of the Church; and are to be taught to read, and repeat the Catechism, the Apostles Creed, and the Lord’s prayer. They are to be taught to pray, to abhor sin, to fear God, and to obey the Lord Jesus Christ. And, when they come to years of discretion, if they be free from scandal, appear sober and steady, and to have sufficient knowledge to discern the Lord’s body, they ought to be informed, it is their duty, and their privilege, to come to the Lord’s Supper.

Sect. II. The years of discretion, in young Christians, cannot be precisely fixed. This must be left to the prudence of the Eldership. The officers of the church are the Judges of the qualifications of those to be admitted to sealing ordinances; and of the time when it is proper to admit young Christians to them.

Sect. III. Those, who are to be admitted to sealing ordinances, shall be examined, as to their knowledge and piety.

Sect. IV. When unbaptized persons apply for admission into the church, they shall, in ordinary cases, after giving satisfaction with respect to their knowledge and piety, make a public profession of their faith, in the presence of the congregation; and thereupon be baptized.

There is a distinction between admitting covenant children into communicant membership and admitting “unbaptized persons.” Presbyterians emphasized the responsibility of children to come to terms with their covenant baptism and grow in knowledge of the Lord sufficiently, as Section I expressed it quoting Scripture, “to discern the Lord’s body” (1 Cor. 11:29). The terminology used is that of the covenant child’s duty and responsibility to partake of the Lord’s body and blood in faith. That is to say, is the baptized child going to continue in the covenant, or is he or she going to become a covenant breaker. The “Eldership” determined the admissibility of the baptized to the Lord’s Supper, apparently without them coming before the congregation, but the unbaptized were to make their profession of faith before the congregation and then be baptized. No vows for becoming a communicant member of the church are included in the Directory for Worship in 1789.

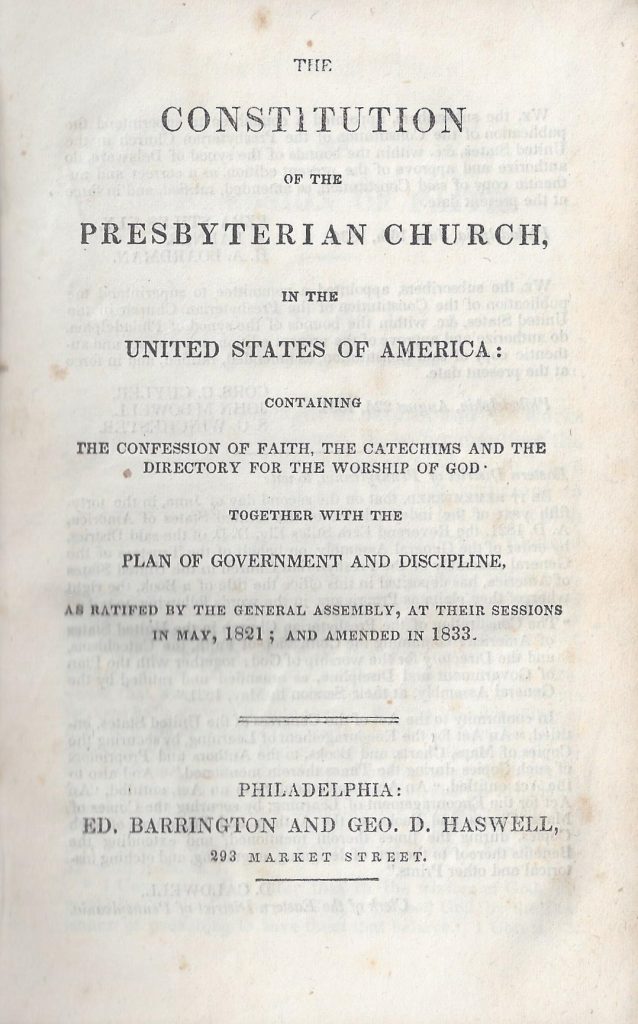

Nearly fifty years later, 1837, there was a major division of Presbyterians resulting in two Presbyterian Churches that were known popularly as the Old and New Schools. The Old School-New School division is important for the founding of the PCA because at the time of the division, the Presbyterians in the South were predominately Old School. An edition of the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church published just before the division, 1834, provided instruction concerning church membership but like the 1789 edition, it did not have membership vows.

In 1861, there was another division of Presbyterians as a result of the Civil War. The Old School churches in the Union through the Gardiner Spring Resolutions required allegiance of the PCUSA churches to the Union and their continued work to preserve the Union. This, the churches in the Confederacy could not do, so the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America (PCCSA) was formed. About half-way through the war, the PCCSA united with the southern New School Presbyterians to become one general assembly. Shortly thereafter a committee was appointed to revise the Old School Directory for Worship. The war ended in 1865 with the committee having not reported regarding the progress of their work. The PCCSA changed its name to the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS). Attempts to revise the Directory continued sporadically until 1879 when a new committee was appointed for the work. Despite good intentions, it took fourteen years to complete and adopt the finished Directory. The next year, 1894, the first edition of the Directory with membership vows was published, but it included only four of the five vows that would come to be used by the PCA.

The vow missing is the one regarding support of the church’s ministry and work, which reads, “Do you promise to support the Church in its worship and work to the best of your ability?” It was added to the PCUS Directory during an extensive revision of the Book of Church Order that was published in the edition of 1929, however, it was not added as the last vow but rather the fourth resulting in the relocation of the previous fourth to the fifth position. After thirty-five years, since the 1894 edition, the PCUS found it necessary to include a vow regarding church members supporting the ministry of the church, which raises the question, what prompted the revision?

In order to propose an answer to the question it is necessary to flip the calendar back to 1889. In the General Assembly of that year the PCUS instructed its members regarding participation in and giving to what are currently called parachurch or interdenominational organizations, which at the time were called voluntary associations or voluntary societies. A question arose at the assembly by way of a document from Concord Presbytery which the presbyters deliberated as Overture 10. The overture sought support for its position in a decision of the 1866 General Assembly that affirmed the “church in its organized capacity” is “God’s Bible and Missionary Society.” That is, the church organizes and directly oversees its ministries. The 1866 statement went on to encourage “every Church in carrying forward the work” of the American Bible Society because “its organization is simply for the printing and circulation of the Holy Scriptures.” On the one hand, the PCUS affirmed direct oversight of missions and ministries, but on the other hand, it provided an exception for the work of the American Bible Society. The PCUS was not excluding any and all association with parachurch organizations, but it was instead saying that a great degree of caution and consideration of a parachurch organization’s work must be exercised. The PCUS did not warehouse and distribute Bibles, but the denomination was interested in distribution of the Word of God. Returning to 1889 and Overture 10, its purpose was to call the church to oversee its own ministries. The overture had been composed in response to a decision of the 1888 General Assembly recommending “the formation of, wherever practicable, Men’s Missionary Associations, as also Women’s Missionary Associations (to be under the direction and control of the sessions), wherever they do not now exist.” Mention of “the control of sessions” appears consistent with the 1866 principle of church oversight, but as the Concord Presbytery overture unfolds further it becomes clear that this was not the case. The Missionary Associations were considered by the authors of Overture 10 to be parachurch organizations. These associations were to be approved by sessions for work within their congregations, but the sessions had no real control of their activities other than withdrawing their approvals or rebuking congregants for continued involvement. The Bills and Overtures Committee of 1889 made its recommendation concerning the overture, which was then adopted by the assembly.

Your Committee recommend that the Assembly, without expressing any opinion on the subject involved, send down this overture to the Presbyteries, with the direction that they patiently consider the whole subject of societies within and without the church, together with the subject of tithing as a means of raising the funds of the church, and return carefully formulated papers upon these points to the next Assembly.

How did the subject of tithing enter this recommendation? After all, the concern was participation in parachurch missionary societies. One point in Overture 10 stated that the Missionary Associations were functioning as “collecting agents” which if applied to other parachurch associations “would transfer this function to agents for all the benevolent objects which depend upon the offerings of God’s people.” The Missionary Associations were taking funds from the local church. The next year, 1890, the responses from the presbyteries were tallied. Note how many presbyteries were concerned enough about giving to the church to express their opinions regarding the tithe. Any judicatory would be delighted with a ninety-six percent response from its constituent courts within just short of a year.

In response to the overture of the last Assembly, sixty-eight Presbyteries of the seventy-one on the roll have sent up papers on the law of the tithe as a means of raising the funds of the church. All the shades of opinion expressed could not be presented without giving the papers in full, some of which are quite voluminous.

The following summary, however, is substantially correct:

Of the sixty-eight reporting, fifty-one express the opinion that the law of the tithe is not binding under the New Testament dispensation; ten regard it as still binding, either upon the church or the individual, or both; one is not clear enough to be put on either side; six decline to express an opinion.

Of the fifty-one that do not regard the law as binding under the present dispensation, sixteen refer to it as suggestive in the matter of systematic giving, or useful to guide the Christian in determining his duty.

Of the ten that believe the law to be binding, three advise against formal enactment or measures to enforce the law.

The larger number of Presbyteries enjoin greater consecration to the Lord, and liberal and systematic giving according to one’s ability; and quotes, as setting forth the Scripture principles that should guide in the discharge of this duty, such passages as these: “Let everyone lay by him in store as God hath prospered him”; “The Lord loveth a cheerful giver”; “As a man purposeth in his heart, so let him give.”

In 1890, the PCUS presbyteries were against, as the minutes say, “the law of the tithe,” but instead tended towards free-will offerings with some thinking the tithe could be a guide but not a requirement. Only ten of the sixty-eight presbytery reports expressed their support for the continued importance of tithing. It is really a remarkable statistic when considered from a twenty-first century perspective in that the PCA and its sister historically confessional Presbyterian and Reformed denominations generally believe in tithing as a fundamental principle of Christian living and an expression of gratitude to God for his grace.

As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth and then began its third decade, members of the PCUS still differed in their views regarding tithing, but things were changing. Some continued to believe tithing was legalistic while others thought it gave the believer a tangible tenth for guidance in giving, but a growing number of others thought the tithe was required as a beginning to even more generosity. The General Assembly said during its deliberations on the subject in 1924 that “the Church will more easily and quickly attain to the New Testament grace of sacrificial giving if it begins with the simple definite standard of the tithe.” So, the general opposition to or indifference regarding the tithe that was expressed in 1890 had changed over the years because the tithe came to be viewed as an archetypal portion for giving with the hope of giving even more. By 1933 all the intricacies of the final revised Book of Church Order including its Directory for Worship were resolved. When the PCA was formed forty years later it adopted the 1933 Book of Church Order as its own but not without several revisions over the next few years. The blue pencil of revision did not line out the fourth vow regarding support of the church, and in relation to vow four, the Directory, 54:1, provides some additional information regarding giving.

The Holy Scriptures teach that God is the owner of all persons and all things and that we are but stewards of both life and possessions; that God’s ownership and our stewardship should be acknowledged; that this acknowledgement should take the form, in part, of giving at least a tithe of our income and other offerings to the work of the Lord through the Church of Jesus Christ, thus worshipping the Lord with our possessions; and that the remainder should be used as becomes Christians.

Even though the tithe is not mentioned in vow four, chapter 54 provides an interpretation of giving to the church commensurate with the New Covenant. Where the law requires the tenth, the grace of the gospel shows the tithe to be a beginning. The fourth membership vow combined with the instruction given in chapter 54 well define the tithe not only as a tenth, but a tenth plus all God may provide for his cheerful givers to give. But the fourth vow is more encompassing than giving and the tithe when it says that members are to “support the church in its worship and work.” Sometimes when the vows are read and explained during the reception of members in a worship service, the minister limits the meaning of “support” to financial gifts. When a Christian supports the church, it includes participating in its ministry with time, talents, and skills. A tithe, or even a tithe plus, placed in the plate, bag, or box does not exhaust the meaning of “support.” As the Apostle Paul has said, the church is a body with each member fulfilling a necessary part of its life. So, when one professes faith in Christ or is received by transfer from another church and vows are administered, it is important to realize that supporting the church means being a disciple not only with dollars and cents, but also with time and talents. Vow four is a call to be involved in the work of the church because not only money, but also many hands, make light work of a congregation’s ministry.

In conclusion, the five membership vows used by the PCA were added to the Directory for Worship of the Book of Church Order by the PCUS in response to the growth of parachurch-interdenominational ministries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This has been shown in particular with the addition of vow four that requires a member to support the church. The case was not developed in this brief article, but it is believed that the four vows adopted in 1894 were intended to distinguish church membership in the PCUS as a shepherded, historic, confessional, and evangelistic church from the parachurch, revivalism, and interdenominational churches. Presbyterians believe God has ordained his church to be shepherded by elders according to the Word of God. The vows show not only the importance of believing in Christ but also the responsibility a believer has to be discipled by the church leadership. The goal of church leadership is encouraging members to be maturing disciples of Christ and faithful in worshipping God. The parachurch was not only drawing funds that should have been going to the PCUS churches, but it was also using church members in its work resulting in local congregations not having their parachurch-participant members available for full involvement in their own congregations. The issue was not only giving to the church with dollars, but also being in attendance for services and contributing time to the church’s ministry. In a connectional system like presbyterianism, the lost-time factor is particularly significant because presbyters work in graduated judicatories, that is, sessions, presbyteries, and general assemblies, all of which require participant attendance if they are to function. Even though the addition of vows to the Directory was a response to the parachurch trend affecting the PCUS, the continued use of vows by the PCA not only sets before the professing member the goodness of God’s grace and the duties of a disciple, but it also reminds the congregants witnessing the acceptance of members of their own vows and responsibilities. The parachurch can provide ministry opportunities and support services beneficial to the work of the PCA, but participation in the parachurch should be considered carefully remembering that the first responsibility of members as affirmed in their vows is congregational and connectional. Church ministry is spiritual and association with parachurch organizations by the PCA should result in supporting and not supplanting the denomination’s spiritual work.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The last part of the last paragraph was revised March 7, 2019. Information and quotes from the PCUS General Assembly minutes can be readily accessed online by going to the appropriate volume and reading its text or searching terms.

There was debate at the PCUS General Assembly in Louisville in 1912 regarding The Presbyterial Union and a brief report, authored by A. M. Fraser, is provided on pages 109-10 of Union Seminary Magazine, 23:2, December-January 1911-1912. The Presbyterial Union was a women’s organization.

The photograph of the filled church, courtesy of Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center, is the First General Assembly of the PCA. The image has been edited by the author of this site by removing some people walking down the aisle to leave the church. The meeting was held December 4-7, 1973 in Briarwood Presbyterian Church in Birmingham, Alabama, pastor at the time was Frank Barker Jr.

Klett refers to Guy S. Klett, Minutes of the Presbyterian Church in America, 1706-1788, published by the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, 1976. Some historians call the first presbytery “The General Presbytery” and the first synod, “The General Synod,” but the inclusion of “General” is not needed nor historically accurate. Klett’s edition of the minutes from 1706-1788 was transcribed from the original manuscript minutes which did not have “General,” see page viii for Klett’s comments regarding terminology.