When the Great War ended November 11, 1918, J. Gresham Machen’s work with the YMCA ceased but his return to Princeton was delayed because the troops were transported home first. He used the time to improve his French, travel the country, and attend lectures in universities. In a letter written in February 1919, he mentioned to his mother, Mary (Minnie) Gresham Machen, that he spent a night in Dijon and the city name reminded him of his grandparents’ home in Macon, Georgia, because it had the Gloire de Dijon Rose in the garden. The house can be seen in the header as it exists currently with two large magnolia trees flanking the entrance. The home was completed by Gresham in 1842 and is restored today as a bed and breakfast. However, the garden Machen remembered is no longer adorning the property.

When the Great War ended November 11, 1918, J. Gresham Machen’s work with the YMCA ceased but his return to Princeton was delayed because the troops were transported home first. He used the time to improve his French, travel the country, and attend lectures in universities. In a letter written in February 1919, he mentioned to his mother, Mary (Minnie) Gresham Machen, that he spent a night in Dijon and the city name reminded him of his grandparents’ home in Macon, Georgia, because it had the Gloire de Dijon Rose in the garden. The house can be seen in the header as it exists currently with two large magnolia trees flanking the entrance. The home was completed by Gresham in 1842 and is restored today as a bed and breakfast. However, the garden Machen remembered is no longer adorning the property.

John Jones was born January 21, 1812 in Burke County, Georgia, to Job and Mary (Jones) Gresham. He was raised in the country on his father’s farm near Brier Creek. His early education was aquired in local schools until he was fourteen when he attended an academy in Waynesboro, then another academy located at Richmond Baths. Gresham then joined the sophomore class of the University of Georgia in 1830. Gresham graduated with first honors. William T. Gould operated a law school in Augusta where Gresham studied before admission to the bar in Waynesboro in 1834. Gresham commenced practicing law but due to health concerns resulting from two bouts with fever he moved to Macon in 1836. After a brief partnership with Gen. Robert Beall that ended with his death, Gresham continued practice with Edward D. Tracy.

Gresham was first married to Miss Fiewellen sometime around 1839 but she lived only a few months, then on May 25, 1843, he married Mary Edgeworth Baxter who was the daughter of Thomas W. Baxter of Athens. She was described as “beautiful, refined, and cultivated.” They would have five children. Two children died in infancy; LeRoy Wiley would die in his teens; and Thomas and Minnie would mtaure to have families of their own. Practicing law provided a good income for Gresham resulting in his owning two plantations. He was elected the mayor of Macon for terms beginning in 1843 and 1847. However, by 1850, Gresham decided he had had enough of arguing cases in the courthouse, so he sought a new profession.

Manufacturing was on the rise in the nation particularly industries related to textile processing. Gresham joined Nathan C. Munroe, William B. Johnston, Thaddeus G. Holt, and others to open a large mill on Oglethorpe Street to process cotton and wool. The mill was incorporated the Macon Manufacturing Company by the General Assembly of Georgia in 1854. Two years later, Gresham and eight other investors incorporated the Warrenton and Macon Railroad Company to operate trains between the two towns. Thus, the railroad facilitated transportation of the goods produced by the Macon Manufadturing Company. Things were going well for Gresham, but events would soon take a turn for the worse.

In December 1861 Gresham joined other investors to establish the Georgia Mutual Insurance Company with capital stock including two-thousand shares at one-hundred dollars each. Notice the date, December 1861. The Civil War was in full swing with it looking as if the Confederacy could be victorious, however, as the war continued with the Confederacy defeated Gresham found himself financially strapped. He might have reconsidered entering the fire, marine, and life insurance business if he could have foreseen the way the war ended. Much destruction was wrought by Gen. William T. Sherman as he pressed his troops to take away the will and means for war from Southerners by destroying railroads, burning structures, and looting. Sherman would become acquainted with Gresham. The picture of a man upon his horse is Gresham. The story is the horse was stolen by Union soldiers. Gresham was enraged and wrote to Sherman demanding the return of his prize steed. The horse was returned and the photograph provides proof of Gresham’s victory over Sherman.

In December 1861 Gresham joined other investors to establish the Georgia Mutual Insurance Company with capital stock including two-thousand shares at one-hundred dollars each. Notice the date, December 1861. The Civil War was in full swing with it looking as if the Confederacy could be victorious, however, as the war continued with the Confederacy defeated Gresham found himself financially strapped. He might have reconsidered entering the fire, marine, and life insurance business if he could have foreseen the way the war ended. Much destruction was wrought by Gen. William T. Sherman as he pressed his troops to take away the will and means for war from Southerners by destroying railroads, burning structures, and looting. Sherman would become acquainted with Gresham. The picture of a man upon his horse is Gresham. The story is the horse was stolen by Union soldiers. Gresham was enraged and wrote to Sherman demanding the return of his prize steed. The horse was returned and the photograph provides proof of Gresham’s victory over Sherman.

Reticent to return to law even though he was a judge for a time after leaving his law practice, the uncertainties of Reconstruction contributed to his decision to return to law because it was a reliable source of income. His renewed practice was enhanced by taking on his son, Thomas Baxter Gresham, as a partner. The absence from law for several years had not improved his opinion of courtroom wrangling, so after a few years of renewed practice and increased frustration he retired to manage his investments and promote improved education.

Gresham knew that the future of the post-war South would depend on quality education, so he supported education not only financially but also with his time in various administrative capacities. In 1872, Gresham and other notables were appointed by the state to the Board of Education and Orphanages for Bibb County and he served for several years. The Board’s facilities included Bibb County Orphan Home, Macon Free School, and the school funded by the bequest of Elam Alexander named Alexander Free School. He was for a number of years the treasurer of the Macon Free School and at the time of his death was chairman of its board. He also was the president of the Alexander Free School for several years. The University of Georgia honored him with membership on its board for several years including a term as its president. He was also a trustee and treasurer of Oglethorpe University. The Central High School in Macon was renamed Gresham High School in honor of his many contributions to education.

Gresham knew that the future of the post-war South would depend on quality education, so he supported education not only financially but also with his time in various administrative capacities. In 1872, Gresham and other notables were appointed by the state to the Board of Education and Orphanages for Bibb County and he served for several years. The Board’s facilities included Bibb County Orphan Home, Macon Free School, and the school funded by the bequest of Elam Alexander named Alexander Free School. He was for a number of years the treasurer of the Macon Free School and at the time of his death was chairman of its board. He also was the president of the Alexander Free School for several years. The University of Georgia honored him with membership on its board for several years including a term as its president. He was also a trustee and treasurer of Oglethorpe University. The Central High School in Macon was renamed Gresham High School in honor of his many contributions to education.

The Greshams were members of First Presbyterian Church in Macon. Along with Judge Gresham’s vocational, educational, and legal interests, he was a churchman. He was elected an elder of First Church in 1847 and continued to serve until his death; for forty one of his years on the session he was the clerk. While visiting Philadelphia in 1854, he obtained the plans that were used to construct the current church building on Mulberry Street. When the building was completed in 1858, about one fifth of its cost had been paid by John and Mary Gresham. When the Second Presbyterian Church was built, the Greshams donated to the fund for its construciton. He was a member of the Board of Directors of Columbia Theological Seminary where he established the LeRoy Gresham Chair in memory of his son who died in 1865.

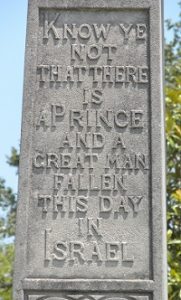

John Jones Gresham died in Baltimore at 9:00 the evening of Friday, October 16, 1891. Following a trip to Warm Springs in Bath County, Virginia, he went to Baltimore for an extended visit with his daughter Minnie’s family which included his grandson J. Gresham Machen. Judge Gresham’s remains were returned to Macon arriving on Monday evening. Following visitation in the family home his funeral service was led by Rev. W. B. Jennings of First Presbyterian Church who delivered a sermon from 2 Samuel 3:38, “Know ye not that there is a prince and a great man fallen this day in Israel?” The Board of Education honored its deceased member by attending the funeral, closing all the public schools for the day, and asking all teachers and students to attend the service then gather outside the church for a procession to the cemetery. Gresham High School, Second Presbyterian Church, and Alexander Free School were draped in mourning. Both the Southwestern Railroad and Central Georgia Bank honored their deceased director by closing for part of the day. The University of Georgia suspended classes at noon and at 3:00 the chapel bell called the professors and students to remember President of the Board of Trustees John J. Gresham. He is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery next to Mary who passed away in 1889.

The Macon Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) was in session when it received news of Judge Gresham’s death. The saddened presbyters responded by composing a brief letter of condolence to Thomas Gresham. From New Orleans, B. M. Palmer, pastor of First Church, also expressed his condolences to Thomas Gresham and other members of the family. An excerpt from one of Palmer’s letters shows the great loss he felt personally as well as the sadness of his colleagues.

The Macon Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) was in session when it received news of Judge Gresham’s death. The saddened presbyters responded by composing a brief letter of condolence to Thomas Gresham. From New Orleans, B. M. Palmer, pastor of First Church, also expressed his condolences to Thomas Gresham and other members of the family. An excerpt from one of Palmer’s letters shows the great loss he felt personally as well as the sadness of his colleagues.

The world can ill afford the loss of a single good man; and there are some so great as well as good that we cannot win our consent they should ever die. They seem so necessary to all the interests taken under their protection that we instinctively feel as though everything must fall to pieces without their presence and providential care. Hundreds of hearts through the State of Georgia were bowed under this sense of loss, when the tidings of your father’s death flashed over the wires. Not only in Macon but wherever he was known, the spontaneous cry was “A great man and a prince has fallen this day in Israel.”

On January 21, 1899, which would have been J. J. Gresham’s eighty-seventh birthday, his children Thomas and Minnie were present to honor their father at the dedication of the John J. Gresham building for the Macon Hospital Association. Minnie and Thomas had funded its construction to fulfill their father’s desire to have a facility available so the impoverished could be provided with healthcare. Minnie commented regarding her father’s opinion of money and its purpose that,

Money was with him a means for gratifying the innocent desires of his loved ones, and for the achievement of noble and beneficial purposes (Stonehouse, p. 13).

Barry Waugh

Notes–This article is a revision of “John Jones Gresham, 1812-1891” which was first posted August 9, 2017. The portrait, picture of Gresham on his horse, and the one of him rocking on his porch are copies used by permission of the 1842 Inn which currently occupies the Gresham home in Macon. The color picture of the inn and of the grave inscription for John Jones Gresham were taken by the author of this site. The letter Machen wrote to his mother is in Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I, Westminster Seminary Press & P&R, 2012, pp. 288-91. The primary sources include Testimonials to the Life and Character of John Jones Gresham, Baltimore, 1892, which is available at the Macon Library; the second source is Addresses Delivered at the Dedication of the John J. Gresham Building at Macon, Georgia, January 21st, 1899, Baltimore, 1899, which was kindly provided in PDF by Karla Grafton, Montgomery Library, Westminster Theological Seminary. Some biographical information is from, “Macon in Deep Mourning,” The Macon Telegraph, Sun, Oct 18, 1891, p. 2, and a lengthy account of his funeral is in “Funeral of J. J. Gresham, Most Imposing Ceremony Ever Seen in Macon,” The Macon Telegraph, Wed. Oct. 21, 1891, p. 6. Stonehouse refers to J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Memoir, by Ned B. Stonehouse, as published by the Committee for the Historian of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church; the pagination differs from other editions. Also used was D. G. Hart’s book, J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America; and Richard E. Burnett’s Machen’s Hope: The Transformation of a Modernist in the New Princeton. Some of the specifics regarding Gresham’s business and public service interests were obtained from Georgia Legislative Documents Online, which were accessed through the University of Pennsylvania site at, http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=galegacts.

LeRoy Gresham, 1871-1955, was Thomas B. and Lula Gresham’s son that was named for his uncle, LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1847-1865. LeRoy Wiley lived his brief life with considerable physical afflictions including injuries received at an early age. The Library of Congress has a multi-volume diary written by young LeRoy that spans several years of his life. He had an inquisitive and penetrating intellect that was borne by a frail and afflicted body.

J. G. Machen’s mother’s given name was “Mary,” and her mother’s name was “Mary,” thus it is likely that Machen’s mother’s nickname, “Minnie,” was used to avoid household confusion–possibly an endearing name given to her by her father.

The Second Presbyterian Church of Macon changed its name to Tattnall Square Presbyterian Church in 1892 according to James Stacy in A History of the Presbyterian Church in Georgia. Stacy also notes that it was first received by Macon Presbytery in 1887 but it appears the church was started in 1871. Possibly, it was a mission from 1871 to 1887,